Think Over My Lesson and Try to Destroy It

Shortly after the Second World War, a twenty-something Elie Wiesel was sitting on a train in France, preparing to teach a passage from the book of Job to a group of fellow Holocaust survivors in Taverny. A poorly dressed acquaintance who was on the train asked Wiesel what he was going to say. When Wiesel told him, he replied: “Poor Job, as if he hadn’t already suffered enough without you!” Wiesel was humiliated: “I had lived for nothing, cheating, lying to myself. . . . Like Job, I cursed the day I was born. . . . The hobo found this amusing.”

Still, Wiesel was transfixed by the man. He became a dedicated student of the mysterious Monsieur Chouchani.

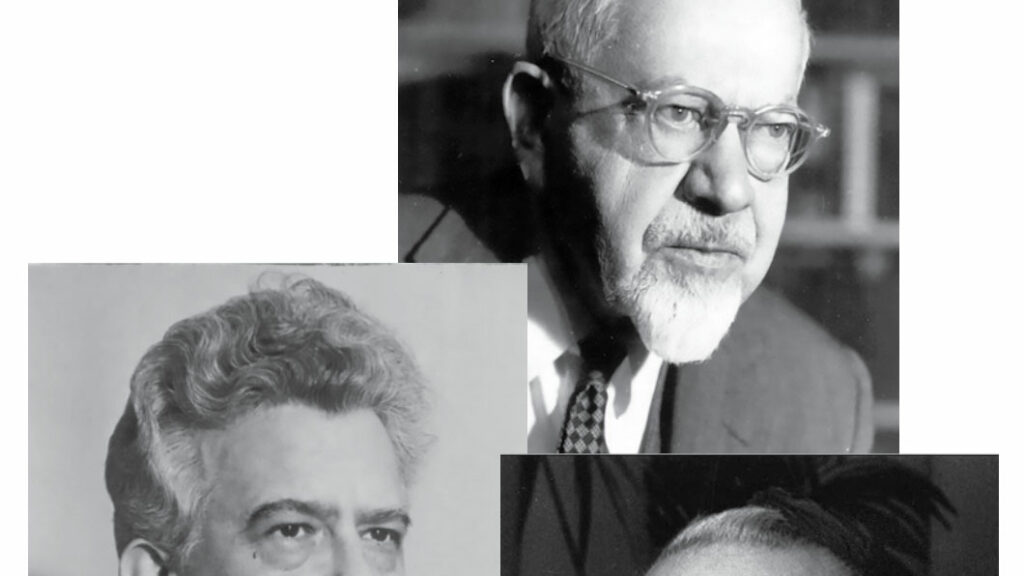

Wiesel wasn’t the only significant twentieth-century Jewish thinker transformed by an encounter with Chouchani. According to a perhaps-apocryphal story, the great philosopher Emmanuel Levinas initially refused to meet Chouchani for two years, despite the encouragement of a mutual friend, reasoning that an anonymous vagabond would have little to offer a philosopher such as himself, who had studied with Husserl and Heidegger. When the two men finally did meet, they talked all night. Afterward, Levinas told his friend, “I cannot tell what he knows, all I can say is that all that I know, he knows.” He spent the next five years studying with Chouchani and the rest of his life engaged with the Talmud as a source of philosophical insight. Other students included the Hebrew University philosopher Shalom Rosenberg and the distinguished French Jewish intellectuals André Neher and Rabbi Yehuda Leon “Manitou” Ashkenazi.

