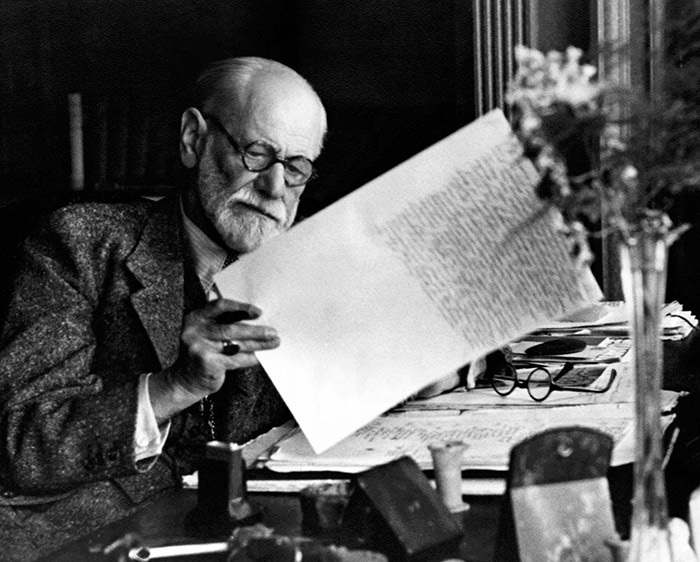

Freud as Talmudist

Sigmund Freud was bemused by Jewish attempts to take pride in his achievements. “The Jews have celebrated me as a national hero,” he wrote after his seventieth birthday in 1926, “although my merit in the Jewish cause is confined to the single point that I have never denied my Judaism.” For Freud, it was important not to be thought of as a Jewish thinker, even though—or precisely because—his first followers and most of his early patients were Jewish. He was certain that psychoanalysis was a universal, objective science, and as he wrote, “There should be no distinct Jewish or Aryan science. Their results should be identical.”

On this view, the fact that a Jew discovered psychoanalysis didn’t mean it was a “Jewish science,” any more than Einstein’s e = mc2 was a Jewish equation. For Freud, the adherence of Carl Jung, the most prominent Gentile among early psychoanalysts, was especially important as proof of this point. The most Freud was willing to grant was that being Jewish facilitated his discoveries by setting him outside the scientific and medical establishment of his time. “Because I was a Jew,” he wrote, “I found myself free from many prejudices which limited others in the employment of their intellects, and as a Jew I was prepared to go into opposition.”

The reality, of course, was always more complicated. In developing the principles of psychoanalysis, Freud used himself as a case study, which often meant writing frankly about his complicated feelings about being Jewish. That ambivalence was clearly legible in his last book, Moses and Monotheism, finished just before his death in 1939, in which he argued that Judaism began as an offshoot of Egyptian monotheism—a frontal attack on Jewish self-understanding, issued at the darkest moment in modern Jewish history.

In the late twentieth century, advances in psychology and neurology stripped away the scientific authority of psychoanalysis. This represented the defeat of Freud’s most cherished ambitions, but it also made possible a new way of thinking about him as a humanist—a philosopher, ethicist, and social critic. As a result, the Jewishness of Freud’s thought and identity came to center stage in studies such as Yosef Hayim Yerushalmi’s Freud’s Moses: Judaism Terminable and Interminable (1991) and Sander Gilman’s Freud, Race and Gender (1993). Still, these historians—like Peter Gay in Freud: A Life for Our Time (1988)—were primarily interested in how Freud, like other German Jews of his time, dissociated himself from Judaism. Yerushalmi writes of Freud as an example of the “Psychological Jew,” a modern type for whom Jewishness is “devoid of all but the most vestigial content; it has become almost pure subjectivity.” Similarly, Gay writes that Freud’s Jewishness was “elusive, indefinable,” coming to the fore primarily in encounters with antisemitism.

