Smitten with Sympathy

Although the Rabbis of the Talmud taught that we do unusual things during the Passover Seder to get children to ask questions, they didn’t think we should do them so that adults could give the wrong answers. And yet. Two commonly posed questions are often met with answers about as true as Moses’s promise to Pharaoh that the Israelites would return to Egypt after a three days’ journey. One is about dipping, the other is about singing, and both share a well-intentioned but arguably misplaced sympathy for our defeated taskmasters.

The first question arises in the heart of the Seder, in one of its most well-known customs, when we dip a finger into our cups of wine and remove a drop. This is done a total of 16 times—three times while reciting the biblical phrase “dam va’esh v’timrot ashan” (“blood and fire and pillars of smoke”) (Joel 3:3), ten times while enumerating the Ten Plagues, and then another three while reciting the acronym by which Rebbe Yehuda suggested we remember them—de-tzach adash be-achav. Why? The familiar and inevitable answer is some variation of “we diminish the joy of our liberation because of the pain the Egyptians endured during the plagues.” We are being taught not to lift a full cup of liberation if it isn’t tempered by a measure of sorrow for what our enemies have lost.

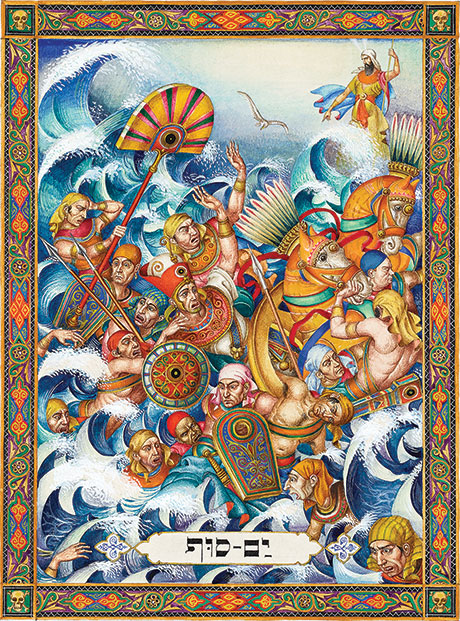

Our less-than-full-throated joy extends past the first days of Passover. Supposedly. During the holiday’s middle days and its final ones, a shortened, or “half,” Hallel is recited, in contrast to the full Hallel recited during the first two days. Here too, the usual explanation turns on diminishment. “It must be,” goes the refrain, “that we temper the recitation of triumphant singing by the winners as a sign of respect for the Egyptians, who lost.” As they say on the playground, “Be a good sport.” The midrashic prooftext for this is that as the splitting of the sea was taking place, God shushed the angels, saying, “My handiwork is drowning in the sea and you are reciting songs before me?” Common translations of this popular passage identify “the Egyptians” as the referent of “my handiwork” and add by way of elaboration that this indicates that God does not rejoice over the downfall of the wicked.

The problem is that neither of these answers is correct.

The first written source to mention the custom of dipping one’s finger in the wine is a Pesach sermon of Rabbi Eleazar of Worms (ca. 1176–1238), known as the Rokeach, after his famous book. He mentions several illustrious rabbinic families who followed this practice and provides several explanations for it, all with a common theme that wasn’t about empathy with one’s oppressors. “For each word a finger [goes] into the cup of wine and they spill out a drop, matching the sword of the Holy One, blessed be He, which has 16 sides,” he writes, based on a tradition from early Jewish mysticism. The Rokeach was famously fond of the numerical symbolism of gematria, so he also noted that there are 16 mentions of “pestilence” in Jeremiah, that the word “life” appears 16 times in Psalm 119 and eight times in the High Holiday Amida insertions recited once by the congregation and once by the cantor, that 16 men are called to the Torah during the week corresponding to the 16 sheep slaughtered in the Temple sacrifices, and that the numerical value of the Hebrew word hi (“it is”) in the phrase “it is the Tree of Life” (Prov. 3:18) is 16. Therefore, taking 16 drops of wine from the cup, Rabbi Eleazar says, “teaches us that we will not be injured”—note the pronoun—“and one should not ridicule the custom of our holy ancestors.” In short, those 16 drops of wine are about us, not them.

