Drowning in the Red Sea

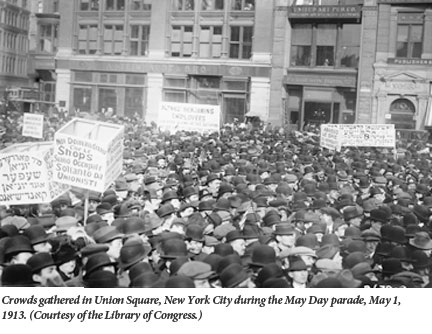

At the end of August 1929, after months of argument over Jewish access to the Western Wall, Arab riots began in Jerusalem and then spread to other parts of the country. The murder and maiming of over 400 Jews, most of them yeshiva students in Hebron and Safed, reminded Jewry both in Palestine and elsewhere of the Ukrainian pogroms a decade earlier. Jewish organizations throughout the world, including in America, began mobilizing what political protest they could on behalf of the Jews of Palestine, and the Yiddish press sprang into action.

The first response of the New York Communist Morgn Freiheit was only slightly more muted than that of other New York Yiddish dailies, the nominally Socialist Forverts, the moderately Zionist Morgn-Zhurnal, and the mildly traditional Tog. The Freiheit’s headlines on August 25 and 26 read: “20 Dead, 150 Wounded in Battles between Jews and Arabs in Jerusalem” and “Over 100 Dead in the Fighting in Palestine.” The paper’s editorials blamed the British for permitting Arab violence and failing to protect the Jewish victims. But the following day, in a dramatic reversal, the Freiheit redefined the murders as the start of an “Arab Revolt against England.”

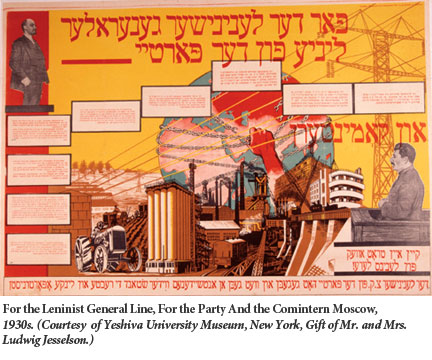

Now, according to the Freiheit, the Arabs were demanding an independent worker-and-peasant land for the masses, and were legitimately opposing the “Jewish fascists” who had provoked the riots. An editorial explained that whereas the Russian and Polish pogroms had targeted innocent Jews, this Arab uprising was provoked by Zionist imperialism: Arabs were said to have been victimized by Jews, just as the Jews had once been by the tsars. The new line had been dictated to the Freiheit by the Soviet Communist International, or Comintern.

The Comintern had been established in Moscow in 1919 to fight “by all available means, including armed force, for the overthrow of the international bourgeoisie and for the creation of an international Soviet republic as a transition stage to the complete abolition of the State.” Once the Bolshevik Revolution coalesced into the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) and Lenin established the dictatorship of the proletariat, the Communist Party functioned in all other countries as the instrument of a foreign state. Its exaggerated notions about the influence of world Jewry, perhaps fueled by Jews in the Party leadership, resulted in the establishment of the New York Yiddish Freiheit as one of the first Soviet-front agencies abroad.

The Freiheit‘s editorial attack on the Jews of Palestine outraged most of the American Yiddish readership. Some newsstand owners refused to carry the paper, and a special meeting of the American Yiddish Writers’ Association on September 11adopted resolutions condemning the Freiheit and expelling its associates for having desecrated “the most basic principles of professional ethics.” Several prominent contributors resigned in protest and the paper returned the favor by severing all ties with them.

