From Turban to Top Hat

The fabulously wealthy Jewish grandees of yesteryear are currently en vogue. A slew of recent publications, exhibitions, and research ventures, such as the United Kingdom’s Jewish Country Houses Project, has brought the perfumed lives of the Ephrussis and the Camondos, the Rothschilds and the Sassoons back into the public eye, affecting the ways we ordinary mortals think about pedigree, legacy, the fate of precious objects, and the weight of history.

In what might be called “The Year of the Sassoons,” the past twelve months witnessed, in quick succession and by happy coincidence, the release of Benediction, a film about the poet Siegfried Sassoon; the publication of Joseph Sassoon’s magisterial work, The Sassoons: The Great Global Merchants and the Making of an Empire, which attributes his ancestors’ financial success to their adaptability as immigrants; Sotheby’s exuberantly promoted auction of the Codex Sassoon, the earliest most complete Hebrew Bible in book form, which sold for $38 million this spring (though by then it was no longer in the family); and a sweeping exhibition at New York’s Jewish Museum, accompanied by a sumptuous, gilt-edged catalog, both of which are called, simply, The Sassoons, as if they required no explanatory subtitle.

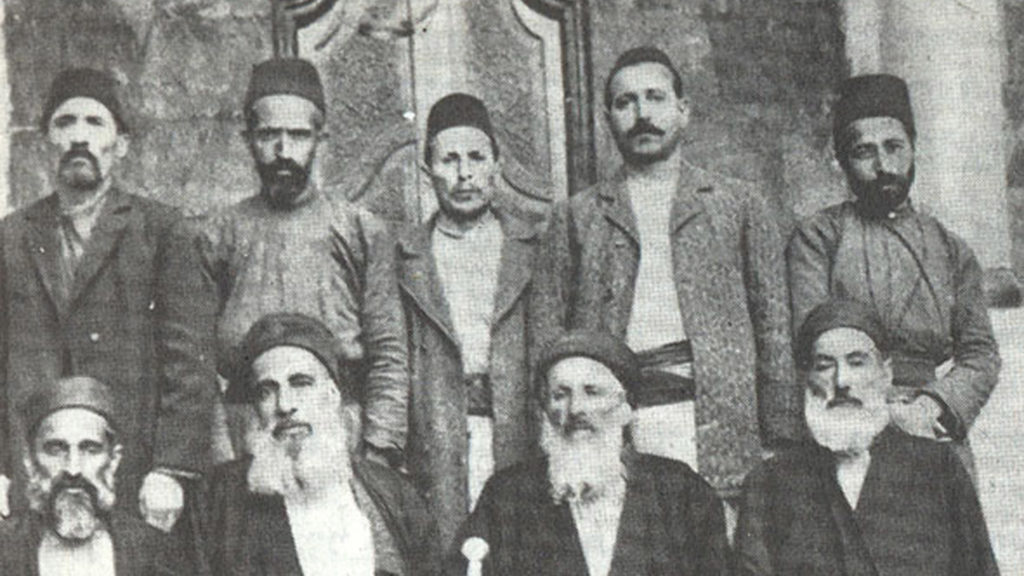

The very model of a mobile, transnational Jewish family of the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries with roots in Baghdad and ties to Bombay, Hong Kong, Shanghai, and London—where they set up shop and sanctuary—the Sassoons lived a gilded life, one sustained by global traffic in cotton, pearls, oil, and opium. Awash in grand things, housed in equally grand country homes such as Port Lympne, the stylistically eclectic, fancifully decorated Kent residence of Sir Philip Sassoon, a baronet and a member of Parliament, as was his father before him, the Sassoons were equally awash in good deeds, in splendid acts of civic and Jewish communal philanthropy.

