Punctuality, Mendelssohn, and Nihilism: Remembering Alexander Altmann

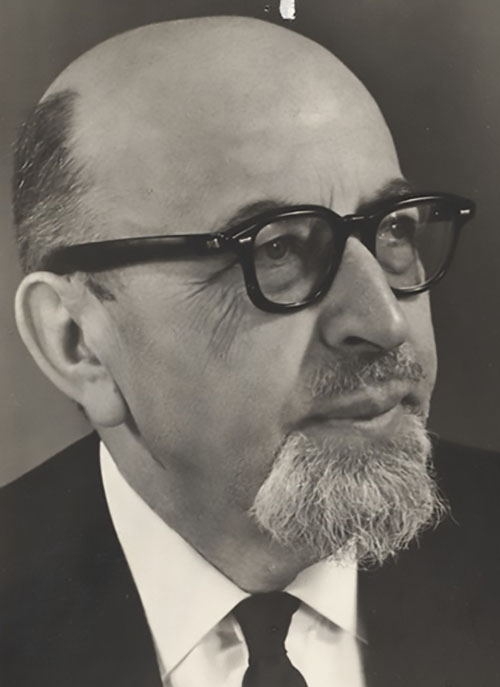

In 1980, I met with the great Mendelssohn scholar Alexander Altmann to discuss Moses Mendelssohn’s Jerusalem several times before he asked me to translate it for the new edition that he planned to produce. When I went to see him at his house in Newton Centre, Massachusetts, not far from where I lived, I always took care to be as prompt as possible. It seemed like one of the requirements of working with a yekke, the kind of Central European Jew who wore a jacket and tie even if he had no plans to leave the house. I soon learned that I wasn’t wrong—not from him but from his wife, Judith. One day I parked around the corner from the Altmanns’ home, sat in the car for a little while because I was early for our appointment, and then went to the door and rang the bell at precisely 2:00 p.m. “Ah, Mr. Arkush,” Mrs. Altmann cheerfully remarked as she opened the door for me. “Always on time!”

In January 1981, Professor Altmann, who was then a professor emeritus at Brandeis University, scheduled a meeting concerning the publication of Jerusalem with a representative of the University Press of New England and David Steinberg, then a vice president of Brandeis (and a son of Rabbi Milton Steinberg, author of the classic historical novel As A Driven Leaf). I had an early lunch on campus and then stationed myself in a hallway in Ford Hall (no longer standing), directly across from the Administration Building, and waited there until 12:59 p.m. That left me one minute to get to Steinberg’s office at 1:00 p.m. When I entered the office, maybe a few seconds early, the first person I saw was Mrs. Altmann, who looked up to me from her seat in the waiting room, smiling appreciatively for obvious reasons. When Professor Altmann, who was pacing the waiting room, took note of me, he just said, “It’s at 7 o’clock.”

He wasn’t telling me—as I understood immediately—that we would have to spend the next six hours waiting for the others. Something else was on his mind. A few days earlier, he had invited me to the Seder at his house but hadn’t been able to tell me when to arrive. Perhaps because the event was still months away, he hadn’t called me back to fill in the missing detail. But the matter had clearly weighed on him, and once he saw me, he needed to get it off his chest immediately.

Telling me when to come didn’t begin to put him at ease, though. Because it was already 1:01 p.m., and the others weren’t there! Fortunately, however, before another minute passed, Steinberg and the man from UPNE, whose name I can’t remember, hurriedly entered the room. Steinberg was all apologies, saying something about how he knew how important it was to Professor Altmann to be on schedule. I expected that Altmann, a man of infinite politeness, would reassure him that he had really been punctual enough, that no harm had been done. Instead, he looked at Steinberg, not coldly but without any warmth, and said, “Mr. Arkush was also on time.”

