The Art of the Dealer

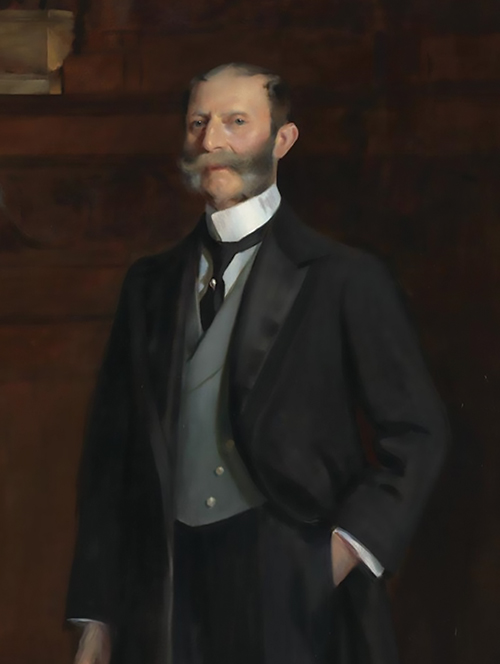

When he visited the Louvre for the first time, in 1875, Nathan Wildenstein did so not for pleasure but for business. He sold textiles, and a client in his small Champagne town had asked for his help in selling some paintings. Utterly ignorant about art, he needed to get up to speed as quickly as possible, so for ten days, he settled into the great museum and somehow gave himself an education. The commission Wildenstein received when he sold the art launched him on a new hugely successful career. Thirty years later, with provincial life far behind him, he was living in Paris in the Hôtel Wildenstein, which, Charles Dellheim writes, “occupied the width of an entire city block (with its rear facing out onto Faubourg St. Honoré) and contained more than enough room for exhibition space and a family apartment.”

In Belonging and Betrayal, Dellheim shows that the shift of many Jewish businessmen from trade in cloth, grain, or cattle to works of art was a natural and even logical progression. Although only a relative handful of Jews ever entered the field, art dealing became enough of a Jewish commercial niche to become emblematic of the link between art and commerce. What was different about art was that it not only had high margins; it also counteracted the stereotype of Jews as grasping materialists. If the poet Heinrich Heine famously quipped that a baptismal certificate was his ticket to European civilization, then a certificate of provenance for a work by an old master attested to its owner’s connoisseurship—with the advantage that he could remain a Jew and become a civilized European. No wonder the Nazis sought to separate the Jews from their art as a crucial step in de-emancipating them.

The circumstances triggering the shift from ordinary commodities to art often appear coincidental, but Dellheim shows how it made sense:

Appraising loans and jewelry and purveying textiles and furs had served to cultivate in these new art dealers a feeling for authenticity, a sense of style, and a capacity for close observation, all of which proved invaluable to prospective connoisseurs. The art market was, among other things, a fashion business, resembling other industries in which Jews made a mark: retail, clothing, and, eventually, movies.

Here we have the starting point for a plausible theory of Jews as leading mediators of modern culture.

Belonging and Betrayal offers a model for how to intelligently explain the causes and significance of Jewish overrepresentation in many areas. Dellheim recognizes that Jewish immersion in cultural enterprises was often both aesthetic and economic.

Since the Middle Ages, Jews had been rooted in commercial life and exchange—at all levels, from money lenders and court Jews to peddlers and small artisan shopkeepers. This was not just because Jews had been excluded from other occupations, especially agriculture. Local and royal privileges clearly show that Jews were first invited to settle because they were already by and large a commercial people. Later restrictions only ratified and reified this reality. When Jews were finally granted legal equality in different parts of Europe from the late eighteenth through the early twentieth centuries, it was despite, not because of, their mercantile identities. Indeed, the implicit emancipation contract demanded that Jews diversify their occupations in order to blend in economically with the Christian population. In an important sense, this never happened; how could it when Jews were already urban and mercantile at a moment when the Western world as a whole was following suit? And what could be more enticing to them than a trade in new commodities not yet monopolized by non-Jews?

