Friendship?

In 2017, the jury of Tilburg University’s E. du Perron Prize honored the Belgian writer J. S. Margot’s “fascinating book in which she provides a glimpse into the closed community of an Orthodox Jewish family,” the Schneiders of Antwerp. Mazel Tov: The Story of My Extraordinary Friendship with an Orthodox Jewish Family—translated into German, French, Polish, Czech, Hungarian, and now English—“shows how, despite major differences,” people “can learn from and live with each other,” the jury said. No less than Belgium’s Queen Mathilde praised Mazel Tov as a book that touched her “deeply.” Writing in the Guardian, the critic Toby Lichtig commended the author’s “empathetic outsider’s perspective.”

Empathy, however, is severely lacking in its pages. This is a book that is neither about a friendship in any real sense of the word nor demonstrative of the author having learned much from the Schneider family at all. Rather, Mazel Tov is a memoir about Margot’s ignorance of the Modern Orthodox world—which very occasionally manifests as low-level antisemitism—and ultimate failure to comprehend it.

Her relationship with the Schneiders began in 1987, when Margot was studying at Antwerp University’s Higher Institute of Interpreting and Translation Studies. On a bulletin board by the canteen was a job notice: a family needed a student to tutor their four children ages eight to sixteen. Margot was warned that the family was Jewish, and her unfamiliarity with Jewish life in Antwerp is obvious from the outset. When she shows up at the Schneider home for the first time, she wonders about the “transparent tube” hanging by the door, taking the paper inside to be “a kind of fortune cookie, a note with a thought-provoking saying to cheer up your day.” It also takes her a while to figure out that the doorbell is linked to a security camera. Her parents, by contrast, leave their back door unlocked all day.

The Schneiders—husband, wife, and four children: Simon, Jakov, Elzira, and Sara—are Modern Orthodox, and they take pains to distinguish themselves from Antwerp’s ultra-Orthodox, who today constitute about 40 percent of the 18,000 Jews residing in the city. “We go to different synagogues and have different rabbis. Hasidic children go to different schools, which are much stricter about religion than ours,” Mr. Schneider tells Margot. The family patriarch—a Holocaust survivor, one of only a few hundred in Antwerp—is a diamond merchant, a trade in which Antwerp’s Jews have been engaged since the end of the nineteenth century. Both his office and the family home are located in the city’s Jewish neighborhood.

The first interactions between Margot and the Schneiders are quite uncomfortable. She extends her hand to Mr. Schneider, who agrees to shake it in return, albeit just this once. Mrs. Schneider probes the author about her personal life, including the fact that she lives with her boyfriend, even though they aren’t married. She seems put out by the fact that Margot’s boyfriend is from Iran—or “Iraaaannn,” as she ruminates—and a Muslim. “You are a young and sensible woman,” Mrs. Schneider remarks. “And your husband lives in the country of the ayatollahs.” She seems not to understand that he is a refugee living in Belgium.

Despite the rocky introduction, Margot gets the gig. Eventually, principally via her relationship with Elzira, who is twelve years old when the memoir begins, Margot enters into the family. She helps Elzira with her homework and teaches her how to ride a bike, and Elzira, in return, becomes Margot’s instructor on Judaism, teaching her about Jewish dietary law, how and why Mrs. Schneider styles her hair, and what an eruv is. At a Shabbat dinner, Margot reflects: “Sitting there I believed that people and peoples who sang together had a stronger bond than people who didn’t, and for my own part I felt this lack.” Margot worked for the Schneider family for six years, until Elzira’s graduation from high school in 1993, and their relationship continued even after she was no longer their tutor.

Mazel Tov is, for all its faults, an artfully rendered memoir. By arranging her journey episodically in well-written chapters that last just a few pages, Margot overcomes the shapelessness of real life, giving it a narrative arc. Margot’s book is also a product of its European context. Polled by Pew in October 2019, more than half of Europeans expressed a favorable view of Jews: from 92 percent in the Netherlands and Sweden to 51 percent in Greece. At the same time, the European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights found in 2018 that 85 percent of European Jews believed antisemitism was a problem in their respective countries, with the agency concluding that “many Jews across the EU cannot live a life free of worry for their own safety and that of their family members and other individuals to whom they are close.” Antisemitic incidents went up 6.4 percent in Austria between 2019 and 2020, and Britain’s Community Security Trust in 2020 logged the third-highest number of antisemitic incidents ever recorded.

