“With a Wolf in One Eye”: Sutzkever in Israel

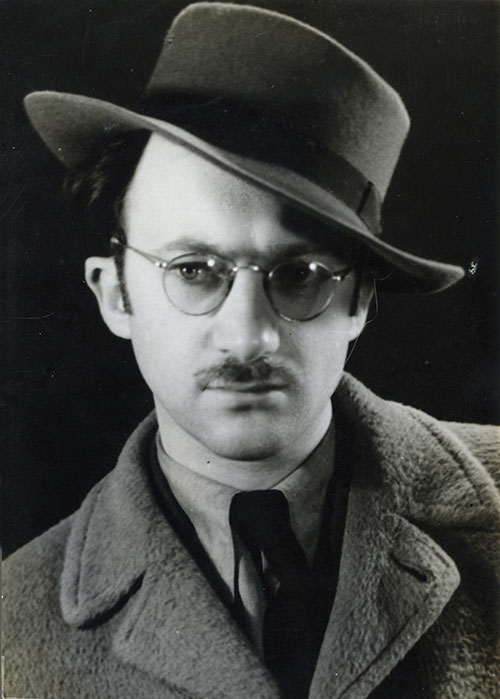

The most significant thing I accomplished in my two years as a press officer of the Canadian Jewish Congress (CJC) was to arrange the first North American speaking tour for the great Yiddish poet Abraham (Avrom) Sutzkever in the spring of 1959. I had met him two years earlier during the summer my husband and I spent in Israel, a meeting I have described in these pages. When Sutzkever wrote to me, saying that he wanted to come to Canada, I could not believe our luck.

Although I didn’t know it, Jewish organizations and well-connected officials in New York had been trying for years to arrange a speaking tour for Sutzkever in the United States. What I did know was that in 1959 the majority of Canada’s 250,000 Jews were still Yiddish speakers, and, among them, every literate person knew Sutzkever’s name. I was confident that these Yiddish readers would help me get the leadership of CJC to sponsor his appearances in Montreal, Toronto, and Winnipeg.

Sutzkever’s life had, to that point, merged, as though on a God-ordained path, with the fate of the Jewish people in the 20th century. Born in Smorgon, near Vilna, in 1913, the youngest of three children, he was taken by his refugee parents to Omsk at the outbreak of the First World War and returned to Vilna at its end by his widowed mother, his father having died in Siberia. He began writing poetry as part of a circle of writers and artists in interwar Vilna and published two volumes by the time the ghetto enclosed him with the rest of Vilna Jewry in 1941.

In the ghetto, under impossible conditions, he continued writing poems. With his wife Freydke, he joined underground efforts to smuggle in arms while directing cultural affairs that included performances of the ghetto theater, literary contests, and every kind of activity that could save lives or cultural treasures. The couple escaped before the ghetto’s liquidation to join partisans in the forests. From there, they were airlifted to Moscow in a plane sent expressly to bring the poet to the Soviet Union as a living emblem of the murdered Jews of Poland. In Moscow, he befriended Jewish writers and cultural leaders like the poet Peretz Markish, novelist David Bergelson, and famed director of the Moscow Theater, Solomon Mikhoels, before they were murdered on Stalin’s orders. After the war, he bore witness at the Nuremberg trials, and, returning to Vilna after its liberation, he helped to retrieve some of the materials they had buried to save from the Nazis. When he left the Soviet Union as a repatriated Pole in 1946, he departed for Paris and went from there to Palestine. Thanks to the intervention of Golda Meyerson—later Meir—he arrived in Tel Aviv in 1947, half a year before the establishment of the Jewish state.

These events and the power of his verse made him the most famous living poet in the Yiddish language. What is more, he exuded heroism—a force that needed no self-promotion or validation from others. Sutzkever knew that he had been born to be a mighty Yiddish poet, and, when history put him to a terrifying test, he met the challenge and became what he was meant to be.

His Canadian visit went beyond my expectations. The first evening in Montreal featured greetings from the poets Aaron Leyeles and I. I. Schwartz, who had come up from New York to embrace him, and from the local doyen of Yiddish literature, Melekh Ravitch. Other writers had come for the occasion, one from as far away as Mexico. The hall was packed, and people had to be turned away. Anticipating that his audiences would include many survivors of the war who would want to hear poems he had written in the ghetto, he read several that were already famous: the poem about the dwindling underground schoolroom of the teacher Mira and the one describing a wagon of shoes bound for Germany among which he recognizes his mother’s. But in smaller gatherings, including one at my parents’ home, he read more inward-looking poems that harkened back to his childhood in Siberia and his youth in Vilna. The loveliest of them breathed the air of Eretz Yisrael.

At that time, I was friends with Sam Gesser, the Montreal impresario who organized local folk music concerts and recorded them for Folkways Records. We arranged a studio session in which Sutzkever cut the record of his poetry that was later made available through the Smithsonian Institute. The first side featured poems of the ghetto, recited in the resounding Russian rhetorical style of Mayakovsky and Yevtushenko as befits a man addressing an audience of thousands. The Israeli-themed poems on the reverse side would have profited from a softer reading, but I was not about to offer any such suggestion. Maybe it’s just as well. That voice projected the potency of poetry and national survival, which were, for Sutzkever and his audiences, one and the same.