Having stumbled into the appraisal and sale of fine art, experienced merchants like Wildenstein and Joel Duveen were not about to leave their fortunes to chance. On the contrary, they and most of their counterparts among the first generation of Jewish dealers set about to systematically study the aesthetic qualities that made a work notable and distinctive. For these pioneers there were few textbooks; art history was in its infancy in the first half of the nineteenth century. Instead, they spent long days with eyes glued to the works adorning museums and galleries, sometimes with guides but just as often on their own, until they had acquired enough knowledge and discernment to know what to buy and how to price it.

Things were of course different for their sons—and occasionally daughters—who underwent lengthy apprenticeships and, often, formal training, before advancing to co-management of the firm. As with many ethnic niches, Jewish art dealing was a family affair. Like the German Jewish banking firms of the fin de siècle, business consolidation was often facilitated through strategic marriages. Still, the ethos was far from the claustrophobic one we associate with tyrannical patriarchs meticulously orchestrating the lives of their progeny. These were art dealers, after all, not “Our Crowd” bankers. Their business required them to fraternize with countercultural types and aesthetes and, just as importantly, to develop artistic taste. For some, such as Paul Rosenberg, dealing was a poor substitute for doing. “Paul,” Dellheim observes, “was a true art lover who bemoaned the fact that he was an intermediary rather than a creator.”

Artists, Jewish and otherwise, though naturally ambivalent and frequently kvetchy about their dealers’ supposed shortcomings, ultimately recognized how essential they were. Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler, a German Jew settled in Paris before World War I, played a critical role in bringing Picasso and his band of Catalan painters to the world’s attention. Picasso had his grievances, but “what would have become of us,” he wondered, “if Kahnweiler had not had a business sense?”

“The question of questions,” Dellheim poses, “is whether the role that certain Jews assumed in the art world—as dealers, collectors, critics, historians, and, not least, artists—was distinctive, and, if so, how and why.” Thankfully, Belonging and Betrayal, which clocks in at more than 650 pages, deals primarily with the art of the dealers, occasionally with the critics and historians, and only passingly with Jewish artists themselves.

The dealers deserve the book to themselves, since their story is crucial but until now hardly told. Dellheim shows that on the business side of things, Jewishness mattered not because common religious and ethnic origins invariably produced alliances between firms (on the contrary, competition was the norm), but because examples of individual Jewish achievement inspired other Jews to try to follow suit. Certainly, however, there were occasions when the familiarity born of shared identity helped. Thus, when Rodolphe Kann, a Jewish diamond merchant who’d accumulated perhaps the finest private art collection in Paris, died in 1905, his heirs rejected a prominent non-Jewish dealer and instead hired Nathan Wildenstein to sell the collection. “It is not surprising that they felt comfortable with Nathan,” Dellheim remarks. “He was, after all, a haut-bourgeois Jewish merchant who moved easily in their circles.” This is plausible, but it should be noted that one of the book’s few flaws is its failure to compare the relative strengths of Jewish and non-Jewish dealers.

