Faith and Miracles: Hasdai Crescas’s Passover Sermon

Sometime near the turn of the 15th century in Saragossa, perhaps for Shabbat ha-Gadol (the Sabbath preceding Passover), Hasdai Crescas composed a sermon that anticipated his later groundbreaking philosophical work. Crescas, who had by then been appointed chief rabbi of Aragon by King Joan I and Queen Violant de Bar, began his sermon with a quote from the first mishnah in tractate Pesachim: “On the evening of the 14th [of Nissan] we search for leaven by the light of a lamp.”

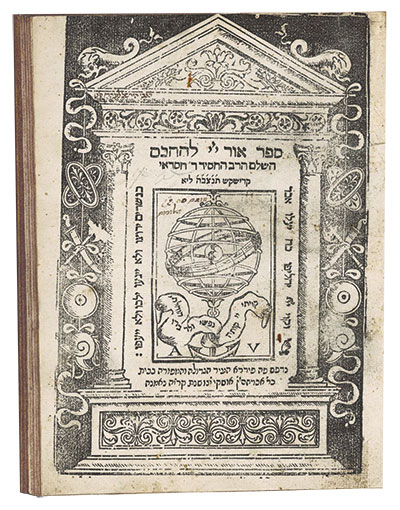

The imagery of light and lamp was important to Crescas. In his classic Light of the Lord, which he published near the end of his life in 1410, he wrote, “The relation between the ground for a commandment and the commandment itself is one of light to lamp, as . . . Solomon said, ‘For a commandment is a lamp; and Torah is light’ (Prov. 6:23).” This book, which is often described as the last great work of medieval Jewish philosophy, was an attempt to illuminate that ground by refuting Maimonides’s Aristotelian reconstruction of Judaism and restoring what he saw as authentic Jewish tradition. In his brilliant critique of Maimonides, Crescas replaced the self-intellecting intellect that was Aristotle’s God with the God of Israel, whose essential nature, he argued, was one of unbounded and unfailing love.

Although Crescas’s arguments in Light of the Lord were the intricate work of a philosophical master craftsman, his conclusions spoke to the urgent needs of an imperiled Jewish community. In 1391, the Jews of Barcelona fell victim to horrific anti-Jewish riots, which quickly spread, leaving thousands of Jews dead, including Crescas’s only son. Approximately 150,000 Jews converted to Christianity, most by force or out of fear. Although Crescas’s royal patrons were able to protect the Jews of Saragossa, Barcelona’s thriving Jewish community, where Crescas had grown up and studied under the great talmudist Rabbi Nissim ben Reuven Gerondi, was destroyed, as were two other major centers of Jewish life, Valencia and Girona.

Crescas’s most direct intellectual response to these events was his book The Refutation of the Christian Principles, which methodically contested the Christian views of original sin, the Trinity, the virgin birth, and seven other Christian dogmas. However, his arguments for a God of infinite love in Light of the Lord and his profound explorations of the nature of faith were also responses to the crisis through which he and his community lived—and some of them, especially those concerning faith, were first worked through in his Passover sermon.

The sermon was discovered by Hebrew University professor Aviezer Ravitzky in the manuscript collections of Harvard and the Vatican. At Harvard’s Houghton Library, it was found among sermons written by members of Crescas’s circle. In the Vatican library, it was bundled with the philosophical-kabbalistic sermons of the 15th-century thinker and poet Rabbi Michael Balbo ben Shabtai Hacohen of Candia (Crete). Recognizing the Passover sermon’s distinctiveness and the undeniable resemblance between its ideas and those of Light of the Lord, Ravitzky convincingly identified it as the work of Hasdai Crescas and published it in 1988.

Although Crescas’s sermon is not long, it is complex, and it covers, as Shabbat ha-Gadol sermons classically do, both halakhic topics and theological ones. The questions that drive Crescas’s reflections concern the nature of faith and its relation to the miraculous story of Passover. Three questions in particular preoccupy him: Does belief generally involve an act of will? What role do miracles play in faith? What role does the human will play in faith? Crescas treats these questions not solely philosophically but from a Jewish perspective as well.

The most trenchant argument for the position that the will does have a role in belief is that it would be unfair for God to reward and punish us for our beliefs (as the Torah and the Rabbis imply that he does) if they are not ultimately within our control. The core argument against this position is that if one can will one’s beliefs, then there is no check on what one might believe. Crescas reaches the conclusion that we are not free to disbelieve what is either patently obvious to us or the result of sound demonstration. Proof, for Crescas, is quite literally compelling.