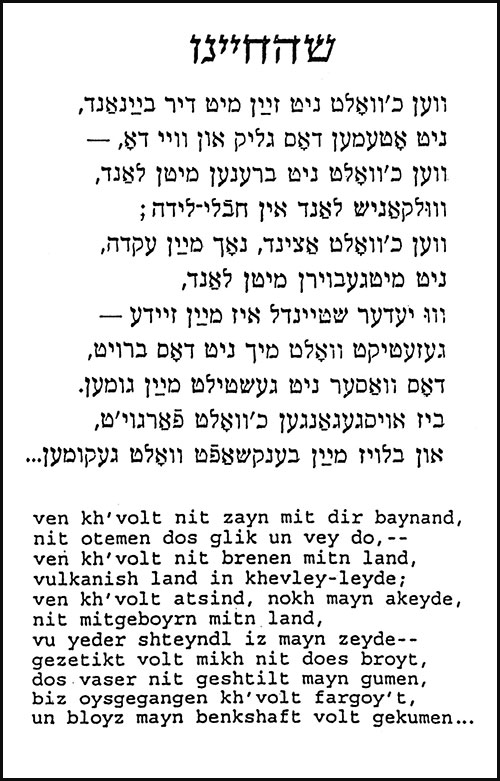

Of the works that Sutzkever read and recorded in Montreal, I was haunted by an untitled lyric that he dated 1947, shortly after he had arrived in Palestine. My translation is merely literal:

Were I not together with you,

Not breathing joy and pain here—

Were I not burning with the Land,

Volcanic Land in its birth-throes;

Were I now, after my akedah,

Not reborn with the Land,

Where every pebble is my zeyde—

Bread would not sate my hunger,

Water would not soothe my gums.

Till I would expire, turned Gentile,

And my longing would come on its own. . .

This poem was first published in the Yiddish paper issued and distributed for the displaced persons camps by the Yishuv in Palestine. It is hard to know what its earliest readers made of it. The weekly aimed at boosting morale and encouraging aliyah, but Sutzkever’s poem makes no concessions to clarity or message. It is written from the perspective of someone who has improbably reached his destination, and its ideas are so severely compressed that, after publishing an 11-page article about this poem some years ago, I still felt I had not begun to do it justice.

I now find myself turning to it again, this time as the opening lyric of In fayervogn (In the Chariot of Fire, 1952), Sutzkever’s first collection of poems written in Israel. There, it heads the section called Shehekhiyonu, the blessing Jews traditionally pronounce upon new experiences, including first reaching the Land of Israel. Addressed to an unnamed presence, this thanksgiving prayer replaces the tripartite thanks to God—“shehekhiyonu, who has granted us life, vekiymonu, sustained us, vehigiyonu lazman hazeh, and enabled us to reach this occasion”—with clauses beginning, “Were I not,” framing the speaker’s gratitude in his awareness that he has attained what was denied his murdered fellow Jews. The word “not”recurs six times in 11 lines, the likelihood of his not having arrived being so much greater than that of his being there. The original Shehekhiyonu prayer already blesses what cannot be taken for granted, but the odds here were so astronomically greater that the poem is written in contingent case, each segment citing what has been gained in terms of what might have been lost.

For this Jew, the joy and woe of national resurrection are forever fused. The poem invokes a country that is ablaze, fighting for its life. None of its images points to any specific event, yet Israel’s War of Independence was already raging when Sutzkever arrived with his wife and daughter, and the volcanic eruptions never ceased even after the birth of the state. Khevle-leyde, the Yiddish-Hebrew term he uses for the birth pangs of the country, is the same term used for the process that anticipates the coming of the messiah.

The third part of the blessing, “Who has enabled us to reach this occasion,” presents the poet with his greatest challenge. Commanded to sacrifice his son, the biblical Abraham was spared by the substitution of a ram, but the son born to Avrom and Freydke Sutzkever in a ghetto hospital was immediately put to death on Nazi orders. Sutzkever himself narrowly escaped death several times, but his mother was killed, and his Jewish Vilna would never, unlike Zion, rise from its ashes. Thus, to say, as he does here, that he has undergone the akedah is true—as both the sacrificing father and the all-but-sacrificed child.

The great stones of the Western Wall go unmentioned in this homecoming prayer; instead, the poet offers his thanks for every familial pebble of the soil underfoot. The Yiddish rhyme of akeyde with zeyde binds the biblical Hebrew to diaspora Yiddish. The linguist Uriel Weinreich drew attention to the way the rhyme scheme of this poem reinforces its subject by joining Hebrew with the several etymological components of Yiddish—zeyde from the Polish dziadzia (grandpa); khevle-leyde from the Talmud; and vey do (woe here), ingeniously, from German. Avoiding the readymade Zionist words like aliyah, Zion, or even Eretz Yisrael, Sutzkever uses the plain fare of Yiddish to bring us to the climactic word composed expressly for this occasion (perhaps cause for an artistic Shehekhiyonu).

