Nation and Narrative

Now that the dust has settled on the enthusiastic reviews of Yossi Klein Halevi’s account of seven paratroopers who helped liberate Jerusalem in 1967, we can better understand the nature of his achievement, as well as consider some of the troubling questions his story raises. Like Dreamers is a good read in the best sense. It wears its formidable research very lightly, and it has a brisk and compelling forward momentum despite the burden of crisscrossing back and forth among seven parallel lives. Indeed, because the story seems to tell itself, we are not likely to look under the hood, as it were, to identify the critical choices Halevi has made to make this narrative engine run. Those choices tell us a lot about what it takes to write seriously about Israel.

The decision to write a longitudinal narrative of seven figures, to begin with, is not self-evident and certainly not easy. When Anita Shapira wrote her magisterial books on Berl Katznelson and Yigal Allon, she had the advantage in each case of a single stable subject with a mountain of personal and public papers. Amos Elon had another kind of advantage when he wrote his authoritative The Israelis: Founders and Sons; he could range over the whole epic story of Israel picking and choosing his examples. Although Halevi’s choice to write a limited collective portrait entails real challenges, the payoffs are substantial. He has taken on the burden of making us care enough about the lives of seven men to keep track of their exploits as he tirelessly turns from one to the other. (His compositional craft in managing hundreds of these transitions is impressive.) In doing so, he has, I think, captured something fundamental about the dynamics of Israeli society. This is a society comprising citizens with contending backgrounds and visions who, like Halevi’s paratroopers during the 1967 and 1973 wars, are capable of transcending their differences under conditions of national emergency. The book begins amidst the chaos and confusion of the battle for Jerusalem in ’67 in which these men distinguished themselves not only by their willingness for self-sacrifice but also by their capacity for improvisation. After the euphoria of the unification of the city, the narrative tracks them in their separate but parallel civilian lives—each with his set of problems—until they are drawn together again during the trauma of the Yom Kippur War, only to return afterward to their separate spheres.

It is the lives of his citizen-soldiers that Halevi keeps front and center rather than himself, and in an age of self-referential journalism this, too, is something to be grateful for as a reader. Halevi, whose first book was Memoirs of a Jewish Extremist, undoubtedly has his own continuing story to tell. Yet once he briefly identifies himself at the opening of the book as an American Jew who settled in Israel in 1982 at the age of 29, Halevi occupies himself solely with his characters, keeping himself out of the frame. It is not too much to see a parallel between his paratroopers’ readiness for sacrifice and his own renunciation of journalistic ego. Halevi has a gift for empathy that goes far beyond the requirements of professionalism, and his is a protean empathy. He is as capable of neutralizing our revulsion for Udi Adiv, the kibbutznik who traveled to Damascus in 1972 to help create an anti-Zionist terrorist underground, as he is capable of forestalling our judgment of Hanan Porat’s tacit endorsement of the crimes of the settler underground. Yet if Halevi as a figure is absent from the story, the shaping will of his moral imagination is not. The sensitive reader can tell when Halevi has to screw up his nerve to help us understand unsavory behavior and when his empathy is given unstintingly. But even when his sympathies are evident, they are never given away to one side of the Right/Left, religious/secular divide. Yoel Bin-Nun, a former Mercaz Harav student who became a founder of Gush Emunim, is invested with as much legitimate sincerity as is Arik Achmon, a kibbutznik who helped lead the crossing of the Suez Canal during the Yom Kippur War and later led the move toward privatizing the Israel economy.

Does Halevi’s capacity to understand both sides of the divide come from his position as an outsider, as an American immigrant? I think it makes a difference, as does the fact that he had an Orthodox upbringing. The greatest contribution of Halevi’s Americanness is to open up for English readers the intimate codes of behavior and communication in Israeli civil and military life. Even for Americans who know Hebrew, read the newspapers, and spend time in the country, there is a dense texture of nativeness—the nicknames, the popular songs, the IDF slang—that can rarely be penetrated. This is doubly the case when it comes to the inner worlds of such total institutions as the kibbutz, the hesder yeshiva, and the West Bank settlement. In addition to its more evident accomplishments, Like Dreamers performs this work of cultural translation unobtrusively without ever patronizing the reader. An untranslatable Hebrew term is introduced and deftly glossed, a government minister mentioned and identified, a stanza of a hit song woven in. Doors are opened, and we ourselves feel a little less like outsiders looking in.

The biggest risk Halevi has taken is to make his story read like a novel. Like Dreamers is constructed as a sequence of short scenes that, though they are narrated in the past tense, have a cinematic, you-are-there quality and rely heavily on word-for-word conversations. Halevi handles these materials very deftly; he avoids melodrama and cheap effects even as he deals with fraught events that can be easily tapped for stirring emotion. But the scenes are nevertheless conspicuously staged and constructed. One has the sense that over the course of many years Halevi spent innumerable hours interviewing each of his subjects—who knows how many false starts he made with subjects who disappointed or withdrew?—and then sat down at his desk with these voluminous notes and tape recordings. The labor of crafting lean, dramatically coherent scenes out of such material must have been prodigious, a little like making a pint of maple syrup from vats of sap.

