Empty Torah Cases and “Little Purims”

The Talmud tells Jews to recite a blessing for “a miracle performed on behalf of the multitude” (Berakhot, 54a). But Jews have often gone beyond simple blessings, establishing annual festivals, some commemorating miraculous triumphs over antisemitic enemies and others marking salvation from natural disasters, wars, or disease. Whatever the occasion, such festivals were modeled on Purim, the archetype for a celebration marking escape from danger. As such, these local celebrations were often referred to as “Little Purims.”

There are more than a hundred known examples of Little Purims from Jewish communities in Europe, North Africa, and the Middle East. Some are documented as early as the 11th century C.E., but the bulk of them come from early modern Europe, especially between the 16th and 18th centuries. For example, the Jews of Medzhybizh (in Ukraine) historically celebrated a Little Purim on the 11th of Tevet in commemoration of their survival of the Chmielnicki pogroms in 1648–1649. On the 11th of Sivan, the Jews of Padua used to celebrate the so-called Purim di Fuoco (“Purim of Fire”), marking an escape from a deadly conflagration in 1795. In 1943, a Little Purim called Purim Hitler was established in Casablanca after the Allied invasion of North Africa in November 1942 prevented the deportation of the city’s Jews by the Nazis.

One of the most famous Little Purims came out of the Jewish community of Syracuse, on the island of Sicily, where a Jewish presence dates back to the times of Ancient Rome. According to local legend, in the late 1300s, a Jewish convert to Christianity named Marcus rose to prominence in the court of the Sicilian king. When the king walked through the Jewish marketplace, the Jews would parade with their most resplendent Torah cases while offering blessings in his honor. Some Jews thought it inappropriate to, as it were, place the king’s authority before God’s, and it was decided that the Torah cases should remain empty.

Marcus informed the king that the Jews’ show of respect was literally hollow. The king, outraged that his Jewish subjects appeared to be mocking him, planned to visit the Jewish market the very next morning to catch the Jews carrying empty Torah cases. When he did, their punishment would be severe: The men would be executed, women and children would be taken as slaves, and the synagogues would be burned.

That night, the prophet Elijah visited the heads of each of the 12 local synagogues in their dreams and instructed them to fill the empty Torah cases with Torah scrolls. When the king arrived the next day and ordered his men to open up the beautiful cases, he found Torahs inside.

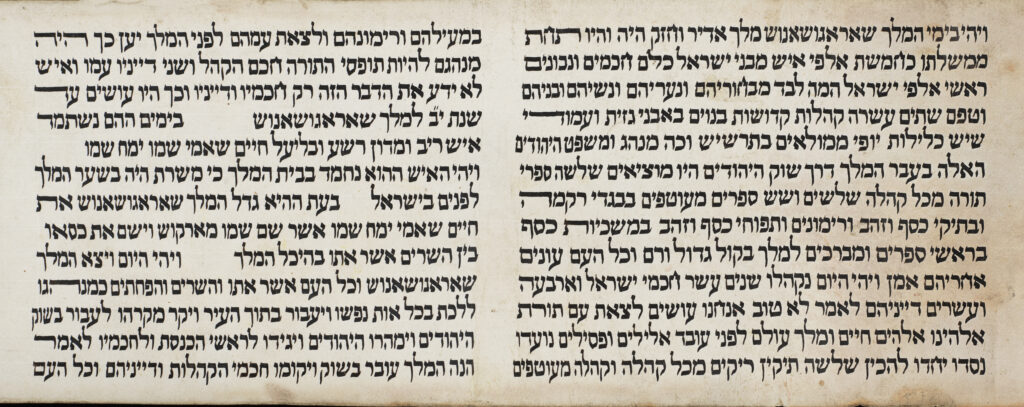

Like Haman in the story of Esther, Marcus was hung on a tree for having lied to the king, and the Jews were saved. The king even granted them special tax breaks for three years. The day of the king’s visit, the 17th of Shevat, was established as a Sicilian Purim. The story of the Sicilian Purim is preserved, in Hebrew, on a number of scrolls, modeled in both language and form on the Megillat Esther. The scroll is most often referred to as the Megillat Saragosa, because, in the scroll, the town of Syracuse is called Saragosa (not to be confused with the Spanish city).

Because Sicily was under the control of Spain in 1492, Sicilian Jews were subject to the edict of expulsion like the rest of Spanish Jewry. Some five thousand Jews were forced to flee Syracuse, after which they settled mainly in Ottoman territories to the east. The Sicilian Purim was celebrated into the 20th century by several Jewish communities in Greece and Turkey, including Ioannina, Istanbul, Thessaloniki, and Smyrna.

