Religion and Power

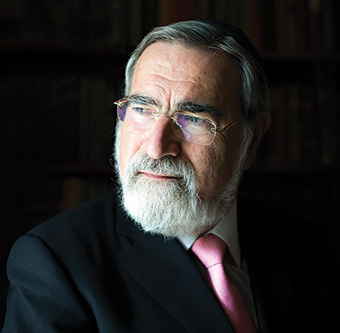

At a time of alarming nuclear tests, terrorism, and starving, half-naked refugees seeking safety, Jonathan Sacks, the distinguished theologian and former chief rabbi of Great Britain, has written an ecumenical—yet deeply Jewish—and timely tour de force about religion and violence. Not in God’s Name: Confronting Religious Violence draws upon history, theology, psychology, evolutionary theory, and, perhaps above all, close readings of biblical texts to argue that the God of Abraham—that is to say the God not only of Judaism, but of Christianity and Islam—is, properly understood, a God of life, not death; of love, not hate; of peace, not war; and of compassion, not cruelty. Which is not to say that Sacks denies that people have attempted to justify violence in God’s name.

In contrast to Hannah Arendt’s famous description of the “banality” of Nazi perpetrators of the Holocaust, Sacks calls violence in the name of a sacred cause “altruistic evil.” He elaborates:

By this I do not mean the kind of behaviour that people argue over: abortion, for instance, or assisted suicide. Nor do I mean issues like the highly complex question of civilian casualties in asymmetric warfare. I mean evil of the kind that we all recognize as such. Killing the weak, the innocent, the very young and old is evil. Indiscriminate murder by terrorist attack or suicide bombing is evil. Murdering people because of their religion or race or nationality is evil [. . .] There are acts so alien to our concept of humanity that they cannot be justified on the grounds that they were the means to a great, noble or holy end.

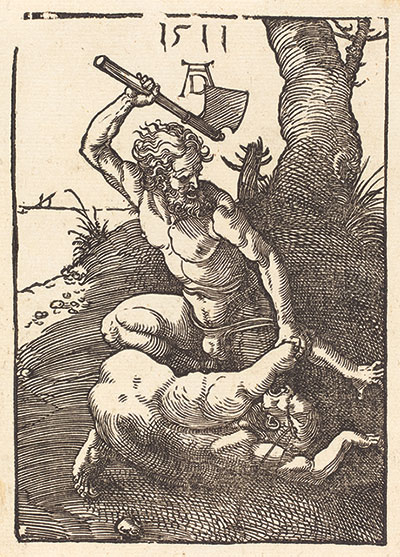

Of course, as Sacks notes, such evil has often been committed in the name of secular causes; indeed one might say that this is the story of the 20th century. But he is no simple apologist for religion either, and his argument has several steps. In the first place, he acknowledges that religions—even his own—can and have been used to dehumanize, demonize, and scapegoat others in justification of such evil. Indeed, as he writes (the italics are his), “The first religious act, Cain and Abel’s offerings to God, leads directly to the first murder.” And yet, he argues, the true intention of the biblical accounts of apparent divine favoritism and sibling rivalry, from Cain and Abel to Jacob and Esau and beyond, was not to suggest that Divine favor was a zero-sum game, but rather the opposite: a scriptural admonition not to commit violence in the name of God.

Judaism and Christianity have, according to Sacks, historically evolved away from justifying “altruistic evil,” as they learned to thrive without the power of the state. In the Jewish case, this happened with the destruction of the Second Temple and the rabbinic accommodation to powerlessness and diaspora (a point to which I shall return); with Christianity he sees this as having happened in the wake of the early modern wars of religion:

More gradually, but also more extensively, Western Christianity had to learn what Jews had been forced to discover in antiquity: how to survive without power [. . .] [This] suggests two hypotheses. First, no religion relinquishes power voluntarily. Second, it does so only when the adherents of a faith find themselves fighting, not the adherents of another religion, but their own fellow believers [. . .] You do not learn to disbelieve in power when you are fighting an enemy, even when you lose. You do when, with a shock of recognition, you find yourself using it against the members of your own people, your own broadly defined creed.

It is this process of internecine violence leading to religious moderation that Sacks, who is in the end an optimistic thinker, sees happening within Islam now. As he notes, “The primary victims of Islamist violence are Muslims themselves, across the dividing lines of Sunni and Shia, modernist and neo-traditionalist, moderate against radical,” and so on. One terrible instance Sacks cites is of a Taliban attack on a school in Peshawar, Pakistan, in which 141 people were massacred, 132 of them children.

