Adventure Story

One-volume histories of Israel aren’t what they used to be. I have been reading them since the 1960s, and I can remember well enough when they were just histories of Zionism with postscripts summarizing the state’s fledgling years tacked onto them. As time has marched on, however, too often to the beat of war drums, the proportions have been largely reversed. The typical history of Israel now devotes roughly a third of its pages to the pre-independence period. This was already the case with Howard Sachar’s revision and expansion in 1996 of a book he first published in the 1970s, A History of Israel: From the Rise of Zionism to Our Time. It is likewise true of a book that Martin Gilbert published in the very same year, Israel: A History, and also of Anita Shapira’s new book bearing precisely the same title.

It is something of a surprise to see Shapira join the ranks of these and other chroniclers. Although she has written numerous important articles and edited several valuable volumes dealing with post-1948 Israel, her own research and writing have focused mostly on developments in British Palestine in the first half of the 20th century. Her very first book, based on her doctoral dissertation, was a history of the struggle over what was called “Hebrew labor,” the employment in the Palestinian Jewish economy of an exclusively Jewish labor force, between 1929 and 1939. Shapira’s most popular book was a two-volume biography (abridged to one volume in English) of Berl Katznelson, the Zionist labor leader who died in 1944. Her Land and Power, an account of “the Zionist resort to force,” ends in 1948. And even her biography of Yigal Allon, a leading figure in the political history of Israel’s first decades, deals entirely with his earlier military career and does not go beyond an account of his role in Israel’s War of Independence.

These and Shapira’s other books about the life and culture of the Yishuv are replete with penetrating insight into the complex processes that culminated in the establishment of the Jewish state. She has succeeded in portraying many of the strong and colorful figures of Israel’s founding generations in full. In her pages, their ideological and tactical debates come alive again—and so do the poets of the day, whom she strategically cites to capture something of the spirit of the times that might otherwise elude her own more prosaic efforts.

What she has done so effectively in lengthy but closely focused tomes (the original version of the Katznelson biography is more than a thousand pages long) is not the sort of thing that can be easily replicated in a general history, at least not in one that a reader of average strength can conveniently carry. One therefore approaches the mere 152 pages in Israel: A History that deal with the years prior to 1948 with the knowledge that they cannot possibly match the virtues of Shapira’s other work on this subject. Still, they have many strengths of their own.

Shapira, for one thing, has done away with all sorts of errors that have been passed through the years from one short history of Israel to another. More times than one could easily count, authors have described the small group of idealistic young socialist immigrants who came to Palestine in the early 1880s as the standard-bearers of the First Aliya. Shapira, for her part, makes it clear that this group, the Bilu, was a small and select one, and that the overwhelming majority of the earliest settlers “were middle-aged Jews who came with their families out of a combination of personal and nationalist motives,” religiously observant people who “wanted to live a free life in Palestine ‘under their own vine and fig tree.'”

There is perhaps no more enduring myth in modern Jewish history than the notion than it was the trial of Alfred Dreyfus for treason that turned Theodor Herzl into a Zionist. While acknowledging that “Herzl observed the mass indignation that followed the Dreyfus trial,” Shapira correctly insists that it was “not this trial that aroused his sensitivity to the Jewish problem (anti-Semitism), as popular belief has it,” but other experiences. Observing that the “Fifth Aliya entered Zionist consciousness”-not to mention countless history books-“as the German aliya,” she sees fit to emphasize that “most of its immigrants-as with its predecessors-came from Eastern Europe.”