By his own account, Freud had little knowledge of Jewish texts and ideas. In every European Jewish community, the encounter with modernity led to a breakdown in the transmission of traditional knowledge, though this took place at different times in different places. In Freud’s family, it happened in the generation of his father, Jacob, who was born in a small town in Galicia in 1815 and moved his family to Vienna in 1860, when Sigmund was four years old. Jacob’s father, Schlomo, was a rabbi, and Jacob himself was educated in a yeshiva; Sigmund recalled that his father spoke Hebrew as well as he spoke German. Sigmund’s daughter Anna Freud remembered her aged grandfather studying Talmud at home.

But Freud testified that “my father allowed me to grow up in complete ignorance of everything that concerned Judaism.” Some scholars have made much of the fact that Jacob once gave his son a Bible with a Hebrew inscription, but when the adult Freud was given a book with a Hebrew message, he replied that he was entirely unable to read it. The belief that one’s children would be more burdened than fortified by Jewish knowledge was shared by many Jewish parents in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, in Brooklyn and Tel Aviv no less than in Vienna.

As for religious faith, Freud of course had none, identifying on occasion with Jewish unbelievers like Heinrich Heine and Baruch Spinoza. A strict rationalist, he theorized in The Future of an Illusion (1927) that the origins of religion lay in “the terrifying impression of helplessness in childhood,” which “aroused the need for protection—for protection through love—which was provided by the father.” God is the imaginary father adults call on to avoid confronting “the full extent of their helplessness and their insignificance in the machinery of the universe.” But “men cannot remain children forever,” Freud says, demanding that we emancipate ourselves from faith.

This biographical and intellectual distance from Judaism makes it all the more remarkable that Freud’s psychoanalytic methods often bear a close family resemblance to rabbinic ways of thinking. Susan A. Handelman observed as much in her 1982 book The Slayers of Moses: The Emergence of Rabbinic Interpretation in Modern Literary Theory, where she writes that psychoanalysis should be seen as a “continuation of the Jewish exegetic tradition.” Freud’s belief in the perpetual interpretability of the human mind, Handelman argues, is continuous with the rabbinic idea that “each word and letter of the Torah” contains “endless multiple meanings.” This Jewish understanding set Freud against the “literalism” of Protestant hermeneutics, which aimed at the discovery of a final, “univocal meaning in the Biblical text and in spiritual life.”

While intuitively convincing, this way of thinking about Freud runs up against the same biographical obstacle as David Bakan’s theory, outlined in his 1958 book Sigmund Freud and the Jewish Mystical Tradition, that Freud was influenced by kabbalism. Since Freud never studied the Talmud or the Zohar, how can these Jewish texts have influenced him? Bakan argued that Freud “consciously or unconsciously” engaged in Straussian dissimulation to conceal the fact that his psychoanalytic insights were “Kabbalistic in their source and content.” At the same time, Bakan hedges his bets by noting that “this does not mean that Freud had necessarily read [kabbalistic] literature.” Similarly, Handelman rightly points out that “many of Freud’s methods” of dream-analysis “bear striking similarity to some of the Rabbinic hermeneutic rules,” but to explain the mechanism behind this “return of Freud’s own Rabbinic repressed,” she must posit that Freud “pretended to forget” the Jewish knowledge he once acquired.

Turning the accusation of repression against Freud, who wielded it so freely against his patients and critics, may be a kind of poetic justice. But it doesn’t make up for the absence of any actual evidence that Freud knew enough about the Talmud, much less the Zohar, to have drawn on them in his own work.

Even if the resemblance between Freudian and rabbinic interpretation isn’t a case of direct influence, however, that doesn’t mean it’s a mere coincidence. Rather, it can be seen as a case of what biologists call convergent evolution, when unrelated species develop similar features to solve a similar problem. The fact that birds and butterflies both have wings doesn’t mean that one evolved from the other, only that both species found it beneficial to be able to fly. Likewise, perhaps Freud and the Rabbis developed similar hermeneutic tools because they were dealing with the same challenge: how to create useful meaning in a recalcitrant text, while continuing to believe they only found it there.

To understand the centrality of interpretation in Freud’s thought, the best place to begin is a book that places the term front and center: The Interpretation of Dreams, published in 1899. This seminal work introduced several of the key concepts Freud would elaborate on in the following decades, including the unconscious and the Oedipus complex. Most important, the principle Freud used to interpret his own and his patients’ dreams was the same one he later applied to mental life as such.

