Time Ticks Away in Portugal

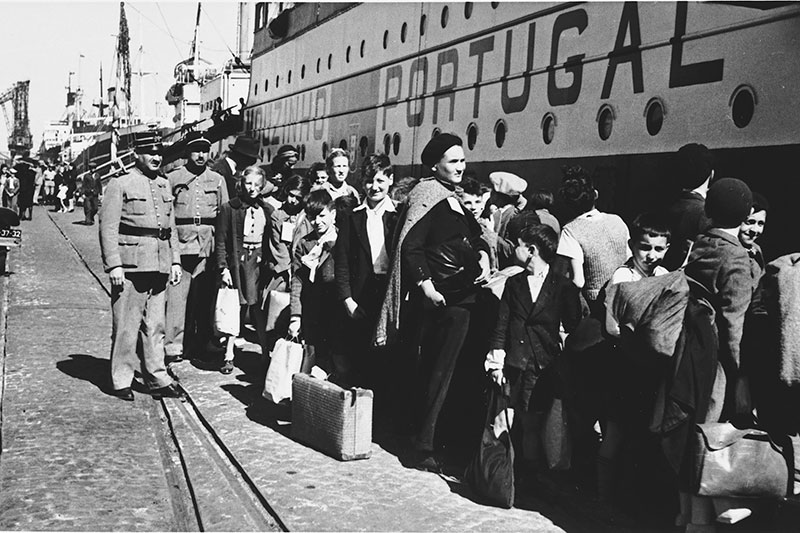

Compared with every other country in Europe, Portugal was a haven for Jewish refugees during World War II. It was often a land that they had to sneak into illegally, with false papers or at night, via dangerous mountain paths, but once they were there, they were more or less safe. Yet they were also unwanted and were prodded to leave as soon as possible. They had every incentive to do so, but getting out was often as difficult as getting in. And surviving while stuck there could be a tricky business.

Portugal was in those days an authoritarian state but far from the worst. Indeed, Life magazine called its ruler, António de Oliveira Salazar, “the world’s best dictator.” He was a determined autocrat but not an antisemite. Portugal’s very small and then only recently reestablished Jewish community possessed the same rights as the country’s other citizens. It retained them throughout the period when other, similar regimes curtailed Jewish rights to curry favor with the Nazis. Still, Salazar didn’t want more Jews settling permanently in his country and intentionally gave the refugees who passed through Portugal during the war a hard—but not impossible—time.

In Hitler’s Jewish Refugees: Hope and Anxiety in Portugal, the distinguished historian of modern German Jewry Marion Kaplan is less interested in the treatment accorded to Jews for whom Portugal was such a difficult way station than in recording what the experience felt like to them. This is admittedly a difficult thing to do. For large numbers of them, the central fact of their lives was the struggle to obtain the documents that would enable them to continue their migration, and as one of the refugees she quotes said, “It would have taken the pen of a Kafka . . . to depict the world of visas in all its surrealistic absurdity; that of a Dostoyevsky to render the nightmare of the petitioners’ struggle for survival.” Kaplan is a historian, not a novelist, but she draws on many gifted writers who were themselves on the scene to enrich her own sensitive account, which is based largely on memoirs and neglected or undelivered letters that she discovered in institutional archives. In doing so, she shines a bright light on what was far from the worst corner of the Holocaust world and a place that is, for that very reason, more accessible to us. It is certainly haunting enough.

Tens of thousands of Jews made their way into Portugal in waves between the fall of France in 1940 and the end of World War II. The ordeals Kaplan depicts were not terribly long, but to the people who endured them, they often seemed endless. Things might have been different if they had been allowed to work, but most of them were not. This prohibition had the beneficial side effect of preventing the Portuguese people from resenting their competition, but it left the Jewish refugees poor and despondent.

Some, such as the not-yet-famous thinker Hannah Arendt, were lucky enough to be able to leave for America quickly. The rest would have been happy to go anywhere, especially before November 1942, when the Allies landed in North Africa and the danger of German invasion of Portugal seemed to dissolve. But to get out, one needed the right kind of papers, and to obtain them was a struggle that usually required excruciating negotiations and large sums of money—and the clock was always ticking. Portuguese law permitted Jews to stay in the country for only 30 days, though it wasn’t strictly enforced. Those in violation were sometimes imprisoned, sometimes expelled from Lisbon and confined to small villages, and sometimes left to live in uncertainty as they ceaselessly struggled to find a way out.

These facts are known, if not terribly well remembered, but Kaplan wants us to understand what it felt like to be a Jewish refugee. She tells us what these people wore and ate, where they rented their homes, how they interacted with their Portuguese neighbors and the local Jewish community, and about their connections with foreign Jewish welfare organizations and foreign bureaucrats, their fears and dreams, and much else. She is equally skilled at evoking the feelings shared by large numbers of the refugees and those of specific individuals.

Portugal was a beautiful and relatively tranquil place, and some of the refugees were immensely relieved to find themselves in what they called a paradise, or at least “the first place that was normal.” For others, however, like the novelist Alfred Döblin, it was impossible to relish being there. “We couldn’t enjoy it. We could only think of what we had left behind.” Among the worst things, for those who were out of funds, was the feeling of being utterly déclassé. Hannah Arendt described “a frustrated middle-aged man who had appeared before countless aid committees ‘in order to be saved,’” lamenting that “‘nobody here knows who I am!’ Nobody knew who he had been, or the kind of people he had come from, or the heights from which he had dropped.”

