Between Frankfurt and Jerusalem: Scholem, Adorno, and the Fate of the Sacred

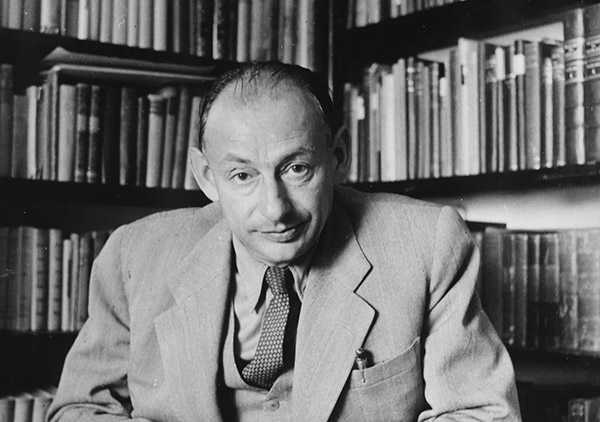

They first met in a Frankfurt hospital in 1923. Theodor Wiesengrund Adorno, nineteen years old, said Gershom Scholem, then twenty-six, gave “the impression of a Bedouin prince.” Adorno remembered that Scholem had appeared in a bathrobe, though he conceded that the memory “might involve much retrospective fantasy.” Over the next fifteen years,Scholem and Adorno remained wary of one another. When Adorno’s first book was published ten years later, Scholem wrote to their mutual friend Walter Benjamin that it “combines a sublime plagiarism of your thought with an uncommon chutzpah.”

The tone shifted when they next met in 1938, at Benjamin’s urging, at the Manhattan home of Paul and Hannah Tillich. Scholem was in town to give the lectures that became his pathbreaking book Major Trends in Jewish Mysticism. Adorno, having been dismissed as “non-Aryan” from his university post, had been forced to flee Nazi Germany four years earlier. Each reported the encounter to Benjamin. “I like him immensely,” Scholem reported, “and we found quite a lot to say to one another.” “Not exactly the best atmosphere in which to be introduced to the Zohar,” Adorno wrote to Benjamin.

Especially since Frau Tillich’s relationship to the Kabbala seems to resemble that of a terrified teenager . . . to pornography. The antinomian Maggid [Scholem] was extremely reserved towards me at first, and clearly regarded me as some sort of dangerous arch-seducer. . . . Nevertheless, I somehow succeeded in breaking the spell and he began to show some kind of trust in me, something which I think will continue to grow.

Guided by that trust, Scholem and Adorno began writing to one another. Their thirty-year correspondence—first issued in 2015 by the German publishing house Suhrkamp and now appearing in English for the first time—is illuminated by the aftermath of catastrophe. Besides registering the irrevocable ruptures of their time, it brings to light dimensions of each writer not apparent in scrutinizing them separately.

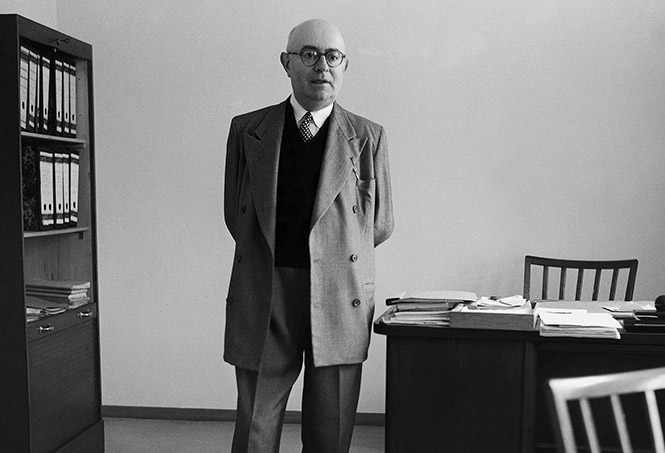

Adorno and Scholem, one of Adorno’s closest students would later say, were as different as “a sea creature and a land animal.” “Teddie” Adorno, as he signed himself, returned four years after the Shoah to his native Germany (at first part-time and then permanently), where he established himself as one of the country’s leading philosophers, social critics, and musicologists. The Shoah, Adorno taught, had imposed a “new categorical imperative”: we must arrange our actions such that “Auschwitz would not repeat itself.” An atheist Marxist (though a staunch critic of the Soviet Union who found Marx’s interpretation of capitalism outmoded), he cofounded the so-called Frankfurt School of “critical theory.” Unlike Scholem, his sense of Jewishness was profoundly conflicted. (His father was Jewish, his mother Italian Catholic, though his ambivalence was more than a matter of parentage.)