Had he not reached the Land of Israel, the poet would have died fargoyt, a past participle that sounds as natural as the sun setting (we say di zun fargeyt) but defines a new kind of death: to turn goy. That word for turning Gentile is itself untranslatable. (“Gentiled” certainly wouldn’t do it.) When all is said and done, the danger is not murder at the hands of the Nazis or Soviets but extinction in a diaspora too long endured. There were Zionists who said there could be no future for Jews outside the Land of Israel. Though removed from such political rhetoric, this poem says that, without homecoming, there could have been no Jewish survival.

Sutzkever’s prayer of homecoming is in the tradition of the Jewish longing for Zion reaching all the way back to the psalmist who ached for Jerusalem by the rivers of Babylon and to Yehuda Halevi, the great 12th-century poet of Spain who followed his heart to the East. Halevi appears in a poem several pages later in the book. “On the sea / Between the death and birth of waves / You can feel his yearning.” It was imperative for Sutzkever that the return to the Land of Israel should not overlook the many millions of dispersed Jews who had guaranteed its recovery. Thus, the 11th line of the poem, “And my longing would come on its own . . . ” trails its apparent climax and carries a yearning even more powerful than its realization. But why end with the longing rather than with his presence? Does this favor the wish over its fulfillment? Is it, as the American Jewish writer Isaac Rosenfeld once suggested, that the longing for Jerusalem is actually not for the object of its desire but for the unsatisfied craving itself?

Rosenfeld’s is the kind of inversion encouraged by psychoanalysis that sees the negative as a photographer does in developing a picture. It is clever, and it may apply in some cases, but not here. The speaker uses yearning in the opposite way, to emphasize that, even had he died among Gentiles in Europe, his yearning would have arrived independently. This was not a hunger for hunger but a satisfaction that exceeds satiety. It is pronounced on behalf of the generations of Jews who knew that if they died in exile, they would return to the land, posthumously if necessary—the Jews who prepared a packet of earth from the Land of Israel to be buried with them, anticipating their resurrection and return with the coming of the messiah. More immediately, that final line represents the martyred Jews of Europe whose longing comes to nurture the country.

The tension in Judaism between living within and outside the Land of Israel begins with the first Abraham’s passage to Canaan. Our Avrom, who spent his childhood in Siberia, came to Israel from the opposite direction, from the land of snow, with no intention of erasing his formative past.

He had started out in his teens as a notoriously individualistic lyrical poet who defied the collectivist culture around him by sealing a partnership with the natural world, inviting the first star in the firmament to reflect his presence as a fellow newcomer, just as he was doing for it in his poem, and offering permanence to the Siberian snowman of his childhood who would otherwise melt. He cast himself as a fellow creator, ascribing supreme power to poetry not by lowering the transcendent standard but by aspiring to it. When some friends wondered how such a rarified poet could continue writing in the conditions of the ghetto, he turned the question inside out: only the poet with absolute faith in himself and in poetry could hope to withstand the degradation.

The ghetto recognized no individuals and humiliated them indiscriminately. Even as Sutzkever recorded the details of that humiliation, the flow of his poetry strengthened his confidence, and that confidence sustained others around him. His singularity became inseparable from that of the Jew; the heroic image ascribed to him in the ghetto and its aftermath confirmed the person he had become. He absorbed the national fate as organically as roots absorb moisture, and Yiddish, the substance of his poetry, thrived with him. After the war, he addressed the national fate in three epic works: a farewell to Poland (Tsu poyln), the saga of Jews in hiding in the Vilna sewers (Geheymshtot), and the shipboard record of survivors who sail for the spiritual soil of the Jewish homeland (Gaystike erd).

But his favored form remained the lyric, and now, having perhaps fulfilled his obligation to history, he was free to speak more personally. With an entirely new landscape before him, he could acquaint himself with every pebble and wadi. He could also assume prophetic responsibility for the great drama in which he had been cast. This would mean striking a balance among his duties to the dead who were left without a voice, to this welcoming haven and those laying down their lives for it, and to the private poetic insight that he had suppressed for a decade.

His newfound freedom also had its drawbacks. Whereas Sutzkever had not been able to extricate himself from the national fate in Vilna, in Moscow, or among the Jewish refugees in Paris, he was now out of the mainstream. His fellow immigrants were intent on adapting to the new conditions and perhaps trying to make up for the part of their lives that had been taken from them. Jews of the Yishuv urgently needed to secure the country, freeing themselves from the British, staving off Arab attacks, starting up an economy, creating the infrastructure for self-government, feeding and clothing the population, and beginning to integrate the refugees. Except for personal losses, they could not pause to mourn. The poets of Israel were also preoccupied with the tasks before them, and even those who dealt with the khurbn did so from a distance. Their poems, too, combined pain and joy, but theirs was the loss of soldiers in battle, of civilians securing their state.

