Inside-Out

One of the most popular Jewish stories that circulated in the late Second Temple period begins with representatives of the Assyrian king Nebuchadnezzar ordering Judeans to support their military campaign. When the Judeans refuse, the empire sends a general named Holofernes to punish them—first through siege and starvation and then by attack. As the town of Bethulia’s panicked elders declare a public fast, a woman named Judith concocts a bolder plan. She tells Assyrian guards camped at the edge of town that she is defecting to their side and is led to the tent of Holofernes, whom she seduces over the next few days. One night, after the general has passed out in bed following an evening of debauchery, she stands at his bedside, utters a prayer to the God of Israel, and chops off his head.

The Jews who first read this story knew that it could never have happened. The Assyrian empire never had a king named Nebuchadnezzar, which is the name of the Babylonian king responsible for the Jerusalem Temple’s destruction. Nor was a Babylonian or Assyrian king likely to have had a general with a Greek name like Holofernes. There is also no evidence that there ever was a Judean town named Bethulia (a made-up word that means Virgintown).

The writer of Judith’s story may have fabricated key details, but he was far from sloppy. The book’s narrative features are lifted from the biblical book of Judges, which recalls how the prophetess Deborah and the Kenite woman Jael defeated the Canaanite general Sisera. The writer transformed this story into a contemporary tale that conveyed the message that God will always protect the people of Israel from their enemies. Why, then, was this tale not preserved in the Jewish Bible?

On the face of it, the answer to this question is straightforward. By the end of the Second Temple period, the books included in the Torah and the Prophets (Nevi’im) had long been agreed upon. Judith was written after these two collections were closed and after most texts that were to be included in the Bible’s third collection, known as the Writings (Ketuvim), were composed. And because it circulated in Greek as well as in Hebrew, Judith was unlikely to make the cut.

And yet, perhaps some Jews who lived during the late Second Temple period did view Judith as scriptural, since the concept of holy scriptures had not yet crystallized into a fixed corpus. This flexible attitude, particularly as it applied to the category of Ketuvim, continued into the Common Era. The Mishnah, written around 200 CE, records debates about the scriptural standing of controversial works such as Ecclesiastes and the Song of Songs. It was only at this time, or shortly thereafter, that Jews and Christians began compiling lists of their holy scriptures, which Christians called “canons” (named so after the Greek kanon, a reed commonly used as a measuring stick).

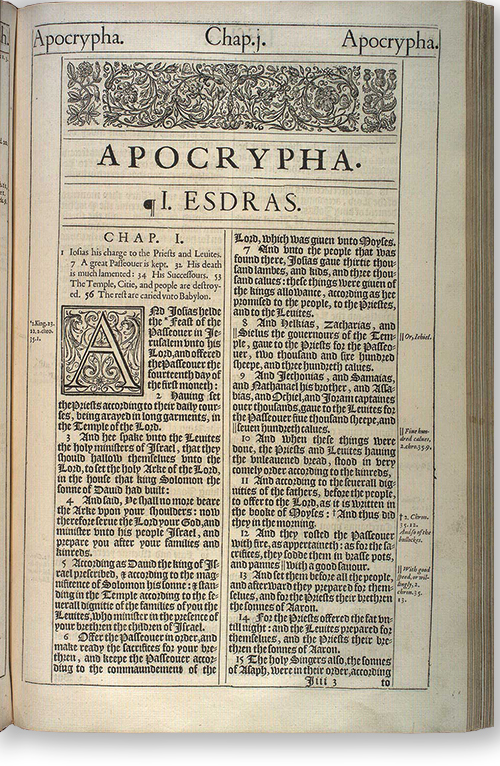

Christians in late antiquity read Judith as part of an unstable collection that came to be known as the Apocrypha, meaning “hidden things.” Some Christian communities viewed these books as semicanonical (“deuterocanonical”) or even as fully canonical. The rabbis, by contrast, made occasional references to forbidden “external books” (sefarim hitzonim). But they also sometimes quoted the uncanonized wisdom text Ben Sira, and they never established a list of these forbidden books. Over time, the Hebrew Bible became established as a closed canon that told Jews who they were, and the Apocrypha took on the role of telling Jews who they weren’t.

Today, traditional Jews tend to regard the Apocrypha as an enigmatic heresy, a threat to the preservation of an uncorrupted transmission of Torah from Sinai. For these Jews, the Apocrypha is a religiously insignificant novelty, an obscure set of curious historical off-ramps bypassed by authentic Judaism.

Such negative attitudes toward the Apocryphal books throw the outsized influence of a few of their heroes, such as Judah Maccabee and Judith, who have captured Jewish imaginations for two millennia, into surprising relief. These heroes, and their stories, slip both above and below the surface of Jewish literature, appearing in unexpected places, only to disappear again. But as a literary collection, the Apocrypha has yet to be reclaimed as a set of Jewish texts.

