Repentance and Desire

Yom Kippur is a day that most contemporary Jews associate with somber reflection and sensory deprivation. Yet, according to the Rabbis of the Mishna, it is actually one of the two most joyous days in the Jewish calendar. The other, Tu b’Av, is a holiday of love. The centrality of joy, love, and human desire to Yom Kippur is explored by Israeli teacher and speaker Rabbanit Yemima Mizrachi in her recently translated book, Yearning to Return: Reflections on Yom Kippur.

In 2010, the newspaper Makor Rishon named Mizrachi, or Rabbanit Yemima as she is known throughout Israel, the third most influential religious woman in the country. In recent years, her audience has only grown, and right now, she may well be the foremost female Jewish educator in the world. Before COVID-19, thousands of female followers across the religious and cultural spectrum attended her effusive weekly sermons in person, and thousands more still watch them online through paid subscriptions. She publishes popular weekly newsletters in Hebrew and English and runs a center for at-risk youth with her kabbalist husband, Rabbi Chaim Mizrachi. In addition to her teaching, Mizrachi has become something of a spiritual guru, visiting hospital rooms and shiva homes across Israel, bestowing blessings on those who ask.

A typical Mizrachi lecture explores a biblical theme by relating it to her own spiritual growth and her listeners’ personal growth as women. Although her Hebrew prose is fairly concise, her speaking style is baroque. She layers Jewish sources upon Jewish sources (rabbinic, philosophical, Hasidic), punning as she goes. She tells anecdotes from her visits to victims of terror or tragedy, weaving their messages of resilience into her broader themes, many of which highlight the inherent strength or beauty of the Jewish woman. She has a sharp sense of humor, and ironically references herself and her fame: “I went with my family to the zoo. No one took pictures of the animals; they only took pictures of me.” Mizrachi’s lectures are creative and draw on a deep well of Jewish learning. But they do not attempt to persuade an audience with sophisticated intellectual arguments. They instead aim to inspire and strengthen pre-existing religious convictions through a dramatic, performative mode that is itself a kind of religious experience for Mizrachi and her audience.

In the recent months of lockdown, quarantines, and canceled school, Mizrachi has focused a great deal of her considerable energy helping her audience tackle the challenge of embracing and elevating the seeming burdens of domesticity, already a familiar theme in her work. As Mizrachi self-mockingly writes in Yearning to Return:

I prepare brilliant insights and sophisticated ideas, and then I realize that I am standing in front of a room of exhausted women who have come from near and far. I say to myself, “Enough, Yemima. Keep it simple. Touch people. Everyone has come to your lecture because they are in love, because this is what they fervently wish for, because they simply can’t let themselves miss out on this opportunity.”

The centerpiece of the book is Mizrachi’s interpretation of a medieval poem by Abraham ibn Ezra, which is read in Sephardi synagogues during Yom Kippur services:

My longing, My God, is for You

My desire and love is for You

My heart and innards are Yours

My soul and breath are Yours.

Mizrachi describes the scenes of spiritual longing and connection she sees all over Israel during the week leading up to Yom Kippur:

People gather; they make their way from lectures on spirituality to Selichot services, and the streets of the city resemble a great big pajama party. Everyone is out in the streets, men and women alike, and what are they all searching for? Faith.

Mizrachi identifies the heightened energy she senses in the streets of Israel during the days between Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur. She renames the period between Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur known as the Ten Days of Repentance, “Aseret Yemei Teshuva,” as the “Aseret Yemei Teshuka,” or “Ten Days of Desire,” a time when the yearning for a return to God and Torah reaches a primal, visceral level. Mizrachi’s distinguished translator Ilana Kurshan nobly attempts to reproduce the wordplay in English: “Ten Days of Repentance are not just about penance, but also about pining.” Whether this pining is for God or for a lover or spouse is largely irrelevant. She describes a scene which would likely irritate many speakers but for Rabbanit Yemima is a source of inspiration:

Sometimes, after I have taught an inspiring class, a woman in the audience will approach me with just a tiny question. She’ll say, “Rabbanit, please tell me. Will he come back to me or not?” How can I possibly know? Am I a clairvoyant? Can I see the future? I so desperately want to envision a happy ending for this woman whose suffering makes everything seem bleak. I am not a prophet, but I know that she has profited on account of her afflictions. They have made her great.