The poet Jacob Glatstein, a regular columnist and editor of the Morgn-Zhurnal, wrote that the revulsion with the Freiheit was likely to mark the end of Communist influence among Jews in America. Yet since the paper claimed to be independent, Moscow was generally absolved from responsibility for the editorial change of heart. Thus, the Tog accepted in good faith its correspondent’s report from Moscow that everyone he spoke to “in communist circles” recognized that Arabs had launched bloody pogroms against innocent Jews with the collusion of anti-Semitic British officers. The Morgn-Zhurnal reported that the “official communist world greatly deplores the fallen Jews.” It was easier to blame the local editors, Shakhne Epstein and Moishe Olgin, for the Freiheit‘s sudden embrace of the Arabs than to wonder why they would have done so overnight.

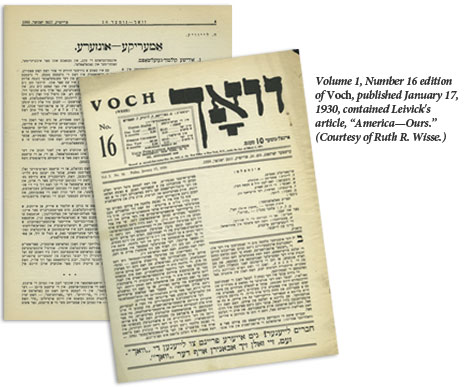

In this murky political atmosphere, a brilliant group of writers who had quit the Freiheit launched a dissident weekly, Voch, dedicated to “culture, literature, education, art, theater, music, and the like,” that steered a political course between the Freiheit and those whom the Freiheit opposed.

In accordance with their established tactics, they will push us to the Right. The other they will probably pull us and push us in the same direction. When we recall that among us nationalism too often goes along with Rightism, and Leftism with assimilation—our problems multiply because we are nationalists of the Left. But if we don’t “keep our heads” we will be of no use to anyone.

“Keeping our heads” was apparently conceived as an attempt to hold the middle ground between some claims of Jewishness and fealty to Communism, yet this editorial statement betrays the precariousness of the project. Unlike their colleagues in the Soviet Union who were feeling irresistible pressure to conform to the Comintern party line, the writers of Voch were free to define their own political loyalties, which left them exposed to both warring sides.

One might have thought that having quit the Freiheit out of sympathy with their fellow Jews in Palestine, the editors, H. Leivick, Menahem Boreisho, and Lamed Shapiro, would have followed this up with further interest in the fate of the Yishuv (as the Jewish community in Palestine was called). Rather, the opposite: Having demonstrated their “nationalism” by quitting the Freiheit, they felt obliged to prove their internationalist Leftist credentials. While acknowledging the unity of the Jewish people, they emphasized their solidarity with the working class that would become, if it had not already become, the carrier of their national values. Furthermore:

We consider the October Revolution to be the greatest event of recent generations. By transferring power to the workers, the Revolution simultaneously liberated national minorities, ensured their independence and undertook to help develop their cultures. We stand with the Soviet Union in its overall socialist development and in the economic and cultural reconstruction of Jewish life that the Soviet Union has undertaken.

As for Voch‘s national platform, it was: “We are Yidishistish, i.e. we stand for the development of Jewish life along secular modern lines.” Yiddish literature would draw together Jews in all countries, and Yiddish education would prepare the Jewish child for his later active role in the liberation of all workers and all nations. “[In] order that the child should grow into a complete person in his later battles, he must first receive background in universal ideas that are rooted in his own culture.” Thus Yiddish culture was to be the medium of spreading Communism rather than the other way around.

The contributors to Voch, including some of the leading American Yiddish writers of the day—Aron Leyeles, Leib Feinberg, Efraim Auerbach, Isaac Raboy, Moishe Leib Halpern, and Avrom Reisen—did not speak with a single voice, but many of their submissions showed the same need for Leftist self-justification. “We have absolutely not become Zionists because of the Palestinian tragedy,” insists Aron Leyeles, calling the Arab riots a “deserved blow” to Zionism for having trusted in the Balfour Declaration, and objecting only to the way the Freiheit had joyfully danced on Jewish graves. Lamed Shapiro concurred: “If it were possible, we have become even greater enemies of political Zionism than before.”