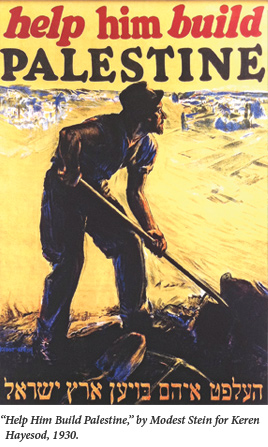

Shapira’s correction of such errors goes hand in hand with the rapid, suggestive illumination of themes that she has dealt with much more comprehensively in her other works. She eloquently elucidates literary evocations of “the new Jew” who “sought the challenge of a life in which dedication to the collective was congruent with maintaining inner truth and a life of simplicity, honesty, and self-realization.” She deftly describes how the pioneers of the 1920s remained captivated by the revolution in the Russia that many of them had left behind. They were “less influenced by communist ideology,” she explains, than they were “attracted by the fact that in that vast country a social experiment was taking place similar in character to the one occurring in Palestine.” Deeply expert in the history of the Labor Zionists, Shapira presents a concise and insightful account of the diverse aspects of their experimentation throughout the history of the Yishuv. At the same time, she clarifies its limited parameters, noting, “most of the capital invested in the country was private.” And she admits that even at its high point the socialists’ “heroic attempt to establish the alternative society and invent for it suitable cultural patterns never overcame the seductive power of bourgeois modernity.”

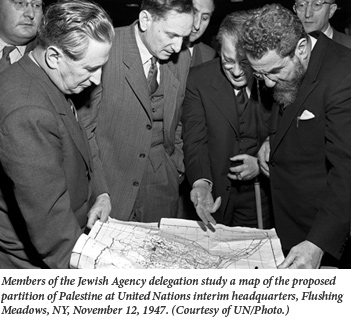

Stretching from the first articulations of Zionism in late 19th-century Europe to the establishment of the State of Israel, the first chapters of Shapira’s Israel constitute the best brief account of these matters that has yet been written. Inevitably, however, the restrictions of space have led to certain omissions, especially in the realm of politics. While Shapira touches on the subject of American Jews’ support for the Central Powers during the first years of World War I, she does not really explain how this attitude contributed to the momentum toward the adoption of the Balfour Declaration. Her outline of Vladimir Jabotinsky’s independent Zionist course concentrates on his demand for British support for a “colonization regime,” one “that would actively help build the national home by creating appropriate economic and political conditions.” She fails to explain, however, that Jabotinsky took this position because he was frustrated by the slow pace of the Yishuv’s growth during the 1920s and felt that only the British government could pay for the “big Zionism” that could solve the steadily worsening Jewish problem. And her account of the emergence of a two-thirds majority vote in the UN General Assembly in 1947 in favor of partition is regrettably terse, except with regard to the amazing turnabout on the part of the Soviet Union.

The chapters dealing with the era of statehood derive far less from Shapira’s own original scholarship, but they are not for that reason discernibly less thorough or competent. Inevitably, they focus heavily on Israel’s wars. With the exception of the War of Independence, Shapira devotes more attention to their causes and their results than to the fighting itself. She isn’t always certain that Israel’s actions can be fully vindicated, but she is very reluctant to come down on the side of those who find them blameworthy.

Shapira is, of course, familiar with all of the recent literature tracing hostile Arab actions to Israeli provocations or recalcitrance. She contrasts these claims even-handedly with opposing views and abstains from deciding between them. Did Israel’s reprisal against the Egyptian Army in Gaza in 1955 bring about “a critical change in the attitude of Egyptian president Gamal Abdel Nasser toward the conflict,” inducing him to escalate it and turn to the Soviet bloc for arms? Some say that it did, Shapiro observes, while other scholars contend that Nasser’s intensification of Egypt’s engagement on the Israeli front stemmed mostly from his pan-Arab aspirations. “Either way,” she concludes, “1955 was a year in which the status quo created by the armistice agreements became shaky.” Should Israel have agreed, sixteen years later, to Anwar Sadat’s proposals for “an interim arrangement” in Sinai that would have amounted to less than a final settlement? “Would the Israeli government have been justified in relinquishing territory in exchange for an ambiguous nonbelligerency agreement without a peace treaty?” Shapira is willing to say only that “these questions will remain open for historians to consider.”

