Forging an Identity

In a 1949 letter to an old family acquaintance in Istanbul, a man called Mauricio Fresco described his latest book project, a work titled Forge Your Own Passport, in which he sought to “prove the stupidity of passports, visas, nationalities, races, etc.” It was an odd project, particularly for a man who had spent eighteen years in the Mexican diplomatic corps, stationed in places as far afield as Shanghai, Bordeaux, Lisbon, and Nazi-occupied Paris. But it was precisely these experiences advocating for Mexican interests at a time when the country’s immigration policies favored certain “desirable” races and nationalities (categories often as fluid as the ink they were written with) that led Fresco to his disillusioned conclusions about passports. Well, those experiences and the fact that Fresco himself had tampered with his own birth certificate, claiming to have been born in Mérida, Yucatán, despite the fact that he had actually spent the first seventeen years of his life in Constantinople, the son of a prominent Ladino newspaper magnate.

So how did a young Sephardi polyglot from Constantinople transform himself into such an exemplary Mexican that newspapers hailed him as “‘more Mexican than a nopal,’” the prickly pear featured on the country’s flag?

In part, by leveraging the very same Jewish connections he sought publicly to hide, writes Devi Mays, assistant professor of Judaic studies at the University of Michigan, in Forging Ties, Forging Passports: Migration and the Modern Sephardi Diaspora. It was in fact a letter of recommendation from Alberto Misrachi, a prominent Sephardic art dealer in Mexico City (obtained via a plea to “Jacques Benuzillo, one of the founders of the Sephardi benevolent association La Fraternidad”), that helped Fresco secure his first diplomatic post. In this way, Fresco was not unlike “countless other coreligionists from Ottoman lands,” Mays writes. He “achieved success, but only through his willingness to live on a knife’s edge, calling in favors and expecting officials to turn a blind eye.”

Forging Ties, Forging Passports is a collection of such lives: stories of savvy individuals crisscrossing the Atlantic—and sometimes the Pacific—during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries in search of wealth, marriage, asylum, fame, or all of the above; people who lived, in May’s brainy, often jargon-filled, prose, “in a state of hypermobility—sustained, long-term, nonlinear migrations lacking a clear teleology.” Mays’s book focuses specifically on the lives of Ottoman Sephardi Jews who immigrated to the Americas—and especially to Mexico—in part because she sees such migrants, who often maintained close economic, familial, and social relationships with Sephardim elsewhere, as a challenge to “the physical borders of the state and the conceptual boundaries of the nation.”

This might sound like academic jargon, but Mays has delved into Turkish, French, Spanish, and English archives across the globe (some of no-longer-existing states, such as the Ottoman Empire) to tell the stories of individuals for whom external designators of identity simply didn’t make sense:

How accurately did categories of nationality, citizenship, or even religion fit a woman like Rebecca Mitrani, born in 1881 in Kirkkilise, then a part of the Ottoman Empire, but who claimed on entry paperwork into Mexico in 1930 that Kirkkilise was part of Greece, not Turkey? Prior to moving to Mexico, she had lived in Cuba, where she gave birth to several children who migrated to Mexico with her. And though she signed her name in soletreo, the Sephardi cursive script, she declared that her religion was Greek Orthodox. From these sources, should we surmise that Mitrani felt Greek? Or Cuban? Or Greek Orthodox? Or Jewish?

Perhaps, Mitrani—like many others—simply wrote down the identifiers that would most likely help her gain admittance to Mexico, which at that time prohibited the entry of Turkish nationals and looked unfavorably on Jews. But if so, writes Mays, then doesn’t the paperwork tell us “far more about how clearly she grasped the stakes of her appearing to fit into certain categories over others in her attempt to relocate than it does about how she conceived of herself?”

