Nothing but Literature

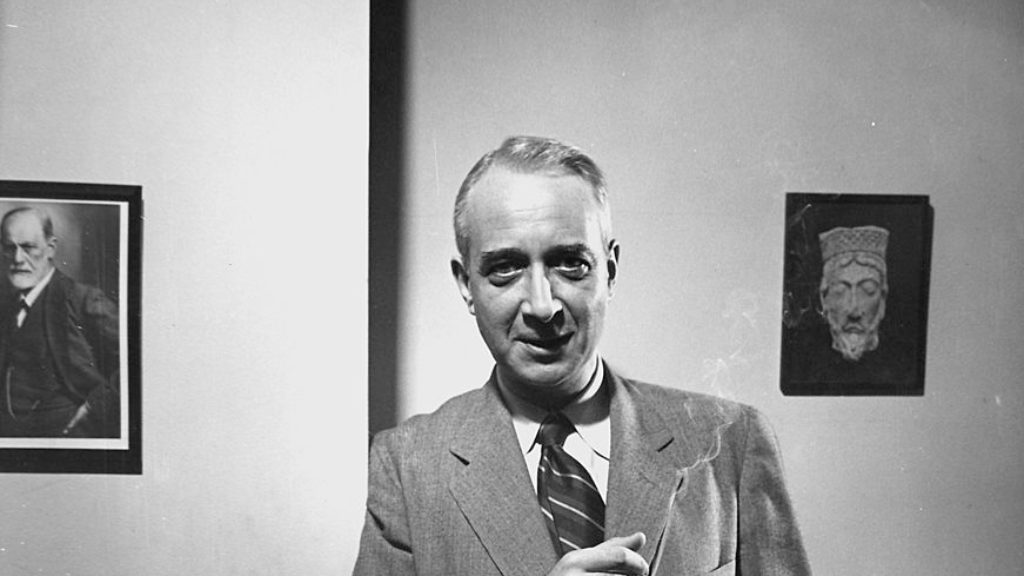

Max Brod, Kafka’s close friend in Prague and his literary executor, is both famous and notorious for what he did with Kafka’s Nachlass. Famously, he did not follow Kafka’s instructions to burn all his unpublished writing, and so Brod saved for posterity one of the paramount treasures of twentieth-century literature. Notoriously, he saw fit to edit the work aggressively, manipulating the chapter order in the unfinished manuscripts, regularizing the style according to his own rather conventional literary lights. (Walter Benjamin remarked that of all the puzzles around Kafka, one the greatest was his friendship with Brod.) The diaries were the texts that suffered most, as Ross Benjamin explains in the introduction to his admirable translation, which includes more than fourteen hundred scrupulously researched, helpful endnotes. Brod was wedded to the idea that his friend should appear to the world in proper German, and so he presumed to regularize Kafka’s somewhat idiosyncratic language and punctuation, to paper over the fragmentary nature of the diary style, and to tone down or eliminate many of the sexual references. An unexpurgated version of the German text appeared in 1990. It is perhaps not surprising that more than three decades passed before any English version, given the massive amount of work involved in doing the job right, as Benjamin has impressively done.

What purpose did these diaries serve for Kafka? Writing them was clearly very important to him. At one point he exhorts himself: “Hold fast to the diary from today on! Write regularly! Don’t give up! Even if no salvation comes, I want to be worthy of it at every moment.” Salvation is surely a peculiar hope to invest in a diary. The one that Kafka produced incorporates many of the things one would find in an ordinary diary—transcriptions of the day’s experience, conversations with friends, the report of theatrical performances seen, descriptions of oddities or eye-catching sights chanced upon in the public domain. But it is also an instrument of self-knowledge for this harrowingly introspective writer as well as a laboratory for his fiction. There are dozens of false starts of stories, some just a sentence or two, typically a paragraph or a few pages. Much of the first chapter of The Lost Person (renamed Amerika by Max Brod) and all of “The Judgment” were initially diary entries. Kafka’s perfectionism is repeatedly evident: occasionally, even a prosaic observation undergoes two or three revisions. Alongside the revisions are declarations about the faults of the writing and the difficulty of the task. Again and again we encounter such entries as “nothing today” or “nothing written for three days” or pronouncements about the wretchedness of what has been written:

That I’ve put aside and crossed out so much, indeed almost everything I’ve written this year, that definitely also hinders me a great deal from writing. Indeed, it’s a mountain, it’s 5 times as much as I have ever written and by its mass alone it pulls everything I write away from under my pen to itself.

