The Story They’ve Been Telling Themselves

During the war, they were heroes. Eva Panić forged documents and smuggled weapons and money to Josip Tito’s Communist fighters; her husband, Rade, fought with the partisans. The unlikely couple—she was a cultured Jewish girl from a wealthy Yugoslav family, and he was the son of Christian Serbian farmers so impoverished he enrolled in a military academy where he would at least have enough to eat—were formidable. The pair also hid people wanted by the Nazis in their home, saving 1,500 Serbians from the concentration camps. And they were deeply in love. Pictures show them gazing at each other in complete adoration.

After the war, they had a daughter, Tiana, and moved in the top circles of Yugoslav society. Rade, commissioned as a cavalry officer, represented the country in equestrian competitions and was as dashing as a prince on his steed. And then it all fell apart. Rade caught the attention of the UDBA, Yugoslavia’s internal security service. He was arrested and accused of being a Stalinist, spying for Russia to try to weaken the rule of Josip Tito. After three days of interrogation, he hung himself in his cell. Eva was picked up next and asked to sign an affidavit that validated the accusations.

“I wouldn’t turn on my beloved, my sacred husband,” she tells filmmaker Avner Faingulernt for the documentary Eva, released in 2002. She would go to prison if she didn’t sign, the interrogators threatened, but she refused. She had Tiana, then six, to take care of, they reminded her. If she was jailed, came the threat, Tiana would be “on the street.” Still, her decision was clear: “I loved him more than I loved her.”

Mother and daughter were reunited only after Eva spent almost three years on Goli Otok, Yugoslavia’s brutal prison island. During that time, Tiana lived with her aunt and uncle, traumatized Holocaust survivors who abused her and then sent her to an orphanage. Eva’s decision devastated Tiana and caused a deep estrangement between her and her child, but decades later, she remained unmoved: “I would make the same decision today.”

The novelist David Grossman, who first came to know Eva as a woman of seventy-seven living on a kibbutz in northern Israel, describes her as “a mixture of a very tough person when it came to ideals and ideas and values,” but “the softest person when it came to human beings, to empathy, to help, to feel something for the other.” In his latest novel, More Than I Love My Life, he has fictionalized Eva and Tiana as Vera and Nina, two of the book’s three central characters. The resulting novel explores the ramifications of the moment when Eva/Vera had to choose between those two sides of herself,

between the idealist who promised never to betray her husband and the mother of a young child.

While Grossman came to know Eva well over the course of their twenty-year friendship, his novel introduces the character, Vera, at a remove. The reader experiences this unique woman through the eyes of an Israeli granddaughter named Gili, which, she tells the reader, is “a problematic name whichever way you look at it, being not only derived from the Hebrew root for ‘rejoice,’ but phrased in the imperative.” Gili, who works in film as a “script girl,” capturing all the tiny details that will be needed for editing and continuity, has also become the repository of Vera and Nina’s stories from before she was born. It’s a bitter legacy.

Grossman’s women are astonishingly well conceptualized and created with a level of skill few male writers can match. Reading him speaking through Gili never feels like ventriloquism; he inhabits her fully. Readers of Grossman’s To the End of the Land will not be surprised. With the same sensitivity and depth that he portrayed Ora, an Israeli woman who decides that her son will not die in combat if the IDF can’t find her to notify her of his death, he depicts how trauma and lies, abandonment and betrayal, warp relationships and the people in them.

Grossman presents the ugliness of this story in beautifully rendered prose that entrances in part from the juxtaposition. Just as a well-cut stone benefits from a loupe, his pages will be enjoyed more by a close reader. On second and third readings, one is still seeing new facets. One could use Grossman’s own words—describing his first experience reading Sholem Aleichem as a young boy—to describe the effect of his storytelling: “It all worked its magic on me in a muddled way, the words with the biblical ring, the characters, the customs, the ways of life.”

In telling her family’s story, Gili uses the language of myth and fairy tale, with references to hunchbacks, dragons, and the like dotting the pages. Vera paints herself as a kind of Cinderella on the kibbutz, where she has come to live with Nina. After she is remarried to a man “who had been known throughout the kibbutzim of Israel as a desirable widower” named Tuvia, “the ladies in charge of the work schedule assigned Vera to week after week of cleaning and mopping in the dining room”:

At the end of her shift she would come home to Tuvia and show him her hands, with their skin peeling off and eaten away by detergents, and her grimy, broken fingernails. Tuvia would soak her hands in warm water with chamomile, then apply nail polish—Vera used to imitate him, with his tongue between his lips. “Chin up,” he would always say. And just like that, with her head held high and her nails held out like ten glistening drops of blood—“I am proletariat in my soul! No job is too low for me!”