While the origins of customs are often notoriously hazy, and it remains within the realm of possibility that the spilled wine was once meant to symbolize the blood of our oppressors, the Rokeach explains that dipping one’s finger in one’s wineglass is what scholars would now call an apotropaic measure. It protects us from the Lord’s terrible sword of judgment. But what about the empathetic explanation? After all, it is often attributed to the 14th-century Spanish scholar Rabbi David Abudirham or the even more illustrious Don Isaac Abravanel (1437–1508). However, in a brilliant article in the Summer 2015 volume of Hakirah, Zvi Ron convincingly argued that these attributions are false and that the first instance of the explanation is actually in the writings of Rabbi Eduard Baneth, a German scholar who died in 1930. Ron suggests that someone or other later mistook a cryptic Hebrew attribution of the explanation to רב אב as referring to Abarbanel or Abudirham, rather than the relatively obscure Rabbi Baneth (whose first name begins with an aleph in Hebrew).

Whatever its provenance, the empathetic explanation of drips of wine reminding us of Egyptian suffering appealed to the universalistic sensibilities of American Jews. One finds it over and over again in American haggadahs—and not only liberal ones. Even the ArtScroll Haggadah says that the practice serves to diminish our joy.

And what of the Talmud’s seeming endorsement of rachmanus, mercy, for the slain slave drivers? Do we not abbreviate our own singing of Hallel in this same spirit, as some of the halakhic codes state? We do not.

As Basil Herring has documented in a learned study, the Talmud does not connect the aggada about the angels being told not to sing to the recitation of Hallel. After all, at issue there is whatever songs angels normally sing, not the humanly composed Hallel. And the Talmud states elsewhere that the reason “half Hallel” is recited on Passover is due to the nature of the Passover sacrifices when the Temple stood. Furthermore, earlier iterations of the midrash make it clear that it was the Israelites, not the Egyptians, who were meant to benefit from the divine shushing of the heavenly retinue since they have God saying, “My troops [i.e. the Israelites] are in danger, and you want to sing?!” As with the Seder’s finger dipping, it is apparently concern for the protection of the Jews that is at issue, not pity for our oppressors.

Much ink, let alone wine, has been spilled in wrestling with how best to express relief in a divine salvation that necessitated the death of others. Perhaps the impulse to empathize with the Egyptians who drowned in the Sea of Reeds springs from too distanced an attitude toward our own suffering, a failure to internalize the injunction to regard oneself as having been a slave in Egypt. It is easier to forgive what you can’t really remember. Indeed, one wonders whether even Rabbi Eduard Baneth, who taught for decades at the Hochschule für die Wissenschaft des Judentums in Berlin, would have spilled wine in memory of our oppressors had he lived just a decade longer, into that long night of European bondage and worse.

Discussions around the Seder table about the ethics of victory and victimhood, like celebrating Passover in a rebuilt Jerusalem, can wait until next year. The correct answers? Those can be given this year.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

Passover on the Potomac

As the holiday of freedom approaches, we explore two haggadahs—one old and one new—from our nation's capital, and think about the "audacious hope" of redemption.

Moses, Aaron, and Pharaoh Walk into a Bar: Passover in the Union Army

Yankee ingenuity at Passover: how one regiment made a Seder in the midst of the Civil War.

Redemption in Catalonia and Bosnia: The Sarajevo Haggadah

What does the most celebrated haggadah in the world tell us about exile and redemption?

Pour Out Your Fury

When the Bavarian government confiscated thousands of books from monasteries in 1803, among them was an utterly unique haggadah.

Yehudah Cohn

Stuart Halpern seems to conflate the origin of a practice with what he considers to be its "correctness". By this standard it would also seem incorrect to consider the holiday observed on the first of Tishrei as the beginning of the New Year.