Confirmed as Drowned

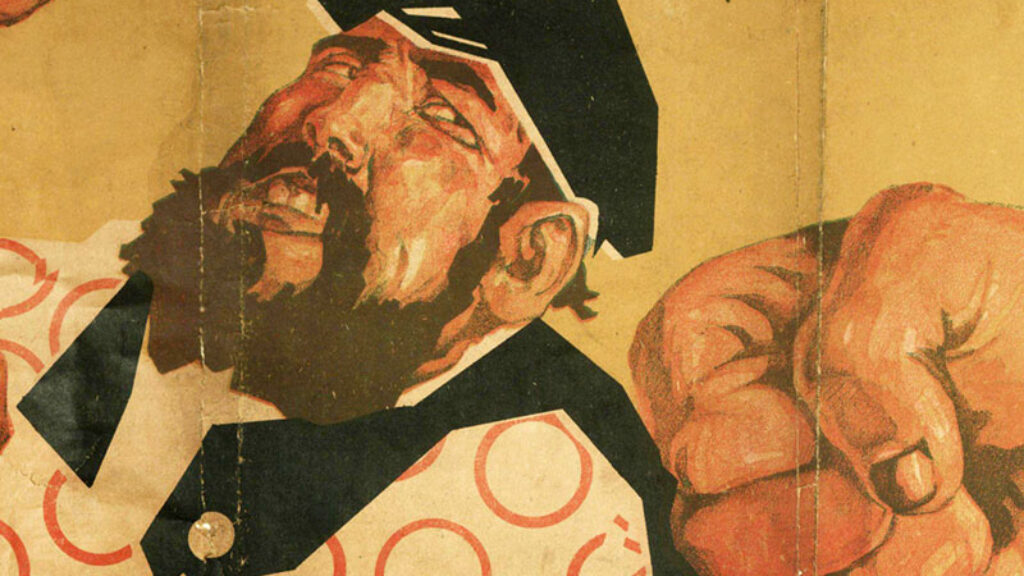

On December 14, 1906, a cargo steamship built at the Sunderland shipyards in the northeast of England was launched under the name Holywood. She was then purchased by a Greek shipowner in 1935, who renamed her Tanais, after the ancient Greek colony founded by Milesians. On May 26, 1941, during the Battle of Crete, the ship was sunk by the Luftwaffe, only to be raised and repaired by the Germans, who then deployed her as a cargo ship in the Aegean. In early June, the Nazis filled the holds of the ship with about nine hundred prisoners bound for Auschwitz, among them Cretan partisans, Italian prisoners of war, and the entire Jewish community of Crete, which comprised 299 souls, 88 of them children.

On June 9, the Tanais was torpedoed by the British submarine Vivid, killing all but a handful of passengers. This was the end of the Cretan Jewish community, which had thrived on the island for more than two thousand years. (Jews are said to have served as guards at the palace of Knossos, where King Minos had Daedalus build the labyrinth with his son the Minotaur at its center.)