Like other grandees of that imperial era, successive generations of Sassoons not only hobnobbed with pashas, princes, prime ministers, and the members of the British royal family, they also made collecting—that exercise in trophy gathering and self-assertion—one of their hallmarks. Nearly every member of the family collected something. Some Sassoons gathered Chinese porcelains and ivories. Under a separate roof, other members of the family assembled rare Hebrew manuscripts and elaborate Jewish ritual objects. And still others trained their sights on and filled their homes with paintings by Gainsborough and commissioned portraits by John Singer Sargent, in his day the preeminent painter of the beau monde.

With so many treasures from which to choose, it’s no wonder that the making of The Sassoons took its co-curators, Esther da Costa Meyer and Claudia J. Nahson, far and wide: to London and Cambridge, Paris and Barcelona, Pune and Mumbai, where they visited the Sassoon textile mills and attended Shabbat services at the recently restored Keneseth Eliyahoo Synagogue, which, in the 1880s, Jacob Sassoon had built and named in honor of his father, Eliyahoo (Elias in English).

Along the way, they collected marvelous objects from members of the multiple branches of the Sassoon family as well as from the British Museum, the Victoria and Albert Museum, and the National Trust. His Majesty, King Charles III, loaned several items too. His great-grandmother, Queen Mary, had received, among other things, a Cartier desk clock fashioned out of lapis lazuli and mother of pearl and a perfume flask made of jade and glistening with diamonds, emeralds, and rubies as birthday presents from Sir Philip.

No sooner do you enter the world of The Sassoons, which takes up the entire second floor of the Fifth Avenue museum, than you’re greeted by a portrait of David Sassoon, the father of fourteen children by two different wives. Painted by William Melville, a British expat living in India, David Sassoon is the very image of a nabob: turbaned, robed in silk, and sporting a diamond ring on one pinky and a ruby ring on the other.

Before long, visitors happen upon yet another portrait of a male Sassoon, one painted by Sargent: that of Sir Philip, David’s great-grandson, who, dressed to the nines, is the very model of a British aristo of the 1920s. The contrast between the two Sassoons underscores what Cecil Roth, in his spirited 1941 account of the family, characterized as its “amazing metamorphosis . . . from Baghdad to Windsor . . . from the turban . . . to the top-hat.”

Marveling at their rapid transformation, the British historian put it this way: “What family could have been less English in its tastes a century ago? What family has produced members who are more so to-day?” Others, less charitably, were more inclined to speak darkly of their wholesale makeover from “Asiatic” Jews into cosmopolitan British ones. As Siegfried Sassoon once cleverly, if waspishly, described his family, the Sassoons were “Semitic sovereigns.”

Several of the Sassoon women—Rachel Sassoon Beer, Aline Rothschild Sassoon, and Sybil Sassoon, later the Marchioness of Cholmondeley—also loom large in the galleries of the Jewish Museum. Painted by Sargent, they, too, are dressed beautifully, swathed in yards of silk, but here the fabric conveys confidence rather than exoticism. No veiled creatures they, Sargent’s Sassoon women stand tall, as befits their key roles in promoting the family’s good name through their business acumen, social conscience, exquisite taste, and faithfulness.

Elsewhere, in beautifully proportioned glass vitrines that float on platforms in the middle of the galleries, one precious Hebrew manuscript after another—a fourteenth-century edition of Maimonides’s Guide for the Perplexed, a Karaite liturgical text from the Cairo Geniza—holds court. My eye was drawn to an astronomical anthology (circa 1361) from Catalonia, whose depictions of the heavens, rendered in ink and paint on parchment, are colorful, even playful. Once the proud possessions of David Solomon Sassoon, who in the twentieth century assembled the world’s greatest private collection of Hebrew manuscripts, these rarities are now dispersed among the holdings of the British Library, Cambridge University, the Jewish Theological Seminary, and the University of Pennsylvania.

Other vitrines showcase majestic silver gilt and enamel Torah and haftarah cases created in Iraq and China and commissioned by Flora Sassoon, who in the late 1890s managed the Bombay office of David Sassoon & Co. after her husband’s death. A pair of dainty Torah finials, made in England in the early 1800s, keeps the Torah cases company. Topped by tiny pineapples wrought in silver, these ritual objects are ornamented by a suite of little bells that appear to cavort in space. They rang in the news that Jewish ritual objects could please the eye as well as honor tradition (though for the Sassoons, it was always more about the eye).

