Moshkeleh the Thief

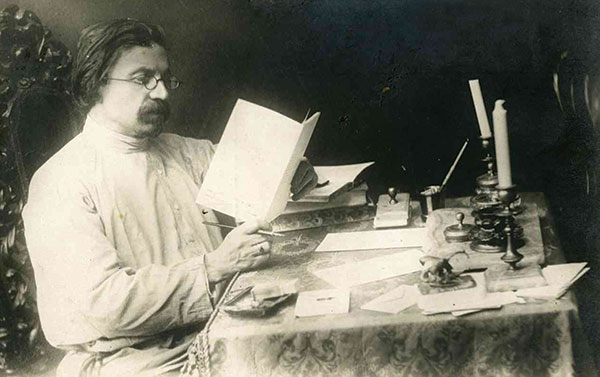

A few years ago, I read an article in an old issue of the great Israeli Yiddish journal, Di Goldene Keyt, which mentioned a work by Sholem Aleichem that I had never heard of: a short novel called Moshkeleh Ganev. This surprised me. I had already translated four volumes of his stories and his autobiography. Moreover, I owned the complete 28 volumes of Sholem Aleichem’s collected works. Even if I hadn’t read every single page, I certainly knew its contents.

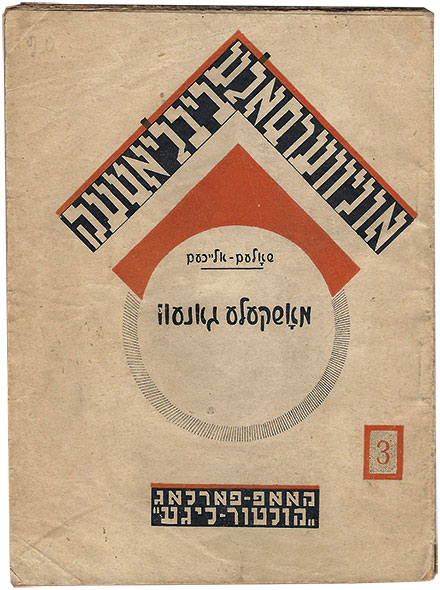

I soon learned that Sholem Aleichem wrote this novel about a horse thief in 1903 and serialized it that year in a Warsaw Yiddish daily. Moshkeleh appeared in book form 10 years later in Warsaw, was republished in 1927 (Kiev) and again in 1941 (Moscow), but was somehow omitted from his collected works, and thus largely forgotten.

Incidentally, the Kiev and Moscow editions followed the Communist edict that all Hebrew words had to be spelled phonetically in Yiddish. Thus, the word “kosher” כשר became the scarcely recognizable קאָשער. Ostensibly, this was to help readers who did not know Hebrew read the text, but of course, it was also part of an antireligious policy. The 1941 Moscow edition of Moshkeleh, published at the height of the Stalinist period, somewhat surprisingly has a four-page glossary that cites and correctly explains all the Hebrew words. (An inadvertent benefit of this policy is that it shows us how Yiddish speakers in Russia pronounced those Hebrew words at the time.)

Prior to Moshkeleh Ganev, Sholem Aleichem had never devoted a full-length work to the Jewish underclass. In fact, it was a first for Yiddish literature, with its riveting plot about a rowdy, uneducated horse thief who falls in love with the flirtatious daughter of a tavern keeper. Sholem Aleichem’s commitment to capturing their world and their language was plain from the outset. Here is how the book begins:

Non-Jews called him Moshke. Jews stretched out his name to “Moshkeleh” and then added the nickname ganev, or “thief”— for that’s what he was, a ganev. Which means, he earned his livelihood by thievery.

But when it came to stealing, the only thing he stole was horses. In thieves’ lingo, one doesn’t say “I stole a horse.” Rather, when speaking of their work, horse thieves say, “I shot a bird,” or “I freed it from the stable,” or “whistled it out of the shed,” or “I fiddled it out of a gypsy,” or “whipped it out of a waggoner.” That’s the jargon of horse thieves.