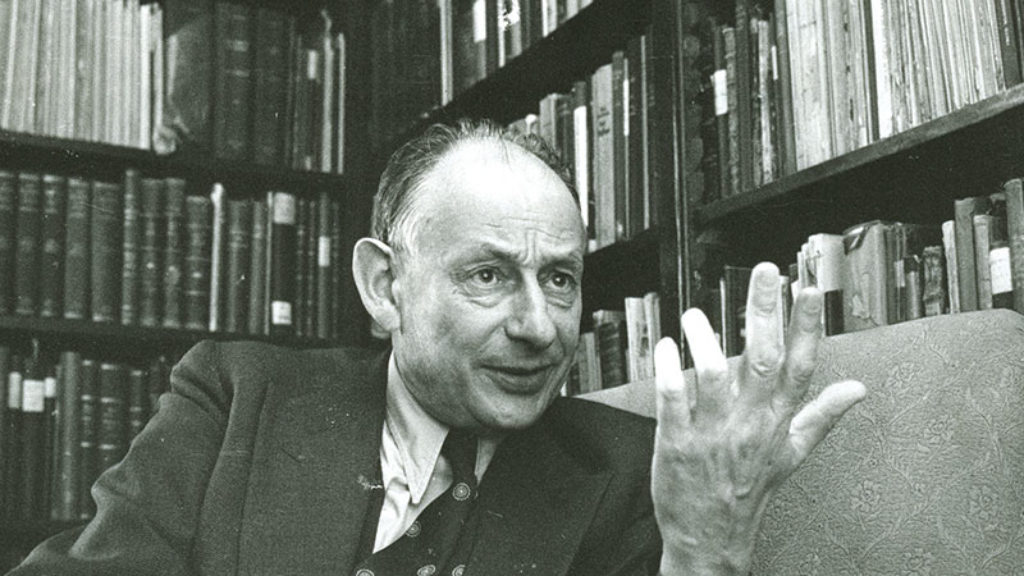

Scholem, an early and ardent Zionist, left Germany in 1923 for Jerusalem, where as a professor at the Hebrew University, he would embark on a lifelong wresting of Jewish mysticism from the shadows of esotericism into the light of scholarship, giving a rational reconstruction of the irrational forces in Jewish history. Scholem describes himself to Adorno as an “avowed non-Marxist” and “anything but an atheist.” He was allergic to “critical theory,” a term he insisted was “designed simply as a code word and esoteric synonym for Marxism, nothing more. Everything else is a swindle.” After the Shoah, he refused to speak publicly in Germany until 1957, when he came at Adorno’s invitation. Nor did he allow his books to be printed by German publishers until the 1960s. Though he continued to write some of his most important work in German (including Major Trends in Jewish Mysticism and Origins of the Kabbalah), Scholem addressed his writings—which he knew to belong to Jewish literature—to Jewish audiences; Adorno addressed his to German readers.

Yet for all their divergences, they absorbed and esteemed each other’s work. In his letters, Scholem reports taking Adorno’s The Jargon of Authenticity (a polemic against Martin Heidegger) with him on vacation in Tiberias. He offers discerning comments on Adorno’s masterwork, Negative Dialectics, a critique of the idealist philosophies of Kant and Hegel. Minima Moralia, Adorno’s collection of aphorisms, strikes him as “one of the most remarkable documents of negative theology.” Although he protests in one letter that “I unfortunately understand nothing of music,” Scholem responds with insight to Adorno’s reflections on contemporary sacred music and thanks Adorno for dedicating his study of Arnold Schoenberg’s opera Moses und Aron to him.

If Adorno comes across here as a kind of secular priestly Aaron, Scholem becomes Adorno’s Urim ve-Tumim in all matters Jewish. Having read Scholem’s Major Trends “over and over,” Adorno reports being “powerfully moved by the chapter on Lurianic mysticism” and adopts an idiosyncratic interpretation of the Lurianic image of shevirat ha-kelim (the bursting of the vessels), a shattering that accompanied the creation of the world. Mending this brokenness, Adorno suggests, depends on learning to see the world, “with its rifts and crevices, as indigent and distorted as it will appear one day in the messianic light.”