And what about miracles? Do they compel belief in the same way that an airtight philosophical or scientific argument does? Not necessarily. According to Crescas, the various miracles that Moses performed were aimed at specific doubters. Thus, the miracle of his staff turning into a snake was aimed at convincing first himself and then the Israelites that he was truly God’s emissary; the 10 plagues were obviously aimed at Pharaoh and the Egyptians. And yet, since miracles can be suspected either of being the result of sorcery (the first two plagues—blood and frogs—were, after all, replicated by the Egyptian sorcerers) or of having been somehow performed through natural means, they do not instantly or inevitably compel belief. However, even a miracle that clears these hurdles lives on only in the memory of those who witnessed it, and even there, it fades. Unlike a sound argument, it cannot be repeated.

No miracle, no matter how convincing and how ineluctably ascribable only to God, Crescas argues, induces permanent belief. Although the Torah says after the splitting of the sea that the people “believed in the Lord and in his servant Moses” (Ex. 14:31), it does not say that they became believers for life. Only at the revelation at Mount Sinai does the Torah say, “And they will believe also in you [Moses] forever” (Ex. 19:9): the revealed Torah bears constant and enduring witness to the revelation. This leads Crescas to an insightful thought about Passover in relation to Shavuot, the next major holiday on the Jewish calendar. Since Shavuot celebrates the receiving of the Torah, which was the culmination of the exodus and miracles that first inspired the Israelites’ faith in God and in his servant Moses, it follows that Shavuot is in a sense continuous with Passover. This is the deeply theological reason that the two holidays are ritually linked by the counting of the 49 days of the sefira that lie between them.

Crescas’s final problem concerns will and religious faith. If arguments, miracles, and prophecy (as represented by the revelation at Sinai) can all override a person’s will and compel belief, then why should one be rewarded for believing and punished for failing to do so? After all, it is not a matter of choice.

Crescas’s answer to this question is subtle: we cannot will ourselves to believe, but we do choose how we believe—we may be joyful or resentful; we may diligently seek to understand what we believe, or we may want nothing to do with it:

Since the miracle creates [belief], the will also chooses it, for it will choose the two elements associated with the verse “And you shall choose life” (Deut. 30:19), namely, the pleasure of faith and the joy of service.

We are not rewarded for faith itself but for the delight we take in it and our industriousness in pursuing its truth. This also reveals the special importance of Passover and the centrality of the exodus to Jewish experience. While Shavuot commemorates the revelation at Sinai, which was the origin of an enduring faith, Passover reenacts the joy the Israelites felt after the exodus. Passover takes us back to the thrill of the first stirrings of our love of God and to the joy we therefore feel in the observance of his commandments.

Moving fluidly from reasoned argument to biblical and rabbinic sources to the arrangement of the siddur to support his view, Crescas drives home just how central the redemption of the children of Israel from enslavement in Egypt is to Judaism. Not only is the exodus mentioned repeatedly in the Torah, but all the major festivals commemorate it, as does the Kiddush recited on Shabbat and on festivals.

Crescas goes on to observe that, as the Rabbis constructed the morning prayers, they placed the Ahavah Rabah prayer, which celebrates God’s “great love” for the Jewish people as evidenced in his giving them the Torah, before the blessing “who redeemed Israel,” which commemorates the exodus—even though the exodus preceded the revelation at Sinai. One reason for their doing so is that the exodus did not attain its full redemptive significance until the people’s faith in God was decisively affirmed at Sinai. But a second reason is that it is the memory of the redemption that arouses the attachment required for a properly devotional recitation of the Amida. And this attachment is always associated with the pleasure, joy, and delight that attends serving God. Indeed, one of the things for which the Sages were praised was the joy they took in serving God. Recalling a passage in the Talmud (Berakhot 9b), Crescas recounts:

A certain rabbi was praised for being a great man who rejoiced in mitzvot. Of this rabbi, it was said that whenever he performed a mitzvah, the smile on his lips did not depart all day.

For Crescas, not all miracles compel belief, and even those that cannot be doubted—those associated with the exodus—compelled unwavering faith only when they were confirmed by the revelation at Sinai. Yet if faith is based on proof and is not on an act of the will, there can be no reward for the faith itself. Reward can only be for what is freely chosen: the feeling of pleasure in one’s faith, the joy taken in serving God and being a member of his chosen community, and the love that accompanies the recognition of God’s constant and abiding care for his people.

Suggested Reading

The Angel and the Covenant

Hurwitz’s ideal Jew is the rabbinic scholar who is also knowledgeable about, and open to, modern science.

Thoroughly Modern Maimonides?

Three recent books elucidate what, if anything, Maimonides has to say to us today.

The Rabbi Goes to Court

A new graphic novel of the Barcelona Disputation brings a famous medieval debate to life.

Is Repentance Possible?

And should we add a confession on Yom Kippur “for the sin of opening browser windows of distraction”? On Aristotle’s akrasia and Maimonides’s teshuvah.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In