In fact, even the word “ganev” wasn’t part of their vocabulary. A pickpocket was called “nimble fingers.” One who worked in the dark was “a fly by night.” A thief who stole from folks fast asleep at home was “an undercover man.” A ganev of garments—“a coat collector.” And a plain, run-of-the-mill robber was “a snatcher.”

Moreover, the words “horse thief” were never articulated either. However, someone who had a great love, or amour, for horses—a man like that was called an “amateur.”

And Moshkeleh Ganev was a great lover of horses. He adored horseflesh. Since childhood, his daily fare had been riding a horse, flying like arrow out of bow, jumping madly over hill and dale, into forests and across streams. His acquaintance with horses came via his father, Yoineh the Prophet, a lifelong horse thief.

Sorry! Not a thief, but a “prophet.”

You know what a prophet is? Among horse thieves, horse dealers, and coachmen, a prophet is a know-it-all, a man who always gets it right.

Although Sholem Aleichem could not have known it, his great contemporary Anton Chekhov praised precisely this kind of realism when, a few years earlier, he wrote to a friend, “To depict horse thieves in seven hundred lines, I must all the time speak and think in their tone and feel in their spirit.” But, of course, he is just as convincing (and comical) in depicting Jews shopping for their Passover wine or the Seder of a drunken tavern keeper.

To-be-continued fiction was popular in the Yiddish press, and Moshkeleh Ganev was serialized weekly, with each chapter ending on a note of uncertainty or suspense. Thus, the first of the two chapters included here, titled “Jews Buy Wine for the Seder,” ends: “something had happened to our Tsireleh.” The next week’s selection, “This Pesach Night,” ended on an even more ominous note: “And then he brought her to the monastery.” Will Tsireleh convert to marry the tall, handsome Maxim Tchubinski? Will she be saved? What will Moshkeleh, who has loved Tsireleh for so long, do?

Sholem Aleichem’s own view of Moshkeleh Ganev is reflected in a letter he wrote in 1903: “I now feel as if I’ve been born anew, with new—brand new—strength. I can almost say that now I’ve really begun to write. Until now I’ve only been fooling around.”

Chapter 14

Jews Buy Wine for the Seder

Throughout the year, Chaim Chosid’s wine cellar is open to the town worthies. But on the Eve of Pesach, Chaim and his entire family, including the wine cellar and all its wine, are held in bondage to the Children of Israel in Mazepevke.

To get a sense of what happened at the Exodus of the Jews from Egypt, please come down to Chaim Chosid’s cellar when the Mazepevke Jews buy wine for the Four Cups of the Seder.

All year long, Jews manage to survive, thank God, without wine. They make Kiddush over challah and drink water from the stream. But with the approach of Pesach, they get spoiled and pampered. They prepare themselves to become kings at the Seder, as tradition prescribes. Now they think they’re sophisticated connoisseurs and experts in wines.

At this season, plain wine is nothing but junk. For Pesach, people demand a Vermouth, and a fine one at that, from the best vineyards. But hold it! A plain Vermouth is junk too. It should also have a hint of Merlot. But that too is bilge water. For it should be blended with a wine that makes the tip of your tongue tingle and doesn’t give you heartburn, but yet is strong and goes down smoothly.

“You know, Reb Chaim, you know what I want. The one I bought last year, remember?”

Such are the remarks Chaim Chosid hears the day before Pesach and not just from one man. He hears this from ten, twenty, fifty of the town’s Jews at the same time, for all of them postpone getting their Four Cups till the last possible day, the final hour, the very last minute.

And no matter how much Chaim scolds them for shopping so late, it helps like cupping helps a corpse. It just doesn’t sink in.

“You’re absolutely right,” they say but continue to do what they’ve done in the past.