One explanation for this contradiction or disconnect may be that, as a consequence of the Holocaust, a working knowledge of Judaism as a religion or lived experience among Europeans has receded, with Judaism associated more with death than life, past than present. In major cities, Antwerp being one, Jewish communities are strong but undeniably shrunken. For most Europeans, contact with Judaism occurs inside a museum or through Holocaust education. A guide from the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) for the teaching of Judaism in schools notes that “since Jewish communities tend to be concentrated in certain areas, many students may have had few, if any, opportunities to get to know Jewish people or to learn about Jewish traditions and the religion of Judaism,” leading to a “lack of contact and understanding.”

Before working for the Schneiders, Margot had heard of neither Purim nor the Purim story. She did not know about state-funded Jewish schools that taught secular subjects alongside religious ones. She did not understand that Elzira could not eat a chocolate croissant that did not come from a kosher bakery. As if to make the OSCE’s point, Margot writes: “The only Jewish person most non-Jews in my country knew was Anne Frank.”

Her initial ignorance is, of course, forgivable, yet Margot’s subsequent exploration of Judaism is oddly passive and often uncomprehending. She seems surprisingly incurious for someone who would go on to become a writer and journalist. It is left to the Schneiders to deliver lessons about Jewish life. In his Guardian review, Lichtig notes Margot “never really gets to the heart of what she nicely describes as ‘the millefeuille of Jewish culture,’” referencing the airy pastry with a name that means “one thousand layers.” That would be understating things. She barely even tries.

She takes in the whats and wherefores of Judaism but is never quite able to grasp the why: why someone would wish to be Modern Orthodox and live a life according to the strictures of traditional Jewish law. To be “empathetic,” as Lichtig describes her, would be to come to terms with those things about Orthodoxy with which she disagrees. Instead, her tendency is to fight against the possibility of comprehension, each new piece of information provoking a cacophony of objections, often phrased as rhetorical questions:

So religious Jews separated themselves from the rest of the population very deliberately and from a very young age. What possessed them? How could a minority seek to distinguish itself so strongly from the majority? Who, apart from the whites in South Africa, sought to protect their identity by isolating themselves? How self-righteous—or fearful—would you have to be for that? How blind to your own history? It wasn’t so long ago that Germany and its cohorts had viewed this tight-knit people as public enemy number one. Yet now, not fifty years later, they still wanted to isolate themselves? In the army, everyone knew that camouflage could save lives. But these people, of all people, with a history of persecution, were trying to do everything they could to be noticed?

Once or twice, Margot comes close to something like self-awareness: “Or was there something I was failing to understand? To see?” she asks. “Did the problem lie with me?” Such questions hold out the possibility of transformation, yet throughout Mazel Tov, Margot continuously fights against it as if the prospect of some sort of realization or understanding appalls her.

Sometimes the void left behind by her lack of empathy and understanding is filled by something more insidious. What precisely does Margot mean when she writes of Mr. Schneider, “He looked a bit like my father, but a Jewish version”? Why does she compare Jakov with Sig Arno, the German Jewish comic movie actor who had dark hair and a “beaky nose”? “Compared to Arno’s great schnozz,” Margot continues, warming to her theme, “Jakov’s was a miniature.” These remarks, from the book’s first fifty pages, may be an attempt to foreground her maturation, but since that maturation never comes, such antisemitic stereotypes or sentiments cannot be overlooked.

Margot also has a habit of bringing up the Israeli-Palestinian conflict in contexts where it doesn’t quite belong, using it as a cudgel with which to beat the Schneiders as if they bear responsibility for Palestinian statelessness. It would not have been Elzira’s fault, for example, that while she was studying in Jerusalem, her rights differed from those of a Palestinian living in the same city, or indeed, in the West Bank. Yet Margot—who had been corresponding with her—wonders if she was being “tactful or hypocritical” not to point out that Elzira had “overlooked the Palestinian population” in her letters.

