Jews Not without Money

I was taken aback several years ago when my then teenage daughter casually mentioned how often fellow students at her upstate New York public high school told stupid jokes about Jews and money. Why do Jews have big noses? Because air is free. Why is it dangerous for a Jew to walk on the sidewalk? Because he’s always looking for pennies. She wasn’t shocked by these remarks, even when they came from classmates who knew she was Jewish and whom she considered friends. Maybe she assumed that such stereotypes are to be expected in an overcrowded school populated by different ethnic and religious groups daily negotiating an uneasy coexistence. But why didn’t I remember hearing “jokes” like these when I was growing up? Was it the difference between my relatively affluent, all-white, suburban Connecticut upbringing and the rough-and-tumble postindustrial town in which she was raised? Or had such anti-Semitic memes revived and intensified in recent decades? What does seem clear is that while stereotypes about Jews and money ebb and flow, they never truly disappear. Or, to borrow the potent (if gross) analogy employed by the historian Deborah Lipstadt, anti-Semitism is like herpes: Even when the blisters aren’t visible, the disease remains eternally latent beneath the surface.

Perhaps one reason for the tenacity of stereotypes about Jews and money is that Jews themselves find the subject of their historical relationship to it so painfully difficult to broach. Jewish defense organizations tend to denounce the stereotypes but rarely want to think about them, misleadingly insisting that Jews were for ages forced to survive through finance by a Christian society that wished to benefit from credit without suffering from the taint of usury. Jewish historians, when they haven’t affirmed this oversimplification, have tended just to ignore economic history. Many scholars appear to be themselves embarrassed by the association of Jews and commerce, which they know is not without historical foundation but aren’t quite certain how to explain. What is necessary rather is to demythologize the topic, to puncture its mystique, and to thereby reduce its power to shock, titillate, and offend.

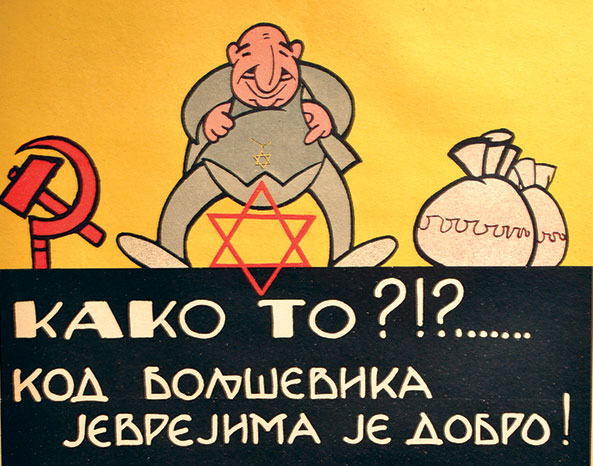

Precisely this is the signal achievement of the current exhibit Jews, Money, Myth at the London Jewish Museum. It debunks some of the most potent libels about Jewish financial power while also giving serious attention to the important roles that money in its various functions—in business, halakha, and philanthropy—has played in Jewish life. In short, Jews, Money, Myth normalizes the Jewish relationship with money without negating those factors that made this particular historical association especially fraught. Impressively, this feat is achieved with—forgive the pun—great economy (the full experience is under two hours), visual splendor (beautiful ritual objects and artwork), and even the occasional joke (and not just the anti-Semitic kind).

I visited the exhibit on a humid June day, when the museum’s air conditioning system had apparently malfunctioned, causing beads of sweat to dribble down and smudge my notes into indecipherability. The raucous voices of a troop of young school children touring the site—one wonders what they made of it all—clashed with the repeating loops of videotaped talking heads explaining the history of Jews and commerce, the evolution of anti-Jewish motifs in medieval art, and so on. Yet the heat and cacophony hardly diminished my absorption in Jews, Money, Myth, which tells the concurrent stories of Christian economic anti-Semitism and actual Jewish livelihoods from the Middle Ages through the present, especially in England.

The show is particularly resonant in London now because of widespread Anglo-Jewish anxiety over a resurgent British anti-Semitism, especially from elements within Jeremy Corbyn’s Labour Party. To take one early, apposite example, in 2012 a mural depicting stereotypical Jewish-faced bankers seated at a Monopoly board propped on the backs of dark, suffering slave-like figures was removed by the local London town council as blatantly anti-Semitic. Corbyn’s initial reaction was to tell the artist that he was actually “in good company” since Nelson Rockefeller had once had a mural by the great Mexican painter Diego Rivera destroyed because he objected to its favorable depiction of Lenin.

Jews, Money, Myth opens, logically if undramatically, with a section on money and numismatics in biblical and later Jewish law and ritual. This leads to one of the show’s few missteps because it feeds the false impression that stereotypes about Jews as moneybags have ancient origins, though they really date from the Middle Ages. Even one or two of the contributors to the otherwise excellent exhibit catalog (which is more of a companion volume of short essays by leading scholars) employ the clichéd term “2000 years,” as if economic anti-Judaism is to be found at the very birth of Christianity.

Thus the historian Sara Lipton, in her catalog chapter “Jewish Money and the Jewish Body in Medieval Iconography,” asserts that,

Christian texts had long associated Jews with wealth and worldliness, from Christ’s ejection of the moneychangers from the Temple forecourt to Paul’s equation of Jewish literalistic reading of Scripture with materialism, to the late fourth-century sermons of John Chrysostom, the Archbishop of Constantinople, who accused the Jews of luxury and ostentation.