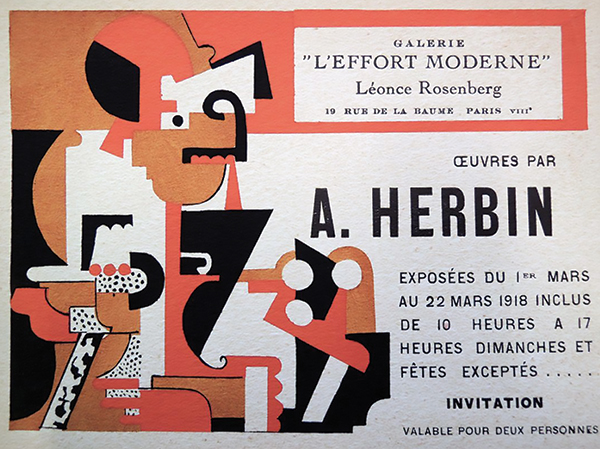

Although Dellheim is keen to show how outsider Jews advanced a modern art movement that was marginalized by the establishment, the truth is that there was no specifically Jewish affinity with aesthetic innovation. Some dealers specialized in old masters, others in Gobelin tapestries, still others in precious antiques. Indeed, it was the sudden cheap availability of old master paintings in the wake of the post-Napoleonic economic crisis afflicting the aristocracy that first opened the art market up to Jewish dealers. For every Léonce Rosenberg who self-consciously championed artistic modernism—pointedly naming his gallery L’Effort Moderne—there were more pragmatic dealers like his brother Paul, who hedged his commercial bets. As Paul would one day caution Léonce’s daughter Lucienne, “Don’t make the same mistake as your poor father did, restricting yourself to very avant-garde paintings.”

Still, there is no question that Dellheim is correct in his core assertion that the art establishment’s resistance to innovation, the exclusion of impressionists and cubists from the august academies, gave Jewish dealers an opening. Pierre Loeb, a dealer specializing in the avant-garde, even “claimed that four of five avant-garde art dealers in Paris in the years between the two world wars were Jews.” And indeed, the list of Jewish art dealers championing modernists is impressive, to say the least: Paul and Bruno Cassirer promoted the works of Monet, Manet, and van Gogh; Berthe Weill (one of the very few female dealers) indefatigably advanced the works of Picasso and Modigliani; the aforementioned Kahnweiler championed the cubists: Picasso, Braque, Gris, and Léger; Arthur Flechtheim boosted the paintings of Cézanne, Gauguin, Seurat, Rousseau, and Munch—and the list goes on.

One of Dellheim’s most fascinating and important insights is to illustrate the symbiosis of artistic modernism and capitalist entrepreneurship. It’s not just that Jewish art dealers helped prove the profitability of modern painting but that the market could serve as an alternative form of aesthetic validation outside the academy. As August Renoir remarked, “There’s only one indicator for telling the value of painters and that is the salesroom.” Renoir was no philosemite, but he was happily agnostic when it came to promoting his art. Needless to say, modernity by no means resolved—and at times actually heightened—the conflict between high culture and Jewish commerce. The conspicuous role played by Jewish mediators in brokering European modernity made them prime targets in the emerging culture war.

In a particularly deft chapter, Dellheim recounts how the illustrious art historian Bernard Berenson, born Bernhard Valvrojenski in a shtetl outside of Vilna, mastered Renaissance art while progressively distancing himself not only from the world of his failed peddler father but from Jewishness altogether. “For Bernhard Berenson,” Dellheim quips, “the assimilation of art and the art of assimilation went hand in hand.”

Berenson’s conversion, first to the Protestantism of the Boston Brahmins and then to the Catholicism of the Italian Renaissance art world he adored, is not itself blameworthy, but it went alongside his belief in the almost inherent artistic ineptitude of Jews and the assertion that they were capable only of imitation but not true originality, a charge similar to that leveled by antisemites such as Wagner and Drumont. Dellheim also tells the story of how Berenson misused his remarkable knowledge and skills as a means to profit financially through his undisclosed partnership with unscrupulous art dealers. “Berenson sold his soul to the devil for money rather than knowledge,” Dellheim concludes. “He became an art expert, a ‘valuer,’ who applied scholarly tools to commercial needs.”

Whatever complex evasions Berenson pursued in his aesthetic and financial dealings, he could not, in the end, throw the antisemites off his trail. Ensconced in his Tuscan villa, he and his art treasures narrowly escaped the clutches of the Nazis. Of course, most others were not so fortunate. Dellheim’s account of the fate of Jewish dealers and collectors is shattering but also the most familiar part of the book. One story that stands out is his recounting of the fate of Dr. Heinrich Rieger, a self-taught dentist and self-educated connoisseur who amassed an astonishing collection of works by Kokoschka and Schiele, among others, less by purchase than by barter. “Putting a personal stamp on ‘an eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth,’ Dr. Rieger offered poor, aspiring young artists dental treatment in exchange for art.”

