Matisse and His Jewish Patrons

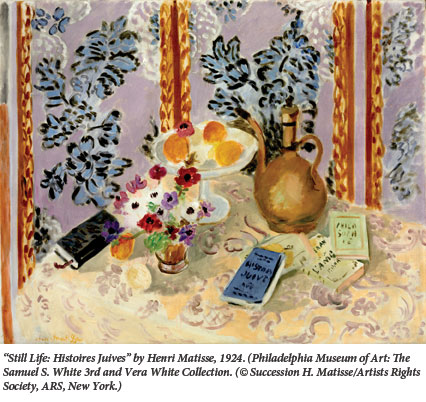

Only four still life paintings by Henri Matisse include books with legible titles. The most surprising of them anchors the objects in The Philadelphia Museum’s large “Still Life: Histoires Juives.” Histoires Juives is a volume in the Gallimard series Les Documents Bleus. The book’s editor, Raymond Geiger, described it as a collection of “stories with a moral, and narratives that belong to that treasure of popular Jewish folklore transmitted by oral tradition.” This might be a bit high-flown for the contents, which consisted of Yiddish jokes in French translation. For instance:

Two Jews had a rough crossing. A terrible storm sank their boat. An hour later, however, the two were on the shore, safe and sound. People were astonished:

“How did you swim ashore so successfully?”

“We didn’t swim.”

“Then how . . .?”

Gesticulating with their hands, they said: “We simply conversed.”

Or:

The old rabbi Mordechai is in heaven. Unfortunately, he never stops his disputations with everyone he meets. He harasses with questions Abraham, Moses, and even God himself. One day he said to the latter:

“Lord, tell me what a million years is to you.”

“To me? As one minute.”

“And a million pounds sterling?”

“A million pounds sterling? As one penny.”

“Then Lord, make me the gift of a penny.”

“Certainly. Wait . . . a minute.”

The fact that Matisse had this book—full of shtetl stereotypes—probably testifies to the fact that the artist was trusted by Jewish friends to enjoy the book’s crude humor without prejudice. An excellent mimic and raconteur himself, Matisse could be counted on to enjoy these stories about matchmakers; credulous or wily peasants; and disputatious, gesticulating merchants. It may have been a gift from one of Matisse’s Jewish dealers, who included Bernheim-Jeune, Léonce and Paul Rosenberg, Georges Petit, and Valentine Dudensing. But his relations with these men were never much more than cordial and occasionally contentious. It seems more likely that Matisse received the book from one of his early collectors, many of whom were also Jewish. In his first years of public ridicule, from 1904 to 1911, he forged lasting and intimate friendships with his earliest and most loyal patrons, the Stein family and, later, the Cone sisters of Baltimore. Two recent exhibitions and their accompanying catalogs tell the story—The Steins Collect: Matisse, Picasso, and the Parisian Avant-Garde, which opened at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art and recently closed at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, and Collecting Matisse and Modern Masters: The Cone Sisters of Baltimore, which opened at the Jewish Museum in New York and will be at the Vancouver Art Gallery through this summer.

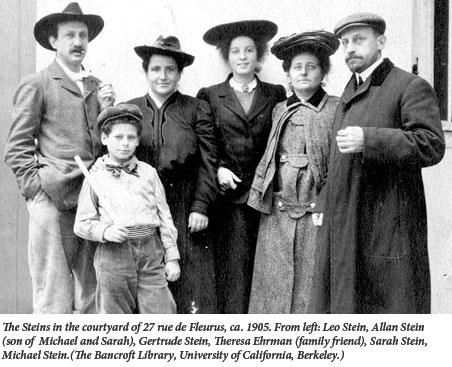

As his earliest patrons, the four Steins—siblings Leo, Gertrude, and Michael, and Michael’s wife Sarah—witnessed his efforts, listened to his professorial explanations, absorbed his experiments, and suffered with him when his work provoked derision. They bought “Woman with a Hat,” “The Joy of Life,” and “Blue Nude“ at the very moment gallery-goers were mocking them. Matisse frequently dined with them, attended their soireés, and even vacationed with them. As Americans and Jews the Steins were doubly outsiders to French society. Through their early purchases, the Steins themselves became notorious in Paris art circles and used this notoriety to create the avant-garde audience that made Matisse’s name.