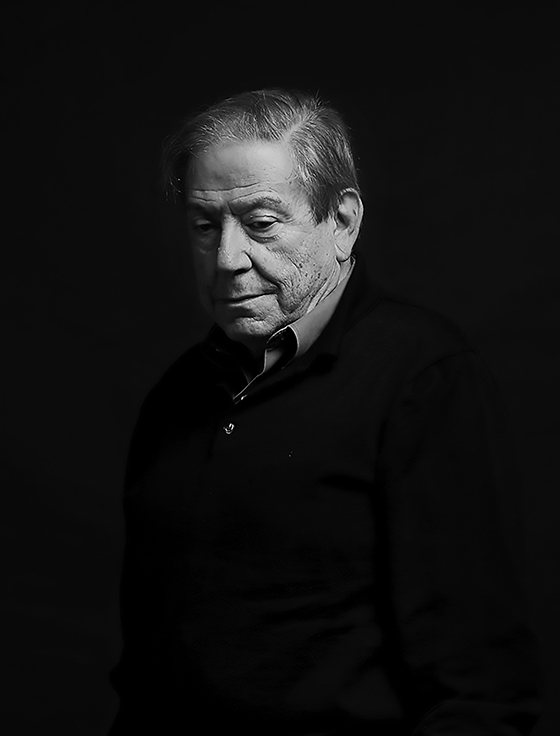

The poet Iossif Ventouras is now the only living Jewish male born in Crete. “All that remains of the Jewish community of Crete is a very old synagogue—a Venetian building—that bears the Hebrew name Etz Hayyim. . . . This ‘tree of life’ is orphaned now, as all its children were lost,” he told Adam J. Goldwyn in an interview. Ventouras—the family name is thought to have started life as Ben Torah—was born in the Cretan city Chania in 1938. His family, like many of the Jewish community of Crete, was of Venetian descent. They escaped the island after a friend warned his father that “things would not go well for the Jews,” fleeing to Athens on a fishing boat.

In a 2009 poem called “Kyklonia,” (modern Greek for “cyclone,” but also an allusion to the poisonous Zyklon B used to murder Jews at Auschwitz and elsewhere) Ventouras writes elliptically of his family’s escape from Crete:

Ten

Ten steps

the sea

With two oarsand two sails

they counted

Omens

in heaps of carob beans

Soon after arriving in Athens, the family was betrayed by Nazi sympathizers and had to go into hiding. Iossif was separated from his mother and cared for by a nanny. Although the nanny, who was named Athina, was devoted to Ventouras, the separation was traumatic and confusing to him. In “Kyklonia,” he quotes some personally resonant lines from the great Holocaust poet Nelly Sachs:

My mother held me by the hand

Then someone raised the knife of parting.

Although he had been reading and writing poetry his entire life, Ventouras’s first poetry collection, Ygros Kiklos (Liquid Circle) did not appear until 1997, when he was almost sixty. Four years later, he published “Tanais,” the title poem of this volume, and, eight years after that, “Kyklonia.” It had taken him more than half a century to write about the war, as he did in “Tanais”:

pedlar of spasms in my stammering tongue

How shall I utter dystocic consonants

The Greek word “dystocic,” which is occasionally also used in English, means “to give birth with difficulty.” Before writing the poem, he returned to Crete, visiting the old neighborhoods in Chania and the house where he was born.

“Tanais” and “Kyklonia” are, I believe, two of the most important and devastating poems written in the wake of the Holocaust, and they are now finally available in an English translation in this volume from the small publisher Red Heifer Press.

In A. B. Yehoshua’s novel, Mr. Mani, a Jew-hunting soldier named Egon Brunner is intoxicated by Crete and the ruins of Knossos where his Jewish target, Mr. Mani, is a tour guide. “Crete, this most wonderful place that has been from the start . . . the true grail of our German soul,” he declares. But where Yehoshua’s Nazi celebrates a fabricated connection between German and ancient Greek culture, Ventouras is a true heir to two ancient traditions, Jerusalem and Athens. In “Kyklonia,” he writes:

‘Question: what is your name?’

‘Answer: My Jewish name, or . . . ? My Greek name is . . .’

The poemopens with an epigraph from Jeremiah (1:13): “I see a bubbling pot / and its spout is facing north,” which the poet adopts as a description of the German invasion of Greece and Crete. Ventouras’s other great Holocaust poem, “Tanais,” opens with Homer:

There do thou beach thy ship by the eddying Oceanus,

but go thyself to the dark house of Hades.

These are the words of the sorceress Kirke from Book Ten of The Odyssey. And Odysseus will go down to Hades to encounter the spirits of those he has fought alongside at Troy. Ventouras continues his poem with the names of all eighty-eight children who were drowned and then revisits them in the empty Chania streets where they once played together on Purim:

and you Esther were a child

a child dressed in a queen’s costumeyou wore a paper crown and threw confetti

and Baba brought Haman’s teeth to the feast

Estherwithout a compass and

the bodies freeze

your hair will take the color of seaweed.

