A Different Kind of Hero

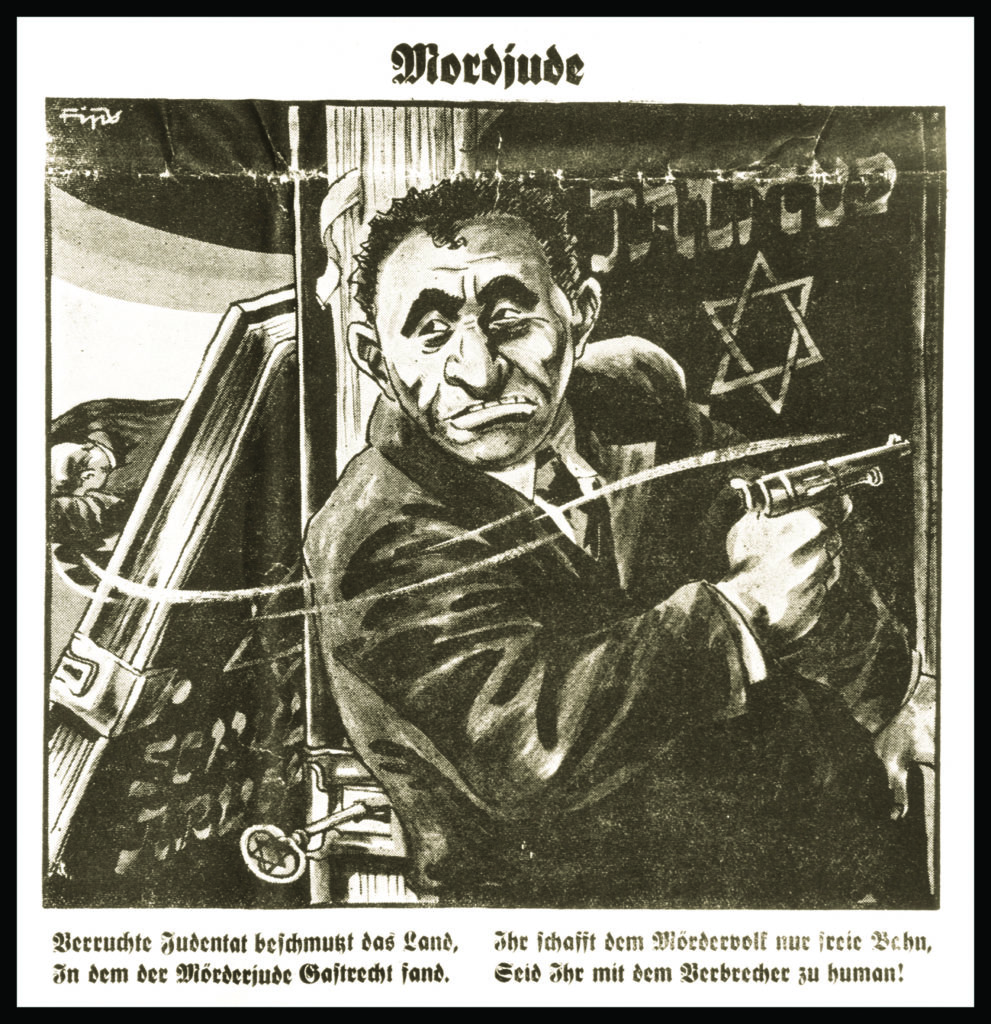

On November 7, 1938, a 17-year-old Jewish boy named Herschel Grynszpan, distraught over the Nazi persecution of his family and thousands of other Polish German Jews, slipped into the German Embassy in Paris and used a gun he’d never fired before to shoot the first diplomat he saw. When the diplomat died two days later from the wounds, Adolf Hitler and his sinister propaganda henchman, Joseph Goebbels, changed the course of history by turning this one rash act of one Jewish teenager into a pretext for the Kristallnacht, the nationwide orgy of mass state-sponsored anti-Semitic criminality, violence, and murder that initiated the Holocaust. Scholarly accounts of the Kristallnacht, the Holocaust, and the Second World War ordinarily devote a few lines—sometimes even a couple of paragraphs—to Herschel’s story, noting how the Nazis exploited his brave but foolish “protest” to ignite the great pogrom.

In 1938, Europe was on the cusp of a political transformation. Western Europe’s worst fear—and it was a truly terrible fear—was the threat of another world war. After the murderous horrors of the first one, a second, even worse one loomed as madness that could kill millions, bringing the end of civilization. Europeans high and low went into deep denial, desperately convincing themselves that Hitler was somehow a normal, if distasteful, politician who could be handled and appeased. The Munich pact, long since a byword for diplomatic cowardice and disgrace, had been signed a mere month before the Kristallnacht, and for one fleeting month, the pact had been celebrated with delirious mass relief. Apart from Jews and others who had taken Hitler’s measure, the Munich Agreement was greeted by euphoric waves of joyful people—people by the hundreds of thousands literally dancing in the streets.

With the Kristallnacht, that dancing stopped. On November 9–10, when Hitler ripped off his mask of legitimacy and normality to reveal the true face of his fundamentally criminal regime, the pipe dream of a rational, appeasable Hitler died a swift, sickening death. Plenty of appeasers kept busy, but for most, the truth was clear: Hitler would stop at nothing. The fearsome return of war was probable, unavoidable, even inevitable.

But there is more to Herschel’s story. When I stumbled onto it and began to dig, I discovered that his place in history extends well beyond the horrors of November 9–10, 1938, and reaches into the Holocaust itself.

