Redemption in Catalonia and Bosnia: The Sarajevo Haggadah

The most celebrated Passover haggadah in the world—probably the most famous medieval illustrated Hebrew manuscript, period—is the Sarajevo Haggadah. Written and illustrated in northern Spain in the first half of the 14th century, it first came to public notice in the late 19th century, when an impoverished young man named Joseph Cohen (or Koen) from the Sarajevo Jewish community sold it to the newly founded Imperial National Museum of Bosnia in order to take care of his family. Exactly how this haggadah reached Sarajevo, and how it eventually came into the hands of the Cohen family some 400 years after the Spanish Expulsion, is unknown, but the subsequent history of the book is the stuff of legend.

Almost immediately after acquiring it in 1894, the National Museum sent it off to Vienna to be restored—Sarajevo was then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire—and commissioned two German scholars to produce a facsimile of the Haggadah with introductory essays. It was the first facsimile of an illustrated medieval Hebrew book ever to be published. Appended to the volume was a lengthy essay by the Hungarian Jewish scholar, collector, and bibliophile David Kaufmann that launched the modern study of Jewish book art. Indeed, the lavish illustrations in the Haggadah were themselves something of a shock to most scholars. Until then, it was commonly believed that the second commandment prohibited Jews from making any sort of image, a conception the Haggadah’s pictures dramatically belied. (Actually, the second commandment prohibits Jews from worshipping images, not making them.)

During World War II, after the fall of Sarajevo, the Nazis eagerly sought out the famous work in order to display it in the “Museum of the Extinct Race” that they were planning to build in Prague. It was saved by the museum’s chief librarian, Dervis Korkut, a devout Moslem and Islamic scholar, who bravely lied to the Nazi general who demanded the book, telling him that it had already been taken, and then hid it throughout the war (he and his wife also sheltered a young Jewish woman and are included among the Righteous Gentiles at Yad Vashem).

A half-century later, during the terrible Balkan wars of the 1990s, the Sarajevo museum was bombed by the Serbs, but the Haggadah was saved again, hidden away in a bank vault by the museum’s director, Enver Imamović. Today, the Haggadah is on display in the newly restored National Museum of Bosnia and Herzegovina, where it is kept inside a tall, tower-like glass case in the museum’s trophy room dedicated to Bosnia’s greatest treasures.

As a survivor of two of the 20th century’s worst genocides, the Sarajevo Haggadah has become a kind of icon of fin de siècle Sarajevo, when Christians, Moslems, and Jews lived in peace, a memory romanticized in the Geraldine Brooks best-selling novel about the Haggadah, People of the Book. It has also become the most frequently reproduced medieval Jewish illustrated manuscript. After the original publication in the 1890s, no fewer than four additional facsimiles have appeared, some of them in multiple printings. And now, the best facsimile of all has appeared, published under the auspices of the National Museum of Bosnia and Herzegovina and produced with state-of-the-art digital technology that makes every previous edition literally pale in comparison. The Haggadah’s extraordinary coloring now emerges in all its rich glow, the detailed decoration is fully restored, and the gold leaf in the initial panels actually shines.

The new facsimile is accompanied by a book-length study by the distinguished Israeli art historian Shalom Sabar, the most comprehensive and complete analysis of the Haggadah yet written. The study includes a full description of the book’s history, an expert summary of the abundant past scholarship about its illustrations and text, and an original and insightful treatment of the world in which the Haggadah was produced and which its illustrations frequently picture.

The Passover haggadah is the exemplary Jewish book of redemption. By famously enjoining its every reader to see him or herself as having come out of Egypt, the haggadah also imagines the redemption to come, whether it is soon or in the distant future. And yet, the haggadah’s developing text and changing illustrations trace the different ways in which Jews have conceived of redemption through the course of history. As Jews have moved from one temporary home in the diaspora to another over the last thousand years, their images of exile and redemption have repeatedly been shaped by the cultures in which they have lived. Indeed, what the haggadah shows is how exile and redemption are intrinsically linked in the Jewish imagination.

