Wisdom and Wars

My first copy of Seven Pillars of Wisdom, T.E. Lawrence’s epic account of leading a Bedouin guerrilla force against the Turks in the First World War, was a stolen one. It was I who stole it. At the time—it was in 1973—my wife and I were living in a rented apartment in Haifa whose owner had left us a few furnishings that included a small bookcase. One book caught my eye immediately. A large, deluxe volume, it had a brown cloth binding with a stamped leather spine and heavy, brown-tinted pages whose signatures or “gatherings,” as they are called by printers, were uncut. Using a razor blade, I sliced my way carefully past the title page, a dedicatory poem, a lengthy table of contents, and a brief introduction, and came to Chapter I. Its first sentences were:

Some of the evil in my tale may have been inherent in the circumstances. For years we lived anyhow with one another in the naked desert, under the indifferent heaven. By day the hot sun fermented us; and we were dizzied by the beating wind. At night we were stained by dew, and shamed into pettiness by the innumerable silences of stars.

I thought, “Wow!” And when I had read to the end, I thought, “No one who hasn’t cut its pages deserves to own a book like this.” And so when we moved out, I took with me the handsomely printed and illustrated 1935 American edition of Lawrence’s book, which—published the year of his death—was a facsimile of the 1926 subscribers-only British edition, which was a revision of the first, eight-copy 1922 Oxford edition, which was partially rewritten from scratch after much of the original manuscript was lost by its author in a London train station in 1919.

There’s more to the story. A few years later, I went on a long camel trip in Sinai, then still under Israeli control. A Bedouin handled the camels; our small group’s guide was a young man who knew every twist and turn of the desert, each wadi and gulley, as an experienced cab driver knows the streets of his town. The wadis were the desert’s streets, some the breadth of many boulevards, others as narrow as an alley in a casbah. One night before dawn I was wakened in my sleeping bag by the vast, deep silence all around me. I opened my eyes. Our cameleer was on his knees at prayer; our guide was staring thoughtfully at a sky wild with stars while waiting for coffee to boil over a twig fire. Without being asked, he rose and brought me some. “Thank you,” I said, by which I meant “for all this.” Back in Israel, I gave him my copy of Lawrence’s book in appreciation.

That expiated my sin, or so I thought. Yet I missed my Lawrence. God sent me an old college friend who was touring Israel. He stayed the night and left by his bed a tattered paperback of Seven Pillars of Wisdom (we hadn’t mentioned the book between us) that he had forgotten to pack. On my next round of army reserve duty, I took it along to read. It wasn’t my deluxe facsimile volume, but I was wowed again.

What happened to that tattered paperback, I can’t say. Perhaps I forgot it in my kitbag for another soldier to find, perhaps someone stole it from me. Life has its concatenations. One way or another, I was Lawrence-less again for many years. And then, not long ago, I walked into a bookshop in London and there it was: the same leather-spined Doubleday, Doran & Company edition that I had stolen 40 years before. I bought it even though it wasn’t cheap. How could I not have? That’s the copy in which I’ve just finished reading Seven Pillars of Wisdom for the third time.

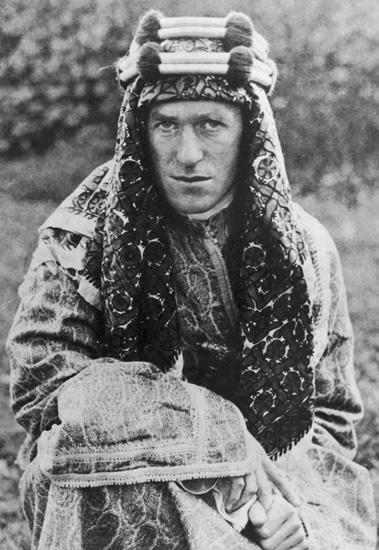

Lawrence, when the war broke out in the summer of 1914, was, outwardly, an unlikely figure to emerge as its most famed military hero. Twenty-six years old, uncommonly short and slightly if strongly built, he had no military training and was a loner by temperament. His background was déclassé Anglo-Irish aristocracy, his father having been a well-off landowner who scandalously left a fortune and a wife for their daughters’ governess. Living under an assumed name to elude disgrace, the Lawrences, as they called themselves, had five sons. The second, born in Wales, was named Thomas Edward, or Ned.