But, as recent New Testament scholarship has amply demonstrated, the Gospels and the Epistles of Paul cannot simply be described in their original historical context as “Christian” texts. Virtually all of the figures depicted in the Gospels, including of course Jesus, are Jews. The Temple moneychangers were thus not a symbol for all Jews in the eyes of the early church, nor did Judas’s betrayal of Jesus for 30 silver pieces become a prototype of Jewish greed until the Middle Ages, as Lipton herself later acknowledges. The Augustinian (more than Pauline) charge of Jewish materialism was directed at the way Jews read the Old Testament, not how they earned and spent. It was about their stubborn failure to accept the allegorical or spiritual reading of the text that saw Jesus everywhere prefigured. Early Christians, as well as pagan Greeks and Romans, said all kinds of nasty things about Jews, including that they were beggars, layabouts, and knaves, but the stereotype of the so-called money Jew, came much later. The Gospel images of the Temple moneychangers and an avaricious Judas were retroactively deployed to reinforce that stereotype only after it had already come into existence in the Middle Ages.

There is no ancient calumny regarding Jews and money because Jews had no distinctive occupational identity before the Middle Ages, either under the crescent or the cross. Exactly when, why, and how most Jews ceased to be peasants like their Muslim and Christian peers and became mostly city dwellers instead remains a long-debated question among historians. When Jews did move to the cities, some of them eventually became moneylenders, but many others were peddlers, traders, artisans, and household servants. Both the exhibit itself and the catalog contribution of historian Julie Mell show that the majority of Jews in Christian lands were not moneylenders—and exceedingly few were rich.

As Mell argues, moreover, Jews were never—I would prefer to say rarely—as economically important or uniquely “functional” for the medieval economy as their enemies or even their friends made them out to be. Had it been left to the Jews alone to spread credit and commerce throughout the West, it might still be a backwater. Nevertheless, Jews were disproportionately involved in finance, trade, and business in Europe as well as large parts of the Islamic world. While Jewish preeminence in commerce has been grossly exaggerated, so too then has the notion that Jews were initially pushed into commerce and finance by Christian anti-Jewish policies.

Jews, Money, Myth must tell a story, so it can only hint at such complexity and historical uncertainty. The exhibit exposes some dangerous myths but also pays tribute to the reality of Jewish participation in the history of business and credit. One section focuses on the role of early modern Sephardi financiers in the history of English business life, such as the grandees Daniel and Sarah Judith de Castro. But it also powerfully juxtaposes their opulence with vivid illustrations of the far larger numbers of hard-pressed hawkers, peddlers, and old-clothes men who barely eked out a living. A number of hawkers’ licenses from the 18th century indicate the extraordinary degree of regulation imposed on those early traveling salesmen, precluding their use of vehicles and beasts of burden, while sharply delimiting the territory they were allowed to cover. Some of the caricatures of Jewish peddlers and merchants seem benign, a few are even amusing, but many are clearly malevolent. One shows the worshipers at the Great Synagogue of London giving thanks to the Almighty for steering a large Gentile loan into their hands.

Similarly, the depictions of the Rothschilds can only be described as grotesque, showing how, by the 19th century, conspiratorial notions of Jewish financial manipulation reached monstrous proportions—with ultimately fatal consequences for European Jews. The power of the myth here overwhelms even the at times impressive reality of Jewish commercial accomplishment. What’s so striking is the degree to which this exhibit manages to convey both.

Of course, any exhibit this ambitious is bound on occasion to stumble. A loose, Egon Schielesque pictorial rendering of Shakespeare’s Merchant of Venice by the Israeli artist Roee Rosen deliberately but inexplicably conflates Shakespeare’s nuanced, half-sympathetic Shylock with Christopher Marlowe’s unambiguous archvillain Barabbas. A film short by the artist-comedian Doug Fishbone rehearses all of the historical clichés surrounding the history of Jews and money while reinforcing their corresponding apologetic evasions, almost haplessly undoing all of the exhibit’s previous good work. Fishbone even manages to mangle the punchline to a well-known joke—the one about the schlemiel getting measured for a new suit—that might itself be 2,000 years old.

Finally, the exhibit’s closing video sequence serves a mashup of current manifestations of the Jews and money canard, including excerpts of American Evangelicals shouting hosannas to Jewish business acumen alongside Brexit campaign ads plastering ominous images of the Jewish punim of liberal financier George Soros (the Shylock/Barabbas of our day) across the big screen. While some of these clips are truly jaw dropping, others, like a snippet from Sacha Baron Cohen’s 2006 Borat, are merely uproarious. The problem is that the exhibit fails here to make any clear distinction between economic anti-Semitism and the satirizing of it.

But perhaps the curators deliberately sought by such means to underscore the murky nature of their subject, trapped in the indeterminate space between representation and reality. As David Feldman, the exhibit’s lead historian and the director of the Pears Institute for the Study of Antisemitism at the University of London, writes in his concluding essay to the catalog:

Jews make up 19 percent of the world’s wealthiest [people] . . . In Britain today, Jews are the religious group least likely to be poor (which is not to say, of course, that there are no poor Jews). Here is a remarkable phenomenon in need of an explanation—but one that no longer resorts to stereotype and caricature.

If Jews, Money, Myth helps spur investigation into this “remarkable phenomenon,” not only old myths but enduring historical mysteries may yet get cleared up.

Suggested Reading

Early Modern Blasphemy and Postmodern Virtue

Was Jacob Frank a progressive trendsetter or a seductive cult leader?

Life with S’chug

Einat Admony, who was raised by an Iraqi mother and a Persian father in Bnei Brak and now runs gourmet Middle Eastern fusion restaurants, is a new wave balaboosta.

The Rise of Hank Greenberg

On Rosh Hashana, Greenberg went to shul, then the ballpark and hit two home runs. "Hank’s Homers are strictly Kosher," said the Detroit Free Press.

Distant Cousins

None of these four novels by American Jewish writers is fully at home in Israel—they’re more like Mars orbiters than rovers.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In