Gertrude Stein, of course, wrote herself into the center of the group’s choices in her book The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas. In fact, she was the visual illiterate of the family. The ambitious and informative catalog for The Steins Collect, however, sets the record straight in two excellent essays on Leo Stein by Gary Tinterow and Martha Lucy. Gertrude had no pictorial sensitivity whatsoever when she arrived in Paris to live with her elder brother Leo, but she quickly absorbed both his interest in painting and most of his opinions. It was Leo who had labored the previous five years at “the work of seeing,” as he put it.

An aspiring painter himself, Leo was interested in art theory and the psychology of perception. He was, as Tinterow shows, a friend and intellectual peer of Bernard Berenson, the great art historian, with whom he often argued. The concepts of “tactile sensations” and “plastic values” were being explored in Leo’s Florentine circle, and he was able to apply them in his evaluation of Cézanne and later of the new work of Matisse and Picasso. He already understood the tension in Cézanne’s work between “the shifting planes and the resolute masses, spatial illusionism and the flatness of the picture plane.” In Paris, Leo was the acknowledged connoisseur of the new art.

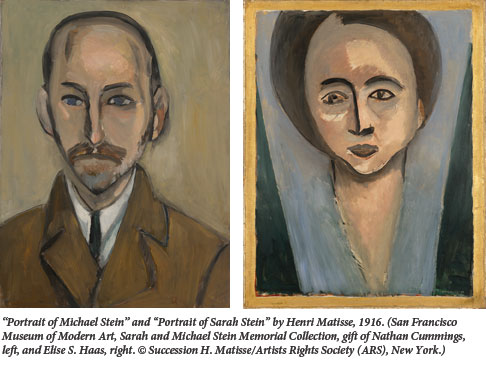

But the person Matisse called “the really intelligently sensitive member of the family” was Michael Stein’s wife, Sarah (Sally) Stein, née Samuels. He had the deepest respect and most tender regard for this married, matronly contemporary with her plain, alert, kindly face, rimless glasses, and halo of frizzy hair. If Matisse was her “religion” as Claudine Grammont’s catalog essay has it, then Sarah Stein was his patron saint. Shortly before the artist’s death, Matisse sent her a book by way of an American visitor with the inscription: “To Mme. Sarah Stein, who so often aided me in my weaknesses.”

Before coming to Paris, Sarah drew and painted, studied psychology and art criticism, collected art, and presided over something of a salon in her native San Francisco. She and her husband brought their fine collection of Japanese and Chinese prints with them to Paris. Michael was interested in architecture, commissioning an Arts and Crafts—oriented architect to design his innovative rental flats in San Francisco. When they arrived in Paris in January 1903, Leo guided them through the city’s museums and galleries.

At their apartment on the rue Madame, Sarah assumed Leo’s role in explaining the work to visitors. It was also Sarah who initiated and managed the school that Matisse opened in 1908, the Académie Matisse. Sarah took careful notes on Matisse’s instructions to his pupils, which were later published by Alfred A. Barr in 1951, after her death. Sarah and Michael also lent their paintings freely to exhibitions in order to enhance Matisse’s reputation, especially in the United States, where she proselytized for new believers.

Matisse responded eagerly to this unconditional homage. He brought his paintings to Sarah, asked for her opinions, and discussed his aspirations and his doubts with her. As a young eyewitness, Theresa Ehrman, recalled:

She was the one who fascinated him with her sense of appreciation of values among all who came to see his paintings . . . Sarah would tell him what she thought of things, sometimes rather bluntly. He’d seem to always listen and always argue about it, and I must say, I was sometimes quite bored because the conversations were very lengthy and very philosophical and sort of beyond me.

Ehrman wasn’t exaggerating. After she had seen a version of his 1911 painting, “The Artist’s Family,” Sarah wrote the artist a characteristically candid and penetrating letter.

As for the family portrait . . . for me, there are contradictions in the treatment—which take away from its sincerity of expression; it’s neither family portrait nor pure decoration. The profusion and dominance of the ornamentation undermine its status as portrait, while a certain intensity in some of the figures undermines its status as decoration—but I see by your letter that we’ll speak of all this.

