History—and Israel—from the Outside In

Although this has been an unprecedented season of protests and political conflict, when Israel’s seventy-fifth birthday arrives, the nation will, one hopes, celebrate it in what has become the traditional way: with peaceful celebration and nostalgic commemoration. Families and friends will assemble throughout the country for barbecues (mangalim), and the media will retell the story of how we got here, drawing heavily on archival footage. The scenes they describe and display will jog and confirm the collective memory. The Exodus will sail again. A wing of the King David Hotel will again be reduced to rubble. The British High Commissioner and his dog will again ride the boat that took him away from Palestine to the destroyer anchored in a distant corner of the Haifa harbor. This year, on the evening of April 25 (5 Iyar), the destroyer will again leave the territorial waters of Palestine. The flag of the newly independent State of Israel will be raised, and the armies of the neighboring states will again cross its borders in an effort to lower it.

All of these memories will focus on the local actors, especially the fighters. The fraught relationship between the organized, Labor-led leadership of the Yishuv, with all its internal divisions, and the numerically inferior forces of the dissident Irgun and Lehi (the “Stern Gang”) will be largely forgotten, for the conflict between them is of no consequence as far as the collective memory is concerned. The world of 1948 outside our corner of the Middle East will be cast in shadow.

This outlook has seeped into Israeli historiography as well. It has room almost exclusively for things that were visible on the ground in Israel, or things that took place elsewhere as they were seen from Israel, unconnected to matters that extend beyond the local picture. Even those historians whose research has ranged more widely have remained firmly attached to the Israeli vantage point. After venturing outside, they have invariably returned home, and the products of their research have retained a distinctively local flavor.

From this historical perspective, the great Zionist leader Chaim Weizmann looms artificially small. His principal sphere of activity, from the beginning of his career, but especially between 1945 and 1948, was outside the Land of Israel. Weizmann didn’t live in Palestine, not even after 1937, when he had a lovely home at his disposal in Rehovot. He made aliyah in the full sense only at the beginning of 1949, when he relinquished his British citizenship and immediately afterward was chosen to be the first president of Israel. On no small number of occasions, Weizmann’s outsider’s view of the Yishuv led to conflict with those whose lives remained Yishuv-centered even when they were busy overseas. And yet, it is precisely that perspective that historians (and arguably contemporary Israelis) would do well to recover.

In writing Weizmann’s biography, we have more than once found ourselves fascinated by his view of the Yishuv, its challenges, successes and failures, and especially its relationship to the world around it. This view led him to wider, sharper, more critical and realistic conceptions of the Zionist enterprise than his local comrades. Someone who spent most of his time far from the Land of Israel could view what happened there from a broader perspective, a viewpoint that became an effective political asset in the hands of the man who was the heir of Herzl and the teacher of Ben-Gurion.

It is impossible, we believe, to understand the rapid growth of the Yishuv and the creation of the State of Israel without the continent-spanning Jewish and non-Jewish political and social network that Weizmann strung together. He was a chemist and, above all, a political leader, not a historian. He certainly left no historiographical doctrine. But it is possible and permissible to draw conclusions from his political approach that apply to history in general, especially to that of the Yishuv and the State of Israel. Call this the outside-in approach to history.

Every society is sustained, in part, by its collective memory. This shared repository of images and narratives is preserved and transmitted in the home and at school; at museums, parks, and commemorative sites; in public ritual, pronouncements, and folklore; and through documentaries, popular entertainment, and now, of course, social media.

Such memories express the past in the local language of the here and now. Because memory always originates in the present, the seemingly historical story that it tells actually turns things around, placing the later first, and the first later. Causality, the foundation stone of historical discourse, is set aside to tell a story in which the end is predetermined and the heroes and villains (us and them) are clear.

The serious historian must set such just-so stories aside and, insofar as possible, become conscious of his or her own biases, limitations, and methods. Of course, one can never transcend one’s self, one’s historical moment, or one’s society. Nonetheless, one can reject the identification of “what was” with what is worthy or useful to remember now and attempt to retrieve the singularity of history, to recover what took place in the past and will never return again. In this regard it is extraordinarily valuable to view the local historical actors not only from their own perspective (in which history and memory are in danger of becoming hopelessly intertwined) but from abroad, as it were, and as a part of larger causal patterns. That is, to proceed from the outside in rather than from the inside out, as historical memory inevitably does.

Even the microhistory of a particular local event must be oriented toward the larger world, the macrohistory of which it is necessarily a part.

With this in mind, let us return to the end of the Palestine Mandate. Britain concluded its rule over Palestine in the middle of 1948 after the lapse of the mandate granted to it in 1920 by the League of Nations (and transferred to the United Nations in 1945). Why didn’t the British remain in Palestine? What prevented them from doing so? Central figures in Great Britain and America hoped for a continued British presence in the land, in one form or another. Was the very fact of their departure from the country proof that the British had been expelled from it? And if this happened, why were they expelled, and who expelled them?

