Early Modern Blasphemy and Postmodern Virtue

In the mainstream of Jewish collective memory, Jacob Frank was portrayed as an egomaniac- al and depraved ignoramus, a false messiah, and a cynical serial convert—first to Islam, then Christianity. More recently, however, he has become the subject of radical reappraisal, most notably in Nobel Prize–winner Olga Tokarczuk’s novel The Books of Jacob, which depicts Frank as an eighteenth-century forerunner of a multicultural Poland and modern sexual liberation. Jay Michaelson makes a complementary theoretical argument in The Heresy of Jacob Frank, which received last year’s National Jewish Book Award for scholarship.

Both writers take their cues from the revisionist impulses that have been percolating at least since the scholarship of Gershom Scholem. Scholem described Frank as “truly corrupt and degenerate” but also saw him as heir to Shabbtai Zevi and his followers’ assault on rabbinic authority, which Scholem believed had laid the groundwork for Jewish modernity. But the immediate foundation for these revised views of Frank is the groundbreaking research of Pawel Maciejko, particularly his 2011 book, The Mixed Multitude, which set a new standard for evenhanded analysis of Frankism. Among other things, Macie-jko’s detailed reconstruction of the historical record demonstrated the extent to which Frank’s Jewish opponents bore responsibility in exacerbating his conflict with the rabbinic establishment.

Michaelson, well known as a popular writer on religion and spirituality and an activist for gay rights both in Jewish life and the broader world, has been studying Jacob Frank for almost two decades. In a recent essay, he described being “seduced” by the “allure” of Frank’s vigorous confrontation with traditional Jewish law and norms in The Words of the Lord, the late miscellany of Frank’s oral teachings and anecdotes. “As a queer person who remembers all too well the repressive restrictions of traditional religion,” Michaelson wrote, “I found Frank’s rejection of those restrictions to be inspiring.” He completed his PhD at Hebrew University in 2012 with a dissertation analyzing “materialism, sexuality and law” in The Words of the Lord and went on to publish an article called “Conceptualizing Jewish Antinomianism in the Teachings of Jacob Frank,” which argued that Frank’s self-conscious rejection of halakha was not fundamentally nihilistic. Rather, it was motivated by Frank’s “skeptical/humanistic” outlook, which led to the rejection of “valueless” and outmoded constraints on “human flourishing.” As Frank had argued:

All religions, all laws, all books of old, if one reads them, it’s like turning your face backwards and examining words which have long gone extinct. All this originated from the side of death.

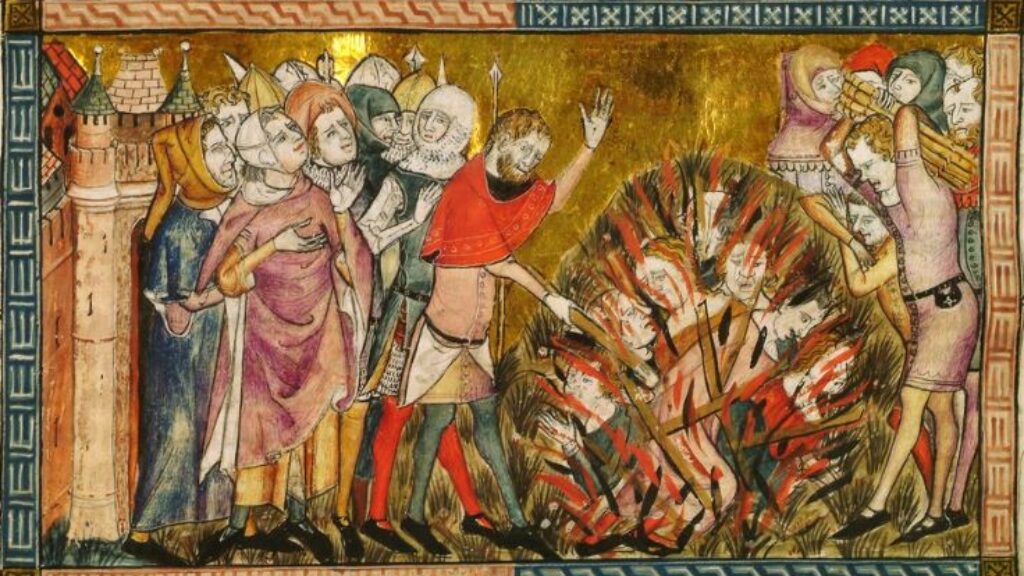

In the sprawling corpus of Frankist writings, Michaelson discovered a doctrinal core “worthy of attention as a religious phenomenon,” which he summarized as “a coherent, materialistic, and protomodern skeptical worldview . . . combined with myths and tales of startling originality.” “Startling” may, in fact, be too soft a description of a vulgar, syncretic creativity that encompasses, among other things, scatological humor, crude sexual boasts, a new divine pantheon, and magical gnomes. Michaelson’s reading also insulates Frankist thought from the historical events that were key to Frank’s villainization in Jewish collective memory: the disputations staged by Frank’s acolytes with their rabbinic adversaries under the auspices of the Catholic Church, which resulted in the burning of the Talmud and a blood libel.