The ever-shifting political regimes brought about by the First World War affected not only the livelihood and internal connectivity of the Ottoman Sephardi diaspora—located as it was amid a crumbling empire—but also their ability to move with the coming of the “Passport Age, in which passports, visas, and other forms of documentation of identity and travel became ubiquitous and often the sole basis upon which legal movement was decided.” The migrants mentioned in this book—Mauricio Fresco and Rebecca Mitrani among them—showed tremendous dexterity in navigating this paperwork. The Sephardim who made their way to Mexico in the early twentieth century often “played” the multiple legal systems traversed, sometimes feigning to be Greek Orthodox, Italian, or French.

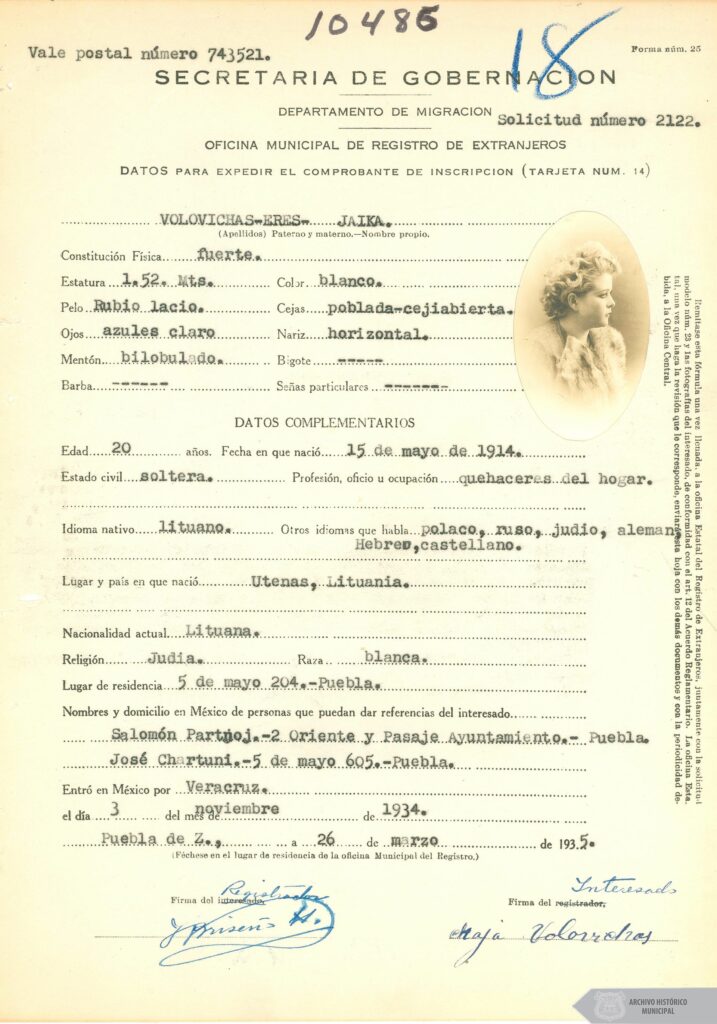

Registration sheet for the entry of Jewish immigrants to Puebla – File 9321, 3 November 1934. (Municipal Archive of the city of Puebla.)

Some left their hometowns to avoid being drafted into the First World War; others sought economic opportunities; still others, especially French- and Ladino-speaking Jews, found themselves excluded from emerging conceptions of Turkish identity. “For many,” Mays writes, “an uncertain future in foreign lands was preferable to an uncertain future in Ottoman territories, fast becoming foreign to its own inhabitants.”

But as uncertain as the future was for potential émigrés, many did have some idea of what life was like across the ocean, thanks to strong transnational Sephardi networks and well-connected media. “By 1920,” Mays writes, “newspapers published in Ladino in New York boasted of agents as far afield as Seattle, Havana, Mexico City, Rio de Janeiro, and Skopje [North Macedonia] and readers throughout the Americas, Europe, and Asia.” And the exchange went the other way too. Ladino journals in Izmir and Istanbul regularly published pieces drawn from Jewish and non-Jewish publications in Europe and the Americas. “In time,” writes Mays, “it could be boasted that subscribers were able to read Ladino newspapers on five continents.”