This idea of the “afflictions of love,” which God mysteriously visits upon the innocent is a trope that goes back to the Talmud, but here Mizrachi gives it a characteristic twist, making it part of what she calls Torah Nashit, a distinctly feminine (if not, perhaps, feminist) approach to Jewish texts.

Mizrachi’s equation of divine love and human love goes beyond metaphor to self-help. A large section of the book is titled “Human Relations as the Avoda Service,” that is as a version of the sacrificial service of the ancient Temple. In discussing the delicate, sometimes impossible, art of reconciliation between people, Mizrahi is her most clear and least romantic. One needs to sort out one’s own personal conflicts before they can get serious about repentance: “A misanthrope cannot love God. If we do not love other people, then our relationship with God is necessarily needy and selfish. Only when we love others can we genuinely love God, because in our love for others we become like God.”

Mizrachi seems to be fashioning a language to discuss Judaism in contemporary Israel, one which speaks to the diversity of its population and the variegated nature of its religious commitments and levels of education. In doing so, she is joined by other popular female personalities such as journalist Sivan Rahav-Meir and renowned speaker and twice-bereaved mother Miriam Peretz, each of whom speaks to and for an audience that cuts across the much-lamented religious-secular divide in Israel, rendering it almost irrelevant.

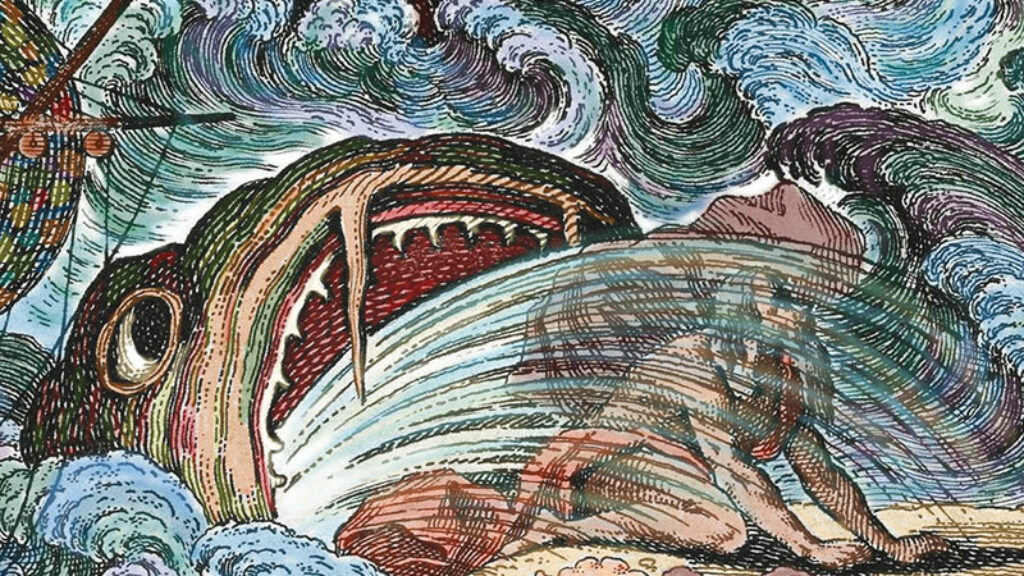

Several chapters of Yearning to Return analyze the prophet Jonah and his reluctance to speak to the people of Nineveh. For Mizrachi, Jonah is an elitist intellectual whose response to finding himself in the belly of a whale is to construct an exquisite prayer-poem. The people of Nineveh are deeply flawed, yet their simplicity and human vulnerability redeem them. Although Mizrachi herself has a more sophisticated intellectual background than might meet the eye (in addition to her Jewish learning, her father, a Rothschild scion, taught her Latin, French, and Arabic as a child, and she is a Hebrew University–trained attorney), she is on the side of the people. As she writes, “God tells Jonah that even beasts and even people who do not know their right hand from their left are great in His eyes,” which is one reason the story is read on Yom Kippur.