In Introduction to the Apocrypha: Jewish Books in Christian Bibles, Lawrence M. Wills makes two important claims. The first is that the Jewish texts that comprise the Apocrypha should not be read through the lens of the Christian Bibles that preserved them. The second is that they should also not be read through the lens of later rabbinic texts that ignored them. The Apocrypha, Wills suggests, must be read on its own terms. Once this is done, however, something unexpected happens: it ceases to exist as a distinct category.

The central argument driving Wills’s study is that the Apocryphal books share common themes but form an unstable category. Studying these texts as an internally cohesive collection inevitably shapes our understanding of them and of the religious and social worlds that stood behind them. The best way to read these books, Wills implies, is to free them from the constraints of “the Apocrypha.”

Such an approach is eminently reasonable but religiously dangerous. If categorical dissolution makes sense for the Apocrypha, could it also be best for the Hebrew Bible? The three sections of the Tanakh are, after all, also collections of works that were composed in different times and places. What happens if we release the Hebrew Bible and let its words flow into apocryphal tributaries?

The first thing that happens is that the similarities between the Apocrypha and the late books of the Hebrew Bible become impossible to ignore. Both collections transmit older scriptural traditions by developing them into new ones. And both borrow language from the Torah and the Prophets to carry on the scriptural tradition. In the Apocryphal book of Baruch, for instance, the Judean community of Babylonia bemoans the shame of exile:

And you shall say: The Lord our God is in the right, but there is open shame on us today, on the people of Judah, on the inhabitants of Jerusalem, and on our kings, our rulers, our priests, our prophets, and our ancestors, because we have sinned before the Lord. . . .

The Lord our God is in the right, but there is open shame on us and our ancestors this very day. (Baruch 1:15–17, 2:6)

The association of diaspora and shame runs through biblical literature, but the author of Baruch did more than borrow a biblical idea: he borrowed biblical language. The biblical book of Daniel cites a prayer uttered by the prophet after he receives a prophecy that the Judeans will be subject to the “open shame” of exile for seventy years:

Righteousness is on your side, O Lord, but open shame, as at this day, falls on us, the people of Judah, the inhabitants of Jerusalem, and all Israel, those who are near and those who are far away, in all the lands to which you have driven them, because of the treachery that they have committed against you. Open shame, O Lord, falls on us, our kings, our officials, and our ancestors, because we have sinned against you. (Daniel 9:7–9)

The similarities between these two passages are hard to miss. And because scholars date the second half of Daniel to the second century BCE, Baruch and Daniel could have been written within just a few decades of one another. Wills, moreover, suggests that the connections between these passages show evidence of a common liturgy during this period. Why, then, was Baruch excluded from the Hebrew Bible?

It is possible that the rabbis read Baruch as an unremarkable copycat of earlier texts. But it is just as possible that the premise of the question is wrong: maybe the book of Baruch was read as authoritative by some Jews, especially in its original Hebrew version. All we know is that Baruch did not make it onto rabbinic lists of scriptural books that were recorded a few hundred years after it was written.

Sometimes a work preserved in the Apocrypha appears to be more pious than its biblical parallel. Take the biblical and apocryphal versions of Esther. The book of Esther we all know introduces its heroine as the orphaned cousin of Mordechai, whom he raises as his own. The author provides no information about Esther’s personality, piety, or personal preferences. All we are told by way of introduction is that “the girl was fair and beautiful, and when her father and her mother died, Mordechai adopted her as his own daughter” (Esther 2:7).

Normally, when biblical characters lack internal depth, it is a signal to readers that they should train their focus elsewhere. But the more we look for the story of Esther’s focus, the more out of focus it becomes. The absence of religious material, theological perspective, scriptural law, and allusions to Israelite history deprive the story of context that the reader requires to understand its meaning. It has long been recognized that Esther’s salvation story lacks the most important character: the god who brings salvation. But the most egregious sin of this biblical book lies in its happy ending, when Ahasuerus and Esther walk off into the sunset as an intermarried couple.

By the second century BCE, the Hebrew book of Esther was probably widely accepted by Jews as an authoritative work associated with the popular holiday of Purim. But this version was evidently considered so problematic that bilingual Jews in Jerusalem decided to produce a new version of the story that added dramatic flourishes and pious details. Among these are two climactic prayers uttered by Mordechai and Esther that invoke God’s past interventions on behalf of the Jewish people. The story’s new version uses the Greek word for Jew or Judean, Ioudaios, more than forty times. It also clarifies that Esther abstained from eating at the king’s table, presumably because she kept kosher.