Like Agnon and Babel, Kafka was an admirer and in a way a disciple of Flaubert, but in contrast to the indefatigable French reviser he was acutely tormented by his perfectionism as he was by much else in his life—his family, his job, his body, sex, his condition as a bachelor.

Even a hypochondriac can fall ill, and long before the onset of the tuberculosis that would end his life at the age of forty, he was constantly listening to his body, finely tuned in to pick up any sign of breakdown. He was assailed by everyday complaints: headaches, chills, digestive ailments, severe insomnia. Since Kafka was an original, even his kvetching shows a certain originality of perception: “How far from me, for example, my arm muscles are.” There are abundant entries like the following:

But now I’m lying here on the sofa, kicked out of the world, waiting intently for the sleep that refuses to come and when it comes will only graze me, my joints are sore with fatigue, my scrawny body is trembling to its ruin in agitations, of which it must not become clearly aware, my head is throbbing to an astonishing degree.

Kafka would have felt isolated from people and the world even if he had been granted the body of an Olympic athlete, but his persistent sense of physical frailty and aches and pains surely reinforced his sense of being condemned to isolation.

All this, of course, is well-known, not only through the voluminous scholarship, biographical and otherwise, that has been devoted to Kafka but also because his extravagant neurosis, his image as a tormented soul, has entered the popular culture.

What, then, do the diaries add to our understanding of Kafka? Perhaps not that much in substance but a great deal in revelatory degree. In 1910, immersed in an effort to finish “Description of a Struggle,” he writes, “I won’t let myself get tired. I will jump into my novella even if it should cut up my face.” The diaries are punctuated by such notes of violence and physical wounding: “The tremendous world I have in my head. But how to free myself and free it without being torn to pieces.” There is a direct transition from self to fiction, as in this sentence put down for possible inclusion in his story “In the Penal Colony”: “And even if everything was unchanged, the spike was still there, crookedly jutting out of his shattered forehead.”