An adventurous boy with a fondness for books, pranks, ascetic tests of endurance, and romantic daydreams of heroic feats, Ned Lawrence attended high school and university in Oxford, where he read history and wrote a thesis on medieval fortifications that took him on a 2,400-mile bicycle trek through France. This led to a lengthy walking tour of crusader castles in Syria, Lebanon, and Palestine, all part of the Ottoman Empire; to a position as a technical assistant, and eventually a crew foreman, for several seasons of digging at a British archeological excavation at the northern Syrian site of Carchemish; to a job mapping southern Palestine and Turkish-controlled Sinai for the Palestine Exploration Fund, which was partly a front for British intelligence; to an appointment, when the war started, as a civilian cartographer with the British general staff in London; and to a second lieutenant’s commission and transfer to British military intelligence in Cairo after Turkey joined the fighting several months later.

Here Seven Pillars of Wisdom begins. (The book’s puzzling title, taken from the verse in Proverbs, “Wisdom has built her house, she has hewn out her seven pillars,” was a hand-me-down from a planned earlier book, never written, about seven of the Levant’s great cities.) After a lengthy survey of the pre-war Middle East and Arab world, the narrative tells of Lawrence’s accompanying a British military mission to the Red Sea port of Jeddah in order to explore the possibility of an Arab revolt against the Turks under the sponsorship of Hussein, sharif of Mecca; of his successful wooing of Hussein’s son Feisal to head the uprising with promises of post-war Arab independence; of his becoming Feisal’s confidant and the coordinator of ties between the rebels and the British command in Cairo that funded and supplied them; of developing into a field commander himself, leading Bedouin raids on Turkish positions and on the crucial railroad line running through Syria to the Turkish garrison in Medina; of advancing with his men up the Red Sea coast, capturing its northernmost point of Aqaba, and moving on to what is now Jordan while a British army pushed from Sinai into western Palestine; of linking up with the latter in its final, autumn 1918 offensive that brought about a Turkish collapse; and of triumphantly entering Damascus shortly before the Turks surrendered, followed by their German allies.

This is, of course, a mere synopsis. What make Lawrence’s book so wonderful are its extraordinary powers of observation, the magnificence of its prose, and its dark, brooding vision, already articulated in its opening pages, of the perversity of high ambition, whether this be the pursuit of glory on the battlefield or of distinction among men—a vision that carries the reader, like a riptide, counter to the military victory with which the story concludes. If one were to read it as fiction (and some biographers of Lawrence have argued for doing so, less in literary appreciation than in their eagerness to expose its alleged deceits), Seven Pillars of Wisdom would be the greatest war novel in English literature.

Its descriptions are stunning. Lawrence was a great admirer of Charles Doughty’s Travels in Arabia Deserta, for whose third edition he wrote an introduction, and it is hard to outdo Doughty in writing about the desert, but Lawrence did. Here is a sample, a scene that finds him ill with dysentery on a rest stop during a forced camel march:

The bed of the valley was of fine quartz gravel and white sand. Its glitter thrust itself between our eyelids; and the level of the ground seemed to dance as the wind moved the white tips of stubble grass to and fro. The camels loved this grass, which grew in tufts, about sixteen inches high, on slate-green stalks . . . At the moment I hated the beasts, for too much food made their breath stink; and they rumblingly belched up a new mouthful from their stomachs each time they had chewed and swallowed the last, till a green slaver flooded out between their loose lips over the side teeth, and dripped down their sagging chins . . . [O]n another day this halt would have been pleasant to me; for the hills were very strange and their colours vivid. The base had the warm grey of old stored sunlight; while about their crests ran narrow veins of granite-coloured stone, generally in pairs, following the contour of the skyline like the rusted metals of an abandoned scenic railway.

This scene takes place the morning after Lawrence has shot one of his Bedouin for killing a man from another tribe. Fearing a tribal blood feud, he is faced with:

[a] horror which would make civilized man shun justice like a plague if he had not the needy to serve him as hangmen for wages . . . It must be a formal execution, and at last, desperately, I told Hamed [the murderer] that he must die for punishment, and laid the burden of his killing on myself. Perhaps they would count me not qualified for feud. At least no revenge could lie against my followers; for I was a stranger and kinless.

I made him enter a narrow gully of the spur, a dank twilight place overgrown with weeds . . .