Our Israeli collective memory highlights the fact that Britain did not want to see a state established for the Jews and showed this by its behavior in the post-World War II years. Beginning in this period and working its way backward to the Balfour Declaration in 1917, we have constructed a narrative in which illegal Jewish immigration and the war that the Yishuv waged drove the British from Palestine.

The British themselves receive little attention in the picture that memory paints here. The story revolves mostly if not entirely around the Yishuv’s response to the evils it undoubtedly suffered. And it does so by virtually erasing the internal differences among the Jews in Palestine, especially between the left-wing activists of the Labor Movement who led the Yishuv and those who rejected their leadership and established the fiercely anti-British Irgun and Lehi.

Historians who proceed from the inside out in telling this story naturally focus their attention on the struggle between the Yishuv and Britain, recorded in the Yishuv’s main archives. Even when they are not under the sway of collective memory, historians relying primarily on such documents tend to see the British Empire, and certainly London, as preoccupied with the Yishuv. They focus above all on matters such as illegal immigration, settlement, and violence (which is usually not called “terror,” on account of conscious or unconscious identification with the people who perpetrated it).

Without necessarily intending to do so, the historians who take this approach implicitly suggest that Britain had almost nothing else with which to be concerned in the tumultuous years after World War II than the problems posed for it by the Yishuv—that Palestine was more to the British than the corner of a vast and unraveling empire. Unfortunately, this inside-out approach echoes the collective memory not only in its distortion of the causes and circumstances of the British withdrawal but also in its oversimplification of the relationship between cause and effect.

Does the fact that Britain ultimately left Palestine under considerable pressure mean that it was simply thrown out? Sitting in London, Chaim Weizmann knew better, and we historians should as well.

History that proceeds from the outside in is less beholden to collective memory and better situated to interpret local events dispassionately. Historians, of course, can never be totally objective. In fact, the pretense of absolute objectivity damages our profession, but the outside-in approach facilitates a relative objectivity. Feelings, familial and cultural inheritance, education, politics—all of these things particularly challenge those who are occupied with the study of the society to which they belong. But it isn’t the task of the historian to strengthen or weaken collective memory or to fortify his or her own identity.

The history of the Yishuv is an outstanding example of a subject that benefits from an outside-in approach. Historians of the Yishuv and its transformation into the State of Israel should begin by zooming out to try to grasp the unique combination of necessary preconditions and long series of contingent circumstances that made this dramatic process possible.

