A Sharp Word

Vladimir Jabotinsky was born in Odessa in 1880 to a middle-class family and raised without much of a Jewish education. He seemed to be headed for a life in Russian literature, but then, in his early twenties, he suddenly and somewhat mysteriously became a Zionist. In his autobiography, he does say a few things to put this decision in context. Even as a child, he tells us, he was already looking forward to the restoration of a Jewish kingdom in Palestine. And as early as 1898, he recalls, he had made a “Zionist speech” at a student assemblage in Bern, Switzerland.

The historian Michael Stanislawski has cast some doubt on these memories. In his new book on Jabotinsky’s political activity from the ages of 20 to 45, Brian Horowitz, who also coedited the excellent recent edition of Jabotinsky’s Story of My Life, is less suspicious of Jabotinsky’s account, though he’s not entirely convinced either. Certainly, he says, Jabotinsky tells some dubious stories about his childhood that make “it seem like he embraced Zionism earlier than he actually did.”

The first verifiable trace of Zionism in Jabotinsky’s autobiography is an anti-anti-Zionist piece that he wrote in 1902, responding to a Jewish writer named Bickerman, who had ridiculed Zionism as utopian in a Russian-language journal. Horowitz, for his part, suggests that this may have been nothing but a “one-off.” But in 1903, Jabotinsky became “actively involved with Zionists.” By April, he was raising money for self-defense against a feared pogrom in Odessa and, according to another friend, intensively studying “Hebrew language, history, literature, the history of various national movements, and the colonial systems of different peoples—everything that, directly or indirectly, might pave the way to overcoming exile.” Nevertheless, according to Horowitz, it was really the Kishinev Pogrom, which broke out on April 19 and lasted three horrific days that was “the precipitating event” in Jabotinsky’s Zionist transformation. If he subsequently chose to obscure this fact, it was probably because he shied away from “acknowledging antisemitism as the stimulus for his Zionism.”

Horowitz, however, is much less interested in the question of how and when Jabotinsky became a Zionist than he is in figuring out his “development once he did embrace Zionism.” He reviews this development through what he calls Jabotinsky’s Russian years (1900–1925), even though he was outside of the country, mostly in Vienna and Constantinople, between 1907 and 1910 and left it in 1915 to lobby for what would eventually become the Jewish Legion, three Jewish battalions within the British Army. He never returned to Russia, and thus spent more than half of these years covered in Horowitz’s new book outside of the country. Nonetheless, he argues, Jabotinsky operated for many of those years within the context of the post-revolutionary “Russian-Jewish emigration.”

I had always thought of Jabotinsky as a somewhat starchy figure, in comparison, say, to Chaim Weizmann. His youthful amorous exploits were colorfully documented by Jehuda Reinharz in the first volume of his biography of Weizmann (and have a racy sequel in the third volume of that biography, which has just appeared in Hebrew). But Horowitz has dug up in the Jabotinsky archives a letter he wrote home from the 1903 Zionist Congress in Basel in which he described to a friend how he was almost given a summons after being “caught by a policeman in flagrante delicto with a Zionist lady on the cathedral grounds.” As Horowitz archly observes, “apparently Zionist congresses, like congresses everywhere, were characterized by extracurricular entertainments that often do not make it into the history books.”

One thing that has made it into the history books is Jabotinsky’s work as a Zionist theorist and activist in Russia in the decade after the 1903 congress. Those who have thought of Jabotinsky only as the man who criticized the mainstream Zionist movement in the 1920s and 30s for going too slow and aiming too low, who wanted both sides of the Jordan for the Jews, and who felt that Zionism should not be blended with socialism or anything else, should have learned by now, from Stanislawski, Hillel Halkin, Dmitry Shumsky, and others, that earlier in his career Jabotinsky was much more focused on the Jews’ preservation of their national rights in the diaspora. But, here too, Horowitz has mined new material.

There is, for example, Jabotinsky’s furious response to the prominent Russian liberal Pyotr Struve’s 1909 article, “Intelligentsia and the Face of the Nation,” which praised Jews who had integrated into Russian culture and who criticized those who did not. Jabotinsky, Horowitz tells us, did more than repudiate “Struve’s claims that the empire must have a Russian national character; he faulted the decent liberal Russians who ignored antisemitism,” and he did so in characteristically brutal bravura fashion:

During this time pamphlets and broadsheets that advocate tribal slaughter have flooded Russia, dozens of gutter newspapers are distributed on all corners that incite passionate hate toward Jews. Nearly the entire ideology of the reactionary movement leads to hate and would seem that the liberal Russian press should intercede on behalf of the persecuted if only because of a chivalrous need to defend the oppressed and fight this propaganda. The liberal Russian press did not do anything like this.