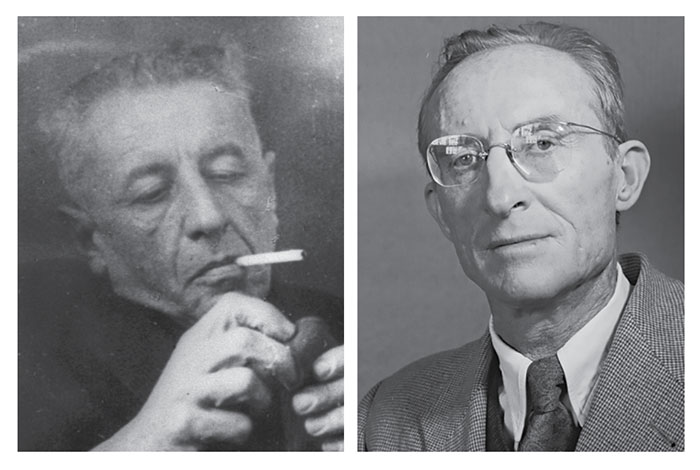

“Uri Tzvi Greenberg and [Natan] Alterman are the best,” was how Sutzkever sized up the current crop of Israeli poets four months after arriving in Tel Aviv. Writing to his fellow Vilna poet Chaim Grade, who had settled in New York, Sutzkever confided as one craftsman to another that he found the younger Israeli poets “very uninteresting” because they lacked the dense texture of European and traditional Hebrew sources. “I often think that only a Yiddish poet will truly celebrate Eretz Yisrael. Because the old-new Yiddish language is more Tanakhic than present-day Hebrew speech that is emptied of all Yerusholayims.” In Czernowitz, Jews had created Jerusalem on the Prut; in Toledo, the Jerusalem of Spain; and, incomparably, in Vilna, the Jerusalem of Lithuania. And while Hebrew had not yet absorbed the richness of those centuries of exile, Yiddish had achieved astonishing ripeness as the repository of eight hundred years of European Jewish life, capped by the last two centuries of dynamic Yiddish folk and individual creativity. That two poets as distinctive as he and Grade should have emerged from the same small literary circle of Vilna was proof enough of Sutzkever’s contention that only the Yiddish poet could do justice to the historic transition from exile to homeland. A poet is only as good as his or her instrument, and, at that juncture in Jewish history, he and Grade had the Stradivarii. And Sutzkever was in Israel.

But even he could not create in a vacuum. Ben-Gurion’s government had mandated the formal use of Hebrew over Yiddish as the only way of consolidating the Jewish state. Most of Tel Aviv was then still Yiddish speaking, and this included people prominent in politics, culture, and the arts who went along with the policy, either in active agreement or as an unwelcome necessity. Though Sutzkever was accorded a warm personal welcome in the literary cafés, he was not prepared to live as a guest at someone else’s table. At this point, he accomplished what some considered his greatest miracle. Unlike those Yiddish writers in Israel and abroad who merely complained of the insult being done to their mame-loshn, their mother tongue, he set about creating the literary culture he needed under the aegis of the very government that was enforcing the use of Hebrew.

Sutzkever was helped by Zalman Shazar, himself a Hebrew poet and great lover of Yiddish who was also editor of the newspaper Davar and influential member of the Histadrut, the all-important General Organization of Workers. The newcomer sought the help of supporters of Yiddish in Paris and New York, but it was the improbable support of the Histadrut that provided the office and basic support necessary for the establishment of his Yiddish quarterly. Sutzkever named it Di goldene keyt for the “golden chain” of Jewish tradition, echoing the title of Peretz’s poetic drama.

Di goldene keyt became the central address for the best Yiddish writing around the world. Sutzkever hosted the visits of Yiddish writers from abroad and promoted the journal on his visits to the major Jewish centers in Africa and the Americas. He sponsored literary awards and literary events and inspired younger writers to write in Yiddish and others to return to the language. He published his own poetry in every issue. These poems were both an extension of Sutzkever’s earlier writing and a departure from it with new rhymes and subjects and a biblical vocabulary that had never before figured in his work.

In fayervogn is the collection of the poems Sutzkever wrote during his first five years in Israel, 1947–1951, arranged thematically to map his encounter with the country. Following his Shehekhiyonu comes the most explicit summons in all his writing:

You arrived naked

Wholly aflame.

Your clothes—

Stitched by motherly fingers,

As if playing piano on velvet and silk—fell scorched into darkness.

You salvaged the needles.

(For “stitched,” Sutzkever created the word genodlt, whose English equivalent, “needled,” has acquired another meaning.)

Addressed in prophetic mode, the poet is charred by the Holocaust but intact “with a wolf in one eye and in the other—your mother.” These opposites cannot be separated: “Vest zey shoyn beydn / nit konen tsesheydn.” Rhyme in Sutzkever often performs the task it does here of indissolubly joining apparent opposites. Much of Judaism calls for strict distinctions to be observed between the sacred and the profane, and, while Sutzkever never blurs the boundaries between good and evil, he has acquired a doubled vision that will not allow him to separate wolf from mother or the khurbn in Europe from the rebirth of Israel. Unlike so much other modern writing, Sutzkever creates these improbable pairings not for the sake of paradox or irony but as a matter of complex fact. The fire that consumed Europe’s Jews and left him naked is the prophesied chariot of fire restoring Jewish life to the homeland.