And these transnational networks were not limited to formal media institutions. Social networks, such as extended family members and rabbis, helped people search for lost relatives or obtain character assessment of potential spouses met abroad. There were also more punitive uses, writes Mays, with migrants sometimes threatening to report people to family members in their places of origin should they misbehave. Ladino periodicals also “reported on, shamed, and sought to track down migrant men who had abandoned wives, dodged the draft, or committed murder.” These tightly knit social networks help explain why Sephardi immigrants from the Ottoman Empire often preferred migration to Mexico over the United States. Moreover, in the US, Sephardi immigrants were often outnumbered by their Ashkenazi counterparts, and many occupied the “lower rungs of society, [while] those who went to Mexico, by virtue of their linguistic proficiency and their understanding of social and cultural norms, had greater opportunity for upward mobility.” In one of the more charming anecdotes of the book, Mays underlines just how much difference this linguistic familiarity made for new immigrants:

My strongest impression was during my first nights [in Mexico] when I lay down and heard noise in the street of the people speaking Spanish, I would say ‘But this city is full of Jews!’ recounted one Sephardi migrant, noting how Spanish made Mexico seem familiar to newly arrived Sephardi immigrants for whom a Hispanic language indicated Jewish origins.

But while linguistic similarities meant Sephardi migrants to the Americas often adapted quickly to their new home, it doesn’t mean that they sought to blend in. In fact, many savvy Sephardi Jews capitalized on what Mays calls “ambiguous foreignness” and took advantage of the French education received through the Alliance Israélite Universelle to project a sophisticated European persona. The Sofia-born Sálomon Levy, for example, affected a French identity to sell his wares to his Mexican clients, who “were desirous of the social capital that French fashions conveyed”; Levy even spun tales of his life in Paris, though he’d never been to the city. (Though sometimes useful, this connection with whiteness could also be dangerous, since Middle Eastern migrants, by virtue of their foreignness and blue eyes, where often conflated with Spanish, European, and American colonizers and accused of exploiting the indigenous working class.)

“Dissimulation, self-fashioning, and improvisation had long been critical elements in the experience of individuals who lived their lives on a global stage,” writes Mays in her book’s introduction. But this was especially true for members of the Ottoman Sephardi diaspora in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, for whom surviving—and eventually thriving—depended on their ability to make and remake themselves, often with the help of a wide-ranging network of fellow Sephardim across the globe. Forging Ties, Forging Passports makes these points, and makes them well, but the real attraction of this book is less in its historical thesis (repeated frequently, at times with a heavy hand) and more the evidence Mays has gathered to support it—the tremendous tales of individual and communal perseverance, canniness, and luck that she pieces together from over a dozen archives in seven different countries.

Indeed, many of the stories are so dramatic that I frequently found myself wishing I had first encountered them in a form more naturally suited to the material—a historical novel, maybe, like John Dos Passos’s U.S.A. trilogy, which could convey not just the fact of displacement but its experience. Mays gives a bird’s-eye view of her many subjects’ life trajectories across multiple geographies and with the vantage point of hindsight. One might occasionally think that each character in the text had a similar view of the entire panorama. But, of course, immigrants like those Mays writes about never knew how their lives—and gambles—would turn out.

Suggested Reading

Crazy Rich Sephardim

For a time, Shanghai soared along with these unusual Ottoman Jewish émigrés, the Sassoons and the Kadoories.

Passport Sepharad

The recent offers of citizenship by Spain and Portugal tap into a long, rich, and complicated Sephardi history of dubious passports, desperate backup plans, and extraterritorial dreams.

The Sephardic Mystique

In the late 18th century, an ardor for ancient Greek art and literature swept through German letters. German Jews were not immune, yet during the same period, they also devoted themselves to recovering the linguistic, artistic, and literary heritage of medieval Sephardic Jewry.

No Tips

Yale's Jewish Lives Series finds an unlikely subject: Leon Trotsky.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In