“Indeed,” Jabotinsky went on, “forgive me a sharp word: I found more nails driven into the dead pupils of [the eye] of one of the victims of the Bialystok Pogrom than articles about this pogrom in the liberal Russian press.” Horowitz notes that this rebuke isn’t really fair, but he also sees how Jabotinsky was trying to radicalize his Jewish readers to make them understand the extremity of their situation, as he saw it.

Jabotinsky wasn’t always as single-mindedly concerned with Palestine as he later became, but he was never a pussycat. Horowitz’s portrait of him engaged in rough-and-tumble polemics on a long-gone intellectual battlefield is both entertaining and instructive. It makes me wish that I could read his words in the original Russian. One hopes that Brian Horowitz will translate more of them—and follow up with another book on the last 15 years of his extraordinary life.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

A Normal Israel?

Zionism has long based its claim to sovereignty on the universal right to national self-determination, and the phrase “like all other nations” has been incorporated into Israel’s Declaration of Independence, yet the goal of “normalization” has proven to be much more complicated than most early Zionists had thought.

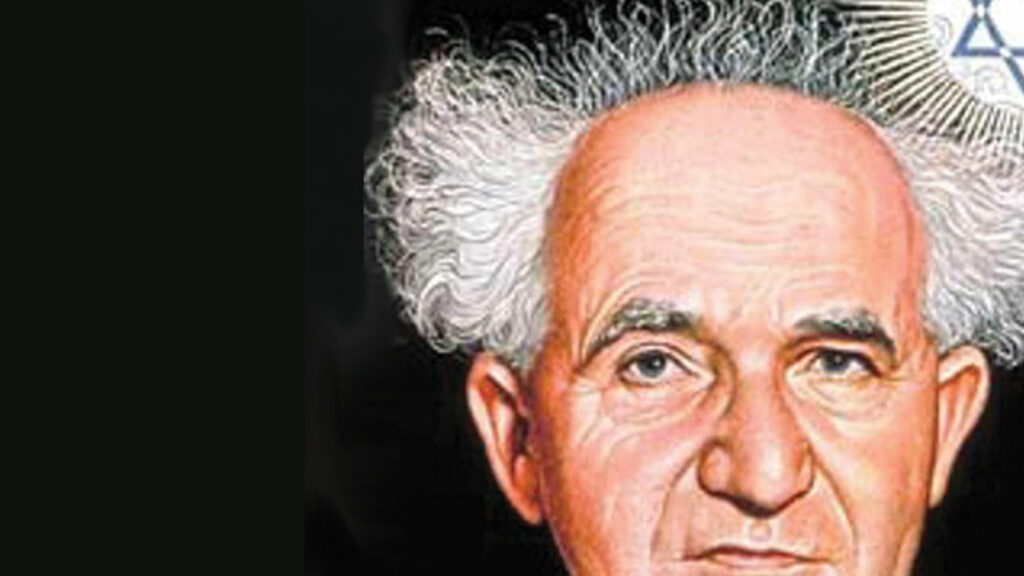

Indispensable Man

In his effort to cut David Ben-Gurion down to size, Tom Segev blames him for failures that were not his and gives him insufficient credit for his achievements. A closer examination of the historical record reveals a greater man than the one Segev attempts to dissect.

State or Substate?

“Nonstatist” Zionists, as the historian David Myers has dubbed them, have received a lot of attention in recent years. Dmitry Shumsky, a historian at the Hebrew University, is grateful for this scholarship but believes that it has not gone far enough.

Your Time Is Up: Jabotinsky at the Sixth Zionist Congress

The young Jabotinsky didn’t exactly take the Sixth Zionist Congress by storm. When he approached Chaim Weizmann, saying, “I hope I am not intruding,” Weizmann replied, “You are.” A newly discovered text, edited by Brian Horowitz and Leonid Katsis.

Solon Beinfeld

Jabotinsky translated Bialik's famous poem, "In the City of Slaughter", about the Kishinev pogrom, into Russian. Legend has it that the young Vladimir Mayakovsky, one of the great Russian poets, learned Jabotinsky's translation by heart.

Marcus moseley

Jabotinsky's autobiography is very strange.

It is almost as if he wishes to be caught out in his lies!

In which case they are not lies...

Kind of like Bob Dylan, with the wild fantasies of his Huck Finn childhood--yet pointing each and all to his background in Duluth and Hibbing.

Hic Rhodes hic Salta

Best,

MM