Animal Foible

In her story “The Nurse and the Novelist,” a hilarious send-up of solipsistic Holocaust fiction, Anya Ulinich describes an imaginary bestselling novel about a young man who collects his toenail clippings in a jar without understanding why. When the man’s dying grandfather gives him an enigmatic gold charm, he travels to Belarus to find the old woman, a poetic crone, who saved his grandfather from the Nazis. Many maudlin chapters later, “it becomes clear to him why he has been collecting nail clippings in a jar, and he is able to stop.” If only.

Beatrice and Virgil, the new Holocaust-themed novel by Yann Martel—author of the mega-bestselling, Booker Prize-winning animal-fable novel Life of Pi—takes the solipsism of so much contemporary Holocaust fiction to unprecedented depths by actually being about a mega-bestselling animal-fable novelist who writes a Holocaust-themed novel. His publisher thinks it won’t sell, but Henry, the writer-protagonist, “had noticed over years of reading books and watching movies how little actual fiction there was about the Holocaust,” which makes one wonder if Henry has ever been inside a bookstore. Henry insists that what Holocaust literature needs is a book like his animal fable: “Art as suitcase: light, portable, essential—was such a treatment not possible, indeed, was it not necessary, with the greatest tragedy of Europe’s Jews?” Lest we hope that this is some sort of joke, we quickly discover that we are holding precisely that light, portable suitcase, stuffed with the light, portable bodies of six million Jews, in our hands.

The publisher’s rejection is apparently Henry’s private equivalent of genocide: “Henry now joined the vast majority of those who had been shut up by the Holocaust.” Poor bestselling Henry, a silenced victim, now roams the earth just like a survivor, immediately moving to some chichi city where he speaks the language fluently and doesn’t need a job. When an elderly taxidermist sends him a letter asking for help with a play he is writing, our hero takes the bait and visits Mr. Cryptic’s taxidermy crypt. The play’s characters, Beatrice and Virgil, unsubtly invoking Dante’s Divine Comedy, turn out to be stuffed animals, a donkey and a monkey. The Beckett-like play consists of these animals discussing their inexplicable humiliation and torture in supposedly mysterious Holocaust-like terms. Eventually, the play’s meaning is revealed: the Holocaust is the taxidermist’s metaphor for the suffering and extermination of . . . animals.

All of this could, conceivably, be worthwhile if it were a satire about the unacceptable ease and unearned moral absolution one receives by writing about the Holocaust to serve one’s own ends. The book occasionally offers hints of this, as when Henry’s wife, who refers to the donkey-monkey play as “Winnie the Pooh meets the Holocaust,” notices that the taxidermist is a creep. When (spoiler alert) the taxidermist turns out to be a creep, and Henry finally rejects him, the reader entertains the bright hope that the whole book is an unbrilliant but nonetheless ironic joke on writers who milk the Holocaust for gravitas.

But parodies are supposed to be funny—and if this is a joke, neither Henry nor Martel is in on it. The novel ends with Henry composing, as we are told in the final triumphant line, “the first piece of fiction Henry had written in years,” which is then presented as an appendix. This “piece of fiction” is a collection of imagined pseudo-literary “games” for Holocaust victims, of which the following is typical:

The order comes at gunpoint: you and your family and all the people around you must strip naked. You are with your seventy-two-year-old father, your sixty-eight-year-old mother, your spouse, your sister, a cousin, and your three children, ages fifteen, twelve, and eight. After you have finished undressing, where do you look?

These “games” are supposedly cringe-worthy because of our empathy. But the cringe they induce actually derives from something else. In order to care about how people died without bothering to care about how they lived, the reader has to be a creep.

Criticizing a novel written as a criticism-inoculated animal fable about the redemptive simplicity of art feels a bit like clubbing a taxidermed baby seal. Henry insists that he has written something brave and bold, like Orwell’s Animal Farm. But Animal Farm was published in 1945, while Stalin was a living menace. In 2010, it doesn’t take much courage to announce that the Holocaust was bad, unless one lives in Iran. And that lack of courage is the source of the Holocaust’s prurient artistic appeal.

There are certainly many brilliant imaginative works about the Holocaust, but it can also be a gold mine for lazy writers. All the hard work of developing characters and creating a moral universe is done for you, leaving only bad guys and childlike innocents who might as well be stuffed animals. Lived history is irrelevant for authors like Henry, because his story isn’t about the Holocaust or even “representations of the Holocaust.” It’s about writer’s block.

“Afterwards, when it’s all over,” one of Henry’s fictional dilemmas reads at the book’s end, “you meet God. What do you say to God?”

The answer is clear: Why can’t I stop collecting my toenail clippings in a jar?

Suggested Reading

Objective Muddles and Persuasive Testimony

It may seem as though a religious tradition like Judaism would have no home in a philosophical ecosystem that cultivates nothing but a specific mode of intellectual engagement. But it is precisely the lack of a positive dogma that makes analytic philosophy compatible with the basic tenets of Judaism—at least that’s the premise of Jewish Philosophy in an Analytic Age.

Going Public

The Jewish Jane Austen, or better?

Rocketmen

A brilliant and moving exhibit at the Israel Museum pairs the Israeli astronaut Ilan Ramon, who died in the space shuttle Columbia explosion, with the obscure biblical gure Enoch, who was also an astronaut of sorts.

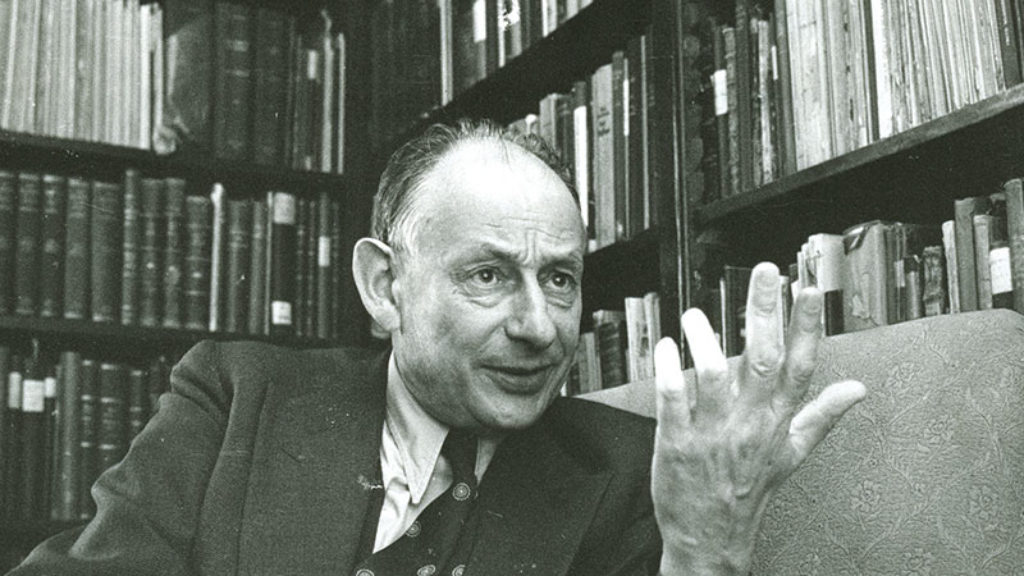

The Secret Metaphysician

While a new crop of biographies about Gershom Scholem all, in one way or another, seek to account for the great man's fascination, they are themselves evidence of Scholem’s ongoing allure.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In