Lovers (and Haters) of Zion

The title of Derek J. Penslar’s new book, Zionism: An Emotional State, seemed timely enough when it first appeared early last summer. The hundreds of thousands of Israeli citizens who then rallied every Saturday night against their government’s ongoing attempts to institute judicial reform were mainly peaceful, but they were intensely emotional. Through their speeches, slogans emblazoned on signs and clothing, and songs, often accompanied by the rhythmic beating of drums and noisemakers, the demonstrators regularly revealed the depth of their passions—which evoked similarly strong feelings on the part of their adversaries, both in the government and outside it.

And then, on Simchat Torah, October 7, 2023, Hamas unleashed the most horrific attack in Israeli history on the border towns and kibbutzim of southern Israel. No reader of this magazine, no one in Israel, indeed no Jew anywhere has been untouched by these recent events or has failed at least to witness and most likely to feel powerful emotions about what is going on in and around Zion.

The sheer scale of the horror was unprecedented, but for a century and a half, the Zionist project to resettle Jews in their homeland has aroused emotional responses and impassioned debates among Jews and non-Jews everywhere. Fully aware of the nature of these debates, and fully conversant with the vast scholarly literature concerning them, Penslar, a distinguished professor of Jewish history at Harvard, has chosen not to write yet another book analyzing these debates but to strike out in a different direction and focus less on their substance than on the emotions underlying them.

Writing that “the energy propelling the Zionist project comes from a series of emotional states,” Penslar sets out to examine and compare and contrast them. He also discusses the emotional states of those who not only reject Zionism but hate it.

Penslar begins with nineteenth-century proto-Zionists and the early self-described Lovers of Zion (Hovevei Zion), mapping out the different forms of love and attraction to Zion as well as other feelings that have developed in the Zionist world and outside it over the ensuing years up to the present.

After noting that “standard accounts of Zionism usually juxtapose the approach of the Hovevei Tsion with that of Theodor Herzl,” he observes that the two were actually “very similar on the emotional level.” Men like Leon Pinsker, “no less than Herzl, saw in Zionism a means for Jews to overcome the shame of passivity and to restore their honor by becoming masters of their own fate.” Turning to the pioneers of the second aliyah, Penslar echoes Boaz Neumann’s recent evocative description of their “both sexual and chaste” love for the Land of Israel, highlighting the fact that it was shared by men and women alike.

Penslar is not just telling a love story though. He is attentive to tragic dimensions of Zionism, the plight of those whose love of the land was unrequited, who were the victims of self-doubt, isolation, and malaria, some of whom “gave vent to their despair by engaging in occult practices, and their tombstones at the Kinneret cemetery bear mysterious satanic symbols.”

But this is only the beginning. Penslar goes on to reflect, among other things, on the “interethnic conviviality” that characterized some Jewish-Arab interrelationships until the 1930s as well as “powerful negative emotions toward Arabs” in the aftermath of later violence and “the trauma wrought by the Holocaust” on the Jews of Palestine. When he turns to the period of the actual establishment of the state, he shares with his readers the results of a little-known series of public opinion surveys undertaken by the Haganah in Haifa in the winter of 1948:

The surveys revealed that the Jewish civilian population’s emotional state ranged from grim to optimistic, but that for the most part they were resolute, calm, and willing to endure substantial material sacrifice for the war effort. Their main fear was of civil war between the Haganah and the Irgun; primary sources of frustration were profiteering and an unequal distribution of wartime obligations among Jews.

A great deal of Penslar’s attention is devoted to what has taken place beyond the Middle East and after Israel achieved its independence. He systematically explores the emotional sources of the different sorts of solidarity that diaspora Jews, especially American Jews, have felt with the Zionist enterprise and the way in which their orientations have changed over the years, particularly since 1948. “The emotional intensity of American Zionism increased immeasurably in the wake of the Holocaust,” he explains, “which left American Jews grieving for lost loved ones, anxious for the surviving remnants of European Jewry, and burdened by survivor guilt.” The engagement of most American Jews with Zionism was, then, different from “the sentimental and romantic love” felt by the late-nineteenth-century Lovers of Zion or the twentieth-century Labor Zionist pioneers, yet “these affective bundles” of different people “shared much in common, including a striving for honor and for respect among the nations of the world.”

In short order, the Jews of the diaspora, American Jews foremost among them, did become romantically involved with Israel:

American Jews were both proud and in awe of Israel’s fortitude and valor—feelings that David Ben-Gurion knew how to exploit when he journeyed to the United States in May 1951, bringing with him two Israeli naval vessels and a bevy of female IDF soldiers, to launch the first Israel Bonds drive.

American Jews could then buy a piece of the action. For the right sum, you could become a “Guardian of Israel” and thereby “experience not only vicarious pride in Israel’s accomplishments but also a personal sense of empowerment.”