Although one might expect Vera to be a wicked, or at least indifferent, stepmother, she becomes fiercely protective of her new stepson and beloved by her new family. But Grossman also evokes Snow White, with Nina watching Vera, preparing to go out in the glamorous years in Yugoslavia after the war, putting on “makeup in front of . . . an oval mirror adorned with bronze vines that hugged her figure.” Not an exact match for the cartoon version, but close enough.

While the book’s present-day is 2008, the “once upon a time” of More Than I Love My Life is the early 1960s on a kibbutz in northern Israel. Rafael, the recently orphaned son of Tuvia, is pulled out of the fog of his grief when he notices Nina, “a fair-haired girl of seventeen whose long face, which was pale and very beautiful, showed almost no expression.” Nina’s Sleeping Beauty is physically awake; her emotions (save rage) are deadened. In Rafael’s imagining, it will take more contact than a kiss to bring Nina back to life: “If Nina agrees to sleep with me, even once, he thought in all earnestness, her expressions will come back.” Rafi might picture himself as an overly forward Disney prince, but Grossman’s love story is pure Grimm. When Gili is three, Nina reenacts her mother’s abandonment by leaving Gili and Rafi. Instead of living happily ever after with husband and child, Nina disappears on a quest to be chosen, over and over again. The result is a life of emotional instability and sexual degradation. Her intermittent visits cause more harm than if she simply stayed away.

Grossman, a Man Booker–winning novelist, is also known for his political writing and his emphasis on the rights of the individual over the demands of the state. Doing press appearances for this latest novel, Grossman explained that he wanted to write it because he is “drawn to situations where the individual is facing total obtuseness, total brutality, and to see what happens to the individual: if he is able or she is able to remain herself under a total attempt to crush her identity or to give it another name or to impose another truth on it.” One wonders whether Gili is reflecting Vera’s influence or Grossman’s when, called on in school to recite a war poem by Haim Gouri at a Yom HaZikaron ceremony, she instead speaks a “mortally embarrassing private lamentation.”

But More Than I Love My Life is more than just a political commentary inside a psychological novel. When he gave the opening address at the International Literature Festival in Berlin in 2007, Grossman pointed out that non-Jews speak about the Holocaust in terms of “what happened then,” while Jews, regardless of the language they speak, talk about “what happened over there.” Then happened and ceased to happen. But there? “There . . . suggests that somewhere out there, in the distance, the thing that happened is still occurring.” The horrors over there, at Goli Otok, are still playing out in the damaged lives of Vera’s daughter and grand-daughter.

Although the novel sprang from Grossman’s friendship with Eva, it’s even more the story of Nina and Gili, the traumatized daughter and granddaughter, that will resonate with many readers. Few of us will ever have contact with a prisoner of conscience, while damaged family members are all around us. The gulag, even one the size of an archipelago, isn’t infinite, but our capacity to wound each other in the confines of our own homes is.

The island where Eva was imprisoned has been called the Alcatraz of the Adriatic. While both can be toured today, only Alcatraz is being physically maintained. Goli Otok is forever falling into greater disrepair but lives on in Gili’s mind, exactly as her grandmother described it to her:

I know Goli Otok as if I were born there. I could give guided tours of the place. For my roots project in seventh grade I made a card-stock model of the island. Anything else? My email address? [email protected].

Inevitably, the three women will travel back to that place to touch the thing that is still happening. Rafi goes along to film the trip, with Gili once again his script girl, writing it all down. And when they do, a curious thing happens in the book: all references to myths and fairy tales drop away as Grossman makes room for the possibility that patterns long set by trauma can find new forms. Goli Otok is where Gili can ask herself, “Who am I without hating Nina?”

On Grossman’s telling, Eva Panić was quite intentional in luring him, Scheherazade-style, into learning about her incredible life. She first called him about a piece he had written on the settler movement in an Israeli publication. As the conversation moved on, she told him a bit about herself, ending the call on a cliffhanger. It was a tactic she would repeat until he demanded to sit down with her and hear everything at once.