I stood in the entrance and gave him a few moments’ delay which he spent crying on the ground. Then I made him rise and shot him through the chest. He fell down on the weeds shrieking, with the blood coming out in spurts over his clothes, and jerked about till he rolled nearly to where I was. I fired again, but was shaking so that I only broke his wrist. He went on calling out, less loudly, now lying on his back with his feet towards me, and I leant forward and shot him for the last time in the thick of his neck under the jaw.

This is the first time Lawrence has killed anyone at close range, and mixed with the horror of it is an unmistakable physical excitement. He does not comment on the incident again, but to his readers it is one of a series of revelations of his growing engulfment in the close, all-male, homoerotic world of the Bedouin raiding parties he rides with in Arab dress, now tender in their friendships, now pitiless in their bloodlusts and cruelty, especially to the defenseless and weak. Weakness—in character, in courage, in the capacity for prolonged hardship and privation demanded by desert life—is the Bedouin’s idea of ultimate vice. Never arousing his pity, it always incites his contempt.

But the contempt that Lawrence comes to feel for himself in the desert is not because he is weak. On the contrary, he proves to be astonishingly strong, able to withstand hunger, thirst, fatigue, illness, and extremes of heat and cold better than most Bedouin. Rather, he is plagued by the consciousness of how his finely bred English soul thrills to the brutally elemental life he is living while he lives it as an imposter and a traitor, since his English values and loyalties are ineradicable and the men he leads do not know that all his promises are worthless and that they are simply being used by the British to help defeat the Turks—after which, in accordance with the secret Sykes-Picot Agreement of 1916, England will carve up the Middle East together with France and rule it in Turkey’s place.

Scott Anderson’s newly published Lawrence in Arabia: War, Deceit, Imperial Folly and the Making of the Modern Middle East deals at length with the imperialist intrigues that Lawrence was a guilt-ridden party to, a willing agent of British policies he opposed. Anderson, who views the Sykes-Picot Agreement as the root of all the Middle East’s subsequent troubles, has sought to tell the story of the behind-the-scenes diplomatic maneuvering that went on during and after World War I by focusing on four young men who were involved in it and whose paths sometimes crossed. Lawrence, the only one of the four to have fought in the war, is the lead character. Cast in supporting roles are Aaron Aaronsohn, a Palestinian agronomist, botanist, and geographer who co-headed the NILI spy ring, a Palestine-based Jewish espionage operation that worked for the British; William Yale, a blue-blooded descendant of the founder of the university of that name, representative of the Standard Oil company in Jerusalem, U.S. intelligent agent, and advisor on the Middle East to the U.S. delegation at the 1919 Paris Peace Conference that settled the fate of the dismembered Ottoman Empire; and Kurt Prűfer (Anderson prefers the Anglicized spelling “Curt”), a German orientalist and wartime chief of Germany’s intelligence bureau in Constantinople.