In The Books of Jacob, Tokarczuk took the cocky and disjointed first-person narrative of The Words of the Lord at face value and rendered a fictional Jacob Frank who actually did most of the outrageous things he claimed to have done. Michaelson, in contrast, chooses to read The Words of the Lord as a deliberate self-fictionalization. “These are the actions of a constructed literary character,” he writes, “not records of history.” This approach shifts the focus from moral censure of Frank’s actions to analysis of his intentions as a storyteller. Following and furthering a Bakhtinian reading first proposed by his teacher Rachel Elior, Michaelson suggests that the bawdy and aggressive tales of The Words of the Lord enact a “carnival of the grotesque” in order to puncture received wisdom and unleash the libidinal forces held in check by puritanical tradition. He also argues, persuasively, that this places Frank in the company of other eighteenth-century charlatans, libertines, and esoterists, including Casanova, the Marquis de Sade, and the early Masonic orders.

Michaelson does succeed in conveying the “startling originality” of Frank as a provocateur, a sort of eighteenth-century Lenny Bruce, who, in what is likely the most notorious passage of the collection, said to his followers: “Having come to the synagogue in Salonica, I took the Law of Moses, put it on the ground, pulled down my pants, and I sat on it with my bare behind.” But, as he endeavors to bridge between the frisson of the early-modern page and the terms of present-day liberal virtue, Michaelson’s effort wears thin, largely under the pressure of the fleshly Jacob Frank himself. Over the course of the book, Michaelson increasingly indulges in a tendency to bake into his summaries conclusions he has only tendentiously established in argument. We are ultimately expected to assume Frank was a quasiscientific “rationalist” devoted to “skeptical materialism” and a protoqueer and protofeminist champion of “liberated sexuality,” even as evidence from text and history does not point so easily in these directions.

The case for skeptical materialism, for example, rests largely on holding Frank’s grossly materialistic scorn for pious theology purposefully distinct from the byzantine and self-serving occult gnosis he substituted for it. In justifying Frank’s expressions of disdain for prayer and ritual, Michaelson invokes the reasoned atheism of Enlightenment philosopher David Hume as well as post-Holocaust theodicy. He then seems almost surprised that Frank’s thought could simultaneously encompass a fantastical panoply of gnomes, demiurges, and magic ritual as well as a mythic quest for riches and immortality. Though Michaelson, fairly enough, reads this materialistic quest as further evidence of Frank’s favoring of matter over spirit, it also suggests that Frank was not so much a rationalist as the kind of alchemical speculator that emerged—and continues to emerge—in the twilight overlap between empirical science and magical thinking. Frank may have been less a Humean skeptic than a cynical manipulator who played upon the yearnings of weaker people for his own profit and glory.

Other dimensions of Michaelson’s presentation are similarly oversold. Although, in his religious boundary-crossing, Frank may have prefigured the eclectic universalism that Michaelson celebrates, it is not so easy to dismiss the claim that he acted out of sheer opportunism. When, after already having converted to Islam and Roman Catholicism, Frank abandoned his flirtation with Eastern Orthodoxy, it was because his overture to the tsar had failed.

Michaelson’s argument for Frank’s queerness amounts to a too-clever act of wish fulfillment: If the Sabbatean and rabbinic cultures out of which he emerged were characterized by a feminized manhood—as Daniel Boyarin and others have argued—then Frank’s priapic masculinity, which Michaelson elsewhere describes as “toxic,” was a “queering of the queer.” In the absence of further argument, this suggestion amounts to little more than patterned theoretical wrapping paper for a questionable historical package.

As for feminism, Michaelson pins his argument primarily on Frank’s incorporation of “the Maiden” into his divine pantheon. This figure embodied “sexuality and vitality as the doorway to worldly redemption and eternal life” and was associated by Frank with his daughter and successor Eva. He contrasted the Maiden with “the Unholy Mother,” who symbolized pious sexual repression. But calling this feminism rests on an underwhelming analysis of the use of female imagery in a phallic imagination. Michaelson makes much of dictum 397 of The Words of the Lord, in which Frank appears to demand an act of “sexual antinomianism” from his followers, so as to slip the clutches of the Mother and liberate the Maiden. Michaelson describes this as a “rejection of normative religion’s needless constraints on human flourishing” while also suggesting that it entailed the emancipation of real women. But this text is, in fact, misogynist in its attitude toward actual women (“For she is a woman,” Frank says, “and of lower degree than a male”). And the rather familiar drama of a man trying to wrestle his way out of a smothering maternal embrace, so as to lay claim to the willing houri, is no parable of women’s liberation. Although Michaelson would have us salvage from this vision an adumbration of African American lesbian feminist Audre Lorde’s notion of “the erotic as power,” it has more in common with Portnoy’s Complaint, which has seldom been confused for a feminist manifesto.

