The Fierce Lust for Contemplation

Once upon a Purim back in my yeshiva days, I sported a jacket with elbow patches, took up a pipe, and carried around a tattered edition of Bialik’s Hebrew poem “Ha-masmid” (The Dedicated Student), which I declaimed in the original Ashkenazi pronunciation. My costume wasn’t risqué, yet it still elicited squirms and nervous laughter from my black-hatted peers, who were startled by the incongruity of a shaggy, bareheaded maskil (I had donned a professorial toupee) walking the yeshiva’s halls. The real joke was that a century earlier the yeshiva was precisely where one found maskilim like Bialik. And, of course, like a kid dressed up for Purim as a princess or a punk rocker, my drag revealed more of my inner life than it masked. The transition from yeshiva bochur to poet (or professor) can seem radical and rending (it did to me). But is it?

How did modern Hebrew literature suddenly arise from a half-dead Semitic language—a language that was not even quite spoken yet? And how should we understand the relationship between largely religious premodern Hebrew literature and the secularizing modern Hebrew poems, essays, novels, and memoirs that Eastern European Jews began to write in the second half of the nineteenth century? Or to put the question in biographical terms, what are we to make of the two main phases in the lives of these modern Hebrew writers, unfolding first within and then beyond the yeshiva?

The exodus of yeshiva boys from dank study halls to bustling European capitals, from the beis medresh in Volozhin to the coffeehouses of Odessa, is a key narrative of modern Hebrew literature. The dominant approaches in Hebrew studies conceive of this literary birth as a clean break with the traditional past and a progression toward secular Jewish culture or the burgeoning Zionist movement. While scholars have acknowledged connections between traditional Jewish learning and modern Hebrew literature, they have not tended to focus on it. In the extreme position, the modern Hebrew literary project is seen as about as similar to premodern Hebrew writing as Spinoza’s Tractatus is to a talmudic tractate—which is to say, only in name.

In The Yeshiva and the Rise of Modern Hebrew Literature, a short monograph with a bold thesis, Marina Zilbergerts offers another possibility. In her view, despite the complex transformations that Hebrew literature and its writers endured in the later nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, there was a kind of alchemical conservation of energy at work. Of course, the redeployment of a sacred, scholastic language to forge a politically charged, sometimes sensuous, and frequently transgressive literature was revolutionary. Yet, Zilbergerts insists, despite the secular shift in the themes and tenor of the new Hebrew literature, “this revolution originated in the world of tradition”: the rabbinic ideal of pure intellectual devotion to even the most obscure traditional texts was secularized into a radical commitment to writing pristine prose in a largely inaccessible language. The Masmid who, “when, in the vigil of winter night, / He triumphs o’er a problem that has drawn / The marrow from his brain, then is his joy,” becomes the Hebrew writer who troubles over his lines to triumphantly represent the world and make Hebrew modern.

The Yeshiva and the Rise of Modern Hebrew Literature is a blessedly jargon-free book, though Zilbergerts does deploy one fancy term, “autotelic” (“having a purpose in and not apart from itself”), to precisely name this brand of intellectual piety. Intriguingly, she compares European autotelic ideas and slogans, most famously, “art for art’s sake,” with the Eastern European rendition of the rabbinic ideal of Torah lishmah as the study of Torah for the sake of the Torah. Identifying this apparent common denominator doesn’t mean that Zilbergerts’s argument is a simple equation. For one, the autotelism that first powered modern Hebrew literature briefly turned into its greatest liability, when social utility became a key measure of literary value. Further, the yeshivishe notion of “Torah for its own sake” and the institutional setting of large Eastern European yeshivas that supported it was not entirely a traditional position (originally, the phrase “Torah lishmah” just meant Torah study undertaken for pure, religious motivations) but was itself a modern development. Despite the historical twists and turns that her argument must take, Zilbergerts’s thesis retains a powerful simplicity. Modern Hebrew writing emerged in Eastern Europe as an enduring, modern literature in part due to the persistent traditionalist commitments of its first writers.

The Yeshiva and the Rise of Modern Hebrew Literature opens with a grand view of the great nineteenth-century Eastern European yeshivas, especially Yeshivas Etz Chaim in the White Russian town of Volozhin, which was established in 1803 by the Gaon of Vilna’s student, Reb Chaim. Volozhin and its peer institutions were religious edifices built on centuries of rabbinic scholarship, yet in some respects they represented something quite new. In the past, most Eastern European yeshivas had been integrated into the fabric of the community with their local rabbis, petty politics, and rickety economies. But as these institutions grew in size and reputation, they achieved a level of independence that distanced gown from town and nurtured an ivory-tower conceit in which the students’ unwavering devotion to intricate talmudic texts was the most important thing in the world.