The Sarajevo Haggadah is one of a group of seven surviving illustrated haggadot that were produced in Catalonia, part of the Crown of Aragon, in the first half of the 14th century. By this time, Catalonia had long been under Christian rule, and the illustrations and decoration of the Haggadah largely mirror those of contemporaneous Latin Christian manuscripts, although the Sephardi script with which the text is written still recalls the swooping letters and scimitar-like shapes of Iberia’s Arabic-speaking Islamic past. As Sabar notes, both of the anonymous Jewish artists of the Sarajevo Haggadah were “well rooted in the surrounding visual culture of the time,” who worked “time and again to fit Jewish ideas, commentaries, and midrashic elements” into their art.

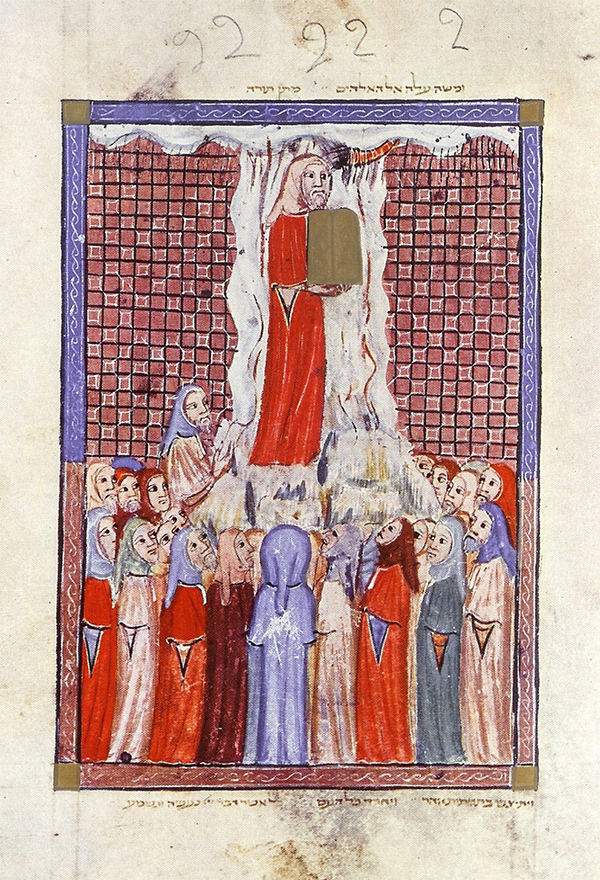

The most striking feature of the seven Catalonian haggadot is a series of Bible illustrations that serve as a kind of prologue to the haggadah’s text. The series in the Sarajevo Haggadah is the most complete and begins with the first day of biblical creation. In the other Catalonian haggadot, the series opens with either the birth of Moses or the moment in which God speaks to him out of the burning bush. Wherever it begins, the series then proceeds scene by scene through the books of Genesis and Exodus, picturing the lives of Adam and Eve, Noah, Abraham, Isaac and Jacob, and Joseph and his brothers in Egypt, then the Exodus with all 10 plagues and the crossing of the Red Sea (and, in some haggadot, Mt. Sinai and later scenes). At this point, though, the illustrations typically switch seamlessly to a brief group of pictures illustrating contemporary Jews in Spain preparing for Passover, getting haroset and matza from a communal kitchen. The illustrations of most of the Catalonian haggadot conclude with an illustration of a family returning home from the synagogue on Passover eve to begin the Seder, whose initial text, the Kiddush, the blessing over wine, follows on the very next page. The effect of this series is to collapse historical time so that the history of the world culminates in the very Seder table around which the haggadah’s readers are seated.

