Black September

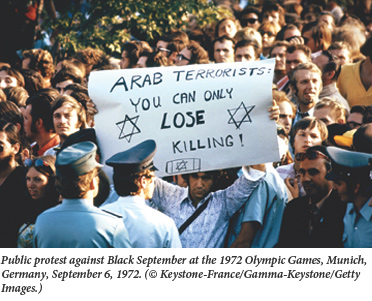

This summer, a campaign to convince the International Olympic Committee (IOC) to dedicate “Just One Minute” of the opening ceremonies of the 2012 London Olympics to the memory of the eleven Israeli athletes murdered forty years ago went viral. There were YouTube videos, a Twitter hashtag, a Facebook page, and an online petition, not to speak of statements of support from President Barack Obama and sportscaster Bob Costas. But the IOC resisted. Throughout those weeks as I signed the petition, “liked” the Facebook page, followed the hashtag, watched the videos, and wondered at the IOC’s opposition, I was also reading David Clay Large’s outstanding new book, Munich 1972: Tragedy, Terror, and Triumph at the Olympic Games.

Large, who earlier wrote a book on the infamous 1936 Berlin Olympics, emphasizes the extent to which the organizers’ determination to avoid recalling the then-recent Nazi past shaped the way they planned the 1972 Olympic Games and inadvertently facilitated what is remembered as the Munich massacre. Large describes the episode that began in the early morning hours on September 5:

Eight heavily armed men climbed over the unguarded fence surrounding the Olympic Village to gain access to the Israeli compound. The operation was carried out by “Black September,” an arm of the Palestine Liberation Organization’s Fatah group. In the course of seizing and confining a group of hostages, the Palestinians killed two Israelis. Now television coverage from Munich alternated between the athletic events-amazingly, these were not suspended until seven hours after the attack had begun-and hooded gunmen holding an unspecified number of Israeli Olympians captive in the team’s two-story compound at the Village. On the following morning, TV coverage switched to a grim-faced Bavarian official announcing that an attempt to rescue the remaining hostages at a nearby airfield called Fürstenfeldbruck had gone terribly awry and resulted in fifteen deaths-all nine of the hostages, five of the eight terrorists, and one German policeman.

This crisp, horrifying recap takes place early in the book, before Large turns to his meticulous reconstruction of the tragedy. Three chapters provide the history of the IOC’s decision to award the 1972 Games to Munich; the subsequent planning and building (and massive cost overruns) for those Games; and the obstacles to staging a happy, fun-filled Olympics in the Europe of the late 1960s and early 1970s. Although Large’s narrative recalls the athletic “triumphs” promised in the subtitle of Munich 1972 (even beyond Mark Spitz’s seven gold medals in swimming), the tragedy overwhelmed them, while undermining the West German planners’ aim to create a new image for Germany. Even the color scheme, the planners thought, would distance Munich from its country’s unpleasant recent past. Unlike some of his colleagues, Large notes, the man charged with these Games’ aesthetic design, Otl Aicher, possessed a more “honorable” background when it came to the Hitler era. But he, too, had a political agenda for Munich ’72:

Aicher summarily decreed that there must be no red, black, gold, or purple at Munich because these were the favored colors of dictatorships, old and new, as well as signifiers of German nationalism, past and present.

But the baby blue polyester uniforms he insisted on were not unproblematic: “who could take seriously security men who were dead ringers for vacationing seniors from Cleveland, Ohio?” Sadly, as the book makes all too clear, this was the least of the security problems. Large writes:

Although the killers were not German, the fact that the murders had taken place on German soil seemed to compound the horror—as did the peaceful setting: an Olympic festival designed to promote international brotherhood and understanding. Added to the horror was a bitter irony: the very effort to make Munich ’72 so different from Berlin ’36, and thereby replace ugly associations with positive ones, seemed to have helped facilitate a brutal terrorist attack whose outcome ended up rekindling memories of the bad old days. One can certainly say that, within the context of modern German history, and modern sports history, no road to hell was ever paved with nobler intentions.

Some of the details Large recovers are simply alluring trivia: Who knows (or remembers) that when the IOC convened in late April 1966 to select the host city for the 1972 Summer Games, the three other locations still in contention were Montreal, Madrid, and . . . Detroit? Who pauses to consider that the IOC simultaneously awarded the 1972 Winter Games to Sapporo, Japan, meaning that “roughly two decades after the end of World War II, the IOC had entrusted the world’s most prestigious international athletic festival to the losers in the epochal conflict.”

But Munich 1972 reminds us of other, more essential circumstances. The temporal proximity of those Summer Games to the Nazi era meant that the personal histories of some of the Germans most involved with the initial bid and ultimate planning were not exactly untarnished. A 21st—century reader may find it difficult to understand how someone such as Wilhelm “Willi” Daume, whose resume included service in the Wehrmacht, the Nazi Party, and the SD (the security organization of the SS) managed to downplay that history and ultimately steer the ship that brought the Olympic Games to Munich. But Large explains: “Even if Daume had not been able to reinvent himself as an opponent of National Socialism, his actual service to the Hitler State would not have been too great a liability in an era when Soviet Communism, not vanquished Nazism, was perceived as the primary threat to the Western world.” In fact, the book provides a useful crash course in Cold War history, especially through the lens of the fraught relations between East and West Germany.