Nonetheless, the question of Palestine vexed Shapiro, he wrote, like a pinched toe that thinks it is the central organism of the body:

I know I don’t want to go to Palestine, so I say—I am against Palestine. I believe Yiddish is our language, so I decide—I am against Hebrew. When the Jewish Yishuv in Palestine is pogromized, I raise a hue and cry. This means I am not against Palestine. When Hebrew is persecuted in the Soviet Union-if it is persecuted there-I protest. So I am no longer against Hebrew. Where then am I?

In fact, Shapiro had once explored the possibility of joining his friend, the Hebrew writer Yosef Haim Brenner, in Palestine, and the bewilderment he voices here has deep psychological sources that were by then manifest in the chaotic circumstances of his life.

Shapiro’s fellow editor H. Leivick wielded special moral authority in the Yiddish literary world as an escaped prisoner from a term of life imprisonment in Siberia for his socialist conspiratorial work in pre-revolutionary Russia. After his daring escape, he had made his way to America, and soon began attracting notice for his autobiographical poetry that projected a Jewish and socialist man of conscience. When Leivick revisited his homeland, by then the Soviet Union, in 1925, some of the Yiddish writers he befriended there hoped that he would stay, and tried to convince him that this could benefit both him and the Soviet cause.

Although he did not stay, and broke with the Comintern four years later, Leivick was still loyal to revolutionary ideals. In “Why We Left the Freiheit,” he was unable to condemn Arab terror outright, since Bolshevism likewise justifies the use of terror. Instead, he tries to distinguish between a revolution that is waged in the name of historical necessity and an uprising that is bloodthirsty and sadistic, hailing as the “true” revolutionary someone who considers tragic the blood he must shed in its name.

On the same grounds, Leivick tries to exonerate Communism from the sins of the Freiheit by recalling a comparable disgrace: when certain revolutionaries of the 1880s had justified the pogroms in Russia as the beginnings of a proletarian revolt. Then as now, some Jewish radicals had called for revolution, promoting class warfare through the agency of pogroms. Although that proclamation was repressed, Leivick deemed it a scar in the history of revolution, to which the Freiheit had added another. “We consider the deeds of the Freiheit in these sad days a greater catastrophe in our lives than the catastrophe of the pogroms themselves.”—The emphasis was his.

The self-justification that Leivick offered for having left the Freiheit included his readiness to practice deceit on behalf of the Soviet system. He writes that on his 1925 visit to the Soviet Union he had seen so many “déclassé” Jews who had been devastated and brought to ruin, so many of whom were dying, that “ten Palestine pogroms are a joke compared to their downfall.” He witnessed the hunger and misery of many Jewish towns, including his own. “Had I let loose my so-many-times-suppressed pintele yid [Jewish spark], I would have had to raise a howl ten times greater than this one.” Yet he raised no cry. He differentiates himself from the Freiheit by boasting that he did not gloat over Jewish distress as the editors would have done. Even when he saw the condition of his uncle, once a wealthy manufacturer who was now expiring in a dank cellar, his cry “tore my heart—but did not embitter me, and did not turn me against the greatness, the greatness that is transpiring in the land of the Soviets.”

Writing from Berlin, the Yiddish novelist David Bergelson found Leivick tortured.

He has placed himself, as if deliberately, where the crosswinds will assail him from every side. Anyone else would be blown off his feet, but Leivick with his honesty and purity can dig in and hold that position for the rest of his life, pale and tight-lipped, a monument of defiance, resisting all those who allow themselves . . . to compromise.

Bergelson’s advice was for Leivick to drop the political side of Voch and make it a strictly literary magazine. But between the crosswinds was just where the paper wanted to be, responding on a weekly basis to events in the Soviet Union, trying to protect the ideal of revolutionary Communism from its supposedly mistaken representation in the Freiheit and elsewhere without ever yielding to what it called the nationalist “Right.”