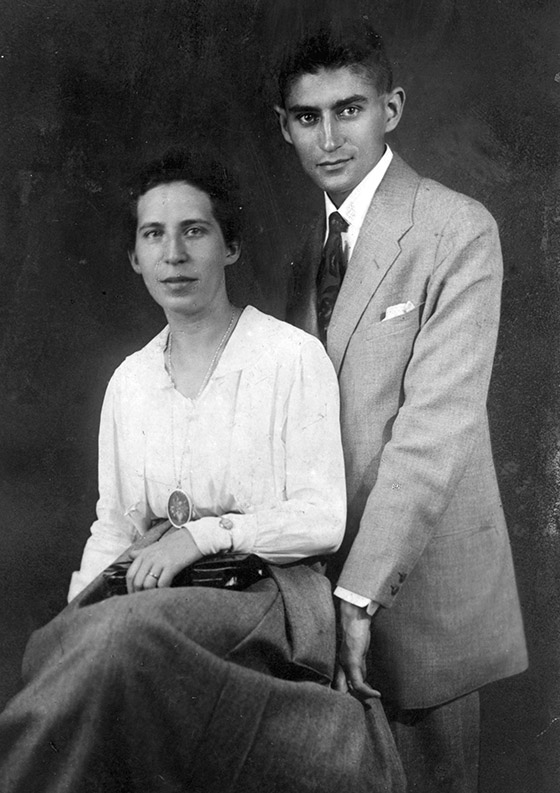

Kafka often experiences writing itself as something dangerous, something that could lacerate him or pull him apart. In an entry with a somewhat generalized reference to what he calls “the negative,” he speaks of a self-defensive instinct against it “that doesn’t tolerate the production of the slightest lasting contentment for me and, for example, smashes the marriage bed before it is even set up.” In introducing the marriage bed as his example, he is surely thinking of his on-again, off-again engagement to Felice Bauer, for him more a daunting project than a planned union of love, and which predictably ended in failure. What is arresting is the violent image of smashing the marriage bed, the bed that is a symbol of the institution of marriage and also, pointedly, of sexual consummation in marriage, which in all likelihood was an intimacy never realized with Felice Bauer.

Altogether, the diaries give us aspects of Kafka’s life more or less known but expressed with a jolting extremity. His often observed sense, for example, of his work at the state insurance company as drudgery comes across here as a hellish experience that is tearing him apart: “Here in the office for the sake of so wretched a document I must rob a body capable of such happiness [in writing] of a piece of its flesh.” The diaries are punctuated with disturbing entries on the fear of insanity, contemplations of suicide, and masochistic fantasies: “This morning for the first time in a long while the pleasure again in imagining a knife twisted in my heart.” The connection with Joseph K.’s execution by stabbing at the end of The Trial and the diabolic execution machine of “In the Penal Colony,” and with various hideous deaths in some of the stories, is all too clear.

Kafka was a master of ambivalence. The three principal topics of ambivalence in the diaries are Judaism and Jewish culture, the institution of marriage, and sex. It may surprise some that of the three, the subject on which he was least ambivalent was Judaism. Raised in a thoroughly secular German-speaking home, he intermittently saw Jewish religion and culture as offering an authenticity of which he had been deprived by his upbringing. He reports being deeply moved at a Kol Nidre service, though, unlike Franz Rosenzweig’s parallel experience, it was not part of a personal transformation. He read Graetz’s history of the Jews and a history of Yiddish literature and repeatedly flirted with Zionism, at one point even briefly contemplating the possibility of immigrating to Palestine.

The major focus of the allure he felt in Jewish culture was the Yiddish theater that located for a run in Prague in 1911–1912. The bulk of the entries for this period are devoted to that theater. He went to performances night after night, scrupulously recording the plots of the plays and the gestures and appearance of the actors. He became infatuated with one of them, Mania Tschisik, and he gave considerable attention to her looks and the figure she cut on stage. Her husband was also a member of the troupe, and Kafka’s relationship with her did not go beyond infatuation. His attachment to the Yiddish theater is a vivid instance of a recurring phenomenon of the time in which young German or German-speaking Jews from assimilated backgrounds (Rosenzweig, Scholem) were drawn to the world of Ostjuden as a manifestation of natural cultural vibrancy and unselfconscious Jewishness that they lacked. Kafka observes that the Eastern European Jews were “people who are Jews in an especially pure form, because they live only in the religion but live in it without effort, understanding or misery.”

The Yiddish plays he attended were magnetic for him, though of course he recognized that the plots were sensationalistic, sentimental, and contrived, and the theater was kitsch. He became increasingly aware that this was a cultural heritage, however much it had drawn him, which he could scarcely embrace:

My susceptibility to the Jewishness in these plays abandons me, because they are too monotonous and degenerate into a wailing that is proud of isolated stronger outbursts. At the first plays I could think I had come upon a Judaism in which the beginnings of my own would rest and would develop toward me and thereby enlighten me and bring me farther in my ponderous Judaism, instead the more I hear, the more they recede from me.

Kafka’s ambivalence about his “ponderous Judaism” is the consequence of an insoluble dilemma of identities. He could scarcely think of himself as Czech, and though German was his primary language, he would never have imagined himself in any sense as German. The mixed messages about Judaism he got from his parents left him in a state of confusion. Jewish peoplehood, embodied in the Jews from Eastern Europe, exerted a strong pull. In the sentence after the diary entry I have just quoted, he writes, “The people remain, of course, and I cling to them.” Perhaps we should think of this as someone clinging to a life raft—he clings but he can’t get on the boat. The flip side of his attraction to Jewish peoplehood comes out in a succinct entry later in the diary that has often been quoted, for good reason: “What do I have in common with Jews? I have scarcely anything in common with myself and should stand completely silent in a corner, content that I can breathe.”