Sometimes the esteem was beset by mutual incomprehension and obscured by the inscrutability of each other’s texts. Scholem confesses to “having admired you much more than I’ve understood you.” Adorno writes to Scholem: “These days, I am deeply engaged with your ‘Unhistorical Aphorisms’ on Kabbalah. . . . It’s an inhumanly difficult text, and, although I am indeed accustomed to a lot, I would not presume to have understood it completely.” Scholem replies with characteristic wit:

By agreeing to have the unhistorical aphorisms on Kabbalah printed, I have decisively sinned. . . . Now you want a commentary—what are you thinking? Such things existed only in the olden days, when authors wrote their own commentaries, and, if they were clever, these said the opposite of what was said in the texts.

Later, Scholem sends Adorno his translation of a Zohar text. Adorno answers: “its very indecipherability is a part of the pleasure that it gave me.” And yet he does understand something:

I had imagined the Zohar to be the most inward and hermetic product of the Jewish spirit, as it were. But I now find that, in its very foreignness, it is most enigmatically intertwined with Western thought. If the Zohar indeed represents the Jewish document in an eminent sense, then, at any rate, it does so in the mediated sense in which the Galut constitutes the Jewish fate.

In reply, Scholem agrees: “What is uncanny and attractive about these texts lies precisely in the extent to which the most original products of Jewish thought are of an assimilatory nature.”

Scholem and Adorno found kinship and common language—or what Adorno calls the “shared substance [that] has crystallized between us over the years”—in three disdains and a love.

They shared a disdain, first, for Hannah Arendt, the political theorist who fled Germany in 1933 and authored influential books including The Origins of Totalitarianism, The Human Condition, and Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil. In rather misogynistic letters to Scholem, Adorno calls her “an old washer-woman” and chastises her “boundless ambition and her intellectual neophytism.” Scholem, in turn, refers to Arendt’s “addiction to originality,” her “method of arrogant and brash insolence,” and “a bitter ressentiment, which shines forth in everything she’s written on Zionism and Zionists.” In a long and candid letter of January 1946, Scholem had rebuked Arendt for her essay “Zionism Reconsidered.” More than fifteen years later, they famously broke relations after his furious response to her book on the Eichmann trial.

The second lightning rod of their disdain was Martin Buber, Vienna-born author of I and Thou. Adorno tells Scholem that Buber’s brand of existentialist philosophy “definitely belongs to the context of the darkest German ideology.” Scholem sends Adorno his devastating critique from Commentary magazineof Buber’s interpretation of Hasidism and calls Buber “a helpless windbag.” Returning from Buber’s funeral in 1965, Scholem comments to Adorno on Buber’s “enormous success with the Germans, as well as his complete failure with the Jews.”

Finally, Adorno and Scholem shared a contempt for the complacencies of “German-Jewish dialogue.” Scholem felt that those of his predecessors dedicated to such a dialogue—including the historians Leopold Zunz and Heinrich Graetz—had labored under a dangerous illusion. Adorno concurred:

Given what happened, even the words “German–Jewish conversation” are enough to make one sick. It’s the simple truth that such a conversation never took place. . . . It’s a truly abysmal irony that the German interest in Judaism qua Judaism, as opposed to individual Jewish figures, has set in only now that there are no more Jews there.

Yet stronger than any disdain was their shared love for the German Jewish literary critic and philosopher Walter Benjamin. Even more so than the better-known correspondence between Scholem and Arendt (reviewed in these pages by Steven Aschheim, “Between New York and Jerusalem,” Winter 2011), the Adorno-Scholem correspondence orbits that love. All but four of the more than two hundred letters the two men exchanged came after Benjamin’s suicide in 1940 while on the run from the Nazis.

Much as Scholem rescued the musings of obscure mystics of Tzfat and Provence, Scholem and Adorno found common cause in gathering their friend’s dispersed manuscripts and letters, acting as Benjamin’s self-appointed literary executors and lobbyists, salvaging his legacy from oblivion, and protecting it, as Adorno writes to Scholem, “from posthumous defamations.” In a sense, they brought the literary figure of Benjamin into full-fledged being. Not for nothing did Gershom Scholem sign one of his letters to Adorno “G . . . olem.” After editing a two-volume collection of Benjamin’s writings (1955), Adorno collaborated with Scholem on gathering, editing, and publishing Benjamin’s letters (1966), many of which Scholem guarded—and venerated—in his home in Jerusalem. (Scholem’s wife Fania said that the only person Scholem ever truly loved was Walter Benjamin.)