Though the editorial policy of the paper remained steady, it did not impose strict discipline. Three pages of editorial commentary on current events were followed by another thirteen with a variety of poems, short fiction, feuilletons, political commentary, book or theater reviews, and a chronicle of current events, mostly about culture. Coverage of world events concerning Jews was delivered in the intimate Yiddish press style that assumed familiarity with all relevant terms and issues. Advertisements for such Leftist institutions as Camp Boiberik, Arbeter Ring (Workmen’s Circle), the American-Russian Travel Agency, gave it the flavor of a house organ, and professionals who advertised in the paper were advertising their politics along with their trade. Recurrent subjects were Yiddish schooling in Poland and America, support for Yiddish in all its manifestations, and local struggles over the direction of relief funds. The claims of Jewish national survival were in perpetual conflict with Soviet priorities. Since many Jews by then were growing wary of Communist takeovers in unions and Jewish organizational life, Voch tried to bolster faith in the Soviet model.

One hub of this controversy was Birobidzhan, the territory near the border with China designated by the Soviet rulers to serve as an autonomous Jewish region, an alternative to the Land of Israel, with Yiddish rather than Hebrew as its unifying language, and a secular culture shorn of its religious roots. Voch fully supported Birobidzhan, but objected when the Jewish section of the Communist Party, the Yevsektsia, deliberately scheduled Collectivization Day to coincide with Yom Kippur. Pyotr Smidovitch, administrator of Birobidzhan—whom the editors mistook for a Gentile—won high praise from Voch for declaring that Jews may fast and pray according to their customs. Yet when a correspondent in the Zionist Yiddish Tog made the same point, Voch felt obliged to clarify its political allegiances:

[If] with a knife at our throat, we were forced to choose: you [the Tog] and yours or the Yevsektn—we will choose the Yevsektn. Not because they please us—they don’t. But they are young and behind them there stands a great and fruitful idea. If they are blind in certain respects, they might in time begin to see . . . they have the potential. Your camp is the generation of the desert, in every respect. It is perhaps brutal to say so, but in all candor, your time has passed forever.

In short, Birobidzhan is the future; Eretz Yisroel, the past.

Halfway through what was to be the life of Voch, in the issue dated January 17, 1930, Leivick published “America—Ours,” a title uncharacteristic for the weekly. Previous issues had been far more interested in developments in Russia, including articles on the deteriorating shtetl, than in anybody’s America. Voch evinced no curiosity in such distinctively American subjects as subways and Indians and skyscrapers and Negroes, all of which had marked an earlier phase of American Yiddish writing. Nor was it interested in the currently falling stock market or failing banks. Governmental policies and affairs on the local or national level went simply unmentioned. And indeed, Leivick appeared to declare America “ours” mostly in condemnation of its faltering Jewish spiritual life, the dullness of its institutions, and the failure of visionary leadership in the Yiddish press, the workers’ movement, and communal organizations. As antidote, he hailed the recent establishment in New York of the Leftist Yiddishe kultur gezelshaft, the Organization for Yiddish Culture. The flag of Yiddish in America must be raised aloft, Leivick wrote, on a foundation of “unswerving revolutionary Yidishism.”

This worm’s eye view of the American Jewish community unwittingly illustrates Voch‘s own failure to appreciate the opportunities with which it had been blessed. “Unswerving revolutionary Yidishism” turned out in practice to mean an adversarial relationship to America as well as to Zionism, a self-ghettoization in the name of a broader internationalism, and commitment to a culture of self-deception. Indeed, within fifteen years, no one was more eager to expunge this chapter from American Jewish history than those who had written it. Though the mainstays of Voch remained partisan Leftists until World War II, in its aftermath they ignored this evidence of their former pro-Soviet phase as eagerly as Soviet writers were eliminating traces of their right-wing deviationism.

