Legitimacy of Hope

“Israel’s legitimacy is a topic of dispute in the public square,” Ilan Troen notes, toward the conclusion of his new book, “and is likely to remain so.” In his own mind, however, this matter is certainly not up in the air. An American-born veteran Israeli, and one of the pioneers of Israel Studies, Troen has no personal need of a convincing justification for the existence of a Jewish state in the promised land. What he wants to do in Israel/Palestine in World Religions: Whose Palestine? is to shed some new light on the long-lasting non-theological discussions of the question embedded in his title by showing how bound up they are with even more ancient theological teachings.

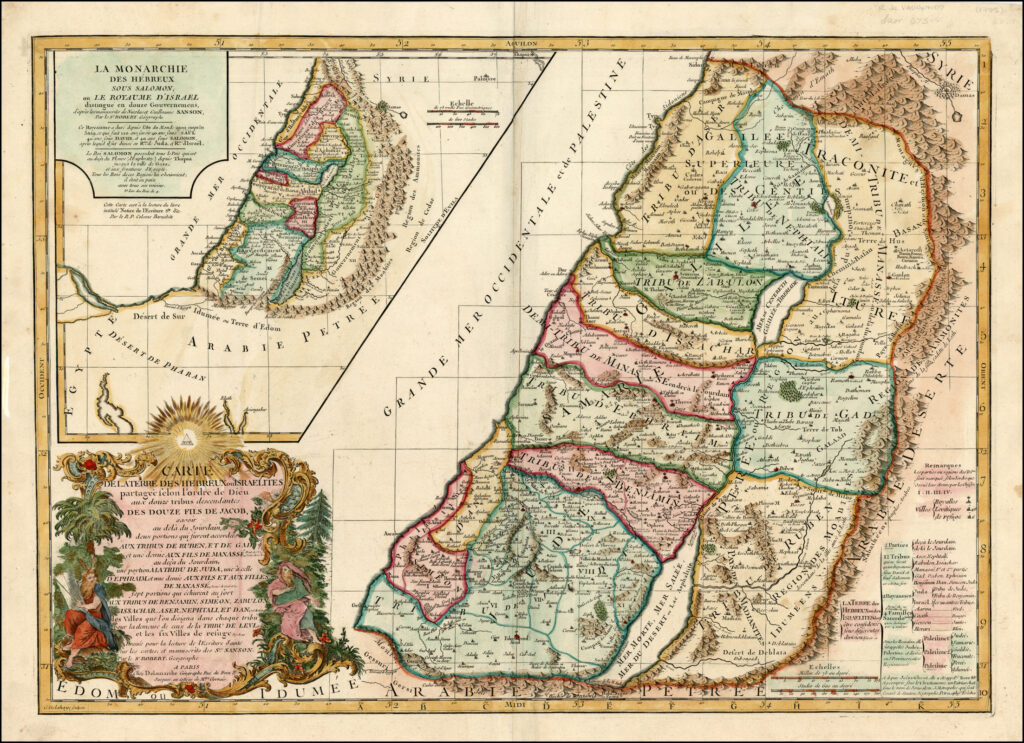

The secular debates that Troen reviews in the first part of his book center on the rights stemming from such sources as the act of conquest, the investment of labor in the land, and the history of Palestine. At the outset he reminds us of something that is often overlooked: the nations that won World War I not only redrew the map of the Middle East but were believed at the time to have had the right to do so. The victors were entitled to their spoils, everyone agreed, and the British therefore had every right to take over Palestine and to invite the Jews to create a national home within its borders. This right was only enhanced by the League of Nation’s adoption of “a mandate system to govern territories whose sovereignty passed from losers to winners in the Middle East, Africa, and islands in the Pacific.”

In this light, Troen briefly considers the role that the Jewish Legion played in the fighting in the Holy Land in 1917 and 1918. He does not claim, however, that the participation of Jewish soldiers, inspired by a dissident branch of the mainly neutral Zionist movement, in the conquest of Palestine endowed the Jewish people with any particular rights. He goes only so far as to say that whatever may have been “the actual impact of this modest fighting force on the course of the war and in Allenby’s campaign for the conquest of the Holy Land/Palestine, it has loomed large in Zionist history and lore and, certainly at the time, it enhanced the impact of the Balfour Declaration of November 1917.”

Indeed, in both World War I and World War II, “distinctive Jewish forces participated in both World Wars with the explicit intention of serving the creation of a Jewish state,” but this did not really establish their claim to one.