And there’s more: a thirteenth-century Chinese scroll, whose delicately rendered pear blossoms tug at the heart, is unfurled in all its glory; an assemblage of famille verte, vivid green porcelains intended to hug a mantelpiece, lights up the gallery in which it temporarily resides.

The exhibition concludes with a poignant array of materials belonging to Siegfried Sassoon, including the pocket-sized World War I notepads in which his doodles and poems first appeared. The Sassoons then swiftly advances onto World War II, where it acknowledges Victor Sassoon’s wartime work on behalf of Jewish refugees stranded in Shanghai and Bombay. And with that grim reminder of the fragility of all things, this display comes to a stark close, as did India under the Raj and pre-Communist China, two lands in which various Sassoons had once, but no longer, flourished.

With its emphasis on family and its commitment to bringing together what had once lived apart, The Sassoons might be considered a pendant to last year’s The Hare with Amber Eyes, a moving, enveloping show about the Ephrussis that was also mounted at the Jewish Museum. In other respects, though, the two displays couldn’t be more different. Where Hare’s installation was as much a framing device as a physical container and wore its heart on its sleeve, the contents of The Sassoons are housed in a far more straightforward, traditional format whose tone is subdued, even neutral, and whose objects pretty much fend for themselves. Are we meant to ooh and aah at the family’s good fortune or sigh at the vagaries of fate? It’s left to the viewer to divine the deeper connections between the Judaica and the Sargents, the books and the chinoiserie, to figure out what this admittedly stunning assemblage of object adds up to beyond a testament to the Sassoons’ discernment, or its lucre.

This viewer, for one, needed a helping hand. For that, happily, there’s the catalog, itself a work of art. Its beautifully appointed pages make explicit what otherwise remains allusive, muted: the Sassoons’ relationship to the material world. A trio of richly researched essays by the curators on objects, art, and architecture round out our understanding of that relationship. “The buildings they erected, the homes in which they lived, and the objects they collected and cherished all contribute to this narrative,” Nahson and da Costa Meyer explain, cautioning against reducing tales of the peripatetic Sassoons to an “allegory of the modern condition.”

Ultimately, though, The Sassoons has to succeed on its own terms—as an integrated visual experience with a point of view—which brings me back to the second floor of the Jewish Museum. There’s so much to take in and absorb that I came back for another look. This time around, I found what for me was the key: the exhibition’s palette. Paralleling and subtly reflecting the family’s migration from East to West, the color of the walls in each gallery shifts from vibrant, saturated hues of violet and burgundy to quieter, etiolated shades of pearlized gray and of ocher mixed with raw sienna as the exhibition unspools, following the family’s trajectory over time and space.

It may well be that I’m reading too much into the exhibition’s color scheme. Perhaps the only objective of the show’s talented designers, Leslie Gill and Adam Johnston, was to make the Sassoon treasures shine, which they certainly do. Fair enough. But I’d also like to think that what’s at play here is a visual comment on the Sassoon family’s de-Orientalization. Though that old-fashioned, ten-dollar word appears nowhere in the exhibition—it prefers to speak of exile and assimilation, globalization and diaspora—the desaturation of Jewishness haunts the Fifth Avenue milieu of The Sassoons, much as it did the many places they once called home.

Suggested Reading

Crazy Rich Sephardim

For a time, Shanghai soared along with these unusual Ottoman Jewish émigrés, the Sassoons and the Kadoories.

A Tale of Two Exiles

What did a seditious Sicilian duchess and the heretical son of a chief rabbi have to do with the beginnings of French antisemitism?

History with a Flourish

So much gets lost in translation—and to history—when household items, heavy with use, first assume the status of heirlooms and then land in museum vitrines, heralded as art rather than history.

That in Aleppo Once

Does the most accurate biblical text belong in the synagogue, or in a museum?

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In