The Jewish community of Syracuse had been primarily Greek-speaking, and, since most of the towns in which they ended up were also Greek-speaking, they were able to maintain their language, a distinctly Jewish variety of Greek called Judeo-Greek, written (like Ladino and Yiddish) in Hebrew characters. In addition, Jews made use of unique vocabulary items, mainly words borrowed from Hebrew. For example, Judeo-Greek speakers used the word “hashekha” (darkness) to mean a church and “rimonim”(pomegranates) as a euphemism for breasts.

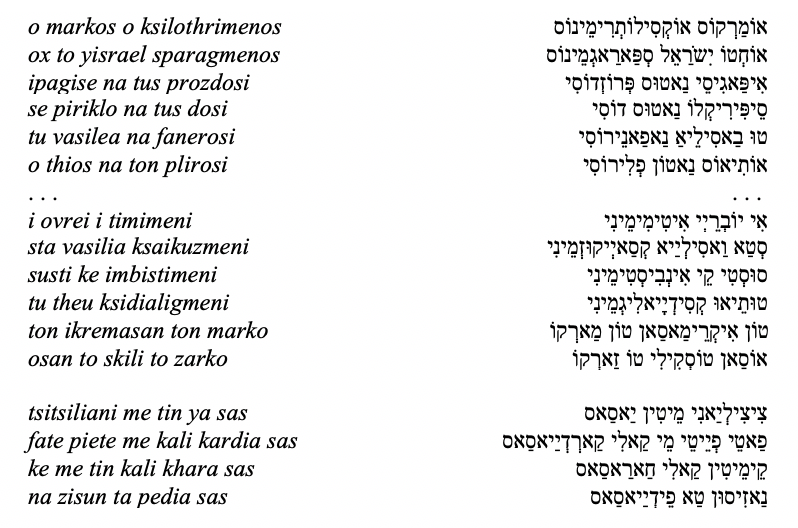

In addition to the Megillat Saragosa, which is preserved in several copies, the Sicilian Purim is also commemorated in a Judeo-Greek poem first published in Thessaloniki in 1875. The poem, which was recited (or sung), is one of only a small number of surviving original compositions in the language. Though the poem does not retell the entire story, it does make reference to all the major characters. Here are three of the poem’s 17 stanzas:

Marcus, the wicked one,

Alas, who had broken away from Israel,

He went to betray them,

To put them in danger,

To expose [them] to the king.

May God pay him back!

. . .

The Jews are honored,

Renowned to the king,

Just and righteous,

Chosen by God.

Then Marcus was hung,

Like a wretched dog.

O Sicilians, cheers!

Eat and drink merrily,

In your gladness and joy,

May your children have a long life!

The poem also includes some words that seem to be unique to Judeo-Greek. For example, in the passage above, Marcus is called ksilothrimenos, a wonderfully descriptive word that means something like “grown up with spankings” (i.e., a naughty boy!). The word “piriklo”(danger), which is derived from the Italian word “pericolo”(danger), betrays the Sicilian origins of the community.

In the aftermath of the Holocaust and the mass migrations of North African and Middle Eastern Jewish communities following the establishment of the State of Israel, most Little Purims, including Sicilian Purim, ceased to be practiced. Judeo-Greek itself was a victim of the Holocaust since the majority of its speakers did not survive the war.

There has, however, been a recent attempt to reestablish the celebration of Sicilian Purim in Syracuse itself. In 2012, more than 500 years after the Jews had been expelled from the island, a Sicilian American rabbi named Stefano di Mauro who had moved to Syracuse read the Megillat Saragosa to his newly established synagogue, thus bringing Sicilian Purim back home.

Suggested Reading

18 Questions with Jeremy Dauber: The Purim Edition

Who ruled the Borscht Belt: Allan Sherman or Lenny Bruce? Jewish comedy expert Jeremy Dauber casts his vote in a humorous interview—just in time for Purim.

Hidden Faces and Dark Corners: Megillat Esther and Measure for Measure

What happens when the hidden is revealed? Reading Megillat Esther alongside one of Shakespeare’s “problem plays” shows that question to be at the heart of Purim’s paradox.

Black Fire on White Fire

The scroll, which was originally a secular technology, became closely associated with Judaism at a time when Christians were adopting the codex for their holy books.

The Bible Scholar Who Didn’t Know Hebrew

The surprising story of Elias Bickerman and his scholarship.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In