Penslar, like many other recent authors, ascribes a great deal of importance to the role played by Leon Uris’s 1958 novel Exodus in spurring the American romance with Israel, but he does not, like most of them, mistake its appearance for a great turning point. “In fact,” he correctly writes, “the novel did not create so much as reflect and articulate pre-existing sensibilities—otherwise American Jews would not have found the book appealing.”

Penslar does see the Six-Day War, however, as a turning point, one that “elicited a flood of American Jewish support for Israel unseen since 1948.” He accurately surveys many of the effects of the war on American Jewish life, though he sometimes goes too far, seeming to suggest that it gave birth to summer camps promoting the love of Israel through song, dance, and Israeli counselors, when, in truth, the summer camps came first.

Penslar also charts the much-discussed evidence of a recent decline in American Jewish support for Israel among younger people. He cites but does not really endorse journalist Peter Beinart’s claim that this can be traced to the clash between their progressive values and the oppression of the Palestinians. On the other hand, he sees flaws in sociologist Theodore Sasson’s supposition that these young people will, like their parents, “gravitate to Israel as they mature,” though he does admit that Sasson’s view is bolstered by the success of the Birthright program.

Penslar takes note of a number of left-wing American Jewish intellectuals, some of them quite prominent, whose disgust with Zionism’s results has led them to oppose it vocally and publicly. But they are not, he insists, representative of the American Jewish community as a whole, even if its members’ love for Israel is not what it once was. “Most early twenty-first century American Jews,” he writes, “were not overwhelmed by guilt, shame, disappointment or embarrassment about Israel. They were, if not fervently Zionist, ‘Zionish,’ as my college-age daughter once described her own feelings about Israel.” This may sound rather lukewarm, but it now typifies even communal “activists who champion robust attachments to Israel.” Such activists acknowledge “the need to exchange naive idealism for a new realism, a ‘mature love’ different from the erotic Zionist ardor that had surged through the Jewish community from the 1960s until the turn of the millennium.”

Rich and variegated as Penslar’s treatment of the “emotional state” of Zionism undoubtedly is, there are many bases that one is surprised not to see him touch, including the most emotionally evocative document in the Zionist library today. I don’t mean the Balfour Declaration, to which he makes dozens of references, but Israel’s Declaration of Independence. Formulated at a highly emotional moment in May 1948, it includes a concise summary of previous justifications for Zionism and continues today to serve as a point of departure for many theoretical discussions of Zionist ideology. In the mass protests that took place last year, people declared themselves ne-emanim, or “faithful,” to it. One of my neighbors in my town in the Negev still displays a huge banner on his fence with just the word “ne-emanim,” and that alone conveys to everyone exactly what he means to say. The Declaration of Independence, now more than ever, excites the passions of Israelis and is celebrated by them in a way that should have led to consideration of it in a book like Penslar’s (though, admittedly, the events that have most strongly underlined its salience occurred after his book was, in all likelihood, almost finished).

Already at the beginning of his book, even before he zeros in on his main subject, Penslar addresses the question of “Zionism and colonialism.” He is aware that Israel’s most vehement critics today, both Jewish and non-Jewish, regard it as a living relic of the age of colonialism, guilty of denying the rights of an indigenous people, ethnic cleansing, imperialism, racism, and apartheid. Penslar summarizes both the cruder and the more sophisticated versions of these “associations between Zionism and colonialism” but fails to give due attention to certain Zionists who denied them decades ago, such as Jacqueline Kahanoff, whose Middle Eastern background often leads to her omission from studies undertaken from an American or European perspective. Penslar mentions her in passing but does not identify her as a proponent already in Israel’s early years of a Zionism infused with a pluralist, multicultural Levantism.

Born in Egypt to a family with Iraqi and Tunisian origins, Kahanoff initially settled in Beersheva, a modest and raw frontier town that in the 1950s was absorbing many new immigrants from the Arab Middle East. She saw these people as local, as indigenous and belonging to the land, and to which they “had returned by right and with justice.”

Penslar himself does not take sides on this issue, though he argued in his first book, Zionism and Technology, published in 1991, that early Zionist settlement officials, who were often central European Jews, may have been influenced by the German strategy of establishing a minority population through small settlements in Poland to gain mastery of the surrounding territory. Thirty years later, he now has some new and highly nuanced thoughts about the relationship of Zionism to colonialism, but it is not completely clear why he chooses to devote a whole chapter to expressing them here before addressing “the emotional turn to Zionism.” He claims that he is doing so to set the stage for what is to follow, but it is difficult to see how, except insofar as his analysis foreshadows the notion that Israel may be considered to be an oppressive intruder in the Middle East.