The wolf in his eye is the raw animal knowledge he was forced to acquire to offset Vilna’s tender legacy. Here, I paraphrase the rest of the summons:

Even had you been greeted by Isaiah, he would have offered his prophecies with lowered leaden eyelids and shamed lips. Don’t look for consolation from even your own brother. Between the two of you there lies a Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, like an ever-flaming River Sambation, that tosses Jewish fate around even on the Sabbath. How can the people here believe that you in Warsaw were protecting the Kastel? That you in the kingdom of death forged this lively-homey young state? You will be believed by the volcanic heartbeat of this land that you heard when YOUR heart stopped beating temporarily. . . . That voice, speaking in the language of the Yiddish Pentateuch, will say—You are mine, may you be blessed in your coming. My sheep—are yours, my garden—yours; now plant your vineyard as tenderly as you once savagely fired your rifle.

Isaiah’s prophecy, read on the Sabbath of Consolation after extended annual mourning for the fall of Jerusalem, promises Jews that their “iniquity” has been expiated. It might seem only natural to turn to such passages in what appears to be the fulfillment of the biblical prophecy, but the poet expects no such consolation, for how can that prophet look this survivor in the eye? It would be the ugliest blasphemy to accept Israel’s rebirth as national recompense for the khurbn, yet even worse to suggest that Jewish survival had not been worth the cost.

This poem, dated 1948, was written after soldiers of the Palmach, in one of the bloodiest battles of the fight for independence, had finally captured the fortifications on the Kastel, the hill that commanded the road from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem. No Israeli brother (Sutzkever’s real-life brother Moshe, who came to Jerusalem in the 1930s, was an engineer engaged in building the country) can be expected to appreciate that the resistance of European Jews was the same driving force that opened the road to Jerusalem. The legendary ever-roiling River Sambation that once separated Jews from the lost tribes of Israel still divides immigrant from resident.

This was the mood of the country. “From the Tanakh to the Palmach”—leapfrogging the intervening millennia—was David Ben-Gurion’s idea of Jewish continuity, and not his alone. The plan for opening the road to Jerusalem was called “Operation Nachshon” after the biblical Nachshon ben Aminadav, who, according to a famous midrash, was the first to jump into the sea when the Jews fled Egypt. Meanwhile, Sutzkever’s Vilna landsman, Yiddish and Hebrew poet Abba Kovner, had unwittingly reinforced the contrast between the Jews of exile and the new generation of fighters. In the Vilna Ghetto in 1942, once Kovner realized that the Germans intended to destroy them all, he called on his fellow Jews not to go “like sheep to the slaughter” and helped form a partisan unit. Arriving in Israel in 1947 and settling in a kibbutz, he and other ghetto fighters were seen as the heroes of Jewish armed resistance, and, though he insisted that the rest of the ghetto had not been passive, his phrase became a byword for Jewish submissiveness.

For this rebuff of exile, Sutzkever substitutes Di goldene keyt, his vision of uninterrupted Jewish creativity. Israel was being repopulated by Jews who had developed, in the centuries between the two Nachshons, a mighty civilization that included the incomparable richness of Yiddish. The Jews of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising were of the same mettle as those who fought at Kastel. Who else but these diaspora Jews had so courageously reclaimed the homeland? To the personal difficulty of balancing redemption and mourning and the theological disproportion between prophecy and fulfillment, Sutzkever adds the historical challenge of treasuring in Israel all that had been created in exile. The concluding lines of this summons reverse the usual contrast between soft diaspora Jew and hard-shelled sabra by pairing the akhzoryes of the poet’s rifle—savagery conveyed in its sound—with the tenderness of transplanting himself into this new home. The soil itself extends the comfort that is currently unavailable from God or his prophet.

Naturally, Israel’s jettisoning of Yiddish was a sore point since the life of a poet—more than that of any other native speaker—is invested in his or her language. Thus, in the book’s angriest poem, “Yiddish,” the poet asks the doomsayer precisely where he thinks Yiddish has “gone under.” “Maybe at the Western Wall? / If so, I shall come there, come / Open my mouth, / And like a lion / Garbed in fiery scarlet, / I shall swallow this tongue as it sets / And awaken all the generations with my roar!” Sutzkever could be fierce in defense of Yiddish, but the rest of the book demonstrates its power by what he does with this language.

A striking feature of the book is its missing part: the life the Sutzkevers were actually living in Tel Aviv, where they settled and raised their two daughters. Tel Aviv figures nowhere in the 92 longer and shorter poems. Freydke Sutzkever found it hard to accept the loss of her family and even harder to substitute the new Jewish society for the one she had lost. As poet and editor, Sutzkever was fully embedded in literary society and kept abreast of everything happening in local publishing, but the petty squabbles that consumed his correspondence were nowhere to be found in his verse. The poets he cites are mostly Middle Eastern. He seemed to find the cultural vocabulary he needed in the parallel experience of Sephardi Jews, whose heritage was even more marginal than his to the new state-in-the-making.

In Safed, he is bewitched by the mystical aura of the great kabbalist Isaac Luria and his disciple, the poet Israel ben Moses Najara, author of hundreds of poems and hymns. He senses in this city, which is “changeless as an apple,” the haunting presence of wandering minstrels stopping to hear Najara’s hymns, the most familiar of which, Ya ribon v’almayah (God, Sovereign of all worlds), still resounds every Sabbath. Another poem extols the three hundred donkeys it took to transport to the Land of Israel the poems of the Yemenite 17th-century poet Shalom Shabazi, whose descendants still sing them at their weddings. Alas, the donkeys bearing Sutzkever’sYiddish verses were not as successful. He grasped what has since become an obvious feature of modern Israel—namely, that the Jews of Arab lands carried on their traditions with much less ambivalence than European Jews, who had been affected by the Enlightenment. There was no counterpart among Sephardi Jews to the ideological embrace of modernity and abandonment of Yiddish.