Should we treat the Greek book of Esther as a competing version of the biblical story or as a kind of proto-midrash that elaborated on the biblical story without trying to displace it? Once again, we may be asking the wrong question. The first generation of Jews who read this work were probably unconcerned with its relationship to the Hebrew Bible. This Bible, as the rabbis would later define it, did not yet exist.

This brings us back to Judith, a story that, like Esther, features a beautiful and unattached heroine who saves her Jewish community from annihilation at the hands of a foreign enemy. Unlike the biblical book of Esther, the story of Judith touches on the three major markers of Jewish identity in the ancient world: the practices of circumcision, dietary law, and the Sabbath.

It introduces the heroine as follows:

Judith remained as a widow for three years and four months at home where she set up a tent for herself on the roof of her house. She put sackcloth around her waist and dressed in widow’s clothing. She fasted all the days of her widowhood, except the day before the sabbath and the sabbath itself, the day before the new moon and the day of the new moon, and the festivals and days of rejoicing of the house of Israel. She was beautiful in appearance, and was very lovely to behold. . . . No one spoke ill of her, for she feared God with great devotion. (Judith 8:4–8)

The author of Judith may have been responding to the Hebrew version of Esther by writing a more religiously satisfying version of the same basic story. Alternatively, he may have modeled Judith not after Esther but after the similarly named Judah, the Hasmonean hero whose weaponry was not sex but sword and shield. Reading the book of Judith as a subversive retelling of Judah Maccabee’s victories makes good sense: the book was likely composed shortly after the Hasmonean victory over the Seleucid Greeks.

Wills explores both of these possibilities and also makes a compelling case for the likelihood that the author was working with histories composed by Herodotus, Ctesias, and Xenophon. These Greek histories, and other contemporaneous legends, feature warrior women like Judith who embody the qualities of self-control, bravery, and boldness of speech.

Wills treats Judith, and other apocryphal books, as a constellation of texts that give competing answers to questions about Jewish piety, belief, and practice. The author of Judith, for instance, believed that fasting was a key feature of religious piety, provided that it was not done to force God into action, while the author of Tobit preferred treating gifts to the poor as the main barometer of individual piety. The author of 1 Maccabees opposed choosing martyrdom over breaking the Sabbath, while the author of 2 Maccabees supported it.

Perhaps the biggest area of disagreement among Jewish writers at this time concerned the matter of loyalty to Jerusalem and its Temple. The author of 2 Maccabees declared that this Temple united all Jews in the Hellenistic world. The author of 3 Maccabees, however, featured Jewish heroes who insisted on the legitimacy of a permanent and thriving diaspora. Sometimes differences fall along geographical lines, with Judean texts advocating for obedience to priests and loyalty to the Temple and diasporan texts highlighting God’s universal love for all Jews, despite their distance from the Temple. But there are plenty of exceptions to this rule: the authors of 2 Maccabees and 3 Maccabees both lived in the diaspora. Moreover, some Judean texts read like Greek novellas and make little reference to the Temple or even to Jerusalem.

The Apocrypha is just the tip of the iceberg. Most of the thousands of pages produced by Jews in the Second Temple period that have survived were not included in the Apocrypha, and these undoubtedly represent just a tiny fraction of what Jews actually produced.