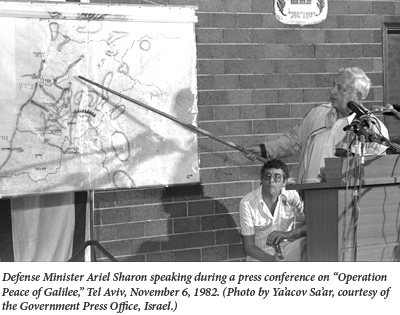

Only with respect to the First Lebanon War (her book ends before the eruption of the second one) does Shapira voice any criticism of Israel’s basic policy. In her opinion, the expanded definition of the term “war of choice” that Begin employed when he took massive action against the PLO in Lebanon “contradicted a very basic ethos in Israeli society: the defensive ethos, which shaped the worldview of generations of fighters in the Yishuv and the state. For that ethos war must always be a war of necessity, in which the nation stands on the brink.” The strategic concept that motivated this departure from past practice, Shapira contends, after a review of the overall Lebanese situation, “never had a leg to stand on.”

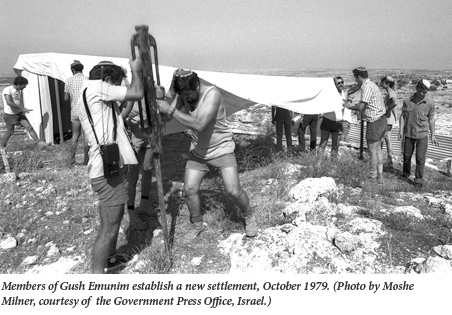

She is equally outspoken in her criticism of the people who spearheaded Israel’s post-1967 settlement enterprise. In her account of how “rule over the new territories became a leading topic in Israeli political discourse” over many decades, she often seems to stand above the fray. But her descriptions of the leaders of Gush Emunim reflect clearly enough her distaste for them. She notes that already in 1967 members of the core group that founded the organization “displayed hatred of the Arabs and total indifference to their plight, and they rejected the humanist faith in the existence of common ground between Jews and non-Jews.” They eventually formulated an ideology that did “not involve rational consideration of what is possible and desirable,” and sought to

impose a concept of faith on reality and act in accordance with it. This frame of mind ran counter to the fundamental Zionist concept that viewed the return to Zion as a project coming to fruition in the real world, while abiding by the real world’s constraints.

It also ran counter to democracy, affirming “a national-religious mission” that overrode any requirement to accept majority rule.

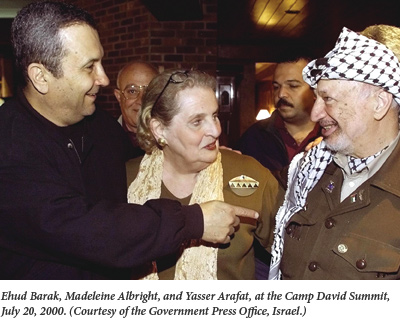

For all of that, however, Shapira doesn’t blame Gush Emunim’s legal and illegal settlement activities or Israel in general for the continuation of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. It could have been resolved, she believes, at Camp David, in 2000, if Yasser Arafat had been prepared to accept Ehud Barak’s generous offers. In the end, the summit

failed because only one of the leaders intended to reach an agreement. Arafat did not see himself as being free to make a difficult decision, either because he did not think his supporters at home were ready for it, because he feared the reaction of the Arab states, or because he thought he would be killed the day after the signing.