Aid was available, both from the very small but admirably generous local Jewish community and international Jewish organizations, mainly the Joint Distribution Committee, but also from US-based Quaker and Unitarian charities. It was, however, necessarily far from lavish and usually accepted by formerly independent people with deep misgivings. But often enough, they had no other choice unless they could obtain money from friends or relatives abroad.

Kaplan tells the story of Kurt Israel, a young German-born and German-educated former law clerk who had lived in Holland until the Nazi invasion in May 1940. He was lucky enough to make it to Portugal as part of the fleeing entourage of his employer, Uruguay’s ambassador to the Netherlands. Lucky once again, he found inexpensive lodging in Lisbon with a German Jewish couple; the wife was from his mother’s hometown and knew her. “‘In all other respects,’” he wrote in his memoir, “‘I could and would have enjoyed my stay in Lisbon,’” but his inability to work and his “‘uncertainty concerning [his] future’ made ‘any real enjoyment impossible.’”

Israel had a brother in the United States whom he desperately tried to join. Every time it looked as if he was on the brink of success, the American consulate placed a new obstacle in his path. For months he had to juggle his attempt to obtain an American visa with applications to extend his stay in Portugal, as he worried about being apprehended by the police. While decrying the “lazy vacation-life that was slowly but surely getting on [his] nerves,” he played bridge and worked on his English. Eventually, he began to suspect that the American consulate was intentionally making things difficult for him, constantly moving the goalposts. And he was right. Israel was the unwitting victim of the policy of “postpone and postpone and postpone” introduced by the infamous assistant secretary of state Breckinridge Long.

Whether because the Uruguayan ambassador had put in a plug for him or because his brother’s employer in the US had filed a “moral affidavit” for him or because a different American official interviewed him, he finally got his visa at the end of December. On January 27, 1941, he boarded a ship for New York. “Never mind,” he recorded, “that I travel fourth class and share my quarters with some 80 seasick people—I am on my way!”

It took somewhat longer for Miriam Stanton to get on her way. A Polish-born woman living in German-occupied Paris, she escaped in March 1941. She was soon engaged in a daily routine of “visiting the English and Polish consulates, telephoning her parents, stopping at the post office to check on the elusive visa” that would enable her to rejoin her fiancé in England. Like many of the refugees profiled in Kaplan’s book, she began to hang around Lisbon’s cafés, which became a kind of home away from home for her. In the café located seven floors below her room in a walk-up building, she attended a Passover Seder. “When the man leading the ritual arrived at the traditional question, ‘Why is this night different from all other nights?’ spoken in Hebrew, he broke down and cried. He had lost his wife and only child. In trying to console him, the group grew closer to one another and, for that moment, ‘felt like a family.’”

Toward the end of November 1941, Stanton and many of the Polish Jews in her ersatz family (like most refugees in Lisbon) received letters from the government warning that they would be transferred to a “forced residence” unless they left Portugal within two weeks. Sitting together at the café, they dreamed up the idea of sending a birthday telegram to Winston Churchill, “begging him to send us to any country in the world under the British flag.” Then they went together to the post office and sent it. Amazingly enough, it seemed to work, or at least coincided miraculously with some lucky developments. Thirteen days afterward, the group was called together by the Polish consul and told to pack for Jamaica. The Joint Distribution Committee would pay for their trip and their stay. They left in January 1942. Miriam Stanton spent the rest of the war on the island and, after a seven-year separation, rejoined her fiancé in England.

In her preface, Marion Kaplan describes her discovery of a large trove of unopened letters to and from refugees in Lisbon during World War II at the Museum of Jewish Heritage in New York. This opened up a story that deserved to be recorded for its own sake, but that is not the only reason Kaplan has told it. “I wrote this book,” she says, “while tens of millions of refugees were fleeing recent and ongoing wars, terrorism, and economic catastrophes.” She is acutely aware of the mistreatment of these people, by the United States and other countries, and hopes, with good reason, that readers of this volume will learn from it how to “listen compassionately to refugees’ stories in our own time.”

Suggested Reading

Faith in Princes

That FDR could have done more for the Jews in the Holocaust has long been known, but have we fully understood how much his inaction sprang from his own antisemitism?

“A Story of Commitment, Solidarity, Love Even”

Retracing her father’s wartime journey from Poland, across the USSR, through Iran and eventually to Palestine, Michal Dekel learns a lot about what it means to belong to a people.

Power and the Voice of Conscience: A Lost Radio Talk

On January 19, 1947 a young rabbi named Emil Fackenheim got behind a microphone to give a searing radio address about the Jewish refugees from Europe. He himself had been one only four years earlier.

Where To: America or Palestine? Simon Dubnov’s Memoir of Emigration Debates in Tsarist Russia

Dubnov's magisterial autobiography, written while Dubnov was in exile from both the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany, takes the reader on a deeply personal journey through nearly a century of upheaval for the Jews of Eastern Europe. A new translation.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In