Kafka’s ambivalence about marriage follows directly from his feelings about his home, presided over by the dominant father who haunted him all his life. Although what he most wanted to do in the world was to be left alone to write, being a bachelor made him repeatedly uneasy. What a mature, independent man was supposed to do, after all, was to marry, establish a proper bourgeois home, and produce children. He knew this is what the culture, and of course his parents, expected of him, but he doubted that he would ever be capable of doing it.

It was this ambivalence that manifested itself so painfully in his never-implemented proposal of marriage with Felice Bauer. Whether he felt anything one could call romantic love for her is unclear. Bauer possessed all of the required credentials—she was a proper young Jewish woman of good family (though her brother would turn out to be an embezzler who had to flee the country) and also a modern independent woman with a job, a role often questioned in that era but not by Kafka. And, evidently, she was someone open to joining her fate with a man for whom, as he affirms in his diaries, literature was everything. The fact that she was in Berlin and he was in Prague helped nurture the doomed idea they shared of living together as man and wife. They were able to see each other only intermittently while communicating through frequent letters. Any fantasies each may have had about the other could be cultivated as well as any misunderstandings in this tense relationship of absences. Only one of their infrequent meetings, at Marienbad, went well, but it didn’t solve any of their problems.

In his diary, Kafka admits that what he feels for Felice cannot be called love: “With F. [Felice] I never had, except in letters, the sweetness of the relationship to a beloved woman as in Zuckmantel and Riva, only boundless admiration, subservience, sympathy, despair and self-contempt.” Zuckmantel was the location of a sanatorium where during his stays there in 1905 and 1906 he had an affair with a woman about whom nothing is known. Riva was the site of another sanatorium where in 1913 Kafka was involved with an eighteen-year-old young woman indicated in the diaries only by her initials, G. W. It is obvious that during his convalescences in various sanatoria he did more than lie in a chaise lounge sipping salubrious drinks.

Kafka may have been tormented and monastic, but he was far from the literary monk of popular imagination. In any case, the two women in question and a good many others shared with him what Felice Bauer could not. Rather, she was the avatar of the idea of marriage to which he ambivalently aspired rather than a flesh-and-blood object of desire for him. But the actuality of marriage, given the oppressive weight of his family of origins, was simply too fraught for him. And for the women with whom he was intimate, the intimacy had its limits.One of the saddest sentences in the diaries is an entry from 1922, not long before his death: “I have lovers but I cannot love.” Kafka, always harsh in his judgment of himself, may not be entirely fair here to his experience with three different women late in his life, two that had recently ended and another about to occur.

Because references to sex were what suffered most from Max Brod’s interventions, this finally available unexpurgated text gives English readers a fuller sense of Kafka’s sexuality than they have had till now. In the course of the 566 pages of diary entries, there are two that definitely seem to be homoerotic. One of these two entries is when he notices the shapely legs of beautiful Swedish boys at a beach and has a fantasy of running his tongue along the legs. This startling flight of fancy is hardly the sole instance of his giving free rein to wild fantasies in the diaries. The other instance is his noticing the bulge in the crotch of a male passenger on a train. That, however, is part of a rather matter-of-fact cataloging of aspects of the person’s appearance as it meets the eye, something he does quite often in his diary observations of people, and in context it does not have much of an erotic charge. A decade ago, the historian Saul Friedlander seized upon these entries to argue that they offered the key to understanding Kafka’s ambivalent life. Now that the passages are available in English, predictably, several American reviewers have followed him. But Kafka’s leading biographer Reiner Stach has already suggested a more nuanced approach: “He had a really intense access to his own subconscious, more than we might have, and this is why he is such a great writer. So, he had homosexual, bisexual, sadistic, masochistic and voyeuristic fantasies. . . . But you can’t conclude that he was any one of those things himself.”