In Lod, one of the biblical cities whose inhabitants returned from the Babylonian exile and which is now the site of Israel’s international airport, the poet welcomes a flight from Iraq, which he calls by its ancient name. Among those arriving and being greeted in 70 dialects is a blind old man who falls on his knees to kiss the ground but then cannot rise again. This returnee from Babylon calls over his granddaughter and, with what may be his last breath, asks her to see that he is buried in the land of Isaiah with the three stones he has brought with him in his abaya. In reversing the custom of Jews interred outside Israel who were buried with a token of its soil, Sutzkever underlines the necessity of incorporating the memories of the far-flung exile in the reclaimed land.

In Jerusalem, there is exaltation:

If, just once, you wish to see eternity face to face and maybe, not die—hide your eyes, turn them down like wicks in your skull. Then, self-igniting, go to the encounter your wandering has not warranted until now—and open them facing Jerusalem’s mirrors of stone.

Even in this prose rendition, the poem “Mirrors of Stone” (the Yiddish feldz is actually more rock than stone) suggests that the poet’s reach for the deathlessness he had once sought in nature is now invested in this historical landscape. The Jerusalem he sees is not the temporal seat of Jewish government, home of the fledgling Hebrew University and Hadassah hospital, not the intersection of three faiths. It is the eternal city, abode of the permanency he had been pursuing since he buried his father in Siberia at age seven. European Romantic poets reached for the sublime. Sutzkever reaches out to the subterranean streams under this city of David and to the mirroring presence of God.

The section of poems on Jerusalem includes yet another Sephardi source, this one invented. “The Testament of Nissim Laniado” professes to be a document the poet discovers in a corner of the religious quarter Meah Shearim and is inspired to translate into Yiddish. Although the entire poem is composed in stanzas of identical rhythm and rhyme, the diction turns plainer when it moves from the poet’s discovery of the document to Laniado’s will. Taking into account whatever conditions might then prevail upon his demise—war or truce, drought or fecundity—he asks to be buried upright in his holiday best so that, after his extended sleep, he should be ready to rejoin the life from which he is now temporarily suspended. This Jew has heard Isaiah’s call, and he plans to be ready and waiting when he hears, “Come: Let us go up to the Mount of the Lord, to the House of the God of Jacob.” Sutzkever, a consummate modern, does not issue that call in his own name but, rather, through this “accidentally discovered” document in a different Jewish language.

When I first read the Sephardi-themed poems of this book, I thought them part of Sutzkever’s attraction to the exotic, the same buoyant curiosity that drew him earlier to the Kyrgyz of Siberia and, a few years later, to the king of the Zulus when he visited the Jewish communities of Africa. But it is truer to see them as the vehicle for an expression of unmediated faith. Though both the poet and the Yiddish language were then at the peak of their powers, they were too burdened—in the poet’s own words, too “charred” for simple belief. One of Sutzkever’s favorite Yiddish poets was Yehoash (Solomon Blumgarten, 1872–1927), who visited Palestine in 1914 and translated the Hebrew Bible into Yiddish. This was the medium through which Sutzkever absorbed the Bible. Before the war, he had also begun to immerse himself in Old Yiddish texts, perhaps already searching for a liturgical register. Yehoash gave him a biblical Yiddish, but Sephardi poets offered the models of plainer devotion that inspired so much good in the country—and so much of the good that lay outside Tel Aviv.

Thus far, the poet’s responses were to Safed, Tiberias, Lod, and the holiness of Jerusalem. Heading south into the open desert was “where stillness wrestles with silence,” a place then still more resonant with echoes of the past than the drip of irrigation hoses or laughter of schoolchildren. He had no car and did not drive, so he could not have been traveling there alone, yet lone is how he figures in these poems, taking pure pleasure in his art, as he had done when he was starting out.

A sight-and-sound poem of 1947 says, “Hear the sound of boundless light, as dew falls in the valley: A crystal spring, and soft its sound”:

Farnem dos kol

Fun likht on tsol:

Dos falt der tal

Der tal

In tol.

Der tal

In tol—

A kval

Krishtol.

Un shtil

Zayn kol:

Taltil

Taltol.

In the desert, every discrete feature and creature of the natural world commands attention. “Tall pillars of light, like riders with shiny trumpets, issue an eleventh commandment. . . . V’ohavto l’artzkho kamokho.”God’s instruction in Leviticus 19:18 reads, “You shall not take vengeance or bear a grudge against someone from your nation. Love your fellow as yourself.” Adapting the Hebrew, Sutzkever substitutes, “Love thy country as thyself.”