Scholem’s work with Adorno on Benjamin’s writings greatly enhanced Scholem’s profile in Germany. This was by design. “Everything that Scholem wrote about Benjamin,” Noam Zadoff notes in his biography of Scholem, “was in German and was published in Germany and, with a single exception, none of what Scholem wrote about Benjamin was translated into Hebrew during his lifetime.”

“To do justice to the figure of Kafka in its purity and its peculiar beauty,” Walter Benjamin once said of the Prague writer, “one must never lose sight of one thing: it is the purity and beauty of a failure.” Adorno and Scholem saw in Benjamin, too, a figure of beautiful failure. They shared an attempt to redeem that failure, or at least to find meaning in it.

Scholem at first registered “considerable surprise at Adorno’s appreciation of the continuing theological element in Benjamin.” As if sensing this, Adorno assured Scholem that he has no doubt Benjamin “assumed Jewish mystical teachings as binding for his own work.” And not Benjamin alone. “A whole group of Jews from this generation,” Adorno writes, “Kraus, Kafka, Schoenberg, perhaps also Freud, and, above all, Mahler—harbored traces of this mystical tradition (God knows where they got it from), as well as its radical metamorphosis through secularization.”

That last word threads through the conversation. Together with their love of Walter Benjamin, and inextricable from it, Adorno and Scholem shared a preoccupation with the fate of the sacred in secular society, with what Adorno calls in a letter to Scholem its “unflinching migration into the profane,” and with the questions raised by that migration. Can Judaism still flourish under conditions of secular modernity? How urgently do secular societies still need living religious traditions? How can we negotiate the startling swerves between religious past and secularized present?

In the twilight of his life, Adorno was dogged by more mundane concerns. Critics on the left charged him with manipulating Benjamin’s legacy—he complained to Scholem of a “smear campaign.” Student revolutionaries regarded him as a closet conservative. Years earlier, Scholem had noted to Adorno that “many of your deepest insights are bound up with your anarchist élan and anarchist tendency.” But Adorno did not find the new anarchists of the late 1960s amusing. In April 1969, three women activists leapt toward his podium and bared their breasts, disrupting his lecture. Invoking the term in Genesis for primordial chaos, Adorno describes the pervading atmosphere to Scholem as “tohu va’vohu.” “The pseudo-revolution is spinning out of control,” he writes, and “weighed so heavily on me that I could not muster any of that halcyon cheerfulness that Nietzsche recommends for ambitious authors. The song ‘Hang the Professors,’ which I had to listen to repeatedly, is not exactly conducive to such cheerfulness.”

Six years earlier, Scholem, having committed to give a talk elsewhere, had to decline the invitation to his fellow heretic’s sixtieth birthday party in Germany. “Despite what might be expected of a man in my profession,” he tells Adorno, “I cannot magically appear on the roof of the Frankfurt Society for Commerce and Trade.” The maggid of Jerusalem would instead rush to Frankfurt for his friend’s funeral, following Adorno’s sudden death of a heart attack in August 1969, just shy of his sixty-sixth birthday. In his last letter to Scholem, Adorno was hatching plans to visit Israel for the first time.

Theodor Adorno said of Walter Benjamin’s correspondence: “The level and quality of letters is always also determined by its addressee.” The quality of the Adorno-Scholem correspondence, intelligently introduced by Asaf Angermann and elegantly translated by Sebastian Truskolaski and Paula Schwebel (and with assistance from Stephanie Graf), is correspondingly high. It’s well worth lifting our eyes to see it.

Suggested Reading

A Dissonant Moses in Berlin and Paris

Schoenberg’s challenging opera is re-staged in 21st-century Europe.

Remembering the Scholems

New books about Gershom Scholem and his brother Werner evoke memories of 28 Abarbanel Street in Jerusalem.

The Book of Radiance

Daniel Matt’s massive new English edition of the Zohar is not only a great translation, it is also one of the great commentaries on the classic work of Jewish mysticism. Insofar as it is possible, Matt has brought the unfathomable, mysterious, and poetic depths of this “book of radiance” to the English reader.

The Secret Metaphysician

While a new crop of biographies about Gershom Scholem all, in one way or another, seek to account for the great man's fascination, they are themselves evidence of Scholem’s ongoing allure.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In