Ventouras frequently invokes the names of the children who drowned, both memorializing them and dramatizing their tragedy:

into the mikvah

would descend

Victoria Rosa and Leah

waterplants in the seaunannounced

bloodless

Among Ventouras’s publications is a still-untranslated work of prose, Ibbur: The Jews of Crete 1900-1950. “Ibbur,” Ventouras explains, “denotes the state of a dead soul that migrates to a living person to perform a task.” On a number of occasions, he has claimed that he felt possessed while writing the poem. “I often felt my hand being led into writing by someone else as if it were, in a way, an automatic writing.” His lines often take on an incantatory feeling:

If you look into the night

you see my nights

they sow grey scales and rust

they corrode the sarcophagi of the deep . . .

if you look into the night you see geniesthey seal the bones of children in chambers of steel.

Ventouras draws his reader into the world he reimagines with arresting, graphic images:

I was walking a tightrope

for whatever glows

when sunlight curved

towards the abyss

and then back again

where I arose a tree trunk

His lyric voice also lends itself naturally to music. The Cretan composer Marielli Sfakianaki has written a powerful cantata, setting verses from “Tanais”.

In her introduction to this volume, Elisabeth Arseniou describes the poem as “replete with meaning, reversals (overturning, capsizing) silences and absences. Missing letters, cracked images, blurred faces.” Ventouras writes in “Tanais.”

fissures in narrations

wings of birds

broken vowels

ι ι ο ο α α ε ε υ υ

ουαι αει alas forever

He roots his poem in a long Greek tradition with words from the ancient language, while at the same time evoking the shattering of a world that will never be restored.Ventouras, like Odysseus, survived, but he is harrowed by guilt. He writes:

I returned . . .

here are the taxes we pay,

yet

It would have been a meddlingto let the scar heal.

Although the prescience of his family allowed them to escape Crete, in his poem Ventouras declares:

I am here

confirmed as drowned.

Ventouras has acknowledged the influence of modern Greek poets, including Odysseus Elytis (winner of the 1979 Nobel Prize for Literature) and Giorgos Seferis, but has claimed that “for the two elegies . . . I was taught by Paul Celan.” In a Zoom chat, Ventouras plunges to one side of his desk and reappears with a pile of books by Celan in parallel Greek-German editions. Foremost among them, for him, is the collection Die Niemandsrose, in a version by Christos Lazos, whom he describes enthusiastically as “a genius translator. I don’t know German, but I can smell the translation, how it is done. Very, very good.”

Die Niemandsrose is the collection in which Celan draws most frequently on Jewish themes, but though Ventouras’s work is also peppered with Jewish scriptural references, he is drawn to Celan especially because “his poetry is like a broken language. Like a person who suffers and articulates words that come out of his pain and problems.”

In places, the powerful imagery of Ventouras’s Greek recalls the early Celan of the famous “Death Fugue.” Take these lines, for instance, from “Kyklonia”:

Nobody noticed the flesh

kissing the chimneys on the mouth

These are more shocking still than Celan’s famous image (in John Felstiner’s translation): “You’ll rise up as smoke to the sky / you’ll then have a grave in the clouds where you won’t lie too cramped.” The concluding lines of the opening verse of “Kyklonia” read:

and his word was a wound

and his wound a word

This reminds one of Celan’s claim that he was “Wirklichkeitswund und Wirklichkeit suchend” (wounded by reality and seeking reality). Yet, Ventouras’s Holocaust poetry, particularly “Tanais,” contains an optimism not found in Celan. Witness that poem’s concluding apothesosis:

in a cup I will gaze into the future

faint footprints of shapes that will return

ethereal and winged will descend

dressed in clothes

on weird machines that travel . . .

salt is lifegrains of salt.

Ventouras also evokes the everyday lives of the Cretan Jewish community in passages that are laden with tragic irony:

Sereno whistling down Kondylaki Street

the Eve of Sabbath and Olga

would be dressed

in Florentine lace

the Bride cometh

and he has longed for Her warmth

Her blessing spreadeth through the neighbourhood

. . . vayekadesh oto ki vo shavat mikol melachto

Olga, who was once Sereno’s Sabbath Bride, has drowned.