Such yeshivas were not rabbinical trade schools, nor were they invested in issuing rulings on practical areas of Jewish law. In some sense, impracticality was precisely the point. According to the metaphysics of Torah lishmah, engaging with the divine text was a cosmic activity on which the cosmos turned. This was, in effect, a hyperliteral reading of the first item in the Mishnah’s dictum, “Upon three things the world stands: on Torah, on Service, and on acts of loving-kindness,” which gave way to strikingly monkish practices, such as continual study shifts—all day and all night—scheduled to keep the world going.

This romantic scholasticism had its passionate adherents and theorists but also attracted critics, both inside and outside the yeshivas. Maskilim had been agitating against extreme dedication to talmudic studies since the eighteenth century, which, they argued, consigned the Jewish community to gloomy medievalism and held them back from emancipation and integration. There were also material concerns: who would support and feed the Masmid and for how long?

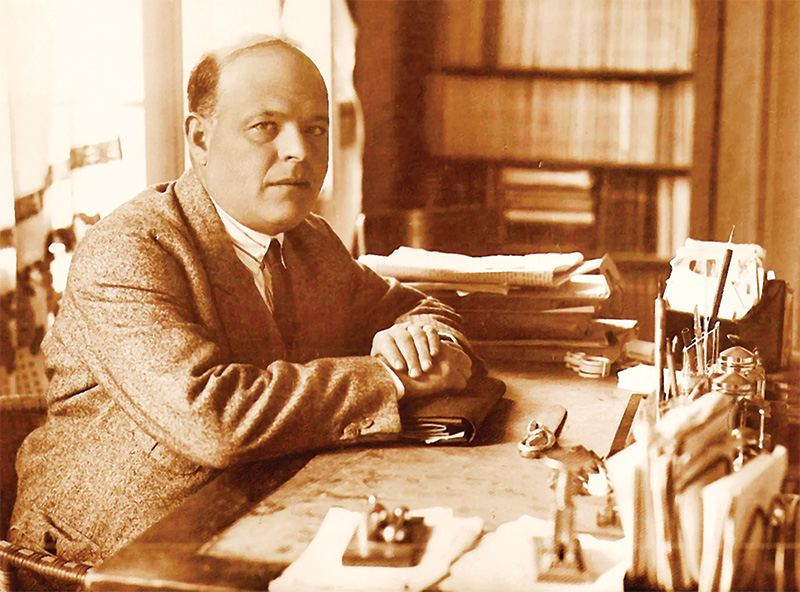

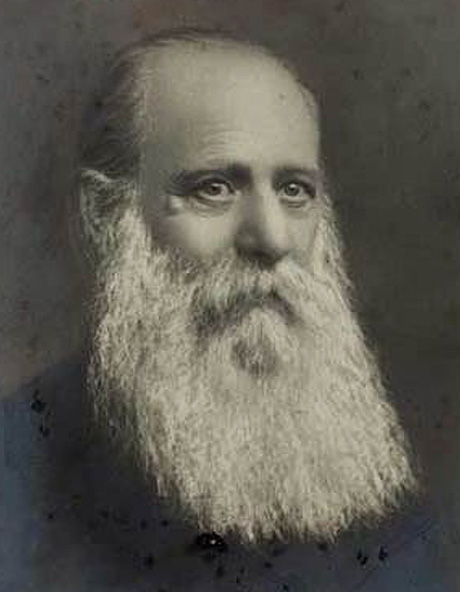

Zilbergerts follows the careers and key works of five rising talents as they left yeshiva, attempted to break free, and wrote their way, in bejeweled Hebrew, through the metamorphoses. We meet the Kovner brothers, Avraham Uri (1842–1905) and Yitzhak Aizik (1840–1891), and their saber-sharp pens; Moshe Leib Lilienblum (1843–1910), the author of the influential novel The Sins of Youth (Ha-ta’ot Ne’urim), which helped establish the template for future “off-the-derekh” memoirs; the Nietzschean Hebraist and Volozhin graduate Micha Yosef Berdichevsky (1865–1921); and finally, themost important Hebrew poet of the last century, Chaim Nachman Bialik (1873–1934), who decided to study in Volozhin after reading Berdichevsky’s (exaggerated) description of the institution as a free-thinking hothouse. A few years later, Bialik would write his paean to the “Dedicated Student,” who represented the old Volozhiner ethos while gesturing toward the emerging Hebrew literature.