In The Interpretation of Dreams, Freud distinguishes between the “manifest content” of a dream—the things we experience while sleeping and remember after waking up—and the “latent content,” the hidden meaning that can be extracted with the help of psychoanalysis. “Our doctrine is not based upon the estimates of the obvious dream-content, but relates to the thought-content, which, in the course of interpretation, is found to lie behind the dream,” Freud writes. In later works he used the same distinction to analyze the words we utter by mistake—“Freudian slips”—and the irrational phobias of the patients who sought his help.

Freud was trained as a medical doctor, and using the visible to understand the invisible is medicine’s stock-in-trade. The word “diagnosis” comes from Greek roots that mean “knowing through,” and medical diagnosis involves seeing through a symptom to the condition that causes it. Symptoms are sometimes loosely referred to as signs—you could say that sweet-smelling urine is a sign of diabetes—but they are essentially different from linguistic signs. A symptom is a direct result of whatever is going wrong on the level of cells and molecules: a patient’s urine is sweet because it contains sugars that the body is unable to metabolize. The name of the disease, by contrast, is a completely arbitrary sign. It makes no difference whether you call it diabetes in English or Zuckerkrankheit in German, since words have no inherent connection with the things they refer to.

It follows that interpretation is a different process when applied to symptoms and to signs. To interpret a symptom is to understand what is happening inside the body to cause it. To interpret a sign is to understand what it was intended to convey by the person who used it. A sign implies the existence of a mind with a purpose; a phenomenon is only a sign if there is someone “behind” it.

The power of The Interpretation of Dreams comes from the way Freud fuses—really, confuses—these two kinds of interpretation. On the one hand, dreams are symptoms that help the physician understand the patient’s underlying psychic disorder: “The next step was to treat the dream itself as a symptom, and to apply to it the method of interpretation which had been worked out for such symptoms,” he writes.

Yet Freud thinks about dreams as purely psychic phenomena, not physical symptoms of the kind a doctor usually deals with. As a materialist and rationalist, he would presumably grant that what he refers to as psychic processes correspond to changes in the brain, but in The Interpretation of Dreams he is completely indifferent to neurology. “We shall wholly ignore the fact that the psychic apparatus concerned is known to us also as an anatomical preparation, and we shall carefully avoid the temptation to determine the psychic locality in any anatomical sense,” he declares.

By dispensing with anatomy, Freud makes it impossible to investigate dreams as symptoms. Because they are strictly psychic phenomena, they can only be interpreted as signs—that is, as communications. This was also the prescientific view, as Freud acknowledges: “The belief of the ancients that dreams were sent by the gods in order to guide the actions of man was a complete theory of the dream.” His own simple but revolutionary innovation was to say that dreams really are communications, but not from the outside. Rather, they are communications from one part of the mind to another—from the unconscious to the conscious.

It follows that dreams must be interpreted in the same way as other types of signs, by trying to understand what their creator “means” by them. The double nature of dreams, the fact that they are both signs and symptoms, is why psychoanalysis can offer an unprecedented kind of therapy, the “talking cure.” For Freud, interpreting the dream-as-sign and relieving the dream-as-symptom are one and the same activity. This is also true of neuroses, which have the same double nature as dreams. Indeed, Freud says that “the lines of approach to the comprehension of the dream were laid down for me by previous investigations into the psychology of the neuroses.”

In The Interpretation of Dreams, then, Freud understands dreams as linguistic artifacts that need to be “read,” often in just the same way that we read a text. “The dream, indeed, is so intimately connected with verbal expression that Ferenczi justly remarks that every tongue has its own dream-language,” he writes. Later he adds, “The part played by words in dream-formation ought not to surprise us. A word, as the point of junction of a number of ideas, possesses, as it were, a predestined ambiguity,” making it ideally suited to the obscure communications dreams like to deliver.