Throughout her text, Shapira dexterously combines a history of the Israeli-Arab conflict with an account of the political, economic, social, and cultural evolution of the Jewish state. While her far-reaching survey is always marked by an effort to achieve objectivity, she nevertheless appears on many occasions to be responding defensively, or one might say patriotically, to the kinds of criticisms that have been voiced in recent decades by the representatives of two important trends that she discusses in some detail, “the new historians” and the “post-Zionists.” The former, says Shapira, “challenged the Zionist narrative of the War of Independence and the establishment of the state, emphasizing the catastrophe that had befallen the Arabs of Israel—the Nakba.” The post-Zionists, for their part, denounce “a Zionist ‘narrative’ that bases the righteousness of Zionism on the spirit of the old labor movement ethos, while ignoring the injustice that the fulfillment of Zionism imposed on the Arabs, the Mizrachim, Holocaust survivors, women, and so on and so forth.”

Shapira is prepared to grant that the new historians have made some significant discoveries worthy of being integrated into the Zionist story, even if they have tended to stress “one segment of the reality and ignored others.” With regard to the impact of the War of Independence on the Palestinians, Shapira accepts the main contours of the case made by the leading “new historian” Benny Morris, who has exonerated Israel of the charge of seeking all along to foment a mass exodus, but also insisted that it did play a part in forcibly expelling some Arabs. While acknowledging that the Israeli Army chased the Arabs out of Lydda and Ramle, she emphasizes that this was “the only case of organized removal of entire cities on Jewish initiative.” But she also notes that from the summer of 1948 onward, “the army’s orders were to prevent Arabs from returning to their villages.” Far from regarding this policy on the refugee issue as a sign that Israel was born in sin, however, she presents justifications for it. She notes without objection the Israeli leadership’s belief that the “Palestinians had caused the war and they now bore its consequences.” She also observes, rather pointedly, that “of all the refugees created in the second half of the 1940s, the Palestinians were the only ones not absorbed by the countries where they lived.”

If she is unwilling to express any misgivings about Israel’s role in the creation of the Palestinian refugee problem, Shapira is nevertheless prepared to admit that the implementation of Zionism has in fact resulted in injustice to the Arabs who ultimately became Israelis. Already in the 1970s, their “leaders claimed that discrimination was practiced against Arabs in the education system and in allocations for building classrooms, libraries, laboratories, and sports facilities.” They also claimed that there was a plan “to keep the Arabs ignorant so as to provide manual laborers with low status and low wages,” and accused the Ministry of Education “of discrimination against the Arab heritage in its curricula in order to obscure Arab national identity.” Shapira is willing to go so far as to say that “these claims were not unfounded.” Nor are they ancient history. Even today “government allocations to the Arab sector for education, development, and industrial projects” remain “far lower than those for the Jewish sector.” The most she can say in Israel’s defense is that “discrimination is slowly but surely diminishing, and among Jews there is growing recognition of the need to prevent discrimination in the future.”

In relating how Israel handled the hundreds of thousands of Jews who fled to it from Muslim lands during its first decades, Shapira omits none of the damning evidence assembled by post-Zionists and others. Aryeh Gelblum’s virtually racist articles in Ha’aretz about North African immigrants, the midnight convoys that dumped people with no previous experience in farming in the remote wilderness spots that were to be their new homes, the systematic denigration of Mizrachi culture—it’s all here. What Shapira denies, however, is that any of this reflected any real bias or exploitative intentions. “The society that took in the immigrants did not intend to humiliate or harm them by using them as human putty. On the contrary, it believed that the faster it could bring these people from their premodern communities into the wonders of modernity, the better it would be both for them and for the State of Israel.” But whatever benefits they received from the state, and however well they adjusted to it, the Mizrachim passed “their sense of deprivation, discrimination, and affront” from generation to generation.

When the children of these Mizrachi immigrants reached adulthood, Shapira says, they “undermined the country’s existing order.” By this she does not mean, of course, that they toppled the regime but that they played a major part in deciding the 1977 election, the “about-turn” that ended the labor movement’s decades-long hegemony and brought Menachem Begin to power. This development “marked more than a change of government. It symbolized a move to center stage of new classes, another culture, a different historical narrative.”