Apart from its cautionary value, Voch remains valuable to students of literature as a rare publishing outlet for rapidly declining Yiddish in America. Lamed Shapiro, for example, who never realized his full literary potential, published two stories in Voch—“Nesiye durkhn milkhveg” (Journey Through the Milky Way) and “Nyuyorkish” (New Yorkish)—that show his readiness for the first time to take on America as a subject. “Journey through the Milky Way” is a parable about waxing fat in America. A young Jew arrives at the turn of the century as part of the great Jewish immigration and begins a climb to riches in the women’s clothing trade, rising to the position of manufacturing boss—a synoptic version of Abraham Cahan’s The Rise of David Levinsky. The story charts the immigrant’s financial advancement through the rise in his weight, so that the more he eats the hungrier he grows. Diabetes is diagnosed as he tries to break the back of his factory’s union. By the time he yields to the workers, his body has begun to fail him and his girth to decline. In his final coma, he drifts into the weightless universe that has all along in the story been the counterpoint to this one, breaking through to the Milky Way and flying so far into distant space that he can no longer find his way back. Shapiro anticipates Nathanael West’s phantasmagoric visions of America, rendered here with a touch of humor. “New Yorkish,” a more substantial work, tries to capture with cinematographic delicacy the estrangement of a Jewish bachelor from the land of plenty. It is included in the Yale University Press New Yiddish Library Series’ recent edition of Shapiro’s The Cross and Other Jewish Stories.

I came upon Voch when I was tracking the literary career of Moishe Leib Halpern, who likewise found there a temporary outlet for his writing. Halpern had quit the Freiheit three years before the 1929 crisis, leaving him without any regular income, place to publish, or sustaining public. Voch put Halpern back on the road. He appeared in Philadelphia and Boston, where the paper was trying to establish cultural circles that would also provide financial support. Although some of Halpern’s contributions to Voch are marked by typical sourness toward America and Zionism, he seems to be having more fun than the others in unmasking local folly and corruption. To demonstrate the powerlessness of the language to which he is condemned, he describes a holdup, a police command, and a marriage proposal, which all fail because they were cast in Yiddish. Halpern quotes someone’s uncle saying that if he were a diplomat he would demand that all declarations of war henceforth be issued in “Zhargon”—in Yiddish—thereby guaranteeing world peace.

The poems Halpern published in Voch range from rakish and tender love lyrics to “Salute,” a satiric depiction of racist lynching as a patriotic American pastime. In John Hollander’s witty translation, Halpern writes:

There’s always something in our land, too,

And where there’s no lamppost that will do,

There’s a convenient tree: what’s clear’s

That a Black of at least twenty years

Hates anything tall that, in a pinch,

Would hold you high enough to lynch.

Although the one that I saw get

Hanged, wasn’t quite fifteen yet.

Sanctioned by a priest, the lynching is cheered by a maddened crowd within which the poet unaccountably situates himself—

. . . the whole world’s sorrow-stink

Who stood at a distance there to think—

Playing pocket pool, with your fingers curled—

To dream up a poem for yourself and the world.

Halpern had published his share of protest poems in the Freiheit, but less and less had they satisfied the taste of its editors. American capitalism was for him only one of many evils; artists and writers generated their own forms of corruption that were no less in need of deflation. The loathsome scene of lynching that Halpern fashions is made up entirely of stereotypes, and it is this sense of “saluting” his subject that turns the poet against himself. He registers the irrelevance of art to political action and of political indignation to art. While others in Voch wrote as if their opinions mattered and took pride in the pacific nature of Yidishism, Halpern exposed its weakness—and his own.

Voch was not about to take up Bergelson’s suggestion that it confine itself to literature and cultural issues, yet its growing roster of poets and writers hints at how much more Yiddish writing there might have been in America had it enjoyed a more robust publishing base. Peretz Hirschbein and Esther Shumiatcher, Kadya Molodowsky, and Malka Lee were among its contributors. One of the last issues included a poem by Itsik Manger of Warsaw. The tribulations of American Yiddish literature are poignantly registered in the ratio of Voch‘s contributors to the space available to them.

Even that did not last long; the periodical survived only 33 issues, until May 16, 1930. Nonetheless, though it may seem no more than a footnote in Jewish literary history, it ought to loom large for those who want to understand the development of Yiddish literature and culture, the history of American Jewry, and the role of Communism in the life of intellectuals.