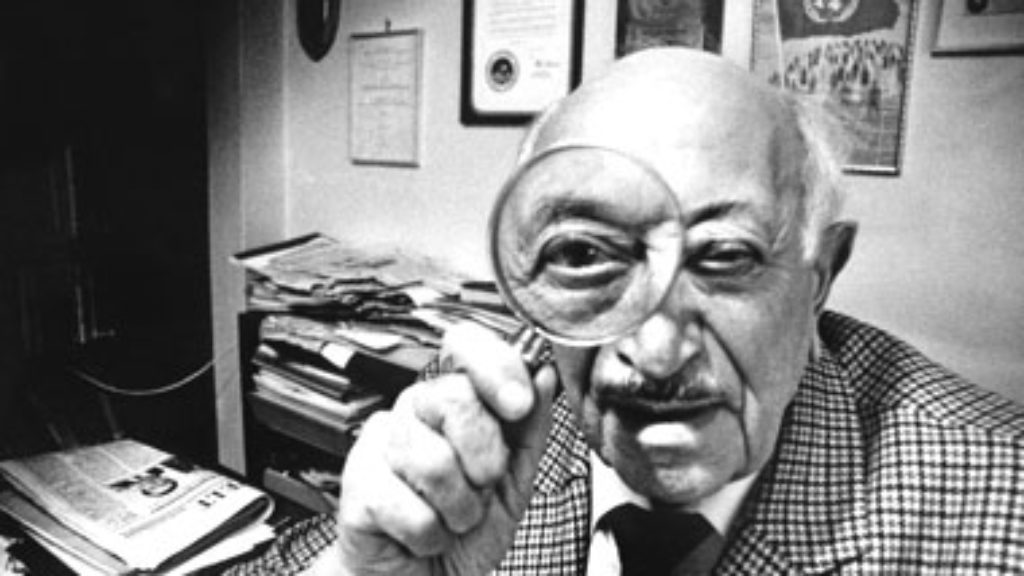

It is hard to figure out what drew such varied and brilliant thinkers to this man. Frustratingly, when Wiesel, Levinas, and Rosenberg described their meetings with Chouchani, they said almost nothing about the content of his teachings. Apparent genius, vagabond, and Yoda avant la lettre, Chouchani dressed poorly, paid little attention to his hygiene, and could be more than a little unkind to his students, often castigating them for their ignorance and leaving abruptly without saying goodbye. Stories told about him describe an enigmatic, manipulative, and belittling mentor. Could Wiesel, Levinas, Rosenberg, Ashkenazi, and Neher—each a brilliant intellectual with wide experience and a deeply moral personality—have fallen for the manipulations of an abusive narcissist?

Clearly, part of Chouchani’s attraction was the air of mystery that surrounded him. He revealed nothing of himself (Chouchani wasn’t even his name), left no publications, never stayed in one place for very long, and seemingly had no property other than what he carried around in a single suitcase.

His nomadic life apparently began in childhood, when his father tried to profit from him as a kind of intellectual circus freak, having him perform feats of memory in front of amazed crowds in Lithuania. In the years that followed, Chouchani memorized vast swaths of the Jewish canon—from the Bible to rabbinic literature to Jewish philosophy. He spoke an extraordinary number of languages fluently and, according to legend, would speak with the accent, intonation, and local dialect of whomever he happened to be speaking with.

Reportedly, he survived the Holocaust by, among other things, disguising himself as a Muslim, able to recite sacred Islamic texts by heart, and pretending to be a professor of mathematics. It would seem that the only constant in Chouchani’s life was movement, as he fled—from the Nazis and his own demons—from Lithuania to France, North Africa, Israel, the United States, and, finally, Uruguay, where he died in 1968.

Almost everything about Chouchani is a mystery. Even his closest students claimed not to know his real name. Wiesel once suggested that it might have been Mordechai Rosenbaum, but either he was mistaken or he was deliberately disguising his master’s secret. Historian Yael Levine has determined that he was actually Hillel Perlman, a Lithuanian yeshiva student who had studied with Rabbi Abraham Isaac Kook in Palestine in the early twentieth century. But this tells us little. Perlman is also a mystery.

Despite the curiosity of scholars and enthusiasts over the past half-century, most of Chouchani’s intimates have simply refused to share their knowledge of the man. Rumors have circulated widely among document hunters about a safe somewhere in Jerusalem in which four elderly gentlemen have deposited documents related to Chouchani—and signed an oath of secrecy, promising not to allow anyone to see its contents. (I have also heard rumors of those who have seen the contents of the safe nevertheless.) During the years I spent trying to track down that collection for the National Library of Israel (NLI), I met dead ends, suspicion, secrecy, and virulent opposition to the very idea that someone might have the chutzpah to publicize anything about Chouchani.

The situation changed dramatically in 2019, when six simple school notebooks in Chouchani’s own handwriting appeared for sale at a public auction in Jerusalem. Naturally, neither the auction house nor anyone else would say anything about where they came from, who was selling them, or what they might contain. In the end, the NLI and other public institutions were outbid, and the notebooks were sold for some $20,000 to individuals who later told me that they hoped to drum up enthusiasm and resell them for a profit. Those notebooks are still hidden from the public.