The “about-turn” in 1977 may have symbolized a great shift, but it didn’t initiate it. Even in the best of times, Shapira repeatedly reminds us, the old collectivist ethos had strong competition. During the period of the Yishuv, there was plenty of “tension between individual aspirations to redemption and the demand that each person accept the collective’s directives.” Most Jewish workers in Palestine “were attracted to the bourgeois lifestyle, the temptations of the city, and its hedonism.” In the 1950s, Elvis showed up, and so did Gary Cooper.

Rhetorically the collectivist ethos reigned supreme and was fostered by the press, the radio, and even literature. [Yet] at the same time, an individualist ethos appeared. It did not contravene the patriotism or willingness to sacrifice of young people seeking a challenge, but it did conflict with the old social frameworks that emphasized the peer group and society at large, as opposed to the individual.

And this was only the beginning. By the end of the century, after years of globalization and privatization, “the demise of Zionist-socialist ideology” left many in “an ideological vacuum.” The “vulgarized and trivialized” popular culture as well as more sophisticated works of literature testified to “the appearance of a generation with no past and no future, interested solely in the present.”

On the one hand, the old ethos yielded to something more normal and ordinary (and thereby, somewhat paradoxically, demonstrated “how the Zionist revolution not only succeeded but became routine”). On the other hand, there was a resurgence of the very forces that secular Zionism had sought to overthrow. Among them is the ultra-Orthodox Mizrachi party, Shas, which Shapira depicts as representative of “the new identity politics that first appeared in Israeli society in 1977.” She is not sure how seriously to take its professed ambition “to convert Israeli society in its entirety to an ultra-Orthodox one in its own image,” but she does know that it constitutes an angry rejection of “everything connected with the old Israeliness” and a reassertion of Mizrachi culture. On top of this, the massive wave of Russian immigration in the 1990s consisted of people of a vastly more secular orientation who also “felt no affection for anyone with ties to a socialist past” and from the moment they arrived in the country “viewed the Zionist left with suspicion.”

Shapira herself is far removed from being one of those writers who, in her own words, speak of the demise of the old ethos “with something akin to Schadenfreude.” Nor does she fit—despite her obvious affection for all that has vanished—into the category of those who address its disappearance, as she puts it, “with painful resignation.” If anything, she ought to be grouped together with fiction writers like Ronit Matalon and Dorit Rabinyan who, in Shapiro’s own words, have “described the new Israeliness that does not grieve the passing of the old ethos, but anchors itself in the multiculturalism of the new Israel and gives it both expression and legitimacy.”

This does not mean that Shapira is prepared to say goodbye to idealism. “The assassination of Yitzhak Rabin, she writes, “opened a gaping hole in this bubble of MTV-style existence.” Many Israeli youngsters sought to cope with their grief by making peace their life’s mission.

Others volunteered for social activist causes. In the development towns appeared core groups of religious and non-religious people who had left the cities and kibbutzim and wanted to live in these towns and help their residents move ahead. This was the new volunteerism in turn-of-the-century Israel. The future will show whether it heralded a new wave of idealism, or whether it will remain a marginal event in Israeli life.

Shapira sees other signs of health in the culture. Toward the very end of her book, she contrasts the literary works of the 1980s, which expressed “the depression and confusion resulting from the loss of values and consensus in Israeli society,” and the literature of the 1990s “that engaged with nothing,” with two new books, Amos Oz’s A Tale of Love and Darkness and David Grossman’s To the End of the Land. These “two great novels,” Shapira says, “reappropriated the public sphere for literature.” They signify the replacement of “literature that documents nothingness” by “literature committed to the nation, to society, to all that is human.”