As scholars have long recognized, these Bible pictures are not so innocent. The elongated and swaying figures in the Sarajevo series (and in many of its Catalonian counterparts), as well as the iconography of many of the illustrations, are based on Latin psalters of the 12th and 13th centuries (even if the pictures in the Christian books are usually better drawn). In the psalters, however, these illustrations carry a clear ideological message: The Old Testament pictures invariably anticipate the life of Christ in the New Testament. For Christians, this is the Bible’s real story. During the same centuries, Christian preachers also began to deliver a new message: that their Jewish contemporaries were “talmudic” Jews whose religious beliefs and practices were based not on the Bible but on later rabbis’ inventions and fabrications. As the Israeli art historian Sarit Shalev-Eyni has proposed, in moving directly from the Bible to contemporary Jewish life, the biblical illustrations in the Catalonian haggadot aimed to refute this claim. They make a visual argument that present-day Jews are the true heirs of the Bible.

This message is the kernel of the Sarajevo Haggadah’s singular conception of redemption. Other features of the illustrations fill out that conception. Many of the pictures directly borrow visual details from midrashim and other later Jewish exegetical texts that would have been familiar mainly, if not only, to Jews. An inordinate number of pictures are devoted to scenes from the lives of Joseph and Moses, two Jewish “lads” who attained prominence in the courts of foreign rulers in the course of careers not unlike those of the Jewish courtiers who served in the courts of Moslem and later Christian rulers in Iberia and who, according to Sabar, were most likely to have been the patrons who commissioned these expensive haggadot. The biblical figures are regularly pictured as contemporary Sephardi Jews.

Still other details in the haggadot point even more directly to the Iberian context of these books. In the Catalonian haggadot, maror, the bitter herb, is usually illustrated not as a head of bitter lettuce (let alone a slab of horseradish) but as an artichoke. As Sabar notes, Rabbi David Abudarham, the foremost Sephardi halakhic authority of the period, actually identifies maror as the cardoon (Cynara cardunculus, the “artichoke thistle”), which, as it happened, was cultivated and widely used in the medieval Spanish kitchen. Alas, the artichoke never made it beyond Spain into standard Seder practice.

I have long taught and studied the Sarajevo Haggadah, and I own every facsimile that has been published, but, to tell the truth, I never thought that it was the most beautiful or important medieval illustrated haggadah. Yes, it has a great story and the most complete cycle of illustrations, but other haggadot—the Golden Haggadah and the mysterious Birds’ Head Haggadah, to name just two—always seemed to me more interesting visually and historically. I was never so impressed by the Sarajevo Haggadah’s uniqueness. That is, until I went to Sarajevo and actually sat with the Haggadah for several hours (although Andrea Dautović, the kindly librarian who showed me the book, insisted that she, not I, turn the pages). Looking directly at the parchment pages of the Haggadah, I saw what I had never seen before—the brush-strokes, the wine-stains, the doodles in the margins of some of the illustrations that some child (or adult?) had drawn while they practiced writing over and over again a something that looks like either the letter S or the number 2, at some time in the Haggadah’s travels. I saw, in short, that concrete singularity of the book, and felt what Walter Benjamin famously called the “aura,” the halo surrounding an original work of art, that is inevitably lost in any reproduction no matter how precise.

As we sit at the Seder table and remember the Exodus from Egypt, and pray, “Next year in Jerusalem,” some of us may want to add, “In Sarajevo, too.”

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

The Chief Rabbi’s Achievement

Lord Jonathan Sacks is the most gifted expositor of Judaism in our day, and has written more than 20 books that are both learned and very accessible.

Poets of the Tribe

The story of 12 Hebrew poets—in America.

A Decade of Recommendations

In celebration of our 10th anniversary, we asked 10 of our favorite readers which books they had found themselves recommending the most over the last decade.

Belt, Road, and Risk

When Prime Minister Netanyahu visited the White House in 2019, President Trump was said to have put the same point more bluntly: Washington’s security will be compromised if Jerusalem and Beijing grow too close.

Esther Hornik

Dear David, I was with Shalom Sabar, on a Jewish Historical Tour, when the formerly closed museum in Sarajevo was opened just for our group and we got to see an open illuminated page of the Hagaddah. This was an inspirational experience because, despite the deep religious and political divisions in Sarajevo, we were allowed to see an illuminated page of this beautiful book.

We have to hope that Jews will survive for many years to come like the Sarajevo Haggadah. Have a Happy Passover, Esther