Much of the work of dream-analysis, then, turns out to be verbal analysis. In one case reported by Freud, a young man dreams that the weather has turned cold and he must put on a heavy overcoat, which makes him unhappy. For Freud, the key to this seemingly prosaic dream is that the German word for overcoat—Überzieher, literally “pullover”—is also slang for a condom: having to wear a condom would make the man unhappy by making sex less pleasurable. In another case, an elderly woman dreams that after collapsing in the street she is sent home in a cab, into which an unknown hand throws a heavily laden basket. Freud, observing that the word Korb can mean both “basket” and “rebuff,” interprets the dream as a regretful memory of the potential lovers she rebuffed when she was young.

When Freud analyzes his own dreams, the chain of verbal associations can become amazingly complicated. In one example, he dreams that he is hungry and goes into a kitchen to ask for food, but the three women working there tell him he has to wait. Then he leaves the kitchen and puts on a coat, but it is too long for him. Analyzing the dream, Freud starts by remembering a novel he read when he was thirteen years old, in which the hero goes insane and calls out the names of three women he has loved; one of the names is “Pelagie.”

Next Freud recalls that one of the dream-women in the kitchen was rolling something in her hands, as if shaping a dumpling. The German word for “dumpling” is Knödl, and Freud remembers that when he was a university student, he heard about a man named Knödl who was sued for plagiarism. The name Pelagie echoes the word “plagiarism,” which in turn evokes the Latin term Plagiostomi, an order of fish, which Freud says is connected with another college memory (though he doesn’t explain what it is). In the nineteenth century, fish bladders were used as condoms, so Plagiostomi leads in turn to the image of putting on an Überzieher, a condom/coat. Through this chain of verbal associations, Freud concludes that his dream about hunger is really about a different impulse, sexual desire, which is tabooed and so “must conceal itself behind a dream.”

Not every dream-analysis in The Interpretation of Dreams relies so heavily on wordplay. Freud sets out a number of other methods and rules for eliciting “latent” content. For instance, objects that can be thought of as resembling genitalia must be understood as sexual symbols: “all sharp and elongated weapons, knives, daggers, and pikes, represent the male member.” So do neckties, women’s hats, “complicated machines and appliances,” “all weapons and tools,” and even children: “The little brother was correctly recognized by Stekel as the penis.”

Along with a vocabulary, dreams also have a grammar. “One learns in a psychoanalysis,” Freud writes, “to interpret temporal proximity by material connection; two ideas which are apparently without connection, but which occur in immediate succession, belong to a unity which has to be deciphered.” When two objects appear close together in a dream, “it vouches for a particularly intimate connection” between the thoughts they stand for, just as two letters written with no space between them “are to be pronounced as one syllable.”

Then again, dreams often represent things by their opposites, so that Freud says it is “always permissible, if a dream stubbornly refuses to surrender its meaning, to venture on the experimental inversion of definite portions of its manifest content. Then, not infrequently, everything becomes clear.” When the unconscious has so many tricks up its sleeve, it’s no wonder that analyzing a dream is extraordinarily complicated: “The dream, when written down, fills half a page; the analysis, which contains the dream-thoughts, requires six, eight, twelve times as much space.”

