Ten Plagues, Three Acronyms, Seven Opinions

It rolls off the tongue about as easily as asking someone to “pass the salt” with your mouth full of matza.

The unwieldy acronym, D’tzakh Adash B’achav, has puzzled Haggadah readers both casual and scholarly ever since Rabbi Judah made what seems like the world’s least helpful mnemonic suggestion. Appearing in the Maggid section on the heels of the blood, frogs, lice, and the rest of the plagues, the value-add of breaking the ten plagues into three acronyms is not, as a corporate consultant might delicately put it, entirely apparent.

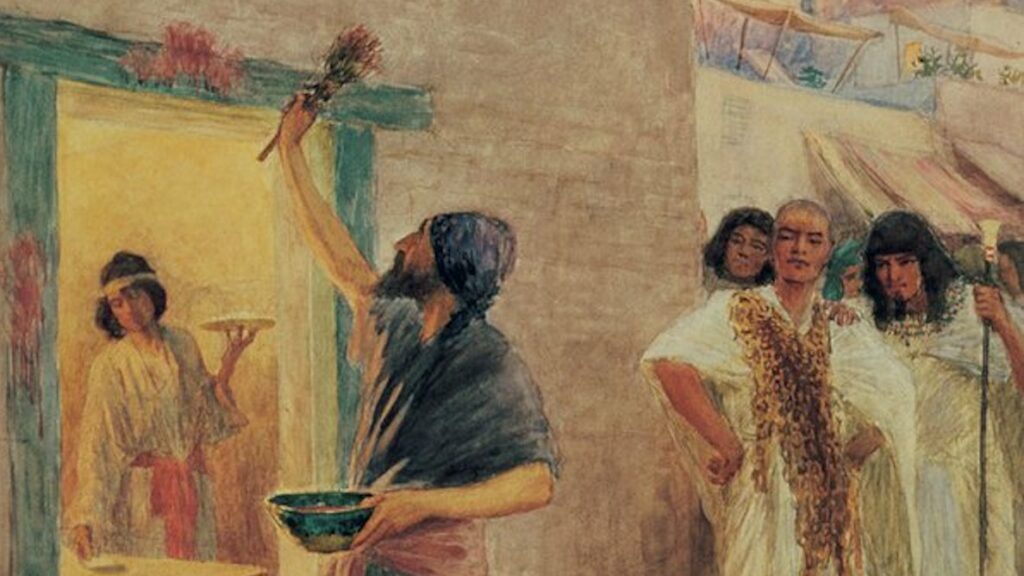

Rashi thought that Rabbi Judah’s mnemonic was a way of asserting that there were, in fact, exactly ten plagues and they happened in precisely the sequence described in Exodus, not in the manner of the shorter, differently-ordered descriptions in Psalms 78 and 105 that list frogs as third and darkness before blood, respectively. The Psalms are poetry, the text of Exodus is history. Rashi’s grandson, known as the Rashbam, understood Rabbi Judah’s point to be more conceptual than textual-historical. The first cluster of plagues summed up by D’tzakh —blood, frogs, and lice—demonstrated God’s rule over the ground. Adash—wild animals, pestilence, and boils—reflected God’s command of nature, and finally B’achav—hail, locust, darkness, and death of the firstborn (struck down by an unseen heavenly force)—showed God’s mastery over the sky.

The tosafist Rabbi Isaac ben Asher Ha-Levi suggested that Rabbi Judah’s abbreviation was actually an implicit argument that the ten plagues themselves were merely shorthand for a longer, more comprehensive attack by God against Egypt. As the Haggadah itself suggests, there were tens or even hundreds of other strikes against Israel’s oppressors that the Torah skimps on, or sums up, in its enumeration of ten plagues.

A little later, in the twelfth century, the great German pietist known as the Rokeach calculated that if one adds up all of the different opinions about the total number of plagues that, according to rabbinic suggestions in the Haggadah, were performed at the sea—50, 200, or 250—the gematria equals D’tzakh Adash B’achav. The acronym’s calculation is 501 and is actually off by one, but, as we know, that’s allowed in gematria. And as in the great after-party seder song “Who Knows One,” the One is, of course, God Himself.

The question of the significance of Rabbi Judah’s acronymic mouthful did not end with the middle ages.

The nineteenth century German theologian Rabbi Samson Raphael Hirsch, who was fond of symbolic explanations, suggested that the plagues in the acronym corresponded to measure-for-measure punishment for the three basic categories of suffering that the Egyptians inflicted upon the Jewish people. The first plague in each group—blood, wild animals, and hail—impressed on the Egyptians that they were not in control of their own natural resources. The second in each list—frogs, pestilence, and locusts—destroyed their pride by decimating Egypt’s economy. The third set—lice, boils, darkness (as well as the death of the firstborn)—physically tormented the Egyptians just as the they had tormented the Children of Israel during the centuries of enslavement and slaughter.

Hirsch’s Hungarian colleague Markus Horovitz offered a moderate reading of a rather harsh midrash which states that the names of the plagues were physically inscribed on the defeated Egyptians. Not the whole list, suggested Horovitz. Just the abbreviations, those “signs” of Rabbi Judah.

Recent decades have seen a further softening of what D’tzakh Adash B’achav might signal. In his recent work Moadim Uzmanim, the British-born Israeli rabbi Moshe Sternbuch suggests that Rabbi Judah’s acronym was intended to help more with our empathy than our memory. We shouldn’t rejoice in the downfall of our enemies, he argues, so no need to go into detail about each of the plagues by calling each by name. The specific details are not as important as the fact that they led to our redemption.

But, then again, perhaps Rabbi Judah had a much simpler intent in mind with his odd acronym: maybe he made it so that the children will ask.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

“Whoever Is Hungry, Come and Eat”? From the Babylonian Poor to the Ashkenazi Elijah

Why do we begin the seder by inviting “whoever is hungry” to come and eat? Aren’t the guests already at the table? And why do we do it in Aramaic? It has something to do with Babylonian magic bowls . . .

The First Maggid—How Memory Made the Jews

3,500 years ago, Israelite parents explained wonders to their children and created the very first Maggid story.

The Fifth Question

Whatever kind of Passover Seder one attends, there is a fifth question, usually whispered, that arises some time after the first four are asked . . .

The Secret Metaphysician

While a new crop of biographies about Gershom Scholem all, in one way or another, seek to account for the great man's fascination, they are themselves evidence of Scholem’s ongoing allure.

David Farkas

Enjoyable article, but I think Dr. Halpern left out the simplest, and hence most satisfying explanation of all: Rabbi Judah was simply prone generally to acronyms. The great Galician scholar, R. Reuven Marglios, pointed out several other places where this same Rabbi Judah employed acronyms or other forms of written shorthand, including JT Megilah 1:5, Yoma 55b, and more. As he notes, the Talmud itself refers to Rabbi Judah with the nickname "Simnai" ["the maker of mnemonics"], evidence of his predilection. This understanding, R. Margolios also observes, leads to a different, and less harsh understanding of the Midrash quoted by Dr. Halpern from Markus Horovitz. Thus, the acronym sub judice has no specific meaning for the plagues per se, but is merely part of a general habit of Rabbi Judah to minimize use of the written word.