That was a very uncharacteristic rebuke, quiet as it was. I knew and worked with Professor Altmann for a number of years, and I can recall no other such incident. I was not able to trail after him like the youth Moses Mendelssohn describes in Jerusalem, who could “follow an older and wiser man at his every step, to observe his minutest actions and doings with childlike attentiveness . . . inquire after the spirit and the purpose of those doings and to seek the instruction which his master considered him capable of absorbing and prepared to receive.” But I got to see a lot. I’ll never forget the moment, for instance, that I ran into him in the basement of Harvard’s Widener Library. As we chatted, a rather spacey stranger joined our conversation, cheerfully interjecting non sequiturs. Professor Altmann didn’t suffer this fool gladly, but he quickly sized him up as harmless and responded to him with bemused cordiality—as he continued to talk to me—until he went away.

Alexander Altmann has been gone a long time now, more than 30 years. But he lives on in his books, some of which I consult with regularity—whether to refresh my memory of his ideas or just to touch base once again with his unfailing eloquence, in both his native language and his adopted one. The other day I took The Meaning of Jewish Existence: Theological Essays 1930–1939, a book published four years after his death, off my shelf.

It was a humbling experience. When Altmann wrote these essays, he was younger than I had been when I translated Jerusalem. But not then and, I’m afraid I have to admit, not even today could I pretend to possess anything remotely like his mastery of Jewish sources and contemporary philosophy. My friends and I often lament the lack of cultural literacy of many of the students who show up in our university classrooms. But the gap between them and what we were like at their age is surely smaller than the one that separated our younger selves from even the run-of-the-mill yeshivah and gymnasium graduates who showed up in German universities in the early 20th century—let alone a figure like the young Alexander Altmann, who never stopped learning.

One thing that struck me as I reread The Meaning of Jewish Existence was the near absence of Moses Mendelssohn from the volume. It wasn’t, in fact, until after World War II that Altmann began to devote his immense energies to researching the historical figure about whom he published voluminously and with whom his name is now most closely associated. Remembering this, I couldn’t help but recall the shloshim commemoration held for Professor Altmann in July 1987 at Brandeis University, a month after his death.

One of the eulogists was his longtime colleague in the Department of Near Eastern and Judaic Studies, Nahum Glatzer, another legendary yekke of vast erudition. Glatzer, I recall, sadly described Altmann’s vast expertise in a large variety of fields as well as his extensive writings on medieval Jewish philosophy and Jewish mysticism. But, he noted, he had devoted what seemed to be an inordinate amount of time to one individual. “The question we must ask,” Glatzer concluded, “is why Mendelssohn?” And then he stopped. For a painfully long minute, the then 84-year-old Glatzer stood staring at the audience of perhaps two hundred people, frozen.

Eventually, the organizer of the event, Paul Mendes-Flohr, a close student of both Altmann and Glatzer, came to the podium and gently escorted Glatzer away—leaving the question hanging. I tried to answer it myself, later that year, in a session in Altmann’s memory at the annual conference of the Association for Jewish Studies. I didn’t have The Meaning of Jewish Existence at my disposal when I did so, but if I had, it would have helped at least in one respect. In an illuminating introduction to the essays, Mendes-Flohr describes how beset young Alexander Altmann had been by “the emergence of an ominous nihilism” in the years after World War I and how much his own early philosophical efforts constituted an attempt to combat it.

It seems that in the aftermath of the next world war, Altmann took a different tack in his battle against nihilism. He devoted himself to the intense study of a pioneering modern Jewish thinker who had lived a noble life, a man whose unshaken confidence in the existence of God, providence, and immortality could continue to inspire us, if not necessarily convince us that the philosophy to which he adhered was a true one. I remain grateful for the small part that Alexander Altmann assigned to me in his great Mendelssohn project. And I think that both he and Mrs. Altmann would be pleased to know that I’m still always on time for everything.