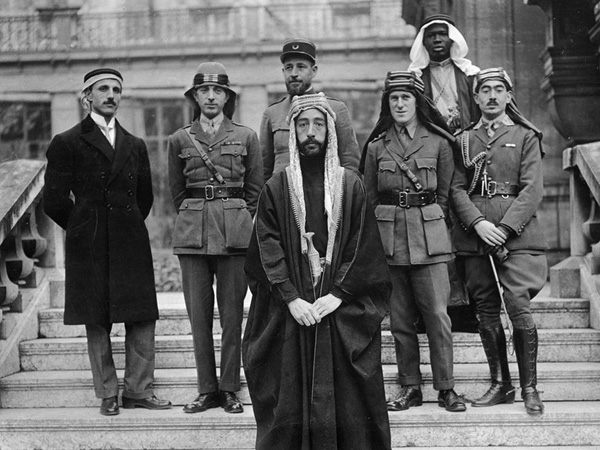

Feisal’s revolt, though not militarily indispensable to the British victory, aided it by pinning down large Turkish forces that might otherwise have been transferred to western Palestine; it also won Feisal a seat at the Middle East deliberations of the Paris conference alongside the war’s winning powers, delegations of former Ottoman minorities like the Armenians, Kurds, and Lebanese Christians, and representatives of the Zionist movement (the latter given an official status at the talks by the 1917 Balfour Declaration). As Feisal’s trusted adviser, Lawrence, who already knew many of the British diplomats in attendance from his frequent wartime visits to Cairo, helped formulate and present Arab demands while conveying back British positions and mediating between the two. Staunchly pro-Arab and anti-French, he was unsuccessful in his efforts to override Sykes-Picot, which gave France control of Syria and Lebanon. He was, however, a factor in England’s eventual if tardy decision to create a semi-independent Iraq ruled by Feisal after the latter’s expulsion by the French from Damascus; a semi-independent Transjordan with Feisal’s brother Abdullah as its king; and a fully independent Arabian peninsula under Hussein (soon to be deposed by his rival, Abdul Aziz ibn Sa’ud.) A major player in the Middle East theater during the war, Lawrence continued to be one afterwards.

This can’t be said of either Yale or Prűfer. While both were interestingly oddballish characters who serve Anderson’s narrative purposes well and enable him to expound on German and American strategy in the Middle East, neither wielded much influence at high levels or had a significant impact on the war’s course and aftermath. Prűfer lived long enough to became a Nazi diplomat; the most piquant disclosure in Anderson’s book is of a romantic affair he had in Jerusalem, in 1914–1915, with Chaim Weizmann’s sister Minna, whom he enlisted as a German intelligence agent. (Hushed up afterwards by Prűfer, Weizmann, and whoever else knew about it, the story is documented by Prűfer’s diary and other sources.) Yale ended up a professor of history at the University of New Hampshire, an anti-Zionist, and something of an anti-Semite. He served as a Middle East specialist for the State Department’s Office of Postwar Planning during World War II and as an assistant secretary to the United Nations’ Council on Trusteeship right after it.

Aaronsohn was a different story. The NILI ring’s contribution to England’s Palestine campaign was substantial, and the contacts Aaronsohn made through it, combined with his geographical knowledge of the area, assured him an important place in the Zionist delegation to the Paris conference until, while it was still underway, he died in an airplane crash.

The NILI (run from the Jewish farming village of Zikhron Yaakov south of Haifa, with a second base in nearby Atlit) was a dramatic, if not melodramatic, affair. (Not for nothing was my book A Strange Death—part of which deals with the World War I period in Zikhron, where my wife and I have lived since leaving Haifa in 1973—luridly subtitled by its publishers A Story Originating in Espionage, Betrayal, and Vengeance in a Village in Old Palestine.) Aaronsohn and his younger sister Sarah, who came from a local family, were two of the ring’s leaders; a third, Yosef Lishansky, was for a while Sarah’s lover; the fourth, Avshalom Feinberg, was in love with Sarah, too, while engaged to her sister Rivka and was killed—some suspected Lishansky of killing him—before the ring became fully operational in early 1917. It was then that it began transmitting to the British command in Cairo large amounts of information on Turkish bases, installations, armaments, logistics, military concentrations, and troop movements, in addition to detailed descriptions of the physical terrain that the British army would have to cross in a Palestine offensive.

Commanded by General Edmund Allenby, this army, having advanced across Sinai, was stalled at the gates of Gaza, where it had twice hurled itself against the Turkish trenches and twice been beaten back. In its third attack, made in November 1917, it feinted yet another frontal assault while swinging its main body eastward to Beersheva, taking the Turks by surprise, forcing them to retreat from their Gaza positions under threat of encirclement, and opening the way for a speedy British conquest of Jaffa and Jerusalem. By then the NILI was gone, nearly all its members having been rounded up by the Turks in October. (Sarah killed herself after being tortured; Lishansky was caught following a long chase and hanged in Damascus.) Yet although Anderson, oddly, does not write about this, the British flanking movement was heavily based on NILI intelligence, and Aaronsohn, who was in Cairo until September, editing and interpreting the reports the spies sent and coordinating their activities with Allenby and his staff, had been pushing for it for months.

Aaronsohn and Lawrence met several times in Cairo in the course of 1917. They appear to have taken an instant dislike to each other. Aaronsohn is not mentioned in Seven Pillars of Wisdom. Lawrence, however, appears more than once in Aaronsohn’s diaries. In the longest of these entries, partly quoted from by Anderson, Aaronsohn wrote:

This morning I had a talk with Captain Lawrence. It was an interview without the least sign of friendliness. Lawrence has had too much success at too early an age. He has a very high opinion of himself. He lectured me on our colonies, on the spirit of [our] people, on the feelings of the Arabs, on why we would do well to be absorbed by them, etc. While listening to him I could almost imagine that I was attending the lecture of a Prussian scientific anti-Semite expressing himself in English . . . He is openly against us. He must be of missionary stock.