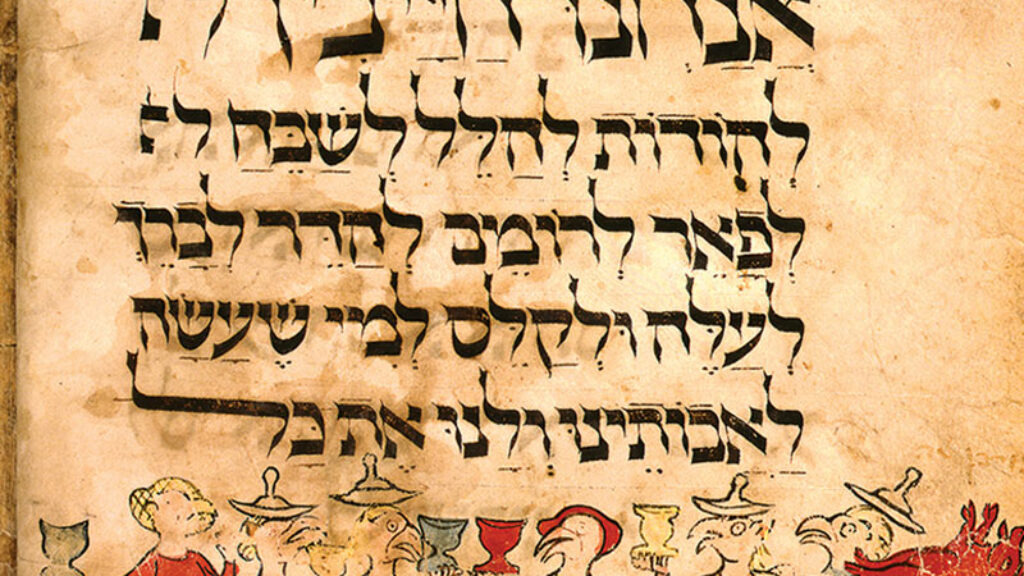

If Jacob Freud had been alive when The Interpretation of Dreams was published, he might have pointed out to his son that the same ratio of interpretation can be found in the Talmud, where a few lines of Mishna often give rise to many pages of Gemara. Just as the meaning of a dream is far richer than can be guessed from the events alone, so the meanings of Torah, both Oral and Written, go far beyond what the text says explicitly. Freud’s distinction between the manifest content of a dream and its latent content parallels the rabbinic distinction between peshat, the plain meaning of the Torah’s words, and derash, the meaning revealed by interpretation.

In dream analysis as in midrash, this disparity arises because the material to be interpreted is supersaturated with meaning. Ordinarily words mean what they say, but the unconscious, like God, operates beyond the ordinary limits of human intelligence, packing meaning into every line, every letter. Freud could say about the dream what Ben Bag-Bag says about Torah in Pirkei Avot: “Turn it and turn it, for everything is in it.”

Precisely because this “everything” is not apparent, eliciting it from the material requires going beyond commonsense methods of interpretation. This makes expert analysis often seem arbitrary to an outside observer, who doesn’t know the esoteric but strict laws of hermeneutics. Freud’s rules of interpretation, as we have seen, treat the simultaneity of events, the resemblance of objects, and the similarity of words in a dream as signifying particular kinds of connection. He also finds meaning in proximity, inversion, and negation. This battery of interpretive rules gives the analyst the power to coax a coherent meaning out of the seeming chaos of the dream. In a dream, Freud writes, “everything is definitely determined, and nothing is left to caprice.”

The Rabbis have their own battery of rules for the same purpose. Hillel is credited with the seven middot used in the Talmud to interpret biblical verses, often for the purpose of grounding provisions of the Oral Torah in the words of the Written Torah. For instance, kal v’chomer, literally “light and heavy,” is the same principle known in Latin as a fortiori, reasoning from a weaker case to a stronger one. A familiar example can be found in the Haggadah: If we would thank God for performing any one of the Exodus miracles listed in the Dayenu, “how much more so should we be grateful to the Omnipresent” for performing all of them.

The middah that most closely resembles Freud’s techniques is gezeira shava, the use of verbal analogy. This rule allows the Rabbis to connect any two verses in the Bible, no matter how unrelated they seem, if they contain the same word, making possible some extraordinary feats of deduction. A good example can be found in Eruvin, 51a, where the Gemara asks how we know that it is forbidden to walk more than two thousand cubits on Shabbat. This figure is not stated anywhere in the Torah; all it says in Exodus 16:29 is “Let no man go out of his place” on Shabbat.

However, the word “place” also appears in Exodus 21:13, a verse dealing with places of sanctuary for accidental manslaughter: “I will assign you a place to which he shall flee.” The word “flee” in this verse also appears in Numbers 35:26, alongside the word “limits”: “But if the killer ever goes outside the limits of the city of refuge to which he has fled. . .” Then the following verse uses the word “limits” and the word “outside”: “And the blood-avenger comes upon him outside the limits of the city of refuge. . .” Finally, in Numbers 35:5, the word “outside” appears alongside the measurement in question: “You shall measure off two thousand cubits outside the town on the east side.”

