Days of Redemption

From the moment Zionism began, spokesmen for traditional Judaism denounced its leaders as sinners trying to usurp the role of the as yet unsent messiah. That charge has largely disappeared, but the historical question of whether Zionism should be seen as the abandonment of messianism or its descendant is still with us. At first glance, Arieh Saposnik’s Zionism’s Redemptions might appear to be part of this discussion, but it isn’t, exactly. Saposnik acknowledges that the messianic idea is one of the sources of the “redemptive thrust” of Zionism, but he is especially interested in exploring “redemptive motifs . . . in less immediately obvious corners of Zionist thought and the Zionist project and among thinkers and actors who are less immediately identified as looking toward the redemptive.”

Instead of beginning with an obvious text such as Herzl’s Altneuland (which he refers to only once in passing), Saposnik commences with the once-famous British author Israel Zangwill. A very early Zionist, he abandoned the movement in 1905 after it turned down the British offer of Uganda as a Jewish homeland. He is usually thought of as a man focused more on locating a refuge for Jews somewhere, anywhere, than in bringing about some kind of deeper transformation. But Saposnik shows that even here, in Zangwill’s pragmatic offshoot of Zionism, the distinction between a mundane political movement and a more spiritualized one is not that clear-cut. Zangwill’s territorialism aimed, Saposnik explains, if not exactly at redemption then at what he explicitly called the “salvation” of the Jews. This was wrapped up in a vision of universal redemption, which included, as Saposnik writes, a “revived Jewish nation embedded in the rest of humanity in a geographical sense as well, without predetermined geographical limitations.”

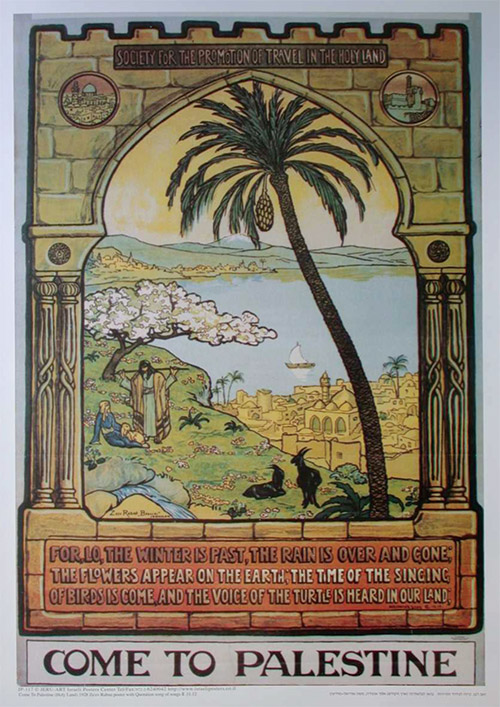

Saposnik is as interested in pictures as he is in words. He highlights, for instance, the early-twentieth-century Zionist artist Ephraim Moshe Lilien’s depiction in “Passah” of Zion as “a distant, almost mirage-like, promise in the far-off eastern sunrise, while the current reality is that of a despondent, mournful Jew entrapped in thorny barbed wire” against the backdrop of an unmistakably Egyptian landscape. But references of this sort to Israel’s emergence from slavery soon fell out of fashion. During the initial decades of Zionist settlement, Saposnik tells us, the “reading—and rewriting—of the Exodus was less amenable to Palestine’s version of redemptive nationalism” than later stories of the ancient Jews’ military valor.

Things changed somewhat at the beginning of the 1930s, with the “growing ubiquity” in the Yishuv “of the Exodus as a paradigm.” The kibbutz movement, in particular, began to produce new secularist haggadot that celebrated liberation without thanking God for it. In these texts and the accompanying rituals, “the Exodus itself, the desert, the wandering, are often all but absent.” What they stress, instead, is not the process of redemption but the Land of Israel and “the Zionist project as the redemption that is the end of the process.”

Nahum Sokolow had a lot to say about the process of redemption. A central figure in Zionist diplomacy during World War I and later head of the World Zionist Organization, Sokolow scarcely appears in previous discussions of Zionist ideology. Yet he was throughout his life a literary man, a longtime Hebrew newspaper editor who wrote, among other things, one of the first histories of Zionism. He published it in 1919, in what Saposnik aptly calls “the heady, post-Balfour days,” when “redemption” was a catchword.

A thoroughly secular Jew, Sokolow nevertheless had no compunction in arguing that “Zionism is the direct heir to the biblical promise and to Jewish messianic expectations.” What distinguished it from earlier Judaism, he believed, was its activism. And the “first to transform traditional messianic longing into the makings of modern politics or, in a word, into modern Zionism” was, in Sokolow’s eyes, not Herzl or any other nineteenth-or twentieth-century figure; it was the seventeenth-century Dutch rabbi Menasseh ben Israel. Sokolow argued that Menasseh’s famous attempt to further the admission of Jews into England was intended as a step toward his messianic vision “of an ultimate Jewish return to the Land of Israel.”