Omitted by Anderson and indicated by the ellipsis were additional remarks concerning Aaronsohn’s request to Lawrence that his Bedouin be prevented from raiding Jewish colonies in the Galilee across the Jordan. “Lawrence,” Aaronsohn wrote, “will use the means at his disposal to conduct his own investigation of the state of mind of the Jews in the Galilee colonies. If they’re pro-Arab [Revolt], their necks can be saved. If not, their throats will be cut. He’s still at an age, the happy pup, at which one never doubts one’s powers.”

Twelve years older than Lawrence, and double his size and weight, Aaronsohn rarely doubted his own powers. Both men were headstrong, sure of their opinions, convinced (no doubt rightly) that they were better versed than any British intelligence officer, and disdainful of whoever disagreed with them. Nor, though Aaronsohn had a low estimation of the Bedouin that Lawrence led, were the two of them in disagreement about everything: Both were against a French presence in a post-war Middle East, and both wished the region to be under British hegemony. (Lawrence thought any future Arab state or states should have British dominion status.) Their visceral reaction toward each other can only be explained by fierce rivalry resulting from the similarities between them. Each was a maverick running a peripheral part of the British war machine not strictly under its control; each was jealous of his independence from Cairo while bidding for its attention and support and resenting competition; each considered his role to be of supreme value and belittled that of the other. They were more alike than they thought.

Moreover, Lawrence was by no means the anti-Zionist that Aaronsohn took him to be, although he may have given that impression in their encounters as a way of asserting his primacy. In itself, Zionism did not greatly interest him; he judged it not in its own terms but by its likely effects on British policy and Arab welfare; yet his estimate of these effects, while fluctuating over time, was not on the whole negative. His first recorded pronouncement on Zionist settlement, indeed, made in a letter written to his parents (and missing from Anderson’s book) while on his 1909 walking tour of crusader castles, was highly positive. After describing the desolate look of the Palestinian landscape, he stated, “The sooner the Jews farm it all the better: their colonies are bright spots in a desert.”

It was only after the war, however, that Lawrence, as Feisal’s diplomatic aide-de-camp, was forced to think seriously about Zionism. The position he took was moderately pro-Zionist. Feisal was under opposing pressures from Arab nationalists who wanted him to reject all Zionist claims and a British government struggling to reconcile the Balfour Declaration’s clashing commitments to both a Jewish “national home” in Palestine and the safeguarding of Arab rights there. Already toward the war’s end Feisal had met in Aqaba with Weizmann, then president of the British Zionist Organization—a meeting that, while yielding no concrete results, was by all accounts cordial. (Although Lawrence had left Aqaba the week before on a military mission, there is no reason to accept Anderson’s interpretation of this as a snubbing of Weizmann on his part.) Now, at the Paris Conference, the British worked to produce a formal accord between them.

Lawrence was very much part of these negotiations, which led to a nine-point agreement that offered Zionist support for a French-free, pan-Arab state reigned over by Feisal, still installed at the time in Damascus, in return for Arab acceptance of a British-governed Palestine in which “all necessary measures” would be taken “to encourage and stimulate immigration of Jews on a large scale, and as quickly as possible to settle Jewish immigrants upon the land.” Weizmann, who was by then president of the World Zionist Organization, couldn’t have asked for more. The Balfour Declaration hadn’t promised the Jews a sovereign state, and though this was the goal of most Zionists, it was a far-off one. Unimpeded Jewish immigration, which alone could lay the grounds for such a state, was Zionism’s immediate need. Feisal would never have endorsed it had not Lawrence counseled him to.

The Weizmann-Feisal agreement was soon consigned to the scrapheap of history by inevitable Zionist-Palestinian Arab conflicts that one would have thought Lawrence would foresee. Perhaps he did and considered it best to ignore them; perhaps he didn’t give much of a hoot what happened in Palestine as long as Feisal’s ambitions were fulfilled. It was Feisal and his Bedouin that he cared about; the urban and rural Arab of the Fertile Crescent arching from the Mediterranean to Mesopotamia had never captured his imagination. His love was for the desert with its great emptiness that human passions could never stain and for its dwellers with their proud, harsh, world-renouncing code. This was, in its British version, his code too, as would be demonstrated in the years to come, in which he was to re-enlist as a private in the Royal Air Force and remain there as a lowly technician until close to his death in a motorcycle accident.