When Margot visits Elzira in Israel, her first impression of Tel Aviv is rather predictably one of disappointment. She wonders where the “Muslim men or women” and “street signs in Arabic” are—both of which she could have found there had she cared to look. She meets Elzira in the Orthodox city-suburb of Bnei Brak, where the Schneiders’ eldest son, Simon, is now living. Simon signed up for a stint in the IDF after finishing his high school education in Antwerp, serving on the Golan Heights, before beginning his medical studies in Israel. By the time Margot sees him again, he is a doctor, working at a clinic in Tel Aviv and living in an apartment in Bnei Brak with his Anglo-Dutch wife, Abigail.

Margot joins Simon and Abigail, Jakov and Elzira for a Friday night reunion—something like old times. Far from being happy about their reunion, Margot lies awake in her bed, kept up “by the image of Simon as a young soldier,” defending Israel “tooth and nail” while making “decisions about the lives of Arab inhabitants”:

Why had we avoided this subject so consciously during the meal? Didn’t silence mean complicity? Had the children become more radical? Did they no longer believe in a two-state solution, as we—especially Jakov and I, at his desk—had often discussed?

By Mazel Tov’s conclusion, the Schneiders have dispersed. The parents are in New York, and Margot talks to them on the phone a final time. “Why are you too frightened to open the doors a little wider,” she asks them, “so everyone can peep inside?”

“We, the Jewish community of Antwerp, cannot be open. Not as you would like,” Mr. Schneider replies. “You know a little bit about our history. So you should understand that.” But Mazel Tov, it turns out, is mostly the memoir of a European’s failure to comprehend such things.

Suggested Reading

A Rejoinder

I didn’t know that there was anyone left in the academic world who held as simplistic view of history as the one that Eric Alterman espouses in his response to my review (“Context and Content,” Winter 2023). The historian’s job, he says, “is not to voice disapproval or approval” of anything. Consequently, he endorses “nothing and no one in this…

Nothing but Blue Skies

Irving Berlin was generating Tin Pan Alley hits before Ronald Reagan was born and was still writing lyrics when the elderly Reagan occupied the White House.

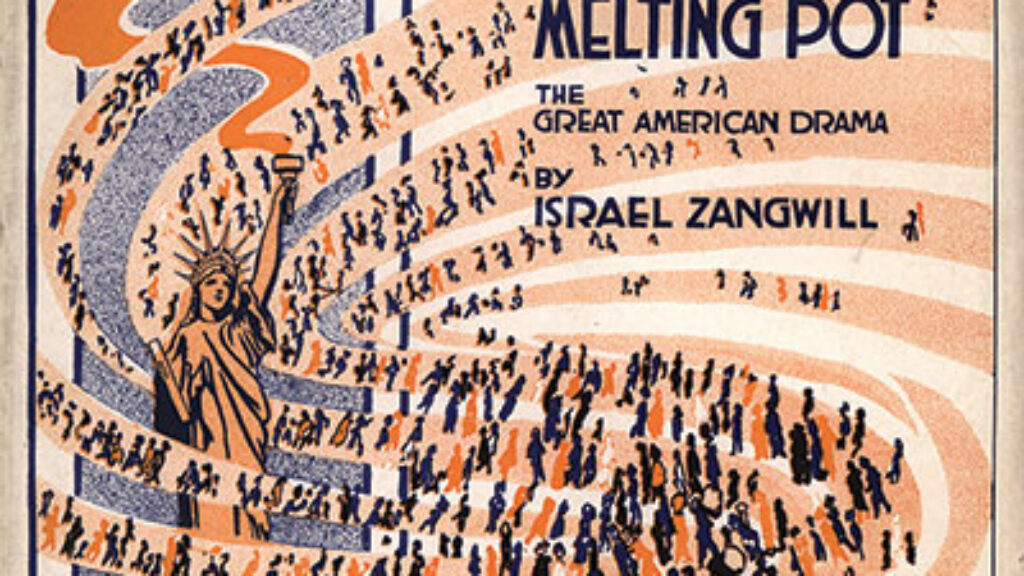

In the Melting Pot

More than a century after Zangwill's play debuted, the melting pot is still bubbling. What does that really mean for American Jewry?

Proverbs 8:22-31

Many have marveled at the wisdom of the biblical books attributed to King Solomon. Here, in a new translation by Robert Alter, is Proverbs' account of the birth of Wisdom herself, from The Wisdom Books: Job, Proverbs, and Ecclesiastes: A Translation with Commentary, now out with Norton.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In