For the first time in a decade, Sutzkever was once again out in the natural world that he adored, in a landscape strikingly different from the lush countryside around Vilna. Among the keepsakes that Sutzkever treasured was the slim publication of a botanist friend who had charted the flora in the Vilna region. He himself had always approached nature less as naturalist than fellow-creature. But though he craved that immediate contact more than ever, his observations were now clouded by what he had experienced during those intervening years. A small stone hangs precariously atop a huge boulder to be knocked off by any wind. Why? A flock of goats, black and white, flies into the valley like a run of piano keys, but, once there, their shadows are uniformly black. Why? The wild rose in the waterfall has a more enticing image underwater, but when he reaches for the refracted rose, it is no less thorny. Why?

In another poem, a stork reminds him of the one that perched on a birch tree across from their house one summer of his childhood and flew off at Sukkot-time, probably to Bethel. When the present one takes off, he imagines it flying back to his childhood home and finding the cloud of smoke. “I’m afraid its heart will burst. My friend the stork.”

Sutzkever arranged the poems of the desert in a thematic arc rather than following his actual itinerary: Beersheva, Ma’ale Akrabim, Wadi Jerafi, Ras el Naqb, then down to Eilat, Sinai, and Sodom. At the site of a key battle in the War of Independence, the poet hails “Samson’s Foxes,” the name given to the outstripped and underequipped unit that captured the outpost from the Egyptian army with tactics reminiscent of Samson’s victory over the Philistines. But the vertical connection that archeologists seek and that Israelis cherish is never as important to Sutzkever as the fact that these soldiers had gathered themselves “from the Vistula and Danube, from the Ganges and Dnieper” to be what providence needed them to be. Wherever he sees it, Sutzkever marks the forged unity of a reconstituted people.

There were Zionists who quipped that you could take the Jew out of exile, but you can’t take the exile out of the Jew. They feared that the Jews, like those in the story of the Exodus, would want to return to Egypt. Sutzkever’s fear was, instead, that, once they returned home, Jews would discard the precious fruits of the civilization they had continued to forge outside the Land of Israel. As the book advances, the poems register increasing anxiety over whether the Jewry of Babylon-Poland can be successfully reinterred in the Land of Israel. That image of reinterment also comes from Exodus (13:19–21), in which Joseph exacts an oath from the children of Israel to bring his bones from Egypt home for burial. Sutzkever deplores his generation’s failure to do what the Israelites did in their time: “The bones of Joseph here under sands, the bones of Joseph there, under Poland— / scarcely recognize one another and slash like knives and glow like coals.” These two communities lie not only separate but estranged. The coals with which “The Bones of Joseph” ends evoke the crematoria of Treblinka and the funeral pyres outside Vilna more than coals one might stoke back into a creative fire.

Indeed, the book heads backward, to remembrance of Vilna and its harrowing end. In exploring Israel, Sutzkever himself may have feared losing touch with his past. Or, more likely, his freedom to explore activated a corresponding drive to excavate the worst as well as some of the sweetness of his youth. Of his time in the ghetto, he recalls being tempted by hunger “like Lilith” into eating a swallow, and he remembers picking up a piece of coal in the cellar where he lay hiding to write a poem on the body of the dead man lying beside him. He describes the terrible damage such actions did to his soul, eager to reveal the depths into which he had been pressed as though saying to his readers, “I will bring the Polish past into the Israeli present for you to know who I am.”

In Moscow, after his rescue, Sutzkever had transcribed whatever he could recall about the German actions in the ghetto and who had committed them. Reading that account, Fun vilner geto (Of the Vilna Ghetto, 1946), an admirer of Sutzkever’s was disappointed by its seemingly careless mixture of ghetto history with personal details. But the book was not supposed to be a well-wrought urn. It wasn’t art; it was raw evidence for the prosecution against those who tried to destroy the evidence of their crimes. Writing with what little documentation he had at hand, Sutzkever described whatever he could personally confirm. (The book, edited by Justin Cammy, will soon appear in English.)

Once in Israel, Sutzkever faced a different literary task. If the Jewish exiles of Babylon had once asked how they could be expected to sing of Zion on foreign soil, the liberated Jewish poet had to celebrate the recovered homeland without for an instant forgetting the murdered third of the Jewish people that still lay unavenged “where skulls of days stiffen / In a bottomless, uncovered pit.” He took up the challenge as no other poet ever had. These poems formed themselves day by day; only when he collected them for publication in this book did he order them in this remarkable sequence—first, thanksgiving for the fulfillment of millennia of yearning; then fresh, eager exploration and rediscovery of the old-new landscape; and, finally, release of memory beyond even the reach of nightmares.

Fun vilner geto described Germans rounding him up with an elderly Jew and a terrified young boy and forcing them to dance around burning Torah scrolls for public amusement. The poem based on this sadistic sequence seems far removed from the book’s opening blessings of Zion—but not so far after all. Here—pared to its essence—there are only two captives: the old Jew “with the Torah in his hands, as though just down from Sinai,” intoning some of the verses that are going up in the pyre, and the poet, who asks his elder whether this is the reward for his yet-unlived life. The old Jew discounts the question: “Being a Jew means being prepared for every trial, oyf nisoyen un oyf nes, for trial and miracle.”