It is clear, however, that Sacks does not think that the problem of religious violence has been solved once and for all by Islam’s older Abrahamic siblings. Sacks adduces at least three reasons that religious violence remains a problem for all of us. First, and most generally, Sacks argues (and I agree) that if the 17th century was the dawn of the age of secularization, the 21st century will be one of desecularization. As he writes, the “Abrahamic monotheisms in particular offer ordinary individuals—and we are, most of us, ordinary individuals—a sense of pride and consequence” that modern secular ideologies have failed to provide. However, while Protestants and Catholics realized in the 17th century that they had to deprive religion of power in order to stop murdering each other, this reform took place at the political level, not the deep theological level at which these issues must ultimately be addressed by each religion. Consequently, even in the Abrahamic religions which have turned away from religious violence, dangerous doctrines have lain “dormant like frozen DNA,” awaiting the return of religious power. As God warned a jealous Cain, “sin crouches at the door.”

The primal sin for Rabbi Sacks is the identification of religion with power. Polytheism, he writes on the first page of Not in God’s Name, “was the transcendental justification of the state,” in which earthly slavery, violence, and injustice were inevitable consequences of a divine hierarchy. The use of religion for such political ends is, he argues, the essence of idolatry. “Religion,” he reiterates late in the book, “seeks truth, politics deals in power.” Abrahamic monotheism should be understood, then, as a profound social and theological critique of the politicization of religion. It is useful to quote Sacks at some length on this point, both because he is perhaps the great philosophical darshan (preacher) of our time and because I think his

argument misses (or avoids) a profound point with regard to both the biblical text and the challenges we Jews face in the contemporary world.

Not all at once but ultimately it [Judaism] made extraordinary claims. It said that every human being, regardless of colour, culture, class or creed, was in the image and likeness of God. The supreme Power intervened in history to liberate the supremely powerless. A society is judged by the way it treats its weakest and most vulnerable members. Life is sacred. Murder is both a crime and a sin. Between people there should be a covenantal bond of righteousness and justice, mercy and compassion, forgiveness and love. Though in its early books the Hebrew Bible commanded war, within centuries its prophets, Isaiah and Micah, became the first voices to speak of peace as an ideal. A day would come, they said, when the peoples of the earth would turn their swords into ploughshares, their spears into pruning hooks, and wage war no more. According to the Hebrew Bible, Abrahamic monotheism entered the world as a rejection of imperialism and the use of force to make some men masters and others slaves.

Abraham himself, the man revered by 2.4 billion Christians, 1.6 billion Muslims and 13 million Jews, ruled no empire, commanded no army, conquered no territory, performed no miracles and delivered no prophecies.

It is impossible to refrain from applauding Rabbi Sacks’s eloquent summation of the deep moral truths which Abraham, our father, and the Hebrew Bible brought into the world. And yet the final quoted sentence points to a significant blind spot in this brilliant book. For, Rabbi Sacks’s eloquence notwithstanding, in biblical fact, Abraham was promised an empire, or at least “a great and mighty nation,” through whom all the nations of the earth will be blessed; he did command an army, which bested the four kings and rescued their captives; he was the recipient, if not the performer, of miracles; and he was vouchsafed the prophecy of the “Covenant between the Pieces,” which, in fact, promises specific territory and ultimate national victory. Finally, Abraham merits these promises of power precisely because he has kept the way of the Lord by doing “what is just and right,” (Gen. 18:19) that is by acting with compassionate justice and moral righteousness.

Why does Sacks feel compelled to describe such an anemic Abraham? Although Moses Maimonides once described the patriarch as a “weak” philosophical preacher, this was precisely to underline the

ultimate necessity of political action and power.

In my view, the biblical vision of the relationship between the justice required by religion and the realities of politics is more complex than a simple disjunction, in which truth and power have nothing to do with one another. I agree with Sacks that Abrahamic monotheism gave us the vision of the human being as created in the image of God. This means not only that men and women may not be violated, murdered, or enslaved, but also that they are each unique. According to a famous mishnah in Sanhedrin:

God created Adam as one individual to teach us that whoever destroys one person, it is as if he destroyed an entire world, and whoever preserves the life of one person, it is as if he preserved the entire world [. . .] A mortal being mints many coins from one prototype and all the coins are exactly alike; the King of all Kings, the Holy one Blessed be He, minted all humans from one prototype, Adam the first, and not one person is exactly like another.

Similarly, there is a talmudic teaching in Berakhot that says, “One who sees a large gathering of Israelites,

says, ‘Praised be the Wise One of secrets’, just as the minds (of human beings) are not exactly alike, so their facial features are not exactly alike.” It is precisely this uniqueness that testifies to the ultimate uniqueness of the God of Abraham; the unity that is God desires to reign over and coexist with the diversity that is humanity. But none of this requires us to assent to the depoliticized and deterritorialized Abraham described by Sacks.