Large has turned up fascinating material in his archival research. In a haunting passage he reviews a risk analysis commissioned by Manfred Schreiber, Munich’s police chief and head of security for the Games. The police psychologist who produced this list of twenty-six worst-case scenarios, Georg Sieber, was, in Large’s words, “a serious student of global terrorist activities” who envisioned a series of potential threats in keeping with the times, with Irish Republican Army (IRA) attacks and Basque separatist activity among them. Eerily, Sieber’s twenty-first scenario described “twelve armed Palestinian commandos scaling the perimeter of the Olympic Village, invading the Israeli team compound, taking a number of hostages, and threatening to kill those hostages unless Arab political prisoners were freed from Israeli jails and the Palestinian commandos flown to safety in some friendly Arab capital.” Even if such an attack failed, Sieber warned, it would “make a bloody mess of the Munich Games.” But Schreiber found this and other scenarios far-fetched. As Large repeatedly emphasizes, the authorities behind the 1972 Munich Games envisioned a laid-back and convivial occasion that would bring positive worldwide attention to West Germany.

Sometimes lost in memories of the Munich massacre are the specifics of Black September’s stated objectives. Their initial demands, made known shortly after five a.m. on September 5, included the release of 236 individuals, mainly Palestinians held in Israeli prisons, such as the two surviving Black September commandos—women—who had hijacked a Sabena airlines flight en route to Tel Aviv earlier in the year. But they also demanded the release of Okamoto Kozo, a Japanese Red Army operative held in Israel in connection with a massacre at Lod Airport, along with the release from German prison of the recently captured Andreas Baader and Ulrike Meinhof, leaders of the violent radical leftist group that bore their names. The Black Septemberists threatened to kill one Israeli hostage every hour if their demands were not met.

As negotiation efforts ensued, the terrorist’s demands evolved. Meanwhile, a rescue attempt at the Olympic Village had to be scuttled when it was broadcast live as the Black Septemberists watched. Large provides a detailed account of how the hostage-takers and their captives ended up at Fürstenfeldbruck airfield, from which the Black Septemberists expected to be flown to Cairo to be reunited with the Arab prisoners whose freedom they had demanded. What the terrorists failed to realize was that their new demands allowed the German negotiators to change the center of action from the Olympic Village to the airfield, where an ambush was planned. Large’s account of how that plan unraveled, leading to the cornered terrorists’ murderous response, is difficult to read. (It must have been excruciating to write.)

Even before its gruesome denouement, there was disagreement about how the episode should be acknowledged. As noted, the Olympic competitions continued for many hours; it was not until nearly four p.m. that Daume announced the postponement of the rest of the day’s Olympic events. Aware at the time of only one Israeli death—in fact, two had been killed already—Daume also said that a memorial service would take place the next morning.

The disaster at the airfield made the memorial service even more essential. Yet again, there were missteps, including jarring comments from IOC president Avery Brundage, who described the terrorist action as one of “two savage attacks” against the games, the other being the successful political campaign to exclude Rhodesia. One day later—September 7—the Games resumed.

As Large demonstrates, that decision, though strongly backed by the IOC Executive Committee and many governments, was quite controversial. Athletes and their national Olympic Committees were divided; even the Israelis weren’t united in their reactions. Although Prime Minister Golda Meir ordered what remained of the Israeli team to return home at once, Large writes that the delegation’s chief, Shmuel Lalkin, “would have preferred to stay on and compete,” and cites race-walker Shaul Ladany, who argued that by leaving the Games the Israelis would be handing the terrorists yet another victory.

As the book closes, Large addresses issues of accountability, compensation, and commemoration. Early and often, the families of the murdered athletes asked the IOC to observe a minute of silence for the murdered Israelis at future Olympic opening ceremonies. Early and often, the IOC refused, although, as Lodge writes, “after twenty-four years of stonewalling, the IOC agreed to a rather low-key acknowledgment of the Munich murders by inviting children of the slain Israeli Olympians to attend the 1996 Atlanta Summer Games.” Appeals for a moment of silence have continued, and, as we know, the IOC has continued deny them.

Munich 1972 is a massively researched, eminently readable history. Although his prose is calm and his approach evenhanded, for most readers Large’s book will evoke astonishment, exasperation, and, finally, grief.

Suggested Reading

Screwball Tragedy

Picture a Jewish town, located deep in a Polish forest, that hasn’t received so much as a postcard from the outside world in more than a century. Max Gross conjured it up The Lost Shtetl: A Novel, and the result is both screwball and serious.

Daniel Bell (1919-2011)

In memoriam.

Lives in Translation

The elegant essays in Hillel Halkin's new book are the fruit of a lifetime devoted to Hebrew literature.

Jokes and Justice

We were sitting in our apartment one evening when a Spanish philosopher dropped in ...

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In