The elder’s wordplay, worthy of a poet, incorporates the expectation of miracle in the martyrdom so that he is not accepting death for God’s sake but with an expectation of life against all odds. Grateful for this instruction, the poet sees his companion swept up in the eponymous chariot of fire and lifts his cloak as Elisha once did Elijah’s. In his reflections on “tradition and the individual talent,” T. S. Eliot showed how new poets transform our reading of old classics, and, just so, when Sutzkever’s readers turn to the second book of Kings, they will now see, as I do, the poet attending this bearded Vilna Jew as he ascends with Elijah.

Other poems in this late part of the book recall further images of the ghetto’s destruction, the murder of its children, and the bravery of individual Jews. Whereas the purpose of his account in Fun vilner geto was to prosecute the Nazis, these poems obliterate their presence to concentrate on the Jewish response. In the highly inflected way that Yiddish uses language for moral clarity, Jews insert the phrase yimakh shemam—may their names be erased—after every mention of the murderers. So, too, Sutzkever’s poems.

But this is not yet how In fayervogn ends. Readers of Sutzkever’s early work cannot be surprised that his first postwar book of lyrics ends with “A Letter to the Grasses”—13 letter-poems on the eternal mysteries of divine and human creation. The Hebrew Bible, sourcebook of the Jewish people, begins with creation because, no matter how very consequential the Jews are in history, they testify to something beyond themselves.

In the first of these poems, the poet is not numb but not yet creatively alive. Severed from memory like the child from its womb, like the rose in a vase, he cuts himself with a piece of glass to persuade himself that the “goldsmith of pain” hasn’t lost his touch. And lo!—just as he had hoped—a rare joy invades his limbs. “Good evening to you, grasses, here we are again!” This cut into the flesh—neither a histrionic gesture nor the suicide he had once (reasonably) contemplated in the ghetto—revitalizes the birth of poetry within himself.

When he wrote this “letter to the grasses,” Sutzkever was heavily burdened with personal and collective responsibilities, all of them now available to his biographers through a vast correspondence. They will find his romantic liaisons with other women less interesting than the unbreakable union with his wife, the childhood sweetheart who saved his life in the forests in the winter of 1943 and knew him well enough to grant him that freedom. Even more distressing than the constant maneuvering to secure his journal and his family were the petty jealousies that pursued him. The one that prevented him from coming to New York for a decade, allowing us to host him first in Montreal, was a denunciation to the State Department that, while in Moscow, he had been an asset to Stalin. This especially distressed him because of the risks he had taken during his time in the Soviet Union on behalf of Stalin’s victims. “It’s a million-fold lie and frame-up that I ever belonged or was even close to the Communist Party in any way, shape or form. Not in Vilna, not in Russia, not in Israel. In fact, it was just the opposite. It’s a false denunciation by whom I do not know.” How awful if his life should someday be presented in such states of agitation. Though the politicking of Yiddish has never abated, Sutzkever was inherently apolitical, not the way some writers try to maintain strategic neutrality, but because his idea of poetry was not compatible with any lesser allegiance.

Sutzkever’s real biography is charted in his poems. This 13-part letter to the grasses—13 being the number of the Maimonidean principles of Jewish faith—reflects his own faith. “The hand of the poet fills me with wonder,” writes the poet of the power that comes from beyond himself to produce something apart from himself. The poem, likewise, reflects on its separation from the living voice of its creator and regrets having to turn from melodious to papery. Interwoven in these poems are images for the making of poetry that Sutzkever continually returned to from the start to the end of his writing life.

The supernatural compulsion that commands this art makes it hard to be Ibn Gabirol “but also makes it hard—not to be him.” Here again, Sutzkever’s model of the poet remains as it is throughout this book, the liturgical poet in the Iberian tradition who recognizes no barrier between secular and pious and feels no need to choose between loving a woman or God. He is like the Hebrew prophet who carries his words to term as a messenger of a higher power, but, whereas the prophet reports to the Lord of the Universe, this poet’s affinity is with the grasses. In parting, Sutzkever hopes that they will someday sprout at his headstone.

Sutzkever’s writing on poetry is delicate and modest. Still, this return to the Land of Israel leads one to think about how the history of the Jews, filled with so much dross and horror from the beginning, was transmuted into the Hebrew Bible. How did the story of Elijah emerge from Moab’s war against Israel? And how does Sutzkever’s book of thanksgiving and discovery, of remembrance and reinterring, lift off from the crematoria?

Poetry can sometimes release the miracle, the nes that is locked in the nisoyen, the trial.

Suggested Reading

The Poet from Vilna

Avrom Sutzkever and Max Weinreich, a memoir.

Funny How a Poem Can Get Under Your Skin

On Celia Dropkin’s avant-garde Yiddish break-up poem and a political insight.

Yiddish Genius in America

The great Yiddish poet Jacob Glatstein wrote two autobiographical novels and envisioned a third, set in America. Why didn’t he write it?

On a Story by Delmore Schwartz

In 1937, the editors at Partisan Review placed “In Dreams Begin Responsibilities,” by a 24-year old unknown improbably named Delmore Schwartz before pieces by Wallace Stevens, Lionel Trilling, Edmund Wilson, and Pablo Picasso, to relaunch their magazine. They knew what they were doing.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In