As careful readers of the Hebrew Bible as different as the early modern Protestant thinkers described by Eric Nelson in The Hebrew Republic and the rosh yeshiva of Volozhin, Rabbi Naftali Zvi Yehuda Berlin (the Netziv), have argued, there is a biblical ideal of a constitutional nation-state which is integrally related to the Abrahamic vision. Indeed, only such a political enterprise can fulfill that vision of a monotheistic community devoted to compassionate righteousness and moral justice. It is the kingship of God that underwrites human freedom and justice, but these values must be enforced and defended by human beings. In short, Sacks seems uncomfortable with an Israel that actually succeeds in its Abrahamic mission of convincing the families of the earth to accept the moral and spiritual truths of monotheism.

My disagreement with Rabbi Sacks crystallizes in another eloquent passage late in the book. In interpreting Moses’ statement to the Israelites that, “It is not because of your righteousness or the uprightness of your heart that you are going to take possession of the land,” (Deut. 9:5) Sacks writes:

A chosen people is the opposite of a master race, first, because it is not a race but a covenant; second, because it exists to serve God, not to master others. A master race worships itself; a chosen people worships something beyond itself. A master race values power; a chosen people cares for the powerless. A master race believes it has rights; a chosen people knows only that it has responsibilities. The key virtues of a master race are pride, honour and fame. The key virtue of a chosen people is responsibility.

Here again, it seems to me that in his eloquence Sacks has run beyond the biblical point, and in a direction that classical Zionist thinkers, among others, saw as dangerously misguided.

It is true that the prophet Amos declared (on behalf of God) that, “You alone [Israel] have I singled out of all the families of the earth; therefore I shall hold you to account for all your iniquities.” (Amos 3:2) But a chosen people has rights as well as responsibilities—as human beings and children of God. Similarly, humility is, no doubt, a virtue, but too much of it might prevent one from insisting, as Abraham did, that everyone (even God!) must act with justice. Nor is it possible to care for the powerless while failing to value power—not as an end, but certainly as a means. Without power, how can the chosen people protect the powerless against their exploiters? And, of course, without power, how can the chosen people protect themselves?

In summing up his position, shortly after the passage just quoted, Sacks writes, “A chosen people is not a master race but its opposite: a servant community.” But that is not how the Bible describes us. Immediately before the Ten Commandments, God addresses Israel: “You shall be to Me a kingdom of priests and a holy nation.” (Ex. 19:6) The priestly mission is indeed, as the commentator Seforno explains, one of teaching the nations of the world the truths of monotheism, but this is only possible from within a kingdom, a polity. The holiness to which this enjoins us is supposed to guard against the misuse of power, but we are seen here as agents of the One Monarch, not servants but leaders working to bring about a world of compassionate righteousness and moral justice.

In this context it is worthwhile to return to Sacks’s description of the sectarian Jewish violence leading to the destruction of the Second Temple. He concludes that “Out of darkness, though, sometimes comes light. What Jews discovered when they had lost almost everything else was that religion can survive withoutpower.” This comes close to idealizing the catastrophe which led not only to almost two thousand years of galut (exile), but to the depredations of the medieval and modern periods, and, eventually, to the Shoah—all of which demonstrated the tremendous necessity of a Jewish state. Religion may be able to survive without power, but it will be unable to redeem without power. Power may corrupt, and absolute power may corrupt absolutely, but powerlessness corrupts too, for it necessitates accommodation with, and sometimes even surrender to, evil.

We will never be able to fulfill our Abrahamic mandate to redeem the world if we remain powerless. This was the original mission of Israel, and the purpose for which we returned to Zion. Sacks writes that pluralistic liberal democracy is “the best way of instantiating the values of Abrahamic monotheism,” with which I have no quarrel, but it is not clear to me that the polity he envisions is, or can be, a distinctively Jewish one. Nor is it likely to help bring a world of peace, compassionate justice, and moral righteousness.

An exchange between Rabbi Riskin and Rabbi Sacks followed.

Click here to read Rabbi Sacks’s response, “Religion and Politics.”

Click here to read Rabbi Riskin’s rejoinder, “Necessary Power.”

Suggested Reading

Kabbalah in 18th-Century Prague: A Response and Rejoinder

Sharron Flatto and Allan Nadler exchange views the Prague golem, Kabbalah, and Ezeliel Landau.

Who Is Man?

Two new books on sin and temptation.

Re-Intoxicated by God

The way out is clearly marked: Intense Talmud study leads to intense study of science and philosophy. Spinoza was (in fact, sometimes still is) a crucial step along the path out.

Chaim Grade: A Testimony

Toward the end of his life, the talmudist Saul Lieberman published his only Yiddish essay, an appreciation for his friend, the novelist Chaim Grade, the great witness to a lost world. Translated and with an introduction by Allan Nadler.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In