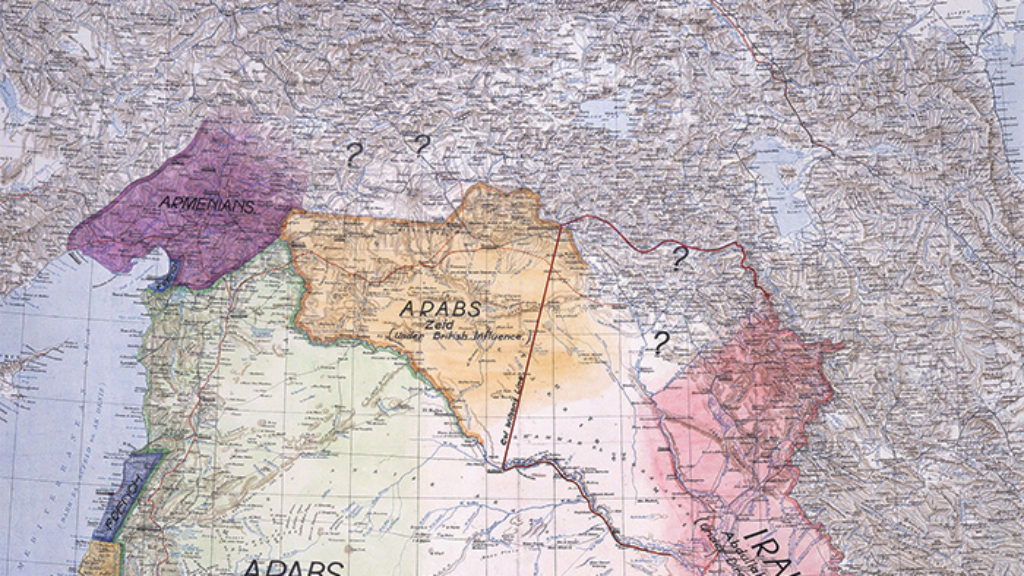

We do not have the space to review the broad historical background to the Zionist revolution and the renewal of Jewish life in Palestine, but here’s an exceedingly quick sketch: Social and political possibilities opened up to the Jews of Europe in the eighteenth and even more in the nineteenth century. This led to a westward migration of millions of Jews at the end of the nineteenth and beginning of the twentieth century. This period was marked by a series of global crises, climaxing in World War I, which was followed by the peace conference in Paris, the establishment of the League of Nations and its acquisition of sovereignty over imperial zones that had collapsed, and the unprecedented mandate system. The mandate granted by the League to Great Britain resulted in both a map of Palestine corresponding to its interests and the Arab-Palestinian awakening. This, in turn, was followed by the world economic crisis of 1929, the rise of totalitarian regimes, World War II, the horrors of the Shoah—and at the end, a window of opportunity with the advent of the Cold War, the dismantling of the British Empire, and the establishment of the UN and its decision to end the mandate.

In the context of these (and other) developments, the history of kibbutz Ein Harod, Nahalal, and even Tel Aviv simply cannot be seriously understood as autonomous stories, isolated puddles unconnected to the massive waves of world history.

A quick look at the biographies of the leading trio of Zionist figures is clarifying in this regard. Theodor Herzl lived and breathed the international system. The World Zionist Organization was transnational and transimperial because that is the world in which Herzl operated. He thought imperially, and, after his failure with the Ottomans and the Germans, he “discovered Britain” for the Zionists. His (failed) Uganda Plan was a bold effort that would have been unthinkable without the backing of Great Britain.

His successor, Chaim Weizmann, was not merely pro-British. He was, despite having been born in what is now Belarus, British in his entire being. He, too, lived and breathed a supranational system: that of the World Zionist Organization, of Great Britain, and of its empire. He also understood the new rising power of the twentieth century, the United States.

David Ben-Gurion, who rose to leadership in Palestine and was the most provincial of these figures, nevertheless underwent an impressive process of political education in the 1930s and 1940s as head of the Labor Party and the Zionist Executive. On the eve of the State of Israel’s establishment, and even more so afterward, he worked with a sharp awareness of the crucial importance of external international actors on the affairs of his small nascent state.

Zionist leaders, including Weizmann and Ben-Gurion and the other leaders of the Yishuv, were aware of the dependency of the Zionist project on Britain, the United States, the Soviet Union, and the UN, and they acted accordingly. A war against Britain was not on their agenda after World War II, or even before it. They did not simply expel the British from Palestine in 1948 any more than Gandhi had in the previous year.

What actually happened after World War II is incomprehensible without considering the mood of Jews and Arabs at the time, their myths and their ethos, their crises, their initiatives, their reactions to what was happening and what they thought might be happening. These are indispensable pieces of the mosaic that historians must strive to put together. No small number of praiseworthy, even great, studies have already been devoted to them. In the final analysis, however, these local stories have to fit into a larger picture that seeks to tell the story in its wider dimensions, or at least in terms of some of the reciprocal connections between the larger historical circles and the smaller ones.

The advantage of the outside-in historical approach is that it prioritizes the general picture without surrendering the more concrete local one. It neither bows to collective memory nor tries to erase it. In Israel, this is particularly important. It was precisely part of the larger Zionist project from the beginning to move Jewish self-understanding away from the sense that we must inevitably be “a people that dwells apart, unreckoned among the nations” (Num. 23:9).

Our argument is not that Yom HaAtzmaut ought to be celebrated differently or that collective memory must be jettisoned, but it is not purely academic either. When the history of the Yishuv and Israel is taught in Israeli schools and universities, its teachers ought not be afraid of the comparative dimension. The Yishuv and Israel must not be taught and understood from within the closed gates of an intellectual ghetto, as it were, shutting out the broad history of the Middle East, Europe, the United States, or the world in general.

Whether history is studied and taught according to (nonexistent) rules is not the issue here. But history understood from the outside in imparts a certain measure of modesty. It does so, moreover, without denying the uniqueness of Jewish or Israeli history. It might even lead us to a more balanced assessment of their intertwined futures.

Suggested Reading

Chaim of Arabia: The First Arab-Zionist Alliance

Chaim Weizmann regarded his 1919 agreement with Emir Faisal as an epoch-making treaty. That didn’t turn out to be the case, but a century later an Arab-Zionist alliance may be reemerging.

Shifting Sands

Shlomo Sand believes that nations are, in the nature of the case, modern inventions, and that Israel is a particularly bad one.

Missing Menachem

When Menachem Begin led the Likud to victory in 1977, Yitzhak Ben-Aharon spoke for many in the Israeli political establishment when he said that “if this is the will of the people, we have to replace the people.” Begin’s image has evolved, but he remains a contested figure.

A Sharp Word

From his intensive study of Hebrew and Jewish history to a surprisingly romantic Zionist congress in Basel, and the horrors of the Kishinev Pogrom, 1903 seems to have been a turning point for the young Jabotinsky.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In