On this day, neither Chaimova nor her daughters work in the cellar alone; Chaim Chosid himself joins them along with his sons-in-law. One pours wine, one washes bottles, one offers samples. A veritable racket encompasses the cellar: shouts, noise, tumult. One customer’s order was mixed up—he got the wrong bottles of wine; that one didn’t pay; another’s bottle broke, and he stands there, his fingers around the corked glass neck, asking:

“What should I do now?”

Another customer yells:

“Give me two liters of the kind I got last year, and one from two years ago, but a bit stronger.”

Chaim Chosid and his sons-in-law have to be tougher than steel to endure all this. It’s enough that Eli Noah—imagine that!—he who wears a silk cap in mid-week, has to be a servant to Mazepevke Jews one day a year. But he has no choice.

That’s why there is one day a year when the women must be free of their daily responsibilities so they can bring the holy Pesach into the house, dress up and look good in the best possible manner, and become queens at the Seder, as God has ordained.

With all the preparations for the sacred festival completed, Chaimova and her daughters changed clothes, dressed up in the finest way, and became queens at the Seder, indeed as God has ordained. Shining and glittering in satin and silk, with pearls and diamonds, they looked so elegant one should have painted a portrait of them.

But Tsireleh’s conduct was not like that of the others on this Eve of Pesach. She didn’t want to dress up and primp as in years past. She looked worried, distracted, her face pale with blue rings under her eyes, like a person who could not sleep all night long and wept throughout the night.

Something had happened to our Tsireleh.

Chapter 15

This Pesach Night

We consider the beloved Uncle Pesach sweet and dear for lots of reasons.

It is sweet and dear because it reminds us that long, long ago, we were liberated from the Exile of Egypt. Pesach is also sweet and dear because it comes just at the time when the entire world itself awakens, liberated, renewed, and revivified. The earth catches its breath, and the sky speaks, sounding out thunder and lightning.

Everything is born afresh. Endless joy!

The holiday is also sweet and dear because poor and dejected Jews toil hard, alas, and struggle, and just barely, in the nick of time, amid great trouble, angst, and tribulations, bring in the holy holiday. Now, finally, they can rest and relax for eight days in a row.

And when I recall the name of the beloved and sweet Uncle Pesach, my happy childhood, the sweet world of my youth, rises up from the grave and sends me greetings from those precious years that will never ever return.

But if Pesach is a holiday, then the first night of Pesach is a double festival, a holiday’s holiday.

__________

Everything was quiet in Mazepevke on that Pesach night; all was tranquil and festive. Chaim Chosid concluded the Seder; he had eaten the knaidlakh, accompanied by good wine, and felt full as a drum with singing the long final song of the Haggadah, the “Chad Gadya.”

While still at the table, Chaim Chosid felt he was dozing off. He had just rushed through the Song of Songs, chanted after the Seder—God alone knows if he had managed to finish it—for entire sections swam away from him right before his eyes, just like part of a journey seems to vanish, made shorter when one is lost in thought.

So Chaim Chosid quietly slipped away from the table, undressed—and what about the bedtime “Shema,” the Hear O Israel prayer? What Shema? Where Shema?—sank into bed, and fell asleep at once.

And all the sons-in-law, who at first competed with one another to show off their refined taste in wine drinking, slowly became so drunk that when they rose from the table, they could barely stand on their feet.

Eli Noah was drunk as Lot, so soused he wouldn’t even have noticed had they tied him up and thrown him outside.

True, when he stood up, he pretended to sing something from the Haggadah, stretching out a refrain from the song, “It Happened in the Middle of the Night.” But his slurred words made him sound so ridiculous, and his face look so foolish, his wife had to take him by one finger and lead him away, like a calf, forgive the comparison, is taken to its mama.

“Come on already. Off to bed. . . . You got yourself all boozed up and you’re still singing away.”

And that is how on this Pesach night after the Seder at Chaim Chosid’s house, each person crept off to his room. Soon snoring and whistling from many throats and noses, in various tones, resounded throughout the house.

But Tsireleh was the only one who was not asleep.