Most representations of Jews and American Communism, whether in dramatic productions like “Angels in America” or as part of academic Cold War studies, have focused on the execution of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg and the prosecution of Communists by Senator Joseph McCarthy and the House Un-American Activities Committee. This excessive attention to the reaction or overreaction to the phenomenon leaves the impression that one is afraid to examine the phenomenon itself—namely, the involvement of many Jews with Communism in the process of their Americanization. Yet the Communist Party in America did rest largely on a Jewish base, and there are compelling reasons to study this segment of American and American Jewish history, not least because of the creative energy that went into it and the creative talent that it conscripted.

Though the vast majority of American Jews were either hostile or indifferent to Communism, with some in the forefront of the democratic opposition, it had enormous appeal to writers and intellectuals. Writing after World War II, the cultural critic Robert Warshow described the 1930s as a time in America “when virtually all intellectual vitality was derived in one way or another from the Communist party. If you were not somewhere within the party’s wide orbit, then you were likely to be in the opposition, which meant that much of your thought and energy had to be devoted to maintaining yourself in opposition. In either case, it was the Communist party that ultimately determined what you were to think about and in what terms.” Warshow’s impression of his circle of New York Intellectuals was even truer of the American Yiddish writers and intellectuals of the 1920s, some of whom had themselves escaped from tsarist conscription or imprisonment and welcomed Bolshevism as a form of redemption.

The brief history of Voch shows what moral credit Yiddish writers like Shapiro, Leivick, and Leyeles—writers of the highest order—were prepared to extend to the Soviet Union, even after ostensibly declaring their independence from it. One wishes that they had eventually undertaken their own self-accounting, whether in the form of khezhb’n hane’fesh (personal account of the soul) that Judaism considers indispensable to the moral life, or objectively, to help us better understand this phase of cultural history. For if Yiddish literature was the most pro-Soviet in the 1920s, its writers were the most cruelly betrayed in the following decades, and we would have benefited from knowing how participants in the travesty understood their role.

It did not happen. The enormity of the khurbn—the Yiddish term for the Holocaust is the same as that for the destructions of the Temple in Jerusalem—swept away their native communities and turned them into mourners, avelim. This was followed by Stalin’s execution of the members of the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee, which included the major Soviet Yiddish writers and intellectuals. The foundations of Yiddish were annihilated with its speakers. American Yiddish writers found what comfort they could in emergent Israel, which gathered up the surviving remnant. Smarting a little from Israel’s emphasis on Hebrew that came largely at the expense of their literary language, those writers who visited Israel were warmly received, and became contributors to Di goldene keyt, the Yiddish postwar quarterly established in Tel Aviv.

Its former enthusiasts had no wish to return imaginatively to what others have called “the romance with Communism.” But that they were spared their own intellectual and moral reckoning is all the more reason for their readers to undertake what they could not.

Suggested Reading

Letters, Spring 2023

Cliff-Hangers When I first read Hillel Halkin’s assertion in “On That Distant Day” (Winter 2023) that “for years now, Israel has seemed to me like a man sleepwalking toward a cliff” and “now we’ve fallen from it,” I thought it was excessive, though I shared his concerns about the Likud’s coalition partners (Zionist theocrats, anti-Zionist free-riders). Writing now, in the…

Letters, Fall 2020

The Coffee a Good Schmooze Demands, Unjustified Resentment, Whose True Voice?, and Yesterday's Today

Moses and Hellenism

In a provocative new work recently published in German, Bernd Witte proposes nothing less than an “alternative history of German culture,” as the subtitle of his finely wrought work of scholarship tells us. Moses and Homer: Greeks, Jews, Germans is a historical and cultural argument animated by powerful indignation. This history, he insists, has yet to be fully confronted.

Something Antigonus Said

When the Saducees misinterpreted Antigonus of Sokho, they lost eternity--at least that's what the Rabbis thought.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In