Her Own Creation and Pure Luck

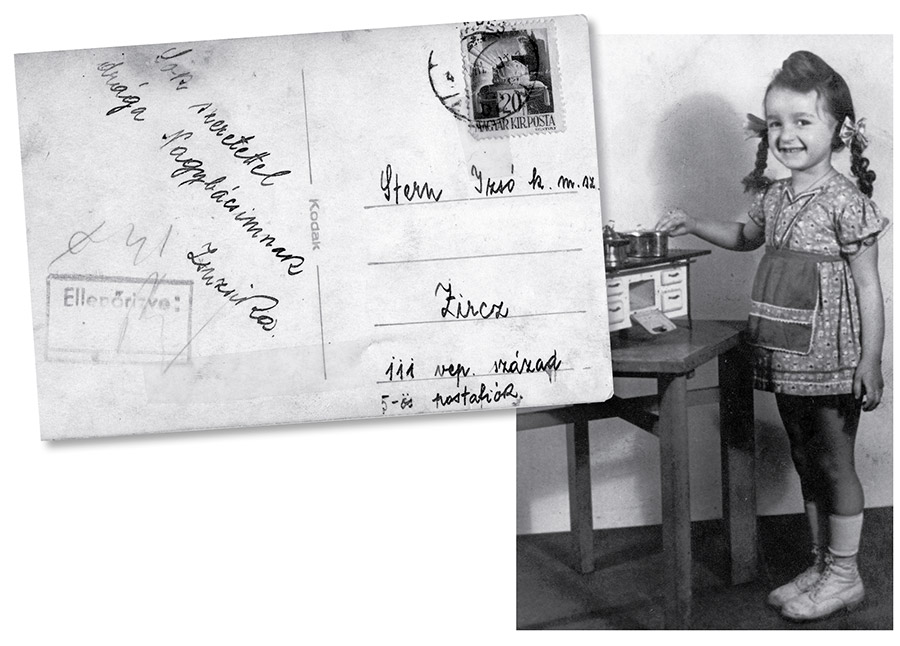

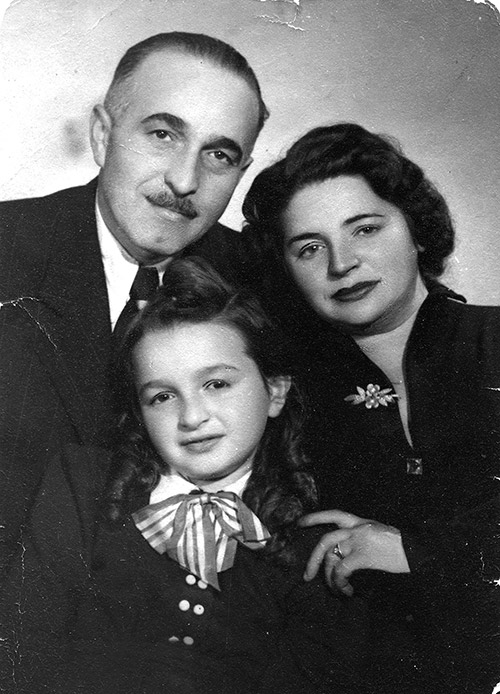

When Zsuzsika Rubin was four years old, her mother, Lilly, took her to a photographer’s portrait studio, where she wore different outfits and hairstyles and struck poses with props: as an all-grown-up lady doing her “daily shopping” with a plush dog and a straw basket, as a housewife in an apron hovering over a little toy stove. The two shots became postcards, one sent to Lilly’s sister Magda in France, another to her brother Izsó, who was in a forced-labor camp in Zircz in northwestern Hungary. The postcard to Izsó is undated, but the one to Magda—who had not yet met her niece—is dated February 14, 1944. Zsuzsika’s father was at a forced-labor camp himself, in Russia, though he returned home to Budapest five days before Lilly sent the postcard to her sister.

“To my sweet good Magduska, with much love and many kisses from little Zsuzsika,” wrote Lilly in Hungarian. “With much love to my dear uncle,” she wrote to her brother, signing it as Zsuzsika. A lifetime later, Zsuzsika, now Susan Rubin Suleiman, a professor emerita of French and comparative literature at Harvard, notes that the photography studio from her session as a little girl was called Mosoly Albuma, Album of Smiles. “At least some people were still smiling in Budapest in February 1944,” she writes in her new memoir.

Germany invaded Hungary the following month, to ensure the country didn’t desert its by-then tenuous alliance, and—Suleiman’s dry wit continues—to “take care, at last, of the Hungarian Jews,” the last Jewish community in Europe. Between spring of 1944 and liberation by the Soviet army a year later, more than half a million Hungarian Jews were killed. The Jews of Budapest, like the Rubins, lived in relative safety until the fall of 1944, when Hungarian’s fascist and passionately antisemitic Arrow Cross Party (Nyilaskeresztes Párt) came to power. In February 1944, while young Zsuzsika was sweetly posing for a photographer, Hungarian Jewry was on the brink of terror and death.