Unlike the Jews, the Palestinians could make no claim to have taken part in the British conquest of Palestine at the end of World War I. Yet they, like the Jews, initially “accepted the rights accruing to Britain as the legitimate successor to the Ottomans.” An exception to this rule was Henry Cattan, a Jerusalem-born Palestinian Christian jurist who wrote several books defending the Palestinian cause following its defeat in 1948. He relegated “conquest to a secondary right that is relevant only in special circumstances. In the case of Palestine, it does not supersede the rights of legitimate owners who have the right to take back their lands.” The authors of the PLO Charter followed in his footsteps.

In the twenty-first century, claims based on conquest are in ill-repute, but those based on the investment of labor have not been similar discredited. “Working the land was also a basic tenet of Zionism that granted the Jewish people title to Palestine.” But how much weight can be given to this Lockean argument when the Zionists had succeeded prior to 1948 in taking possession and working only “11.4 percent of non-desert area north of the sparsely inhabited Negev”? Acknowledging these facts does not, however, weaken Zionist claims, according to Troen. “The modest percentages of land registered to Jewish ownership create the impression of the massive superiority of Arab holdings. This illusion, often employed in polemics, implies that the remaining land was ‘Arab.’ That is a distortion. As indicated above, it was the state—Ottoman and then British—that had title to most of the land in Palestine and it had the right to dispose of untitled and unregistered land. Thus, the percentages owned by Jews was significant to enable partition into Jewish and Arab entities.”

In considering “claims derived from history,” Troen “examines how territorial rights are legitimated without reference to the presumed role of God in the past and to divine intentions.” He contrasts the Jewish claim, based on the Bible, with Palestinian claims, derived in part from the Hebrew Bible but founded in equal measure on the repudiation of its validity. Some Palestinians, for instance have proclaimed their people to be descendants of the Jebusites, a Canaanite tribe whose existence in Palestine prior to the arrival of the Israelites is known almost exclusively through the Bible. Others rely on the Danish “minimalist” school of biblical criticism, which maintains that “the Bible, from the patriarchs to the Exodus and through the Davidic dynasty, is a deceptive and calculated ruse.”

Troen doesn’t stoop to pick apart such canards. He is more interested in contesting another historically based claim, the currently “regnant, if not hegemonic, argument” that Zionism is nothing but a form of settler colonialism. The four pages in which he explains how “scholars and polemicists have wrenched out of context an exactingly developed colonial-settler analysis to describe a distinctive and different historical experience” constitute perhaps the most concise and cogent deconstruction of this unfortunately fashionable accusation now available in print. Yet Troen doesn’t delude himself into thinking that “the misapplication of the colonial-settler pattern to Israel” or any other challenge to the legitimacy of Zionism can be deflected through argumentation.

The imperviousness of Zionism’s antagonists to any reasonable defense of it, he maintains, “suggests that challenges to Israel’s legitimacy cannot be understood as stemming solely from secular principles discussed in preceding chapters.” To fully grasp why this is the case, Troen maintains, one has to turn to “primary challenges embedded in theological discourses about Jews and Jewish sovereignty in the land once termed ‘Judea,’ and God’s promises that remain part of the cultural legacy that is the inheritance of the modern world.” I have my doubts about the extent to which he has proved his point here, but what he has to say about the theological dimensions of anti-Zionism is certainly worthy of attention.

Some of the challenges to Israel’s legitimacy stem from the Jewish tradition itself, as Troen reminds us in his thorough review of the spectrum of Jewish religious stances with regard to Zionism. But he doesn’t assign any real weight in the contemporary world to ultra-Orthodox denunciations of Zionism as a usurpation of the messiah’s task, nor does he seem overly concerned about the universalist strains of Reform theology that have long been hostile to Zionism and are, as he acknowledges, undergoing something of a revival. His real focus is on what he calls “the two main streams of monotheism,” Christianity and Islam, according to whose “historic doctrines, the (possibly) miraculous return of Jews to reclaim and rebuild their ancient homeland should never have happened.”

In his chapter on Christianity’s claims, Troen quickly and effectively sketches the story of Christian supersessionism, which delegitimated Judaism as a religion along with any Jewish claim to the Holy Land. He demonstrates that this doctrine underlay the Catholic Church’s initial opposition to Zionism but didn’t prevent it from ultimately recognizing the existence of the State of Israel. Nevertheless, even when it did so, it did not “acknowledge the legitimacy of the State of Israel as a Jewish state. It merely affirms the presence of Jews.”