Mizrachi shares a parable from the Talmud of a king’s daughter who smells the fragrant spices stuck to the bottom of the pot and craves them (Pesachim 56a). She writes,

On Yom Kippur we are the burnt leftovers stuck to the bottom of the pot. We coronate God aloud. “Blessed be the name of His glorious kingdom for ever and ever!” We do not just speak these words. We yell. We roar. On this one day of the year, we are not embarrassed by how small we are relative to the greatness of the Divine. On this one day of the year, the king and queen need us. They need the masses to cry out, “Blessed be the name of His glorious kingdom for ever and ever!”

Yearning to Return is ultimately a tribute to ordinary Jews whose religious commitments may or may not be motivated by the loftiest religious principles, but who nevertheless seek God during the High Holidays. Mizrahi writes, “I believe with all my heart in the redemption of this nation, whose people are so good. I meet them in the streets, at conferences, and at lectures. I meet such wonderful women—religious, secular, Lithuanian, hasidic, Mizrachi, Ashkenazic, charedi. . . . I am in awe of how they care for and look out for one another.”

Is there a place in American Jewish life for someone like Rabbanit Yemima who can speak to and inspire everyone from the unaffiliated to the ultra-Orthodox? I’m not sure that there is, but English speakers desiring a glimpse of the collective Israeli, Jewish female conscience—or even just a motivational Yom Kippur read—can now encounter the phenomenon of Yemima Mizrachi for themselves.

Suggested Reading

Swimming in an Inky Sea

Ilana Kurshan, a hyper-literary, ideologically egalitarian, hopeless romantic (in her words), doesn’t fit the typical profile of a Daf Yomi participant.

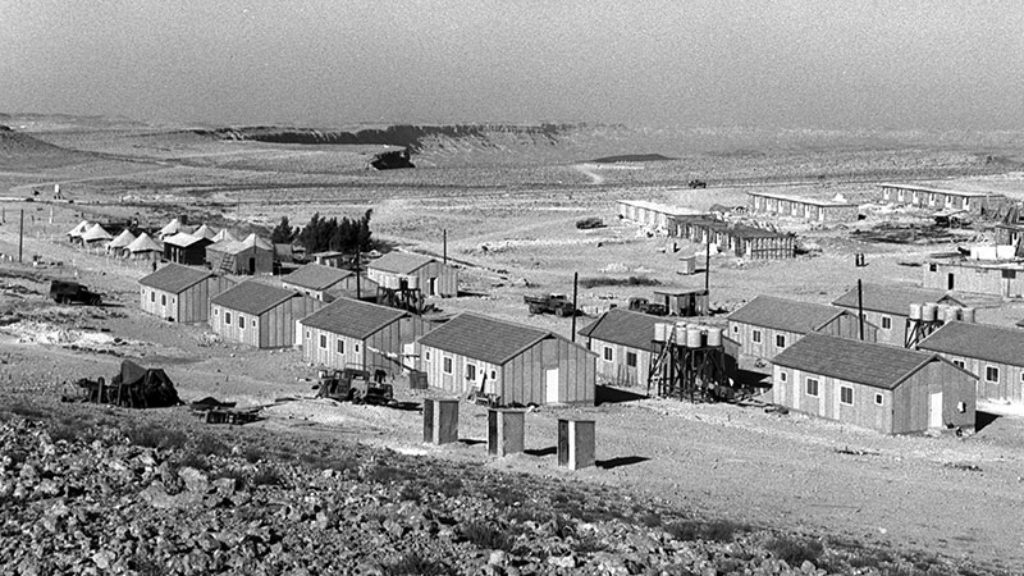

Seventy Years in the Desert

At the 1965 International Bible Contest, David Ben-Gurion posed some of the questions. He also asked two to the entire audience: “How many of you are ready to make aliyah to the Land of Israel?” And then, more specifically, “How many of you are ready to come and live with me in the Negev?”

Jonah: The Sequels

“And shall I not care about Nineveh, that great city, in which there are more than one hundred and twenty thousand persons who do not yet know their right hand from their left, and many beasts as well?”

At the Threshold of Forgiveness: A Study of Law and Narrative in the Talmud

In this season of repentance, it is not only the laws of the rabbis, but their stories as well, that teach us how—and how not—to forgive.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In