Zilbergerts gives the biographies of these five men (women were largely excluded from modern Hebrew literature because of their traditional marginalization from rabbinic learning) a Hegelian plot, in which literary thesis gives way to materialist antithesis, which is resolved in a hard-won synthesis. Her thesis is that even when classical Hebrew texts shed their religious enchantment, the new Hebrew literature, as a set of Jewish texts, retained some of the old magic.

Yeshiva life, and Jewish life more generally, was an imaginatively rich existence, with an abundance of fictions—mainly of the legal sort—and a preference for proof text over prosaic existence. (The famous Yiddish [and Hebrew] writer Mendele Mokher Seforim once satirized this by telling the story of shtetl mavens who, upon being introduced to a juicy exotic fruit, resorted to scripture to confirm its existence.) Even when budding Hebrew writers abandoned rabbinic learning and engaged in newfound secular pursuits, they continued to voraciously read texts and spin new, beguiling webs in an updated version of rabbinic Hebrew. In this way we get Berdichevsky’s indelible image of a formerly pious yeshiva boy holding a midnight study vigil, only now it is a secular Hebrew book over which he pores.

The antithesis came swiftly, first in the form of hungry bellies and bare cupboards. Leaving yeshiva meant abandoning its system of financial support, yet writing in a language with a tiny readership was not going to pay the bills. This was not only a personal predicament but a growing communal problem. As the second half of the nineteenth century progressed, materialist critiques of the yeshiva world, which had been honed for years by maskilim, became charged with radical new ideas from the new young Russian intellectuals known as nihilists. What mattered now was the real, grounded world, its wants and needs, not otherworldly, pilpulistic “towers hovering in the air.”

Russian nihilists favored prose over poetry and disliked aesthetics of any sort, arguing that the most important aspect of the new, realist literature was not artistic talent but revolutionary utility. If the chief attraction of modern Hebrew writing was its stark beauty and dense layering, where did that leave it? If the purpose of literature was to answer Nikolay Chernyshevsky’s famous titular question “What is to be done?” then shouldn’t Eastern European Jewish authors be writing in a widely read language like Yiddish, or even Russian—the language of the land—rather than in an elite, scholastic tongue?

The ex-yeshiva intellectuals, who began devouring nihilist pamphlets with the same gusto with which they had previously consumed rabbinic literature, were excited and impatient. Lilienblum compared Jewish writers and intellectuals to their Russian counterparts:

While the intellectual world of the Russians is rattled by the fresh ideas of Chernyshevsky and Pisarev, our respected writers are sitting, their hands covered in ink, trying to shock the world with a banal clarification of scripture, poring over an ancient book that is already falling apart—both its binding and its ideas. . . . Give us bread! Give us the air of life!

Zilbergerts draws intriguing parallels between the new Hebrew writers and some of the Russian nihilists, who had also grown up in the (Russian) Orthodox educational system in which students engaged in something like Christian pilpul (the young Russian writer Nikolai Pomyalovsky called this “one hundred tricks of sophistry and parabolism”). She also does a good job of capturing the painful, self-destructive absurdities of Hebrew polemics against Hebrew literature. As Zilbergerts points out, Lilienblum’s “break from Jewish observance and from the Orthodox community had surprisingly little effect on the writer. Instead . . . the great drama . . . is Lilienblum’s loss of faith in texts and in the value of the literary pursuit.”

If the Kovner brothers had had their way, modern Hebrew writing would not have lasted more than a generation. When the older Yitzhak Aizik realized that Hebrew literature would never achieve materialism’s concrete goals of dignifying Jewish life with work and sustenance, he wrote bitterly of his fellow Hebrew writers that “their only wish and desire is to write more and more books to no end, which satisfy only their love of themselves.” Interestingly, it was the turbulent, successive waves of European intellectual life and the disappointments of post-yeshiva existence that rendered nihilism passé and helped the Hebrew literary vessel regain its bearings. The late nineteenth century saw, among other developments, renewed interest in religious tradition and symbolism, which were appreciated as possessing fresh artistic possibilities. There was also Friedrich Nietzsche’s powerful, frightening vision, which injected vitality into the veins of writers in various literary traditions, including Hebrew.

In the fin de siècle, Hebrew writers quickly awoke from their brief, dry dream of literary utilitarianism. In any case, their new lives in materialist meccas like Odessa disappointed them greatly. The city’s “enlightenment,” wrote Lilienblum, “bears an air of cool freedom, borne of commerce and hedonism, [which] is founded in self-deception rather than inner enlightenment, produced by deep reflection.”