Early in their twenty-year friendship, Eva Panić asked Grossman to write her story, a request she would repeat over the years. Of course, Grossman was fascinated by her and wanted to agree, but the decision was a difficult one. In the years after she first broached the subject, he wrote other books—A Horse Walks into a Bar, Falling Out of Time, To the End of the Land. Even when writing Eva’s story felt, as he put it, “inevitable,” he nonetheless hesitated. He wanted to write it as fiction, to have the freedom to imagine and create, to explore Eva in a way he couldn’t in a work of nonfiction. “It is not easy to write a fiction story about a real flesh-and-blood human being,” he says:

At a certain point, you feel you need to protect this person from what you see. . . . All of us, we have this way to protect ourselves from the less attractive parts of our personality. And here comes the writer, and with very sharp intentions and eyes maybe makes all the hidden weaknesses surface. It can be painful.

The result will indeed hold painful moments for the reader. Eva, however, never read Grossman’s novel. It was published in Israel shortly after her death in 2015. And it’s unclear if she was ever able to see, much less take responsibility for, the human costs of her principled stand not to denounce her husband no matter what it would do to her daughter. But Gili imagines it for us, showing what might have happened had Grossman intruded on Eva’s memories during her life:

At that moment I see what I’ve already seen more than once when shooting documentaries: something ordinary, prosaic, which someone says on camera . . . hits them as if they were hearing it for the first time, and the story they’ve been telling themselves for years shatters.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

Love and War

David Grossman has for sometime been one of Israel's most talented and important writers. In many of his novels, his feeling for adolescence—one is tempted to say, his identification with it—has been so brilliantly intuitive that the imagining of adulthood has scarcely been possible. In To the End of the Land, Grossman makes his breakthrough.

Equine Ambles into a Watering Hole: An Interview with Jessica Cohen

An interview with Jessica Cohen—winner of the 2017 Man-Booker International prize for her translation of David Grossman’s Horse Walks Into a Bar—on translating Hebrew literature and jokes.

“A Story of Commitment, Solidarity, Love Even”

Retracing her father’s wartime journey from Poland, across the USSR, through Iran and eventually to Palestine, Michal Dekel learns a lot about what it means to belong to a people.

History of a Passé Future

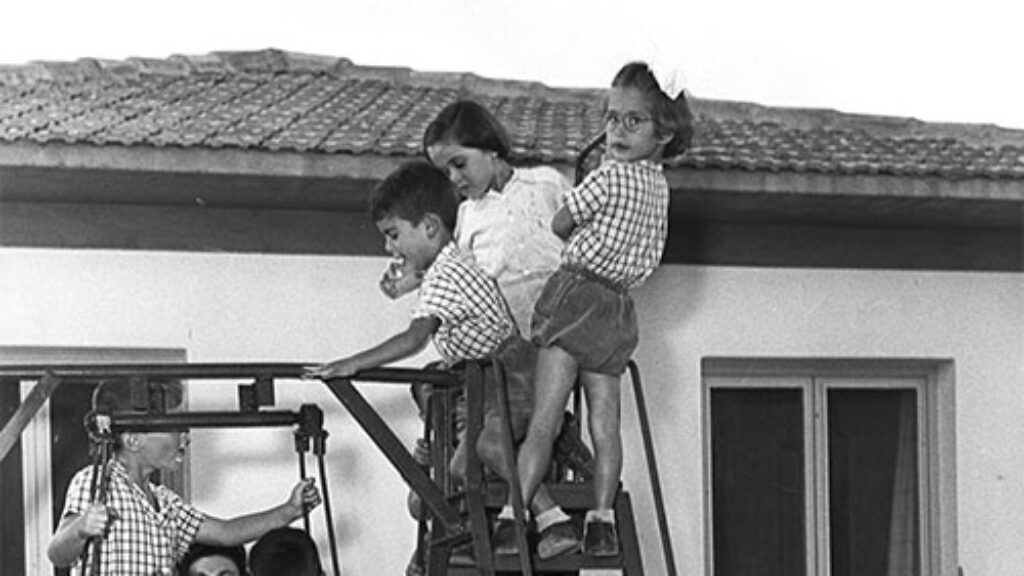

At their inception, the children’s house and collective education were to shape a new kind of emotionally healthy person unfettered by the crippling bonds of the traditional or bourgeois Jewish family. Over the last two decades or so, a cultural backlash has set in among some of those raised in children’s houses.

Judith Samuel

Thank you for your review of David Grossman's story of Eva. I began my subscription to The Jewish Review of Books today. A good way to begin a New Year, I think!

Sincerely,

Judith Samuel