Yet it also may be that Lawrence, though he also wrote a memorandum for Feisal objecting to the more “radical Zionists” who thought the Arabs of Palestine should simply “clear out,” had a certain sympathy for Zionism. Hardly a Christian by intellectual conviction, he had been raised by Bible-reading, Low Church parents, their piety spurred to penitent heights by their out-of-wedlock cohabitation, of the type that had produced many a Christian Zionist in England; his few known post-Paris utterances about Zionism—none cited in Anderson’s book—are intriguing. In a letter, for example, to the Anglican bishop of Jerusalem, who had asked him to repudiate his dealings with Weizmann, he wrote: “Dr. Weizmann is a great man whose boots neither you nor I, my dear bishop are fit to black.” And to William Yale he declared presciently, without condemning such an eventuality, that the Jews of Palestine would have to establish and defend a state of their own by force of arms.

Contrarily, in a collection of essays about him published two years after his death, Lawrence’s brother Arnold expressed the opinion, based on talks with him, that he “anticipated a long-protracted British administration of Palestine, ending in a comparatively amicable solution of the problem, in favor, I think, of a Jewish majority in the distant future.” Though this and the letter to Yale (whose date I have been unable to determine) don’t square with each other, both suggest that the idea of a Jewish Palestine did not distress Lawrence. And had he lived longer, he would not, I think, have agreed with Anderson about the effects of Sykes-Picot. No one despised Sykes-Picot more than he did, but he knew the Arabs of the Fertile Crescent well enough to grasp that their mutual rivalries and hatreds would sooner or later erupt chaotically in a pan-Arab state, too, if not in Feisal’s lifetime, then certainly after it.

The poem at the front of Seven Pillars of Wisdom, dedicated to “S.A.,” begins with the stanza:

I loved you, so I drew these tides of men into my hands

and wrote my will across the sky in stars

To earn you Freedom, the seven pillared worthy house,

that your eyes might still be shining for me

When we came.

It is generally agreed that S.A. was an Arab boy called Dahoum, befriended by Lawrence at Carchemish, whose real name may have been Salim Ahmed. Although the bond between the two was strong and lasted all the years of the dig (Dahoum died before Lawrence could see him again), it does not seem to have been overtly sexual. While Lawrence clearly had homosexual tendencies, his fear of sexual relations was great, and his assertion in later life that he had never freely engaged in any was probably true.

Other identities have also been suggested for S.A., including Sarah Aaronsohn—who, it is said, Lawrence might have met in Cairo in 1917. For its advocates, this improbable theory is strengthened by several testimonies, like the one given by the Australian writer Douglas Duff, of being told by Lawrence that Sarah was the poem’s addressee. But Lawrence loved to pull legs, especially when it came to his own life, and he was undoubtedly doing so in this case. The “Lawrence of Arabia” legend that formed around him both repelled and delighted him (repelled because it delighted); one way of coping with it was by means of tall tales that heightened it further while mocking the credulity of those who believed in them. It was in large measure Lawrence’s penchant for spinning often contradictory and obviously false yarns about himself that first led some historians to doubt the factuality of Seven Pillars of Wisdom.

Nevertheless, subsequent research has shown that most of what is checkable in the book is reasonably accurate—and the most controversial of its episodes still under challenge hardly qualifies as a tall tale. The most painful thing that Lawrence ever wrote about himself, it was not, whether fully, partially, or not at all true, calculated to enhance his reputation or amuse.

This episode is related in a passage telling how, in late 1917, Lawrence was raped by Turkish soldiers after being arrested while reconnoitering in the town of Deraa, a strategic railroad junction near the present Syrian-Jordanian frontier. First, he writes, he was brought to the local governor, who tried to have sex with him; rebuffed, he turned Lawrence over to his men for a whipping. Following a description of the agony of this, the narrative continues:

At last when I was completely broken they seemed satisfied . . . I remembered the corporal kicking with his nailed boot to get me up; and this was true, for next day my right side was dark and lacerated, and a damaged rib made each breath stab me sharply. I remembered smiling idly at him, for a delicious warmth, probably sexual, was swelling through me; and then that he flung up his arm and hacked with the full length of his whip into my groin. This doubled me half-over, screaming . . .