This is a precise diagnosis of the artistic problem Matisse confronted. He was struggling to reconcile painting as a decoration, colored and flat, as is done in the Orient, with painting of a populated world, substantial and volumetric, as is done in post-Renaissance Western painting. After his experimental Fauve period (1904-1908), Matisse had branched into two modes of “decorative” painting—the mural-like figurative work he was doing for his Russian patron, Sergei Shchukin, (“Music,” “Dance,” “Game of Bowls”) and the highly patterned, tapestry-like paintings such as “La Dessert” and “Interior with Eggplants.” It was then, around 1910, that both Leo and Gertrude withdrew their support from Matisse. Leo turned to Renoir, Gertrude to Cezanne and Picasso.

Although Gertrude first described “Three Lives” as having been written under the influence of “Swift and Matisse,” she later eliminated Matisse and claimed that it was really looking at Cézanne’s “Madame Cézanne with a Fan” that stimulated her writing. The catalog essays on Gertrude Stein emphasize her relationship with Picasso, whose flouting of pictorial tradition gave Gertrude the permission to write Tender Buttons, the work that kicked away the scaffolding of 19th-century genres. Along with that scaffolding, she rejected Matisse, and sold all of his paintings.

Sarah and Michael Stein remained faithful to Matisse. In August 1914, most of their collection of Matisse paintings was on exhibition at a gallery in Berlin, when it was threatened with seizure by the German government, which was now at war with France. They hastily managed to sell the works to Swedish collectors, but were devastated at the loss. Matisse’s double portraits of Sarah and Michael in 1915 were a kind of compensatory gesture to them for this loss. (Gertrude resented the fact that Matisse never offered to paint her portrait.) The likeness of Sarah was transformed from a simple, descriptive likeness to a kind of icon in a gold frame, where her aura expands upward in an inverted triangle. Her round face is idealized in a gentle, ethereal visage dominated by far-seeing eyes. It is entirely possible that, as Sarah experienced a rush of clarity and energy, a “profane state of grace” in the presence of Matisse’s work, so the artist experienced inner certainty and calming reassurance in the presence of Sarah’s vibrant belief in him.

In 1926 Michael and Sarah commissioned a private villa from Le Corbusier, who was given a free hand to demonstrate the theories of his ideal of a house as a machine for living. “The house is clean and pure, far beyond anything we have done: a kind of obvious, indisputable manifesto,” he wrote to his mother about the villa. Carrie Pilto’s essay on the villa does justice to Michael Steins’ continued patronage of modern art. Once more, they were hosts to visitors who came to investigate and admire, including Matisse. Among the first visitors to the new villa were the Cone Sisters, Dr. Claribel and Etta, for whom the Steins often acted as European agents.

The Cones, whom Matisse called “my two Baltimore ladies,” had been collectors of the first hour. They attended the Salon d’Automne of 1905 when “Woman with a Hat” was purchased by Gertrude and Leo. Soon after, Sarah Stein brought Etta to Matisse’s studio, where she promptly bought two drawings and a painting. The sisters were to purchase some of the artist’s most important works in the next two decades. After Claribel’s death in 1929, Etta went on to amass more than five hundred works by Matisse, which are now housed permanently at the Baltimore Museum of Art. Their wealth derived from their family’s textile mills, which sold denim and corduroy cloth to companies like Levi Strauss.

Like Sarah Stein, the Cones were cultivated upper-class Jewish women who educated themselves in the arts, enjoyed surrounding themselves with beautiful objects, and traveled yearly to see and to buy. Claribel had a distinguished career as a physician, pathologist, and teacher. She spent extended periods in Germany doing research, while Etta, the younger sister, maintained the Baltimore household. The Baltimore salon of the Cone sisters at the turn of the century was the model for that of the Steins in Paris. Close to Sarah and Gertrude, Etta also became an intimate of Matisse’s wife, Amélie, and his daughter, Marguerite. The latter’s son (and Matisse’s grandson), Claude Duthuit, remembered that “even as a little boy, I felt that my mother, after seeing Miss Cone, was regenerated.” He added: “She had extraordinarily good, strong taste. The best of Matisse she bought, really.”

It is sometimes charged that Etta’s later purchases were unadventurous. As a single woman with strong female friendships, she was especially receptive to paintings of the female figure in a decorative interior, of two women together, or a single woman in the role of dancer, reader, painter, thinker. Nevertheless, when Matisse was bold, she boldly acquired. Etta’s purchase of the daring “Large Reclining Nude (Pink Nude)” of 1935 hung in her apartment facing her sister’s acquisition of the notorious “Blue Nude” of 1908. Her last purchase, “Two Girls, Red and Green Background,” was in 1949, the year of her death.