In any case, all of the other sexual remarks in the diary, of which there are many, are about women. Kafka was an inveterate girl-watcher, even in the later years of his short life when he was ill. There are recurring entries such as the following, from a travel diary: “The girl whose belly while she was sitting was without doubt unshapely over and between her outspread legs under her translucent dress, whereas when she stood up it dissipated like theater scenery behind veils and formed an ultimately tolerable girl’s belly.” Or more succinctly: “The torso: seen from the side from the upper edge of the stocking upward knee, thigh and hip, belonging to a dark woman.” But Kafka, being who he is, interrogates his proclivity to check out attractive women: “What connects you to these firmly bounded, speaking, eye-flashing bodies more closely than to anything, say, the penholder in your hand? That you are of their kind, perhaps? But you are not of their kind, indeed that’s why you raised this question.”

Kafka did not confine himself to merely voyeuristic excitements. At one point in 1916, he counts at least six “aberrations with girls” during a limited time-span. Characteristically, these involvements brought him not satisfaction but remorse. In another of his violent images, he writes, “It positively tears my tongue out of my mouth when I don’t yield to admire an admirable one and love her until the admiration (which indeed comes flying) is exhausted. Toward all six I have almost only inner guilt, but one of them had someone reproach me.”

Not only was sexual gratification fraught with guilt for Kafka, but he also assumed that “admiration” and love were transient and would inevitably be exhausted. In addition to his sexual roaming, Kafka, as has long been known, was a frequent patron of brothels. There is even one entry that includes a detailed description of a brothel and the deployment of women within it. As one would have guessed, he came away from the prostitutes with the same bleak feelings he experienced after being with his episodic lovers.

Late in his short life, he had three more serious involvements, first with Julie Wohryzek, whom he met in a rural setting where both were convalescing, then with Milena Pollak, a married Czech journalist who was a rather wild young woman, and finally with Dora Diamant, who had fled her Eastern European Hasidic family for a freer life. Diamant is not mentioned in the diaries because she came into his life too late to be included; Pollak appears with some frequency, usually designated as M., though he does not include any erotic representation. However, Kafka felt sufficient intimacy with her to entrust her with the notebooks of his diaries. They talked of moving in together, but, given his ambivalence, that never happened. He and Julie Wohryzek planned to marry, but he pulled out at the last moment, chuppah-shy as always.

Kafka and Dora Diamant shared an apartment—the first time he ever lived with a woman—in a tree-lined suburb of Berlin during 1923, the last full year of his life. This union of a gravely ill forty-year-old and a woman of twenty-five might seem improbable, but as Reiner Stach observes, “It turned out to be a remarkably happy setup.” So Kafka, as the end drew near, finally enjoyed the conjunction of peaceful domesticity and love that had eluded him all his life—until he became too ill to enjoy anything. Nothing is known about the sexual aspect, if there was one, of his relationship with Dora Diamant or Milena Pollak, though Max Brod in his own diary describes the latter as “a great passion.” But the evidence of the diaries shows that at least until these three late loves, sex was a constant part of his life that repeatedly impelled him and deeply troubled him.

In an entry written in 1922, which was during his involvement with Milena Pollak, Kafka writes:

s. presses me, torments me day and night, I would have to overcome fear and shame and probably even sorrow to satisfy it, but on the other hand it is certain that if an opportunity presented itself quickly and attainably and willingly, I would immediately take advantage of it without fear and sorrow and shame.

The “s.” at the beginning of this excerpt is Ross Benjamin’s equivalent for the initial G. in the German text, which he persuasively proposes is an indication of Geschlecht, the German word for “sex.” Kafka, who had no compunction about freely engaging in sex, seemed uneasy about writing out the word in the diary. This may have been a reflex of his unsuccessful effort through most of his life to realize sexual gratification in a way that did not leave a sour aftertaste of guilt. Perhaps this is something he finally achieved with Dora Diamant, if he was not too ill. In any case, in those final months he had the contentment of being with a good woman who loved him and was prepared to look after all his needs.