Sokolow posthumously recruited not only Menasseh but many of his Christian contemporaries in England and, for that matter, their descendants into Zionist ranks. In the seventeenth century, he says, English Protestantism desired no less than Menasseh to see the ultimate restoration of the Jews to Palestine and provided “the earliest stimulus to Zionism.” The nineteenth-century fusion of this enduring “restorationist-redemptive motivation” with an “imperial impulse” (in Saposnik’s words) magnified even further Britain’s interest in Palestine. Sokolow also assigned the French a supporting role, highlighting Napoleon’s offer to the Jews of the East to help them return to Jerusalem. In his overall view, however, “the stress . . . remains on England,” which, on the verge of the 1919 Paris Peace Conference, where the fate of Palestine was to be decided, was possessed by “a vision of a liberal imperialism in which Britain is cast as the principal agent of civilization and progress, of which the Zionist idea is perhaps the clearest and most path-breaking expression.”

But what was the relationship between Jewish messianism and Sokolow’s progressive understanding of redemption? Sokolow wrote reverently of the ancient vision of an “Ideal State,” in which “the King was the earthly viceroy of the invisible sovereign.” Of course, his own “modernized and secularized translation of the biblical God” kept him from hoping for a restoration of a theocracy. Instead, as Saposnik writes:

Sokolow recasts the notion of loyalty to God and His moral imperative as pointing to a redemption that is a rediscovery and reclamation of an authentic self. “National righteousness,” he explains, “consists in the possession of a reverent spirit and the practice of justice, purity, and mercy.”

Saposnik sums things up by noting that for Sokolow, redemption was “rooted in authentic selfhood, and that authenticity is itself rooted in loyalty to the nation, which is in some respect the manifestation (or replacement?) of God in the modern world.” Zionism’s highest goal, the regeneration of the Jewish people, its return to itself, was not, in Sokolow’s eyes, a merely parochial concern but “a constructive task of the highest value from the point of view of humanity.” Despite the secular translation, an awful lot of the spirit of Jewish messianism remains in this redemptive vision.

Sokolow was far from the only Zionist pondering redemption at the end of World War I or attempting to act it out. After the League of Nations ratified the British Mandate over Palestine, “a ‘week of redemption’ was declared in Palestine and throughout the Zionist world.” In the 1920s, November 9 became a holiday in the Yishuv, “Redemption Day,” marking General Allenby’s entry into Jerusalem as well as the Balfour Declaration. Many parents in Jewish Palestine named their girls Geulah (redemption) and their boys Yigael (he will redeem).

Up to the very end of his book, Saposnik writes as an Israeli scholar demonstrating some of the ways in which early-twentieth-century Zionists were imbued with exalted—but nonmessianic—visions of a better world and acted on the basis of them. In a postscript, however, he ventures, with some trepidation, beyond the role of the objective historian. Two things bother him about the present moment. One is the way in which messianic religious Zionism, a minor factor during the period he has examined, has more recently become “a powerful force in Israeli society, largely replacing the visions of redemption discussed in this book, which, it seems, underwent a process of decline and retreat.” The other is the extent to which Israelis, as well as others, are “caught up today in a post-truth, post-ideology, and post-vision world.” Between the dangerous and increasingly dominant version of messianism and the cynical rejection of any vision of redemption, Saposnik believes, there is a need for an alternative.

Zionism gave birth to a number of them, once, that drew on Jewish tradition as well as other sources. And it is Saposnik’s “hope that recapturing a picture of some of the ways in which I believe Zionism sought to piece together such an expression in the twentieth century, however imperfectly it may have done so, might be instructive both for Israelis and for others around the world” who face similar dilemmas.

This is not too much to hope for, but how much instruction can such a picture—even one as attractive as the one Saposnik draws—provide? For those who are under the sway of a far more colorful religious vision, it is unlikely to have much of an appeal. Nor can it provide much guidance for those who are thoroughly ensconced in a “post-truth, post-ideology, and post-vision world.” But even those who haven’t given up on the search for truth need something more than a historical picture. They need an argument that persuades them that the picture they are looking at is rooted in the truth and represents the good. Saposnik knows that this isn’t what he has done, but he hopes nonetheless that our present historical moment is not irredeemable and that his evocative exploration of overlooked corners of the Zionist past may help those who have lost their way.

Suggested Reading

“A Story of Commitment, Solidarity, Love Even”

Retracing her father’s wartime journey from Poland, across the USSR, through Iran and eventually to Palestine, Michal Dekel learns a lot about what it means to belong to a people.

Where To: America or Palestine? Simon Dubnov’s Memoir of Emigration Debates in Tsarist Russia

Dubnov's magisterial autobiography, written while Dubnov was in exile from both the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany, takes the reader on a deeply personal journey through nearly a century of upheaval for the Jews of Eastern Europe. A new translation.

Lands of the Free

It is sad to watch the territorialists engage in their wild goose chases all over the globe at a time when multitudes of Jews were in need of a place, any place, to go.

The Rebbe and the Yak

What do you do when your ancestor appears to you in a dream saying that he is trapped inside the body of a Tibetan yak? If you're the Ustiler Rebbe in Haim Be'er's new novel, you go to Tibet to find him, of course.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In