Matisse was especially responsive to the sympathy of these capable, independent-minded women who, like his mother, “loved everything he did.” The respectable tweedy Matisse found kindred souls in these upholstered Victorian ladies of his generation who departed from the conventional expectations of their times, as he himself did, only when they ventured into the uncharted territory of vanguard art. Like Matisse, their spirit of iconoclasm and their radical choices were grounded in the bourgeois respectability of traditional cultural values. The religion of art, with its ability to sublimate the baser instincts and provide a “disinterested” spiritual joy, was a vital aspect of the aesthetic movement of the period, and Matisse was as much a true believer in it as his acculturated Jewish patrons. Susceptible to the most modern fads and fashions of their day, they collected Eastern art and bibelots (the Cones by the trunks-full), vegetarian diets and self-help therapies, aesthetic theories and popular psychology, and, with the same firm faith in progress, they embraced the new in art.

Matisse worked alone. He belonged to no group, no school, no collective progressive endeavor. This made him a lonely figure who relied on his patrons for their appreciation and approval as much as for their financial support. Claude Duthuit remembered him saying, “If it hadn’t been for the Russians and the Americans, I would have starved.”

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

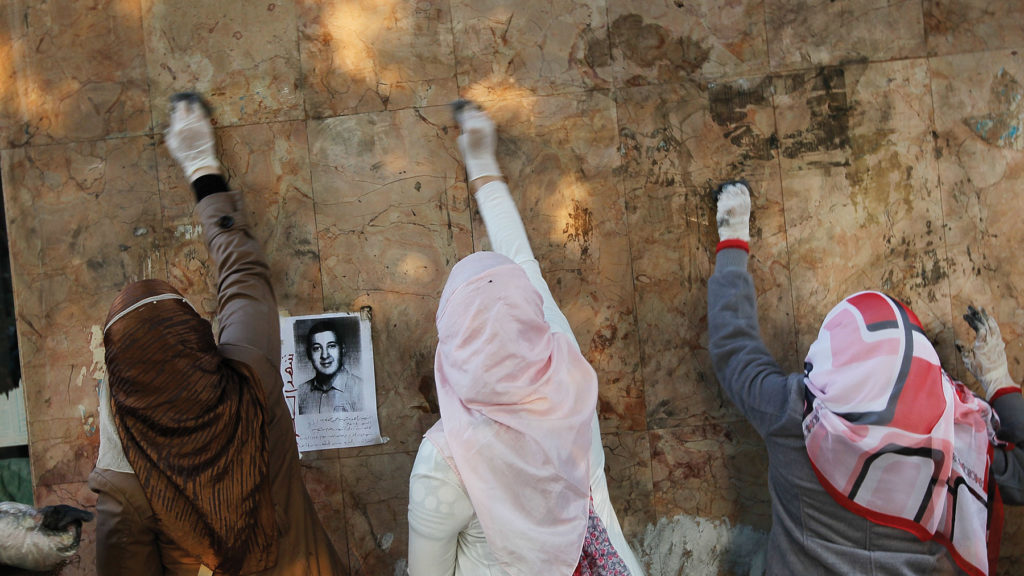

Trashing Dictatorship in Cairo

Tahrir Square isn't the only thing Egypt's democrats need to clean up before democracy takes hold in their country.

Pittsburgh Jews, Squirrel Hill, and the Tree of Life

In the wake of the recent massacre, a local historian tells the story of the Pittsburgh Jewish community and the 154-year-old Tree of Life synagogue.

Prospects for American Judaism

A new book traces the path of American Jews from participation to affiliation.

The Wandering Reporter

Read 86 years after it was originally published, The Wandering Jew Has Arrived can be seen as a chilling and prophetic piece of historical reportage.

etha999

Very interesting

I found this review after recent extensive exposure to M art and its background, context.

So I know these names but to read much more of detailed relations is v interesting.

M is a far more intriguing a painter than I realized.

Yes a painter who in a sense looks old fashioned but who definitely speaks to the Modern, to life today.

But he’s mercurial, seeks yes a balance, ultimately balancing the aesthetic and the moral, but in no precise way. A bit like the Heisenberg Uncertainty Principle. Maybe varies for each of us.