The publication of a diary inescapably leads one to peek into the hidden places of the diarist’s life, an act that carries with it a certain sense of voyeurism. But, as Kafka announced more than once, he was nothing but literature, and his diaries, for all the intimate revelations they contain, are also nothing but literature. He had set out to find salvation in writing the diaries. That was not only because he used them as a testing ground for his writing—everything, after all, was a testing ground for his writing. Though it would be quite misguided to see his fiction as autobiographical, he certainly created it out of the roiling magma of his inner life. The violent images of that life which from time to time erupted in the diaries would reappear, transformed, in his stories and novels. The sense of despair recorded in these notebooks, the torture to which his own body subjected him that he repeatedly described in the diaries, the painful isolation from which he could not free himself—all became part of the imaginative texture of the utterly original fiction that he produced.

Writing in 1912, a pivotal year for him, after a sleepless night, Kafka noted in his diary, “The confirmed conviction that with my novel writing I am in disgraceful lowlands of writing. Only in this way can writing be done, only with such cohesion, with such complete opening of the body and the soul.” Most writers have not conceived their vocation in this way, but it is Kafka’s complete opening of body and soul that makes his fiction so hypnotically compelling.

A similar opening up can be felt in page after page of Kafka’s diaries. Reading them is more than peering into the cupboards of a private life. On the contrary, in his introspection and his friendships, in his frustrations of sex and love, in his travels, in his often arresting observations of the quotidian, one sees a great writer struggling with himself and the world and working to fashion a unique kind of art out of that struggle.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

Kafka at Bedtime

Kafka continues to interest everyone from academics to Hasidic slam poets.

Misreading Kafka

The Kafka myths, and the "myth-busters" who make them.

Distant Cousins

None of these four novels by American Jewish writers is fully at home in Israel—they’re more like Mars orbiters than rovers.

Man of Letters

Adam Kirsch’s judicious selection of Lionel Trilling’s letters throws instructive light on both Trilling’s life and American intellectual culture from the 1920s to the 1970s.

gershon hepner

THE AMBIVALENCE OF KAFKA AND HAMLET

With his inability of getting out from under

his father or his job, Kafka came to blunder

like Hamlet, while the voice of his old father’s ghost

was as improbable, his trial his innermost

reflections on his guilt, just like the ghostly voice

that Hamlet claimed to hear. Neither had a choice,

both motivated by the doubts about their guilt

they wished that they could feel, and caused them both to wilt,

because though their observers feel that they are in-

nocent, they’re overwhelmed by a sense of sin.

Like Kafka, who believes that he’s become a cockroach, Ham-

let turns into his father’s ghost, a hologram,

and we’re like them both of them when we can’t find a way

to make the sense of being guilty go away.

The two protagonists’ alleged equivalence

included towards both their lives a strange ambivalence,

a Leitmotif highlighting how much they are equal,

to “To be or not to be” The Trial Kafka’s sequel.

Robert Alter, reviewing The Diaries of Franz Kafka by Franz Kafka, translated by Ross Benjamin, writes:

Kafka was a master of ambivalence. The three principal topics of ambivalence in the diaries are Judaism and Jewish culture, the institution of marriage, and sex. It may surprise some that of the three, the subject on which he was least ambivalent was Judaism. Raised in a thoroughly secular German-speaking home, he intermittently saw Jewish religion and culture as offering an authenticity of which he had been deprived by his upbringing. He reports being deeply moved at a Kol Nidre service, though, unlike Franz Rosenzweig’s parallel experience, it was not part of a personal transformation. He read Graetz’s history of the Jews and a history of Yiddish literature and repeatedly flirted with Zionism, at one point even briefly contemplating the possibility of immigrating to Palestine….