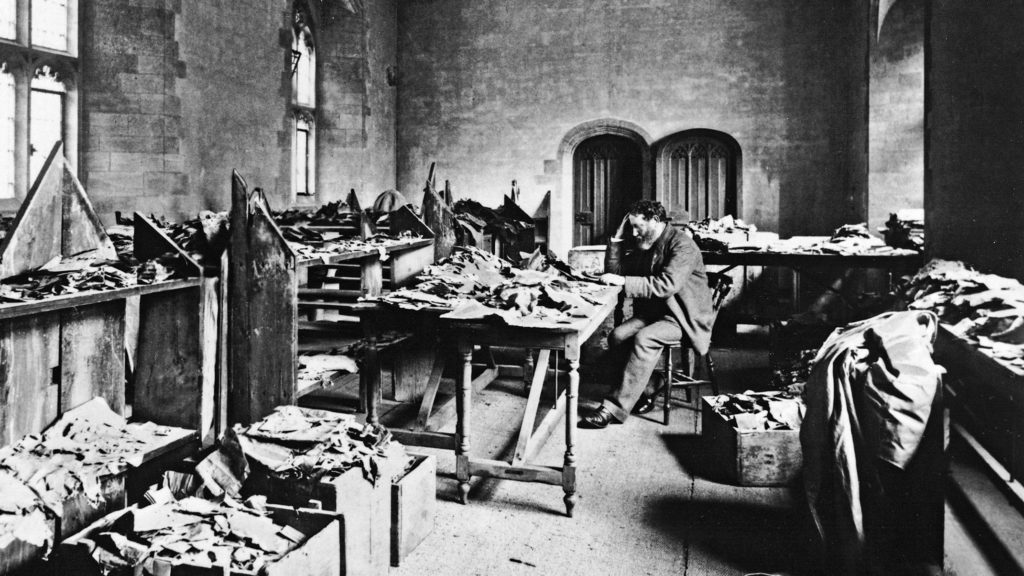

Consider the amorphous and ever-expanding set of texts known as the Pseudepigrapha. The term, which means “falsely attributed writings,” was invented by an eighteenth-century German Lutheran scholar named Johannes Fabricius, who gathered ancient manuscripts from his travels to distant monasteries and church libraries. The Pseudepigrapha includes thousands of pages from lost novellas, prayers, incantations, poems, interpretations, and histories that were mostly composed between the fourth century BCE and the fourth century CE. Aside from holding religious significance for the Christians and occasional Jews who preserved them, pseudepigraphic texts have no intrinsic relationship with one another. Many of these texts don’t look very different from the books of the Apocrypha. Some of them don’t look very different from the books of the Bible.

Wills’s book is the latest effort in the modern project to expand our understanding of ancient Jewish literature, which arguably began with Fabricius. From Fabricius through R. H. Charles, who published English translations of the Apocrypha and Pseudepigrapha in 1913, this project was a largely Protestant attempt to argue for the legitimacy of Christianity by reading Christian values into ancient Jewish works. But in the past half century, the expansion, publication, and study of the Pseudepigrapha has become linked to the effort to read ancient Jewish texts on their own terms.

The ever-growing editions of Pseudepigrapha have helped to destabilize the notion that Jewish books produced in the Hellenistic period held either a canonical or heretical status. But it was the 2020 publication of The Jewish Annotated Apocrypha, which Wills edited with Jonathan Klawans, that brought this idea to a mainstream audience. In the present work, Wills returns to the idea that, rather than thinking of ancient Jewish texts as canonical or noncanonical to all, modern readers should treat both biblical and apocryphal texts as having once been authoritative to many.

Wills also elegantly traces the afterlives of figures such as Esther, Judith, and Susanna in Christian artistic and literary imagination. But he does not explore the Jewish reception of apocryphal stories beyond quoting a few rabbinic texts. In other words, he does not go far to seek what the rabbis sought to hide. As Wills may well realize, this decision underlines his point that these stories have yet to be reclaimed as Jewish.

The most interesting implications of Introduction to the Apocrypha are theological. As Wills puts it, “If different religious traditions grant authority to a Bible as a sort of constitution, the extra texts then indicate a shadow zone where the constitution is negotiated or expanded.” This theological cliff-hanger raises the stakes of Wills’s historical argument. Does the dissolution of boundaries between holy and profane texts dissolve the boundaries that keep the people of Israel separate from the rest of humanity? When the collection of Jewish scriptures dissolves, what is left that makes the Jewish people special?

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

Hidden Faces and Dark Corners: Megillat Esther and Measure for Measure

What happens when the hidden is revealed? Reading Megillat Esther alongside one of Shakespeare’s “problem plays” shows that question to be at the heart of Purim’s paradox.

Buried Treasure

Hundreds of thousands of Jewish manuscripts were redeemed from Egypt.

Inside or Outside?

After the discoveries of the Cairo Geniza and the Dead Sea Scrolls, scholars of Judaism slowly began to reconstruct the 400-year period separating the latest parts of the Hebrew Bible from the earliest rabbinic compilations.

The Apocryphal Psalms of David 1:15–20

In 1902 Abraham Harkavy published two previously unknown psalms and parts of two others from a manuscript in the Cairo Geniza. They may date back to the Second Temple.

gershon hepner

Malka Simkovich writes, in her fascinating article on the Apocrypha, “Inside-Out”:

All we know is that Baruch did not make it onto rabbinic lists of scriptural books that were recorded a few hundred years after it was written.

It is interesting to recall the Jonathan Sarna in a artice inLehrhaus, 1/5/17 (“Praying for Governments We Dislike?”), draws our attention to a footnote in a Russian siddur from the late Tsarist era. This footnote cites Baruch 1:11 as a justification for reciting the traditional Ha-noten Teshu’ah prayer for Nicholas, Alexandra, queen mother Maria and crown prince Alexei, notorious antisemites whom the prayer exalts in the loftiest of tones. Sarna makes a brilliant apologia for the siddur’s use of the apocryphal text without applying my I hope apposite use of alliteration to justify citation of the apocryphal text

A microscopic footnote, however, explains that, according Jews are enjoined to pray even for the life of King Nebuchadnezzar. Through this tacit aside—so oblique that it eluded the watchful censor’s pen—the siddur covertly linked the Tsar to the most despised of diaspora monarchs, even as it overtly celebrated his name in large black letters.

maieutic

Does Judaism really aim to create "boundaries that keep the people of Israel separate from the rest of humanity"?