By the bruises they perhaps beat me further: but I next knew that I was being dragged about by two men, each disputing over a leg as though to split me apart: while a third man rode me astride.

Lawrence is then washed and bandaged by an Armenian medic and put in a room, from which he escapes by climbing through a window and hitchhiking a ride on the rump of a camel. “That night,” the chapter ends, “the citadel of my integrity had been irrevocably lost.”

Many objections have been raised to the veracity of this story. Lawrence, it is claimed, could not have been in Deraa at the time he said he was; had he been arrested there, he would have been recognized and treated differently as someone with a price on his head who was of inestimable value to Turkish intelligence; nor could he have escaped in the manner that he described with the wounds that he described; nor was there anything noticeably wrong with him when he rejoined his forces. Moreover, he afterwards wrote different versions of the story, told it differently to different people, and denied to some that it had ever happened.

The weight of the evidence, however, is that something did happen at Deraa by which Lawrence was tormented for the rest of his life, just as he was tormented by what he felt was his betrayal of the men he led—and if it was purely a figment of his imagination, this would only make Seven Pillars of Wisdom an even greater literary achievement. Indeed, if one were writing a novel about the loss of “the citadel” of a man’s integrity—the double loss, once as a leader in battle and once as a remarkably alive but sexually repressed human being in an environment daily testing one’s repressions—a culminating scene in which the hero catastrophically takes pleasure in his own violation would be a stroke of genius. And why not, when Seven Pillars of Wisdom is a work of genius?

Lawrence, who knew ancient Greek, spent part of his last years translating The Odyssey. Yet Seven Pillars of Wisdom, with its rotund catalogues of quarreling sheikhs and tribes and men gone to war for an ideal that unites them for the first time as a nation, is more like The Iliad. And the tormented Lawrence vainly seeking peace in the anonymity of the ranks makes one think of the wounded Eurypylus, who says to Patroclus:

For verily all they that aforetime were bravest lie among the ships, smitten by darts or wounded with spear-thrusts at the hands of the Trojans . . . But me do thou succor, and lead me to my black ship, and cut the arrow from my thigh, and wash the black blood from it with warm water, and sprinkle thereon kindly simples of healing power.

Unlike Eurypylus, Lawrence was never healed. Seven Pillars of Wisdom, his attempt to salve the wound, as Homer puts it, with “a bitter root that slayeth pain,” is an Iliad for our age.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

A Sharp Word

From his intensive study of Hebrew and Jewish history to a surprisingly romantic Zionist congress in Basel, and the horrors of the Kishinev Pogrom, 1903 seems to have been a turning point for the young Jabotinsky.

Strategic Imperatives

In his new book, Charles Freilich examines the question of how future governments ought to cope with Israel's fundamental defense predicaments.

Total Eclipse of the Brakha

Do we make a blessing on a solar eclipse? Well, that depends if eclipses are evil or not.

Oh, the Humanity!

Would the demise or even disappearance of human beings be, on the whole, a good thing. Yuval Noah Harari seems to think so, or is at least willing to entertain the thought.

Sergei Nirenburg

What a great historical essay. I have been reading Mr. Halkin's work for many years and each time come away enlightened and uplifted - not only by the content and the scholarship evident but also, very centrally, by the sparkles of wisdom and the uncommonly elegant literary style. This piece probably started as a book review but grew so much broader and deeper than one. Delightful. If Mr. Halkin reads this: would you be interested in having some of you work translated into Russian and published in one of the Russian-language literary journals in Israel?

gwhepner

They call him Lawrence of Arabia, yet

he told Abdullah he agreed the Jews

should be allowed their homeland tents to set

west of the Jordan, territory he’d lose.

Abdullah told him what the British lion

proposed he would accept, quite clearly willing

to give the whole West Bank to Jews of Zion,

not zealously addicted to their killing.

By Lawrence Rudyard Kipling was appalled,

describing him as being too pro-Yid,

which Lawrence hardly minded being called,

not only pro-Arabia, God forbid.

[email protected]