This inspired Rosenberg, who had studied with Chouchani in South America and been present at his death in Uruguay, to make a bold decision. Rosenberg donated nearly one hundred notebooks to the NLI, which scanned and cataloged them. Later, a website appeared (mr-shoshani.co.il) that includes scans of tens of other notebooks, whose source requested to remain anonymous.

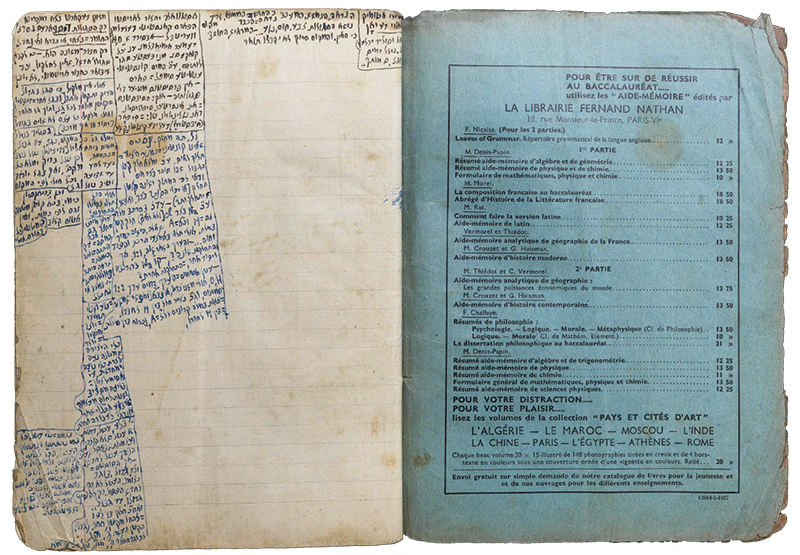

The notebooks themselves are simple Uruguayan and Hebrew school exercise books. Some pages are filled with long lists of seemingly random numbers. Were these memory exercises, calculations of some kind, or a way for Chouchani to keep his hands busy while doing something else? Many other pages are covered in tiny, barely legible Hebrew handwriting, with almost no space between lines. Some pages contain notes and summaries of things he was reading or studying, whether Torah, physics, mathematics, or astronomy. Others contain summaries of recent research on nutrition, his exercises while learning Spanish, summaries of events in European history, and other miscellaneous topics. Personal information, however, is rare, and fully formed deep thoughts, if they are there, are hard to find.

The most intriguing sections of Chouchani’s notebooks contain notes on talmudic passages and biblical verses. But these passages are nothing at all like essays, or even study notes, that one might sit down to read. There are few full sentences, let alone thesis sentences or coherent paragraphs. The notebooks are written in a kind of shorthand, with many abbreviations and only the faintest of hints to the biblical, talmudic, and later sources that are under discussion.

Dr. David Lang (the archivist at the NLI who cataloged the archive) and I spent weeks painstakingly transcribing, studying, and trying to unpack a section of fewer than 150 words. It contains implicit references to dozens of biblical verses and talmudic passages and has something to do with the metaphor of being a servant or slave of God and what it means to be such a servant in a fatalistic universe.

During those weeks we were caught up in the excitement of finally meeting the man behind the legend—of being one of the select few to be allowed, even by proxy, into Chouchani’s inner circle. The challenge of unpacking the master’s shorthand, of teasing out the barest hints of classical Jewish sources and stringing them together into what might be a coherent train of thought, energized me. It was enormously exciting to feel, even secondhand, something of Chouchani’s intellectual charisma. Still, that’s a far cry from saying I understand what he meant.

In fact, we couldn’t even determine whether the passage reflected his own original thinking or if he was summarizing a sermon he had heard or an essay he had read from someone else. At one point, after suggesting (I think) that even evildoers are God’s servants, for they bring about His will, Chouchani speaks of what is left of meaning and value in a world of suffering that has been caused by God. He calls on the reader (or himself) to accept the yoke of heaven before accepting the commandments: “For the will equals a person’s only property.”

The suggestion that human beings and the forces of nature do God’s will whether they are aware of it or not—and that consequently the world, even or especially the post-Holocaust world, contains God-induced suffering—is provocative. So is the related notion that the will is the only thing a person truly possesses—and that he or she is obligated to sacrifice it to God. But what exactly does it mean? Is Chouchani urging a cold Spinozistic acquiescence to a deterministic universe or a Kierkegaardian leap of faith? Or might he just be expressing the commonplace Jewish piety that one must accept divine providence? All of the above? None of the above?