The last chapter of the book, “Hating Zionism,” is where this theme really comes to the fore. It bears a somewhat misleading title, since it deals not only with hatred directed against Zionism but also with the ways in which Zionism has itself been a “generator of hatred.” This reflects its author’s conviction that an understanding of the ways in which “Zionism encourages hatred” of Arabs “throws new light on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, particularly over the past twenty years, when violent acts by Israeli Jews toward Palestinians became more common and socially acceptable.” What Penslar doesn’t do, however, either in this chapter or anywhere else in his book, is explore the deeper theological sources of Jew hatred that underlie the most ferocious animosity toward Zionism, the kind that we have just seen explode so viciously.

As Hamas’s barbaric attacks unmistakably demonstrated in October, would-be destroyers of Israel may espouse up-to-date theoretical denunciations of Israel, and their vicious acts may be defended on that basis, but at bottom, their hatred of it is due to their absolute rejection of the Jews’ claim to sovereignty. Their religion, as they interpret it, requires Jews to live as dhimmis—usually tolerated but always meriting discrimination and never entitled to independence and equality in what they regard as the dar al Islam (Abode of Islam). Justifying themselves through reference to the faith-based Hamas charter, which reiterates these views, the killers systematically butchered innocent civilians because they were Jews.

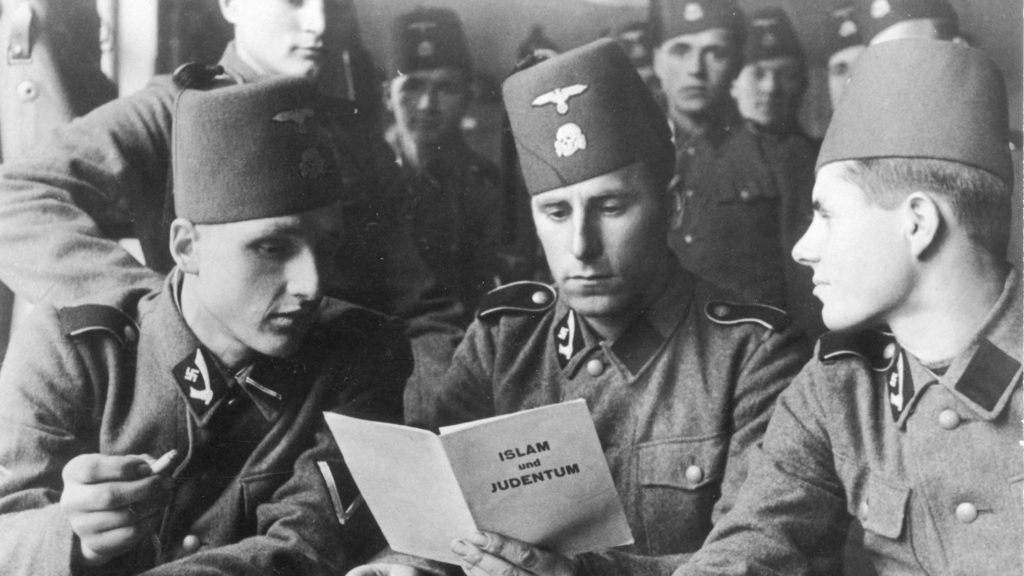

Islam, of course, does not always lead to hatred and brutality. Each of the Abrahamic religions contains many strands; each is capable of supporting diverse and contrary emotions. Rapprochement between Israel and Muslim states in North Africa and the Middle East is—or has been—taking place. But radical change takes time. Historic beliefs and tropes continue to find expression and shape behavior in ways that don’t necessarily have anything to do with what the Jewish state may or may not do. If one wants to provide a full explanation for the hatred of Zionism and Israel, the role of Islam, from the Mufti of Jerusalem to the murderers of Sadat to today’s headlines, religion cannot be left out of the picture.

In Zionism: An Emotional State, Derek Penslar has many insightful things to say about the complex tangle of beliefs and feelings that underlie the Jewish determination to return to the Promised Land, the support for it around the world, and the resistance to it, especially in the Middle East. While he touches on this last subject, he does not, however, truly plumb its depths. This would require a companion volume on the emotional state of anti-Zionism, one that digs deeply into its Islamist background. Penslar may not be the best person to write that book, but his pioneering project indicates just how significant it could be.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

Climate of Opinion

Academic scholars, of all people, should recognize that excoriation is not an acceptable substitute for argument, but, in fact, it pervades much of the discourse that today passes as “criticism of Israel.”

The First Lady of Zionism

At the age when most of us are just about to fold our tents, Henrietta Szold, pitched hers—and in the Holy Land, no less.

The Anti-Imperialism of Idiots

While it is customary to trace the Left’s bitter divorce from Israel to the Six-Day War of 1967, Susie Linfield shows that in some cases the relationship breakdown began earlier, in the late 1950s, when the New Left, having given up faith in the Soviet Union, decided anticolonialism is socialism,

The Hands of Others

Many people know of Mufti al-Husseini's SS activities. But how many Arabs shared his admiration for Hitler and attraction to Nazism?

Richard Landes

is there any discussion of various kinds of messianic hopes? hard to think of a more emotional issue.