Among Protestants there has been more variety as well as a lot of enthusiastic support for Zionism, above all among Evangelicals, whose eschatology carves out a special place for the State of Israel, but also among liberals, like Reinhold Niehbur, whose “pro-Zionism did not stem from the expectation that a Jewish state was part of God’s plan in the pre-millennial age” but was essentially humanitarian. Unfortunately, the tide seems to be turning against this sort of thinking. “In 2014,” for instance, “the Presbyterian Church issued a dramatic repudiation of Niebuhr in secular terms in Zionism Unsettled: A Congregational Study Guide, a text proposed for religious instruction. Representing a paradigm shift, the guide to understanding Zionism culminates in a scathing critique of Niebuhr. Much of this document argues that Israel is a classic colonial-settler society and as such, illegitimate.” But that is not all. Following in the footsteps of the Palestinian Anglican theologian Naim Ateek, it explicitly espouses supersessionism. This turnabout “suggests,” in Troen’s opinion, “that post-war support for Israel in some mainline Protestant churches and their rejection of supersessionism may not be enduring.”

Contemporary Christianity is anything but monolithic in its view of Zionism and Israel and there are, Troen hastens to note, countervailing and encouraging trends, even within the Christian fragment of the Arab world. There is no comparable diversity within Islam, however, “which has been far more unified in its opposition to Zionism than Christianity.” Troen’s capsule history of the domineering relationship of Islam toward Judaism effectively covers all of the ground between the Qur’an and Hamas, demonstrating the deep roots and abundant fruits of Islamic resistance to Zionism and hatred of it.

It is impossible to read this section of the book without recalling how recently the author himself has personally borne the burden of this enduring hatred. Israel/Palestine in World Religions is dedicated to his daughter and son-in-law, “murdered by terrorists while defending their family Kibbutz Holit on the Gaza border Shabbat morning, 7 October 2023.” It would be entirely comprehensible if Troen had published in the aftermath of the hideous events of that day a book which completely reciprocated the hatred put on display by Hamas. But that is not what he has written. As insistent as he is on elucidating the full magnitude of Muslim anti-Zionism, he does not surrender to the idea of its inevitability.

Troen sees some grounds for optimism even within the Muslim world, such as the Northern Branch of the Islamic Movement in Israel, led by Mansour Abbas. Granted, this movement has so far fallen short of acknowledging the legitimacy of Israel as a Jewish state, but its pragmatic readiness to participate in Israel’s politics and government is nevertheless promising. According to Troen, this flexibility “suggests that in Islam, as among other monotheistic creeds, theologies are mutable or multiple, and that it depends on the believer to choose among the rich possibilities of the faith.” In holding – albeit tentatively – onto the hope that Muslim believers may someday make better choices, Troen, a tough-minded man, is evidently doing his best to follow in the footsteps of his deceased daughter and son-in-law who, as he says in his dedication, pursued in their lives a path of “mutual understanding and accommodation” with the Muslims among whom they lived. How correct he is to do so remains to be seen.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

Kidnapping History

Did the Ashkenazi elite of the early State of Israel conspire to systematically kidnap Yemenite Jewish children?

The Best Unicorn

Peter S. Beagle's classic fantasy novel The Last Unicorn perhaps betrays its Jewish bent with "idiosyncratic yet archetypal characters such as the hapless magician Schmendrick."

Going Public

The Jewish Jane Austen, or better?

Kibbutz Be’eri, Chaos, and Creation

"Be’eri was not so much assaulted as disemboweled. After the massacre there were corpses everywhere—what is left now is the stuff of lives ripped out."

gershon hepner

INTELLECTUAL SLOVENLINESS

OF ANTI- ZIONISTS IN ELITE UNIVERSITIES

I wonder whether the toxicity of intellectual slovenliness

that led to the anti-Zionistic protests in American universities that are elite

might correlate with approval of halakhically-contrary dovenliness

reflected by reluctance of the slovenly their prayers thrice daily to repeat,

their slovenliness a fatal, fetal bun that should be banned while in the oven

of people who’re so slovenly they do not to the shomer who is never sleeping daily daven.

David Z

I guess I need to read the book, but as to Islam, I understand Dar el-Islam, but there seems to be something worse to modern Muslims about Israel than about Spain or Bulgaria. Is it just the freshness? Because while the Quran recognizes that the Jews are indigenous to Israel it doesn't mention the Spaniard or Bulgarians at all. So why do the Jews get this erasure treatment rather than the general it's sad that Israel isn't under Muslim sovereignty but that's how it is for now. Or maybe that is the attitude--look at Egypt, Jodan and the Gulf States. And why did Saddam Hussein, an atheist, get a pass?