Michaelson does make an allowance for the likelihood that Frank’s scandalous reputation was not simply the result of slander. He writes:

None of this analysis is intended to somehow rescue Frank, who remains, based on the textual evidence available to us, a manipulative, violent, and cruel individual who extorted his followers for material gain.

Yet, despite this disavowal, his book attempts, if not a historical rescue, at least a tentative theoretical rehabilitation. Occasionally, it even veers into apologetics. For instance, Michaelson counters suggestions that Frank was motivated by simple hedonism with the argument that he could easily have followed his early rival Leib Krysa out of the movement to pursue his desires without theological trappings. But on this point Maciejko’s sober history is clear: Krysa left after he lost a power struggle to Frank, who stayed because he won. In any case, such an argument fails to account for the extent to which cult leaders like Frank are motivated less by pleasure than the will to dominate and financially exploit their followers.

Michaelson goes even further than Maciejko in describing reports of wild sexual activity among the Frankists as largely the figments of his rabbinic opponents’ prurient imaginations. Whatever little did happen, he argues, can be defended as “rigidly controlled” antinomian ritual, in the service of sensual freedom. But controlled by whom? It is, to say the least, unclear why such erotic ritual, which at heart still amounts to a dominant man dictating the couplings of his followers, possibly without their consent, is liberating, let alone ethically superior to ordinary hedonism.

Perhaps the most frustrating dimension to Michaelson’s effortful adumbration of Frank into contemporary figures like Lorde is the reality of how many far less savory modern personalities Frank more clearly resembles. One thinks of the Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh, for example, who, with his squadron of Rolls-Royces, managed to realize the Frankist fantasy of golden carriages and, on the basis of a syncretic philosophy, drew around himself a hypnotized community rife with sexual abuse and paramilitary fervor. But the more intriguing comparison is one that Michaelson actually acknowledges, in the briefest of parentheticals, in an essay I quoted above: Donald Trump. Beyond the comic resemblance—both had two ne’er-do-well sons and an idolized daughter—lies a remarkable shared profile: vulgar charisma, improvisational monologues, sexual braggadocio, venality, authoritarianism, compulsive flouting of norms, and rapt followers. If nothing else, this comparison should indicate the extent to which Michaelson’s presentation of Frank as a sex-positive prophet for our times is an act of willful interpretation.

Michaelson’s close readings do, however, transmit something of the “allure” of The Words of the Lord, which, at least in a curated version, does merit greater attention as a chapter in the legacy of Jewish thought and culture. Frank was clearly not the ignoramus his opponents depicted him to be but a kind of amoral savant, set at odds with authority by the turbulence of his own id and insatiable will to power.

It makes sense that those in our time who rightly view themselves as shackled by some of the same orthodoxies Frank challenged might be tempted to consider him a spiritual godfather. But such a rehabilitated Frank, though seemingly the diametrical opposite of the monster preserved in the annals of collective Jewish memory, is also an exercise in caricature. Eventually we must return to complex historical reality, in which the same figures who thrill us with sensations of release and fulfillment may also pave the road to enslavement and moral catastrophe.

Rather than reading Jacob Frank as a rough draft of liberation, it might have been more enlightening to analyze him as a case study in the seductive allure of bad people.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

Weird Big Brother

Jacob Frank and his bizarre religious movement still casts a strange spell over. Is Nobel Prize winner Olga Tokarczuk’s newly translated novel the War and Peace of Jewish-Polish heresy?

Secularism and Sabbateans

How did the Jews become modern? Three new books trace the roots of Jewish secularization.

Jews, Genes, and the Black Death

This is the version of history that many of us heard in Hebrew school: Jews were saved from the plague by handwashing, kashrut, and burying their dead quickly.

Remembering the Scholems

New books about Gershom Scholem and his brother Werner evoke memories of 28 Abarbanel Street in Jerusalem.

gershon hepner

THE BOOKS OF JACOB’S MESSIANIC MUDDLE

“Why is it that some people have to pay while other people can collect?”

is a question that is asked in Olga Tokarczuk’s book “The Books of Jacob,” featuring a false messiah who’s called Jacob

Frank, who frankly did not give a damn about what was religiously correct,

his program like that of all false messiahs a sad nightmare that provided no one with a call that led to any wake-up.

These calls are always over before they are really over,

directed never by a genuine Jehovah,

far less enjoyable while they happen than in retrospect,

when they turn into subjects that philosophers dissect.

Pedro Bilar

I had enjoyed reading "Rabbi" Weiner's book review on Jacob Frank's life and times until I saw that he couldn't hide his politically correct leftist bias by making a comparison between one of the most reviled figures in Jewish history and a former US President that had done more for Israel - and thus for the Jewish people - than almost any other in modern times.

Does the "Jewish Review of Books" have to include contributions by Jews in name only representing marginalized elements of "Jewish" life on their way to full assimilation?