Suleiman has said she drafted Daughter of History during the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic “at a time when there seemed to be nowhere else to go but inward,” and she uses mementos like the surreally cheery photo postcards to dive into her childhood in Hungary and her young adult years in America. Her first chapter is titled “Postcard to Zircz,” and each subsequent chapter is likewise framed around an object. Suleiman describes how, in needing to stay put during the early pandemic, she was drawn to her “relics,” ordinary items infused with an emotional charge. “Some are not even material,” Suleiman adds, “but exist only in my memory: a fraternity pin I wore for a few months in college, a recording of Heifetz playing the Beethoven violin concerto.” The meaning of relic occasionally gets stretched past recognition, but Suleiman’s conceit works, particularly in the first half when they point to her early years and then emigration from Budapest.

Looking at the photo postcard sent to her uncle Izsó, who died at some point during the war though the family never found out where or when, Suleiman’s curiosity and dark humor illuminate her prose; she zigzags between poignancy and, somehow, moments of playfulness. Wondering how the postcard ended up with her mother, Suleiman considers a few possibilities:

Maybe it came back with a package of my uncle’s effects after his death? No, that would have been too civilized—and besides, there was never any official notification of his death. Maybe, when he saw that he was dying, he gave the photo to someone along with other papers and asked him to return it to the family. . . . I imagine the scene: 1945, summer or early autumn, my grandmother is still waiting for her son. A man knocks on the door, stands in the doorway, looking uncomfortable, shifting from foot to foot: “I brought you this, Izsó asked me to.” No, that’s melodrama. I don’t know how the photo got back to us.

In the first of three parts of Daughter of History, titled simply “Budapest,” Suleiman is a discursive yet deft guide, moving Zsuzsika Rubin’s story forward while exploring her swirling memories along with Jewish Hungarian history; she is, after all, a “scholar of war and memory.” Navigating past and present, scenes emerge in pieces: playing in the dirt, as a five-year-old, for weeks on a countryside farm with a Christian family until her mother was able to come for her; her family living, under false papers, at a noblewoman’s estate in Buda, where her parents worked as caretakers and Zsuzsika became Mary, learning in secret from her mother how to sing “O Holy Night” on Christmas; being liberated by Russians (who also jovially take her father’s gold watch from his wrist) and experiencing a brief respite, a time when “the Communist Party crackdown was only a glimmer on the horizon.”

Now in her mideighties, Suleiman could be forgiven for any emotional distance between her perspective today and her recollection of her earliest memories and feelings, but to the contrary, her point of view as Zsuzsika during her first, formative decade is poignant and clear. Suleiman then nimbly weaves in her current point of view. She writes of her return with her parents, in the spring of 1945, from Buda to their home in Pest:

We walked back to our house, crossing the Danube on a makeshift bridge. All the real bridges had been bombed by the retreating Germans. Walking between my parents, holding each one’s hand, I felt madly lucky and absolutely victorious, as if our survival had been wholly our doing and at the same time due entirely to chance. I was not aware of the paradox then, or if I was aware of it, could not have expressed it. But as I grow old, it occurs to me that I have often felt that way about my life: seeing it, for better or worse, as my own creation, and at the same time, contradictorily, as the product of pure luck.

Suleiman’s immediate family was certainly lucky. She survived, her parents survived, even her beloved Granny survived. And though her uncle Izsó died, her uncle Laci showed up at their door a few weeks after the rest of her family did. “‘I made it,’ he announced with a broad grin, his face grimy above the tattered jacket.” But the concept of having survived was complicated for Suleiman for a long time: “I was just a small child during the war, and except for the time on the farm, my little world had remained intact—that’s what I would have said, if anyone had asked me.” She knows that the experience of surviving is not always shot through with constant suffering, yet she recognizes that her story, too, is one of survival. This is not unlike the tension she feels between a life that is her own creation and one that is determined by pure luck.

In 1950 postwar Vienna, her family struggles to determine their next step, including the possibility of going to a DP camp. While discussing their family’s situation in contrast to the thousands of Jews who had survived the concentration camps and were now in DP camps, Zsuzsika asks her father:

We had never been to a concentration camp—were we displaced persons? Well, he said, we had had to hide from the Nazis and were persecuted during the war, so no wonder we had chosen to leave the country—that made us displaced persons. Yes, but didn’t we do that to get away from the communists? That too, he replied.

In fact, the same questions tormented my parents as well. Did we really belong in a DP camp, with all those unfortunate people . . . who had lost their whole families? . . . We had even flourished in the years right after the war, so why call ourselves displaced persons? But why not? We had left everything behind, hadn’t we?