Hitler had plans for Herschel that went well beyond being the pretext for the pogrom. He wanted to make Herschel a significant actor in not one but two momentous events. The second event, though monstrous, is much less well known because it never took place, and it never took place because of the strange, brilliant heroism of Herschel Grynszpan.

When France fell in 1940, the dictator sent an elite squad of the Gestapo to find Herschel Grynszpan, arrest him, and bring him to Berlin alive.

Why alive? Because Hitler had decided to turn the boy into the defendant in a major media show trial in Berlin, “proving” that the Second World War had been started by the “World Jewish Conspiracy,” using the “evil” Herschel as their trigger. Herschel would stand in the dock while a roster of the most notable anti-Semites in Europe mounted the witness stand, swearing to the solemn historical truth of this preposterous lie, pointing to the young man’s role in it. Enormous amounts of Nazi money, time, and energy went into planning this charade. Hitler was kept constantly informed. The star witness was to be no less than former French foreign minister Georges Bonnet, a covert Nazi fellow-traveler and major player in Munich, who promised the Nazis to tell the world that, yes, indeed, France went to war in 1939 only because of relentless, irresistible, warmongering pressure from “the Jews.”

But Hitler’s anti-Semitic spectacle had an even darker purpose. He wanted to make the extravaganza into worldwide news to be used as cover for the coming Holocaust. The trial was initially timed to coincide with the Wannsee Conference, when the mass murder of the Jews became settled Nazi policy. But it never took place.

It never took place because Herschel Grynszpan kept it from taking place. As a prisoner of the Nazis, Herschel had quickly grasped that he was being primed for more anti-Semitic propaganda. To prevent that disgrace, he concocted an extraordinarily ingenious lie. He claimed that he had not really killed the German diplomat for any political reason at all. His “protest” had merely been his cover for a deeper secret: the unspeakable truth that he’d killed the diplomat in the midst of a homosexual lover’s quarrel.

Nazi homosexuality? A decadent affair with a teenager?! This inspired falsehood was certain to turn into the trial’s most scandalous news story. It made an enraged Goebbels advise Hitler to postpone the whole thing. It stayed postponed forever. Herschel’s story is now almost forgotten, but it has a tragic and heroic side. When he assassinated that German diplomat, Herschel Grynszpan was still really a child: He was brave, sympathetic, and foolish, but a child. When he invented the lie that stymied Hitler’s propaganda cover for the Holocaust, he had grown. He had become a man. He was still brave, still bright, but he was a man who knew that his life was over. He would never leave Nazi captivity alive. Facing that inescapable fate, he decided to fight, using the only weapon he had—himself—and die that death for his people.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

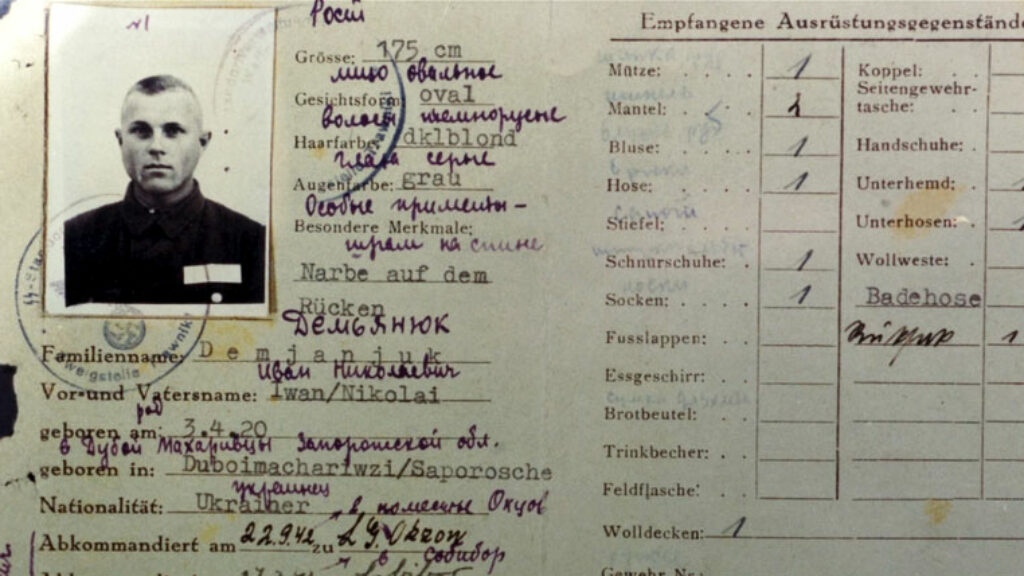

Ivan the Terrible?

A new miniseries from Netflix manages to maintain the tension of the long-decided, if not entirely resolved, case of John Demjanjuk.

Letters, Fall 2020

The Coffee a Good Schmooze Demands, Unjustified Resentment, Whose True Voice?, and Yesterday's Today

Responses to Halkin

Hillel Halkin's article about the future of Israel and Zionism has sparked a tremendous debate. We have curated some of the most interesting and engaging responses.

Conservative Judaism Is Too Important to Fail

Susan Grossman acknowledges the movement’s failings, but sees more reason for hope than despair.

S.J.D. Schwartzstein

But there is also the possibility that there was actually some sort of homosexual relationship, as vom Rath was known in Paris as "notre dame de Paris."

Gary

British composer Michael Tippett was inspired by Grynszpan's actions to write an oratorio A Child of Our Time, written between 1939-1941. He modeled it after the Bach Passions, using African-American spirituals in place of the Lutheran chorales. There are several performances available on YouTube.