Kibbutz Be’eri, Chaos, and Creation

On Tuesday I drove from Jerusalem to Be’eri, a couple of miles from Gaza. Some journalists and I walked around the kibbutz for two hours. I couldn’t hold a pen steady enough to take notes, but I did think about the most frightening phrase in last week’s Torah reading, maybe in the whole Tanakh: tohu v’vohu, referring to the chaos before creation.

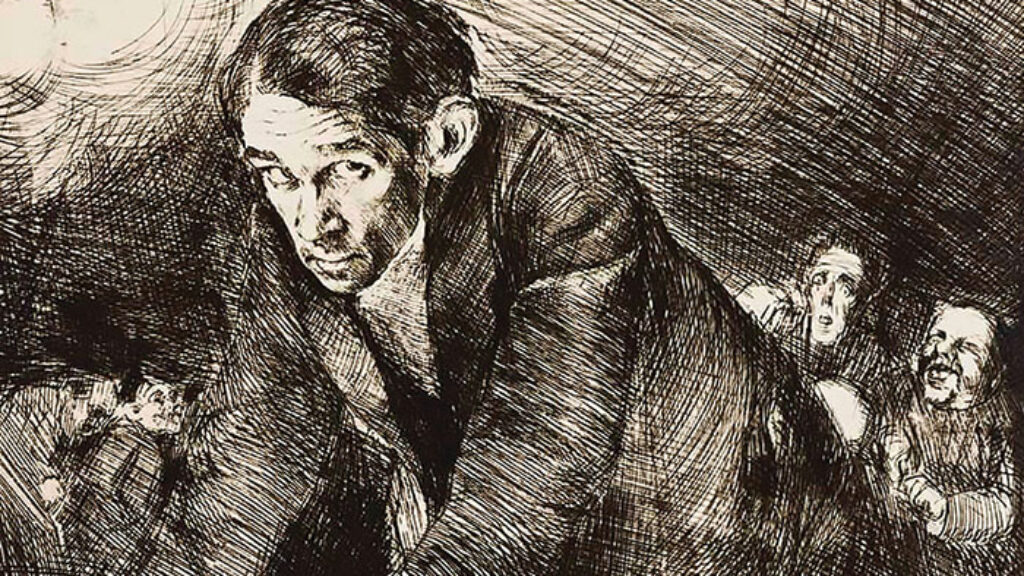

Out of the void, God forms a cosmos from light, dark, land, sea, plants, and animals. Crowning it all is the human being, who can imitate the Creator by making all sorts of wholes, new unities that are held together and ordered to a purpose. God’s choice to raise a universe out of chaos implies that chaos remains a possibility. Order is not given, it is made. It can be unmade. A created thing can lapse or be reduced into the welter and waste—as Robert Alter renders tohu v’vohu—of uncreation.

This kibbutz was, for many decades, a human whole with a human purpose. The central fact about places like Be’eri is that public life is conducted right next to private life, which is to say there is very little privacy. Not no privacy—there aren’t children’s houses like in the classic kibbutzim. But space is not plentiful, and so is assigned to each function of human life according to its need. Be’eri has small family homes right next to its kindergarten, right next to offices, right next to the communal dining area. Nothing sprawls. Everything is contained and everything is close. A claustrophobic blessing.

And in the hands of wicked men, a curse of the same sort.

Be’eri was not so much assaulted as disemboweled. After the massacre there were corpses everywhere—what is left now is the stuff of lives ripped out.

A communal building in the middle of the kibbutz was burned, the blackened light fixtures, metal ceiling frames, and ashen residue of floors now intrude onto the sidewalk. Walk just a few feet more—some banged-up motor bikes. A bit farther, down and to the right—a playground has been torn apart, its bits of plastic mixed in with bits of concrete from the blown-up school building. Colored sheets of laminated paper (intact, somehow) printed with a bold aleph-bet. Seared business papers and coloring books, markers without caps. Thirds of pens, glass, and rubber, and insulation, and wire, and vinyl, and Velcro, and all these parts of things that had their times to be used and their times to be put away. What used to live on shelves and in drawers and inside ceilings and walls is spilled out and mixed up.

A little farther. The exterior of a house—it looks like a house, but the IDF spokesman says he isn’t sure—is punctured by about a dozen bullet holes. One wall, in the front hall of a home, is still splattered a dark scarlet about a foot of the ground. Little bookcases with books. Bedrooms and kitchens, ruined. Behind a torn screen inside a broken window, two benches with stuffed animals—a panda, an elephant, and there’s a little green frog on top of a bin of toys. I’m sure I have that same elephant at home.

The Hamas pogromists destroyed whomever and whatever they could, and then they destroyed the next line of defense—those who came to cure and to protect. A sweat-stained bulletproof vest has been discarded on a lawn. Next to the incinerated cars is a blood-pressure cuff, the dial covering cracked. There are useless guns, and emptied magazines, and shell casings on benches and on the ground. At the front door of one house lays an oxygen mask without a tank.

The slaughter on Shemini Atzeret has been compared to massacres by the Nazi Einsatzgruppen eight decades ago. It was indeed the largest episode of Jew-murder since the Shoah, but I suspect the deeper reason for the comparisons is agony that Jews were, for a few hours, nearly as helpless before their enemies as they were in the years just before the Jewish state.

But standing in Be’eri I noticed—to be exact, I heard—the one difference that makes all the difference. The major sites of Jewish death in eastern Europe are silent except for the day school, yeshiva, and seminary students on pilgrimages to desolation. I was such a student about ten years ago, and I remember feeling some embarrassment at the whole thing. I was a visitor in the land of the dead. They had nothing to say to me, nor I to them.

But Be’eri is loud, terrifically loud. The Iron Dome bangs seven or eight times in a half hour. On my imprudently fast drive out of the area, a missile alert siren sends me and other motorists out of our cars and onto the ground, and three more shots roar from the Dome’s launchers (“Don’t worry, it’s nothing” says the middle-aged sabra crouching next to me). Israel’s infantry and armor are encamped in Be’eri and nearby. The shtetls of Poland are abandoned. The kibbutzim are now defended.

At some point, Be’eri will be inhabitable again, and some of its people will return. To return is not to restore. The murdered will stay murdered. Many who survived and fought will find their former home to be an inviolable zone of horror to which they cannot come back. I expect it would be that way for me.

And I also expect Israeli society to avenge this kibbutz’s degradation into welter and waste by building it anew. In a year I’ll come again. The debris will be gone and the dead will be memorialized. Those who lived here once and want to settle here again will likely be joined by others, and Be’eri will once more be a land of the living.

Suggested Reading

And the Heart Is Forever Broken

Amid the ferment of interwar Poland, two opposite motions guided Jews who followed the sometimes blinding torches that lit the way toward modern culture. The first surged outward. The second traveled inward.

Purim at JRB

This Purim at the Jewish Review of Books, we’re turning things a little upside down. A Jewish review of books? Why stop there? We’ve collected three fun and funny reviews…

Yo’s Blues

For Israeli artist Yoram Kaniuk, the bohemian world of Billie Holiday, Marlon Brando, and James Agee had a lot to offer, but not enough.

Eichmann, Arendt, and “The Banality of Evil”

Richard Wolin’s review of a new book about Adolf Eichmann caused a stir, mainly about Arendt. His exchange with Seyla Benhabib on the banality (or not) of evil.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In