Did the Rubins “belong” in a DP camp? The correct answer was yes, no, sort of.

They ultimately traveled next to Haiti before immigrating to New York, now as a family of four. In Haiti, Lilly Rubin, after several miscarriages in Hungary as well as losing a son after one day, gave birth to a baby girl. Judy was only a few weeks old when the Rubins arrived in the United States. Zsuzsika, soon to be Susan, was eleven.

The fraught project, for Suleiman, of becoming an American pulses through the second half of Daughter of History, intertwined with the similarly fraught project of becoming an adult; she details friendships and dates, high school in Chicago, college and a near-engagement in Manhattan. As a teenager, she was ambivalent about her traditional upbringing—something that was always most important because it was important to her father—and actively antagonistic toward her mother.

“I had a whole list of grievances against her: she didn’t read, she made me babysit for hours while she went shopping, she didn’t keep the house neat, she often yelled,” Suleiman recalls in the chapter “Seventeen” (as in the magazine). Her mother would berate Susan about her hair, her weight, the fact that she read too much. “In my eyes, Mother and I were enemies.” Yet Suleiman layers in a gentler point:

I think what I really held against my mother was that she could not help me navigate the storms of adolescence. My storms were exacerbated by all the baggage of my childhood—the war, the emigration, the multiple displacements—but in some ways they were just ordinary teenage dramas that my parents were not well enough equipped to handle.

That gentle understanding comes from Suleiman of today, not Susan Rubin of the 1950s, and it is from this distance that Suleiman recalibrates her adolescent image of her mother as “narrow-minded, unintelligent even” with “she was not an intellectual . . . but she was smart and plucky and had survived horrible losses by never looking back.” Suleiman does the looking back instead, seeing how her mother’s own young adulthood impacted hers: “[Mother] and her younger sister were beautiful girls without a dowry, not a situation with brilliant marriage prospects in those days. No wonder she worried about my hair!”

In fact, Lilly’s marriage to Moshe Rubin—she preferred to call him by his Hungarian name, Miklós, and in America he became Michael—was both a resolution of the problem of her marital prospects and itself a storm. Moshe Rubin came from an observant family. He had studied at a Hungarian yeshiva, received smicha, and then made a sudden, scandalous (at least for his father) left turn by marrying the beautiful, headstrong, culture-loving Lilly.

Suleiman, deeply interested in “history as a form of luck,” is just as interested in life shaped by action: “By falling in love with Lilly, my father revealed (or chose) a doubleness in his person and his loyalties.” Suleiman believes her father was both “a soulful Talmudic scholar” and a “bon vivant,” and though her family kept a baseline traditional observance, they were not part of an Orthodox community.

One day, while Susan was studying at Barnard, her father came in from Chicago to attend an Orthodox wedding in Brooklyn and asked her to go with him. After the wedding ceremony, men and women split into two different rooms to dance. All the men were dressed in black suits except for her father, who wore gray. She catches her father’s eye through the open door between the two rooms:

He was moving with the others, slowly, but his face had a quizzical smile as he looked at me, as if to say I appear slightly out of place, don’t I? Yet I know these people, I could have been one of them. As it is, I am a visitor. Maybe I am imagining that is what he meant. I do know that he never felt fully at peace, in one place or the other.

Michael Rubin may not have felt like he completely belonged anywhere, but, a generation later, Susan Rubin Suleiman has managed to find peace in belonging yet not belonging to several places at the same time. In her final chapter, “Round-Trip Tickets,” Suleiman considers her relationship to Europe, to Paris, to Budapest, and to one other place close to her heart.

“And America? How could I not love it too?” she writes. “I would be lying if I said I feel fully American—but why should we be fully anything? Incompleteness is the human lot.”

Suggested Reading

“A Story of Commitment, Solidarity, Love Even”

Retracing her father’s wartime journey from Poland, across the USSR, through Iran and eventually to Palestine, Michal Dekel learns a lot about what it means to belong to a people.

Singing Gentile Songs: A Ladino Memoir by Sa’adi Besalel a-Levi

Sa'adi Besalel a-Levi's memoir of life in 19th-century Salonica provides a rare and intimate glimpse into a lost Ottoman Jewish world. Sa'adi was an accomplished singer and composer and a printer who helped to found modern Ladino print culture. He was also a rebel who accused the leaders of the Jewish community of being corrupt, abusive, and fanatical. In response, they excommunicated him—frequently, capriciously, and, in the end, definitively—though with imperfect success.

It Was Like This: Excerpts from an Academic Memoir

Scenes from Anita Shapira’s gripping memoir.

Where To: America or Palestine? Simon Dubnov’s Memoir of Emigration Debates in Tsarist Russia

Dubnov's magisterial autobiography, written while Dubnov was in exile from both the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany, takes the reader on a deeply personal journey through nearly a century of upheaval for the Jews of Eastern Europe. A new translation.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In