There is a striking similarity between this relay race of interpretation and Freud’s analysis of his dream, which establishes its own verbal chain: three women–novel–Pelagie–plagiarism–Plagiostomi–fish bladders–condoms–sexual frustration. Of course, neither in the dream nor in the Bible could a lay reader expect to discover the exact sequence of associations on his own. This makes interpretation a fundamentally different process from scientific experiment, whose results can in principle be replicated by any investigator. Galileo may have been the first person to formulate the rule that all bodies fall at the same rate regardless of their mass, but anyone with a roof and some things to throw off it can prove it for themselves. By contrast, no one simply hearing an account of Freud’s dream could have hit on his interpretation of it, just as no reader of the Torah unequipped with gezeira shava could deduce the two-thousand-cubit rule.

To the critical reader, this unverifiability is proof that both psychoanalytic interpretation and rabbinic hermeneutics are based on a misunderstanding. Both believe that they have found in the “text” a meaning they have actually put there. In Freud’s own view, by contrast, the discrepancy between the manifest content and the latent content of a dream is what reveals the existence of a “censor,” a psychic agent that prevents our unconscious desires from coming to consciousness. Freud would later name this censor the superego, and the premise of psychoanalysis is that neurosis can be overcome by confronting desires and memories that the superego has repressed. Notably, the metaphor of censorship is once again verbal, textual: the psychoanalyst helps us read the crucial passages that the censor’s pen has inked over.

Because dreams are overcharged with meaning, it is impossible to overinterpret them. Indeed, Freud writes that dreams “are capable of hyper-interpretation, and even require such hyper-interpretation before they become perfectly intelligible.” From a psychoanalytic perspective, to say that the analyst has given the dream a meaning foreign to it is to underestimate the cunning of the unconscious, the many strange ways it has of slipping messages past the censor. When a patient rejected Freud’s interpretation of a dream, he took it as further proof that his interpretation was correct, so much so that it had activated the patient’s resistance to the analyst’s unwelcome insights. For the philosopher Karl Popper, this refusal of “falsifiability” was what disqualified psychoanalysis from the status of a science, which Freud so coveted for it. “As for Freud’s epic of the Ego, the Super-ego, and the Id, no substantially stronger claim to scientific status can be made for it than for Homer’s collected stories from Olympus,” Popper wrote in Conjectures and Refutations: The Growth of Scientific Knowledge (1963).

Similarly, the premise of midrash is that the Torah requires hyper-interpretation because God is unbound by human rules of grammar and logic. If God wants to communicate a halakhic principle by means of a single letter or prefix, or if he wants to conceal the meaning of one Torah verse inside a distant, totally unrelated verse, who are we to say that he can’t or wouldn’t? To a believer, the improbability of a talmudic interpretation isn’t an argument against it; rather, it is a tribute to the infinite significance of Torah, which reflects the infinite mind of its author.

For this reason, both psychoanalysis and rabbinic tradition make themselves immune to disproof by rational argument, because each grounds itself on an axiom that lies in the realm of faith. If the Torah is a message from God, then it can and must be infinitely interpretable; if a dream is a message from the unconscious, it must be very nearly as interpretable. Ironically, this very plenitude of possible interpretations means that the authority to interpret must be carefully guarded. It belongs to the founding teacher and is passed down apostolically to a trained elite, who can be trusted to make the correct deductions. Challengers to this authority are heretics and must be expelled; that is what happened to the Sadducees, the Karaites and the followers of Shabbtai Zevi, as to Freud’s disciples Sándor Ferenczi and Jung. Here again, the history of psychoanalysis reveals that it is not to be classified as a science but as a spiritual movement.

To reject either system of interpretation it is necessary to strike at the root: to deny the divinity of the Torah or to deny the existence of the psychic agencies posited by psychoanalysis. This requires what the philosopher of science Thomas Kuhn called a paradigm shift, in which our ways of thinking change even as the phenomena we’re thinking about remain the same. Maimonides and Spinoza, for example, were both aware that the Torah made statements a philosopher could not accept. For Maimonides, the solution to this problem was to radically reinterpret the language of Torah to bring it into conformity with reason, on the assumption—which is ostensible, at least, in the Guide of the Perplexed—that the Torah must be a source of truth.