This sounds to me like wishful thinking, something in which Shapira is not usually prone to engage. Neither the new volunteerism to which she points, nor the general tenor of Israeli literature seem to me to justify her enthusiasm, guarded as it is. One ought not quibble, however, with her conclusion, at the very end of the book, that Israel is in multiple respects “a success story of global proportions.” She describes it as

a vital, vibrant society with a dynamic economy and an academy that has gained international recognition for standing at the forefront of research, a critical democracy with extreme freedom of speech and insolent and invasive media that never hesitate to expose all the government’s weaknesses . . . Israeli culture is rich, multifaceted, innovative, and constantly renewing itself, with constant confrontations within it between high and popular culture, European and American culture and Mizrachi culture, secular and religious Jewish culture, and so forth—all of which reflect its mosaic of cultural life.

Sadly, however, Shapira’s unequivocal pride in her country is not matched by a comparable measure of confidence in its future. Keenly aware of the hostility and dangers that Israel faces, she darkly wonders whether Theodor Herzl was not “mistaken in his belief that turning the Jewish people into a people like any other, with its own state recognized by the family of nations, would end anti-Semitism.” But even if he was wrong,

and in the end Israel’s existence as an independent Jewish state with military might is fraught with risks and does not ensure the existence of the Jewish people, the great Zionist adventure was and is one of the most astonishing attempts ever made at building a nation: taking place democratically, without coercion of its citizens, during an incessant existential war, and with no loss of the moral principles that guided it.

These are unsettling words—coming, as they do, from someone who is far from being an inveterate pessimist. After reading them, all I can say is that I hope to live long enough to read a good one-volume history of Israel that will adduce them as evidence of worries and concerns that the 21st century finally put to rest.

Suggested Reading

From the Middle to the End

A deceptively simple novel about a suburban, Midwestern Jewish family catapults into something annoyingly profound.

Desert Wild

Zornberg’s sessions are deeply informed by traditional Jewish sources, especially the interpretations of classic rabbinic midrash and the homilies of Hasidic masters.

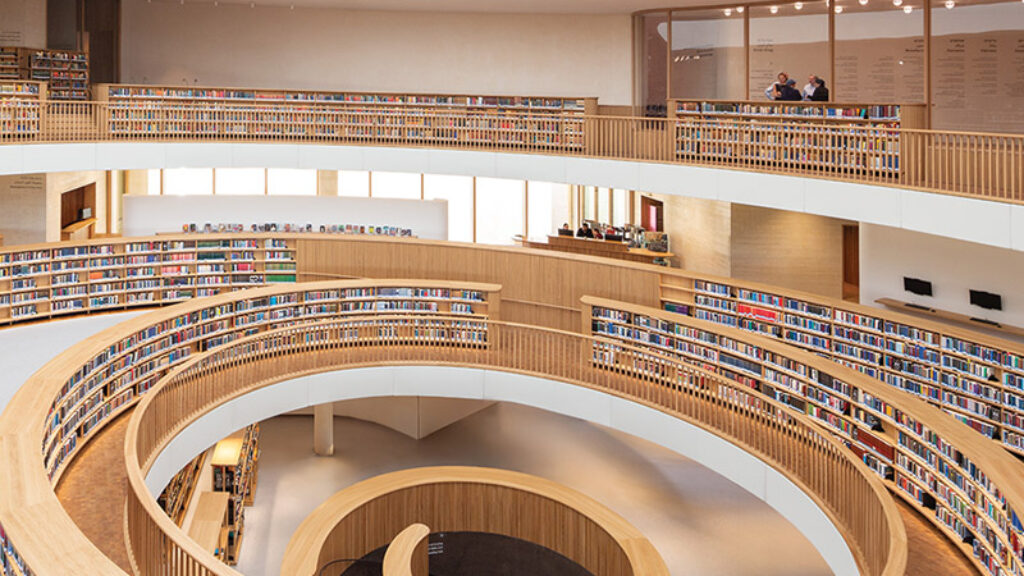

This Great House

Israel's new National Library is the most architecturally exquisite building erected in the history of the Jewish State. Like its predecessor, it’s also an excellent place to “hock” about books and ideas.

Words, Words, Words

The super sad truth about Gary Shteyngart's new novel.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In