The difference between fiction and the kind of journalism Halevi is practicing lies less in narrative technique than in our expectations as readers. When it comes to journalism, as opposed to fiction, there is an implicit compact between writer and reader that the narrative faithfully represents events as they took place. It’s fair play to use the writerly imagination to create a lively and persuasive simulacrum of reality as long as the tether to the historical truth remains intact. It all depends in the end on the trustworthiness we accord to the writer, and, in the case of Halevi, the good news is that our trust in him as an honest broker never wavers. But sometimes his commitment to truth-telling has to accommodate another bond: the personal connection with his subjects built up over years of visits and interviews. This requires Halevi to exercise exquisite tact in dealing with inevitable human failings, and it puts the burden on us to pick up on the hints when they are left.

My only criticism of Halevi’s recourse to novelistic techniques is that he does not take them far enough. I wish he had been a little more adventuresome in borrowing from the toolkit of modernist fiction so that his imaginative reconstructions would be a little edgier and more knotted and more challenging as writing. In his concern for the reader’s experience, Halevi’s wellspring of empathy is perhaps too generous, and this makes him favor a mode of storytelling, writerly though it may be, that is rather linear and conventional.

The strength of Like Dreamers lies in showing us how two antithetical elite institutions—the kibbutz and the religious-Zionist youth movement and yeshiva—produced exemplary soldiers who then went on to reshape Israeli society. With the kibbutz movement currently in disarray, it is useful to be reminded of its truly formative role in creating the leadership of the young state. Halevi is a good guide to the ideological differences that were fierce enough to make some kibbutzim break apart in the 1950s over their stand toward Stalin and the Soviet Union.

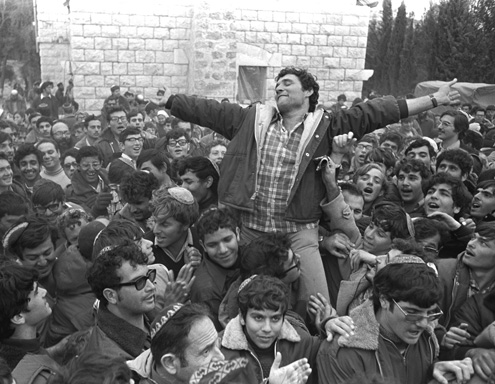

Despite the rigid adherence to principle, kibbutzim were also incubators of creativity, if we are to judge from the four kibbutzniks who are part of Halevi’s band of seven. There is Arik Achmon, the intelligence officer and entrepreneur, and Udi Adiv, the anti-Zionist activist who was eventually convicted of treason. And surprisingly, there are two artists. Avital Geva, a member of Kibbutz Ein Shemer, became a leading conceptual artist whose ecological greenhouse represented Israel in the 1993 Venice Biennale. Meir Ariel, of Kibbutz Mishmarot, wrote a counter-anthem to Naomi Shemer’s “Jerusalem of Gold” in 1967 and went on to become a Dylan-like figure and the leading poet-singer of his generation; Halevi’s affinity for Ariel and for Israeli music in general is unmistakable and infectious.