__________

On that Pesach night, Tsireleh bade farewell to her father’s house. She got out of bed and, wearing a shawl on her head, a dress, and a pair of shoes, Tsireleh quietly slipped out the door.

Waiting for her there was a tall, handsome man.

Maxim Tchubinski.

It was a warm, dark night. Stars were hidden behind murky clouds. They did not want to witness a Jewish girl abandoning her father’s house on such a holy night. A soft drizzle was falling, warm tears trickling from the sky, weeping for the tragedy that had befallen Chaim Chosid and his family. Still completely oblivious to what had happened, they slept the sweet sleep of happy, sincerely pious Jews on that holy festival, the most joyous of all the holidays.

Had someone woken up during that night and merely looked at Tsireleh, she would have turned back. But no one woke up. Everyone was fast asleep, in deep sweet holiday slumber.

Tsireleh, however, was shivering like a lamb, at which Maxim Tchubinski calmed her with sweet golden words, saying as he hugged her:

“I love you so much. I’m so happy you listened and did what I asked you to do. And soon we’re going to be so happy together.”

Tsireleh burst into tears out of abundant happiness but also out of fright at what she had done, trusting Maxim completely and placing herself totally in his hands.

And then he brought her to the monastery.

Excerpts from Moshkeleh the Thief, which is now available for preorder, are reprinted with the permission of The Jewish Publication Society.

Suggested Reading

From Moses to Moses to Sholem Aleichem

Anyone looking for a single-volume introduction to Jewish civilization for a class full of highly educated professionals with only a limited knowledge of the subject will find nothing better in print.

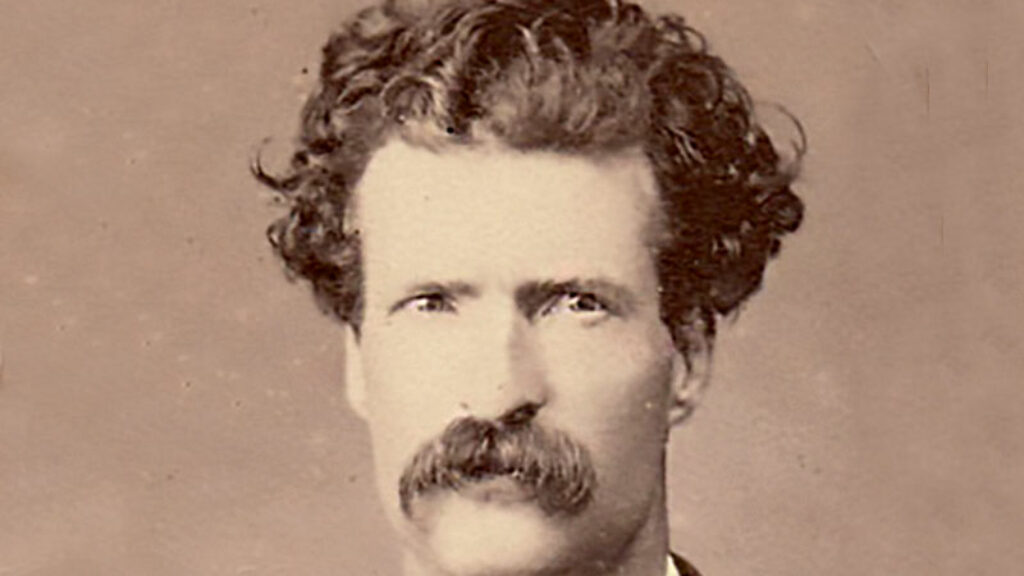

Not So Innocent Abroad

Mark Twain's book about his travels to the Holy Land and back is his bestselling book over the course of his lifetime and remains one of the bestselling travel books of all time.

The Old Country, Twice Removed

My grandfather had a way of mentioning the Kiev guberniya (province) that made it sound to me, when I was a boy, like it was our place in the Old Country—and more than half a century later, it still does.

Translating and Remembering Chaim Grade

A memoir of faith, literature, and chickens.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In