Lilienblum managed to stake out a tenable position for himself, in which labor and a brave new worldly Torah could coexist. In a rewritten Mishnah mixing materialism with a modified Torah lishmah theology, Lilienblum invented a new rabbinic maxim and attributed it to Elisha ben Abuyah, the rabbinic arch-heretic:

Upon three things the world stands: On Torah, on labor, and on charitable deeds. And Elisha ben Abuyah says: On the Torah and on labor. The inhabitation of the world [yeshuvo shel olam] is similar to its creation. It [the world] has been created by Torah and labor; hence it must be inhabited through Torah and labor.

For his part, Berdichevsky penned marvelous Hebrew prose sketches celebrating though ultimately condemning Jewish textual devotion as “the fierce lust for contemplation in the heart of the Jewish boy . . . a true picture of one who kills himself in the tent of knowledge.” Berdichevsky fought for a Nietzschean reawakening of the Jewish soul that overcame such pure bookishness, yet he still believed in the potential power of forceful Hebrew writing.

Of all the writers surveyed in The Yeshiva and the Rise of Modern Hebrew Literature, Zilbergerts is most sympathetic to Bialik, who struggled like all the rest but ultimately crafted a working synthesis that secured modern Hebrew literature’s future. Zilbergerts reads “Ha-masmid” and its creation as a heroic effort to navigate some of the minefields encountered by early modern Hebrew writing. Thus, she notes that in a precursor of the poem, Bialik riffed on a phrase made famous by the earlier maskil poet Judah Leib Gordon:

For whom do you toil, lost, miserable brother?

Your labor is belated; your work’s hour has passed.

Your field is scorched; your meadow, a salt flat.

But this materialist critique of traditional Jewish life was pointedly omitted from the longer final version of the poem.

Zilbergerts also reads a line describing a gust of air that tempts the poem’s studious hero (“It dances, curls his side-locks with a playful hand”) as responding to the growing Zionist desire to replace the pale and studious Eastern European Jew with a more robust specimen. In Bialik’s poem, the student successfully overcomes the winds of temptation, continues learning the sages’ teachings, and will finally reach his true purpose by becoming the “soul factory of the nation”—that is, the developing nation of Israel, with its new secular Hebrew literature.

In Zilbergerts’s conception, “Ha-masmid” becomes a great epic of transformation, in which the seemingly stale talmudic words of the past, such as “the matmid’s familiar song—‘Oy, Oy omar Rava, hoy omar Abbaye!’ . . . —is no longer a repetitive chant of the words of long-dead sages. This refrain becomes Bialik’s testament to the continued vitality of the rabbinic intellectual endeavor.” Now the same words point the way to Hebrew literary renewal. As Bialik put it, “He surely knows how students lived of old / He surely knows his day of fame will come.”

Zilbergerts’s readings of modern Hebrew pioneers like Lilienblum and Bialik are as elegant as some of the modern Hebrew texts she analyzes. Her writing is clear and concise, and the book is never bogged down by polemics with secondary literature or unnecessary references to primary sources. This occasionally results in infelicities, as in her treatment of the evolution of “Ha-masmid,” which at times ignores the philological facts laid out in Dan Miron’s critical edition of the poem. Zilbergerts is also uninterested in locating the autotelic qualities she has identified among modern Hebrew’s other influences, be they Hasidic storytelling, maskilic satirizing, or neopagan provocations.

Instead, like a hyper-focused yeshiva student reading Talmud, she tunes out the noise and draws our attention to the textual heart of the matter. Wallace Stevens wrote of a quiet house and calm world, in which everything else slipped away, and “the reader became the book.” Bialik describes the Masmid studying in the cool of the early morning like this: “The dawn, the garden, the enchanted fields, / Are gone, are vanished like a driven cloud, / And earth and all her fullness are forgotten. / Earth and her fullness are concentrated here.”

Suggested Reading

Proust Between Halakha and Aggada

Proust and Bialik were both great literary modernists, but they aren’t usually thought of together. Reading In Search of Lost Time in light of “Halacha and Aggada.”

Eight Poetic Fragments by Avraham ben Yizhak

Some of Abraham Sonne's lines are so gorgeous that one commits them to memory almost unthinkingly.

Shababshubap

Black hat chic: Shai Secunda's review of Shababnikim, the new television show about cool yeshiva students.

The Rogochover Speaks His Mind

After he visited the odd talmudic genius, Bialik said that “two Einsteins can be carved out of one Rogochover.”

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In