The Riegers’ home in the Viennese suburb of Gablitz became a kind of salon and haven for art lovers and practitioners alike. Although some of Dellheim’s collectors and dealers managed to escape with their lives, or even, like Paul Rosenberg, with some of their art, the Riegers were ultimately trapped. Dr. Rieger’s last-ditch offer to serve as a curator to the fledgling Museum of Art in Tel Aviv was unaccountably declined. With no options to emigrate, the couple were forced to sell their precious collection, followed in September 1942 by their deportation and deaths in Nazi concentration camps.

Belonging and Betrayal is a brilliantly etched portrayal of the family firms that maneuvered, battled, adapted, persevered, and prospered over decades and centuries. What underlies all of Charles Dellheim’s painstaking research is a loving devotion to the subject matter. That means, above all, that his discussion of cultural and aesthetic matters rest on a bedrock of economic and business history. The element so often missing from studies of Jewish participation in Western culture here properly takes center stage. In this masterwork, Dellheim shows how to understand the business of culture.

Suggested Reading

The Great Gaon of Italian Art

Berenson’s teacher Charles Eliot Norton dismissively dubbed Berenson's method the “ear and toenail school,” but Berenson employed the technique in his first book to great effect.

The Rothschilds of the East

The Splendor of the Camondos and the pity of it all.

Is Beauty Power?

With charm, business savvy, and determination Kracow-born Rubinstein transformed herself from Chaja to Helena to “Madame.”

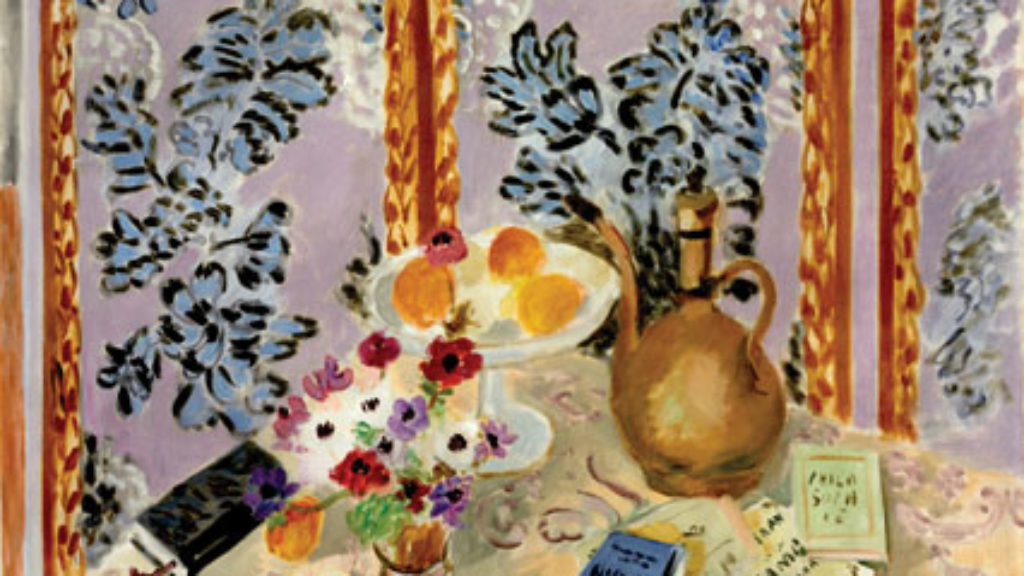

Matisse and His Jewish Patrons

Some of Henri Matisse's earliest and most committed supporters (and buyers) were Jewish. That might explain why Histoires Juives, a book of Yiddish jokes in French translation, and other Jewish items can be found in his paintings.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In