Suggested Reading

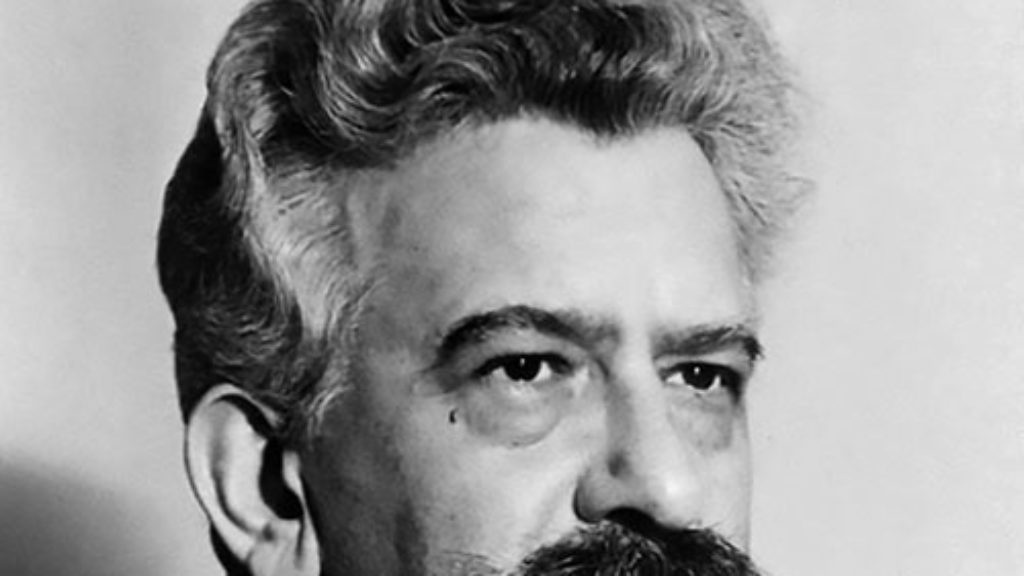

Prague Summer: The Altneuschul, Pan Am, and Herbert Marcuse

A mysterious memoir of planes, Marx, and minyans.

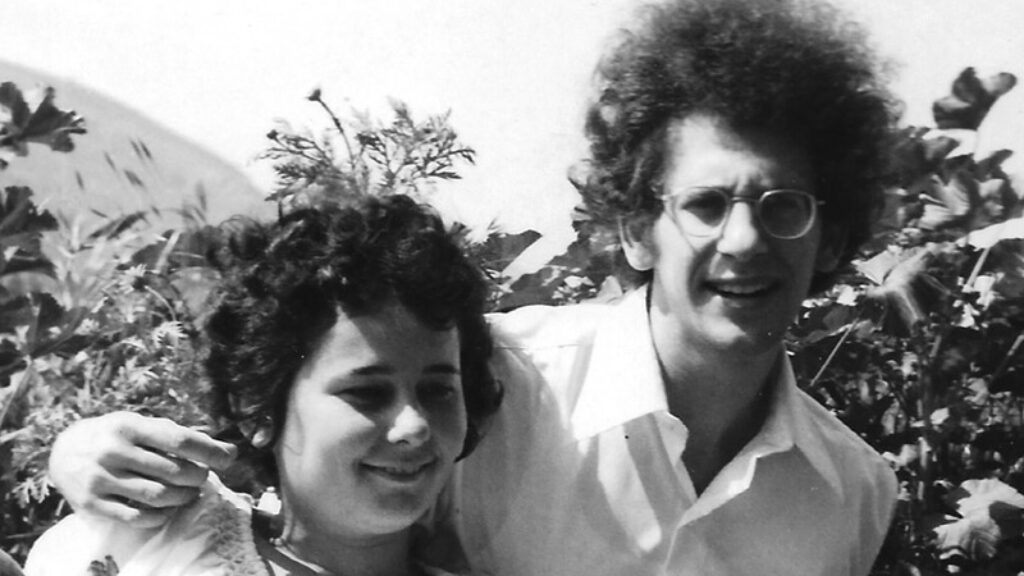

Love, Counter-Historical Style

Love letters to Israel, Judaism, and each other from Rachel and David Biale.

Sometimes a Bag Is Just a Bag

Daphne Merkin's new collection is signature Merkin: funny, smartly written, and utterly self-indulgent.

In and Out of Time

A new collection of Heschel's writings plucked from obscurity and presented with clarity to English readers adds to our understanding of the centrality of time in Heschel’s worldview.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In