Having subjected himself to the experience of the children drowning in “Tanais,” in “Kyklonia,” Ventouras uses an acrostic of the Greek alphabet to frame an unflinching description of the gas chambers:

What darkness

Sound of blood clotting

Clotting choking

Scaffold upon scaffold

And they totter Kyrie

They melt . . .

UnearthlyChyrysalides

They are baking

I chant Kyrie

I howl

It is interesting that Ventouras chooses to “chant Kyrie” rather than invoking one of the Jewish names for God. Kyrie eleison is the Septuagint’s rendition of

Haneini Adonai (Lord, have mercy) in Psalms and is commonly used in Christian liturgy. It is as if, at this moment of particular horror, he is impelled to draw on elements from all the cultures into which he has been born.

“Kyklonia” concludes by invoking the great seventh-century Byzantine Jewish poet:

I chant your hymns Eleazar ben Killir

You have forsaken us Kyrie and the soul cries out in agony

No one translator is identified on the title page of this volume. In his Acknowledgments, Ventouras recognizes a number of versions and concludes by expressing his “gratitude to my publisher, Peter Gimpel, for his enthusiastic support of this project and his meticulous care in editing the English text.” Anglophone readers certainly have every reason to be grateful to Gimpel and Red Heifer Press for making this important Greek Jewish voice accessible. But earlier, unpublished translations I have seen of “Tanais” by Elisabeth Arseniou and “Kyklonia” by Helen Dimos and Giannis Goumas, which were apparently the basis for the translations in this volume, suggest that there has been considerable and rather inartful meddling from the publisher-poet Peter Gimpel. Even an indubitably great poet such as Ventouras, with a nose for translation, can sometimes be led astray in another language, and I am very much afraid that this may have been the case with Ventouras here.

Thus, following a list of the Cretan Jewish children murdered by the Nazis, Ventouras opens his poem: “Me-sto-ma igro / Nero-ponti / To fyllo-ma pnigmeno.” In her unpublished translation, upon which the published version in this volume is apparently based, Arseniou sensitively renders this as:

In-flu-ent mouth

down-pour

the foli-age drowned

But in the book, we read:

With gushing mouth

waters in flood

the foliage but drowned

The missed hyphenation, which Arseniou keeps, is crucial, retaining the gaps that, as Arseniou has explained in her introduction, are key, particularly at the start of the poem. One can go further. The Greek nero-ponti, which in the book is rendered, “waters in flood,” Arseniou correctly translates as “down-pour,” again retaining Ventouras’s hyphenation and using one word instead of three, while the redundant conjunction “but” in the book version’s third line lends Ventouras’s poetry an unneeded, archaic quality. Elsewhere, the book renders I foni katakleinei / astheniki pou vythidzetai / anatolika tou pelagou as:

the voice fades

asthenic plunges

into the Aegean

Why translate “astheniki” with the obscure English medical term “asthenic”? Arseniou’s “infirm” renders the Greek accurately and comprehensibly.

Peter Gimpel ought to have let the great poet’s voice fade and plunge without interference or embroidery. For now, however, this is the Ventouras that English readers have, and there is much here for which to be grateful.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

Bread and Vodka

Mendel Osherowitch's 1933 book about life in Ukraine not only bore rare eyewitness testimony to one of the worst atrocities in a barbarous century; it did so from the vantage point of a brother of two of the perpetrators.

The Poet from Vilna

Avrom Sutzkever and Max Weinreich, a memoir.

Back in the USSR

On the ephemeral nature of home and “certificates of cowlessness” in Russia's Jewish Autonomous Region.

Intense Listening: The Poetry of Harvey Shapiro

Harvey Shapiro, who grew up in an observant Jewish family, was a connoisseur of distances and silences.

Dennis Gura

With respect, a minor correction: Kostas Papadopoulos by his own account was born to a Jewish mother, and a Greek Orthodox father, on Crete in 1942, and survived the war there. I had the honor of spending a long afternoon in Mr Papadopoulos’ shop in Heraklion in ‘17. Unless Mr Papadopoulos has passed away, Mr Ventouras is not the sole living Jewish male born in Crete.