For Spinoza five hundred years later, it was possible to offer a more straightforward solution: the Torah is indeed capable of error, because it is the work of human beings and not God. According to this rational, critical view, the people who wrote the Torah didn’t choose every letter with a particular meaning in mind; they just wrote, the same way a secular poet writes an epic. Later interpreters thought they were finding meanings in each letter, but actually they were inventing these meanings. Just so, for Freud, the amazing thing about dream-analysis was what it revealed about the resourcefulness of the unconscious. Today, what seems amazing in The Interpretation of Dreams is the resourcefulness of Freud himself, the way he can connect every element in a dream to every other, and all of them to his own theories.

Oddly enough, the Talmud itself makes this very critique of dream-analysis. In tractate Berakhot, there is a long discussion of dream interpretation, in which Rav Hisda agrees with Freud that dreams are communications: “a dream not interpreted is like a letter not read.” The Gemara goes on to offer a dictionary of images akin to Freud’s catalog of phallic symbols: a river or a well seen in a dream signifies peace, an ox is a sign of imminent death, and so on.

At the same time, however, the Rabbis recognize that dream interpretations are essentially arbitrary. “Rabbi Bena’a said: There were twenty-four interpreters of dreams in Jerusalem. One time, I dreamed a dream and went to each of them. What one interpreted for me the other did not interpret for me.” This experience proved the truth of the maxim “all dreams follow the mouth”—that is, the meaning of a dream is what the interpreter says it is.

Of course, the Rabbis didn’t and wouldn’t apply the same principle to their own interpretations of the Written and Oral Torah, which are often just as conflicting. But thinking about Freud as a talmudist means thinking about the rabbis as Freudian analysts, and while the effect on both psychoanalysis and midrash is subversive, it isn’t necessarily destructive. Even if one can’t believe in the truth of the interpretations, is it is still possible to marvel at the creative power of the interpreters.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

Moses, Murder, and the Jewish Psyche

Sigmund Freud had always identified with Moses. At the end of his life, as the Nazis rose to power, he returned to the Bible and the origins of the Jewish psyche. We all know his scandalous theory—or do we?

(Almost) People

What does it mean to say that books have lives?

Lost in Translation

The novelist Jonathan Rosen has written evocatively of the parallels between rabbinic literature and the World Wide Web: “When I look at a page of Talmud and see all those texts tucked intimately and intrusively onto the same page, like immigrant children sharing a single bed, I do think of the interrupting, jumbled culture of the Internet.” Rosen’s insight is…

Scribes without a Torah

Julien Benda’s The Treason of the Intellectuals is one of those books that is famous even though no one actually reads it. Can it help keep those whose business it is to think in public on the straight path? Did it help Benda?

gershon hepner

NARCISSISM OF SMALL DIFFERENCES

Narcissism of minor differences, Freud claimed,

explains aggression between people who’re

alike but are because of likeness are so ashamed

that they declare their likenesses impure.

It’s only minor differences that stimulate

the Torah wars that lead to the halakhah.

The rationale of Torah wars is the debate,

some Talmud scholars general with a star,

while others are the infantry who follow

all arguments like orders, leading to

a peace of mind concerning laws they swallow

appreciatively, having thought them through.

That psychologic may establish peace of mind,

interpreting with Freudian psychoanalysis

the dreams of patients with solutions that unwind

the knotty problems in their memory palaces,

was a theory Joseph practiced in the Bible,

and echoes the interpretations of its text

by rabbis, although Freud did not find buyable

Jewish solutions for a patient who’s perplexed.

Sonja Trauss

Freud didn’t need to have actually studied the Talmud or zohar himself, if his father did, in order to absorb a rabbinic style of exegesis at home. Presumably, Freud heard his father talk and reason about … anything. And that’s a very obvious way of learning how to reason and interpret.