Perhaps Chouchani himself wasn’t sure. It is certainly too early in the study of his writings to answer such questions. Then again, perhaps the notebook writings are too scattered and telegraphic for us to ever know. Was it even the purpose of these notebooks to express philosophical and theological arguments or only to gesture at them?

One of the few genuinely academic treatments of Chouchani’s thinking is Hodaya Har-Shefi Samet’s 2016 MA thesis on his hermeneutics, based on notebooks to which Rosenberg gave her early access. Chouchani, she suggests, emphasizes close reading and interrogating each word and wrinkle in a passage. As he wrote:

Carefully measure words, expressions, order, and change [in the passage]. . . . Pay attention to any curiosity in a verse or statement. The question is the entry ticket into the palace of knowledge.

And yet this could have been said by anybody from the early rabbinic sages to Renaissance humanists to the New Critics. Is it a profound insight into the mind and practice of a great exegete? Or just commonsense advice for any close reading of anything?

The Israeli world of Jewish studies has been in a tizzy over these now-open notebooks. Could we finally solve the mystery of Chouchani? How did he approach the act of reading and teaching? What did he think about God, commandment, faith, or suffering? Was there an original philosophy behind all the stories and secrecy? Might there be commonalities in the thinking of Levinas, Wiesel, Rosenberg, and others that stemmed from their shared experience as Chouchani’s students?

These are questions worth exploring, and Chouchani is clearly a key figure in the story of postwar Jewish thought, but I do want to suggest caution. The enthusiasm of discovery can easily lead to overreading. We might confuse a half-developed sentence fragment for a fully developed thought. We might convince ourselves of the profundity of Chouchani’s writings before actually finding evidence of it.

A short article in a festschrift for Rosenberg has a story about Chouchani’s surprise visit to an engagement party in 1953. Excitement was in the air when the already legendary man entered and offered to deliver a devar Torah, a homily in honor of the couple. This is one example in which those who met the man shared not only the encounter but the content of what he said, and . . . it’s a real letdown.

Chouchani made a pun on a biblical verse, which depended on reading it with a thick Lithuanian Yiddish accent. The moral of his talk was that one should be modest and unassuming. This is, no doubt, good advice in general, and for a young couple in particular, but hardly the stuff of genius. It is also frankly inconsistent with what we know of Chouchani’s own personality. It’s not that there is anything wrong with a quick, anodyne vort (word) in honor of newlyweds. But unfortunately, it does not help us understand who the mysterious Monsieur Chouchani, or Hillel Perlman, was.

Even if the notebooks are eventually fully transcribed, unpacked, and deciphered, we may never understand the source of Chouchani’s extraordinary intellectual charisma. The interpretive methods by which some future scholar might analyze the content of these gnomic writings were never designed to reconstruct the immediacy of a meeting with a flesh-and-blood teacher. If, as his students seem to imply in their stories, the primary message of Chouchani was the extraordinary man himself, then no “Written Torah” can ever replace the “Oral Torah” of the encounter.

Perhaps this is part of what Wiesel meant when he paraphrased the last thing Chouchani ever said to him: “Think over my lesson and try to destroy it.”

Suggested Reading

Simon Wiesenthal and the Ethics of History

Was Simon Wiesenthal an intrepid hunter of mass murderers? Or was he in fact more of a charlatan than a hero? Tom Segev's new biography of the most successful—and controversial—Nazi-hunter raises more questions than it cares to answer.

Between Literalism and Liberalism

While literalism is intellectually untenable and liberalism is numerically imperiled, many Jews find that what they believe cannot be transmitted, and what can be effectively transmitted they cannot believe.

A Stolen Seat

“Good Shabbos—you’re sitting in my seat” takes on a whole new meaning when it’s your brother- in-law talking. From a Russian Jewish diary, with an introduction by Alice Nakhimovsky and Michael Beizer.

A Stone for His Slingshot

In 1948 screenwriter Ben Hecht lectured “a thousand bookies, ex-prize fighters, gamblers, jockeys, touts,” and gangsters on the burdens and responsibilities of Jewish history. The night at Slapsy Maxie’s was a big success, but the speech was lost, until now.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In