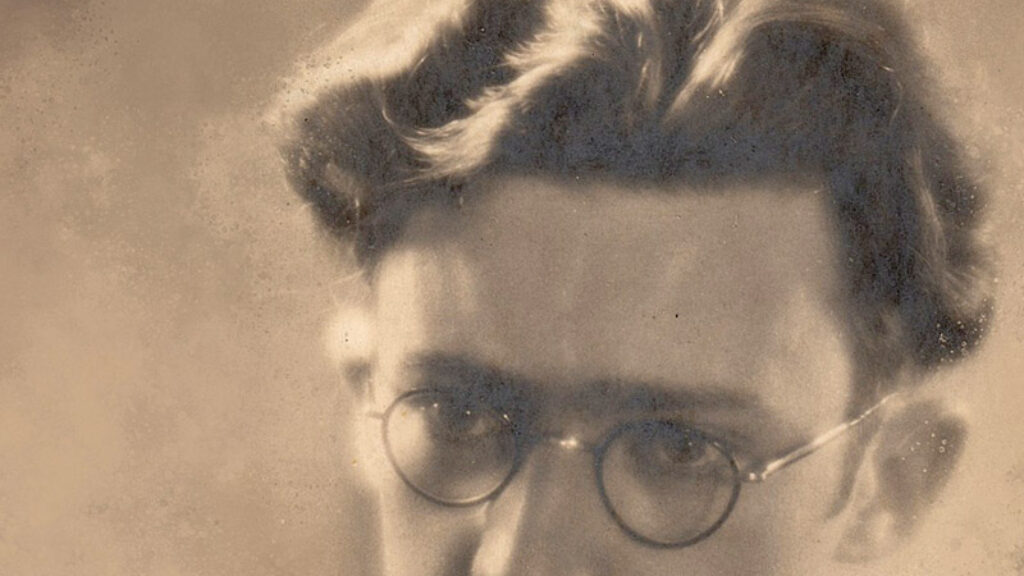

The kibbutzniks and yeshiva students fought side by side in the battle for Jerusalem in 1967, yet the meaning of their experience was refracted very differently by each group after the war. The kibbutzniks fought to counter a threat to the existence of the state against the background of the Holocaust. But when the smoke had cleared, they became increasingly uneasy about the moral price to be paid for ruling over Arabs of the West Bank. The yeshiva students, leaders in the Bnei Akiva youth movement, were aroused by a similar conviction of national peril; yet for them the war yielded a miraculous restitution. With the return of Judaea and Samaria and the uniting of Jerusalem, the severed limbs of the body of Israel had been reattached and a spark of messianic expectation ignited. Here too Halevi is a reliable guide to the authentic and fervent idealism that was rooted in the teachings of Abraham Isaac Kook, Israel’s first chief rabbi, and his son Zvi Yehudah, the head of the Mercaz Harav yeshiva, before the politicization of the settler movement and the seeding of the small but lethal underground. In addition to Yoel Bin-Nun, the Bible teacher who was a founder of Alon Shvut and Ofra, the central figure in this movement is Yisrael Harel, the founder of the West Bank settlements’ umbrella organization, the Yesha Council, and its magazine, Nekudah. But Bin Nun—the settler-rabbi who had the respect of Rabin and eventually developed not-unreasonable plans for a West Bank with Jewish and Arab cantons—may be Halevi’s most compelling subject.

The choice to follow the diverse lives of seven soldiers from an elite army unit enables Halevi to trace the origins of one of the great divides in Israeli society. Yet despite the richness of its yield, this focus inevitably means that other important stories can’t be told. Israeli Arabs, Jews from Middle Eastern lands, women, Russian immigrants, Jews from Ethiopia, the ultra-Orthodox, high-tech innovators, shopkeepers, city dwellers, foreign workers—all these groups were significant factors in the make-up of Israel during the period covered in Like Dreamers and became even more influential in the years since. Halevi is of course aware of them all, and the backdrop of his figure studies are flecked with references to new forces gathering strength in the wings.

Amidst all these changes, Halevi’s book remains fixed on the fate of Zionist idealism. Devotion to realizing a vision of a Jewish nation on its ancestral soil is the moral engine that fascinates Halevi and that he identifies as the force driving both the kibbutzniks and the settlers in the immediate aftermath of the Six-Day War. What Like Dreamers does so well is to document how this equivalence of principle shifts in the following decades. It is the young families of Gush Emunim that succeed in appropriating the charisma of the Zionist ethos; and even though their religious spirit was inimical to the Labor governments of the time, the fact that they were actualizing the old pioneering ideal won them covert sponsorship, and in the process enabled Israel to drift into becoming what Gershom Gorenberg has called an accidental empire. The call for secular youth to settle the Galilee and other places within the Green Line produced no similar results. Halevi’s kibbutznik paratroopers became entrepreneurs and artists while their religious counterparts founded new settlements that grew into towns and cities. In the meantime, the officer corps of the IDF has become increasingly populated by Zionist-religious youth, for whom the defense of the Jewish state and the willingness for sacrifice are fueled by motives beyond patriotism alone.

Israel of the 21st century is, to say the least, a complex and shifting environment. One hopes that Yossi Klein Halevi, with his unique mix of acute observation and moral empathy, will stay on the job.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

Warped Fantasies

Jews observing the resurgence of anti-Semitism in the 21st century may be forgiven for thinking that they inhabit “a warped fantasy.”

Religion and Power

Rabbi Sacks, who is in the end an optimistic thinker, sees a process of internecine violence leading to religious moderation happening within Islam now.

The Tikkun in Sutzkever’s Work

Elie Wiesel explores the soul and purpose of Holocaust poetry.

The Audacity of Faith

The career and life of Yehuda Amital—unconventional, unpredictable, and free of clichés.

gwhepner

LIKE DREAMERS

Regarding the return from Zion,

only members of the family

understand why Jews rely on

the Psalmist sympathetic simile,

comparing to great dreamers Jews,

who were before returning k’holmim,

and many then chose to abuse

because they never understood the dream.

Among the nations many said,

“God made great things occur with these,” but those

who stood the truth upon its head

laughed at them, anger coming from their nose.

[email protected]