Kafka at Bedtime

Franz Kafka’s greatest paradox—and that is saying a lot—may be that such a singular writer, who spent so much of his time trapped inside of himself, has ended up so profoundly affecting so many generations of readers. This popularity has resulted in both a century-long torrent of critical literature and a fair number of adaptations and retellings.

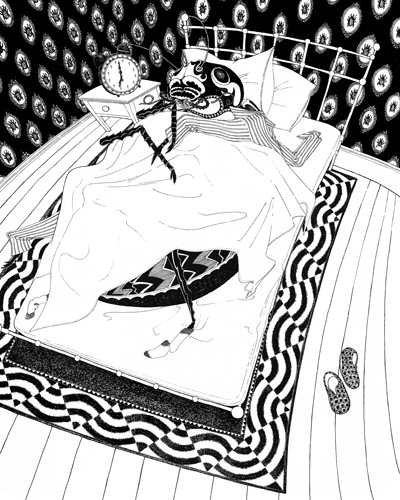

Two recent offerings in these genres demonstrate how Kafka continues to captivate readers both in and out of academia—in the case of the second offering, way, way out. Philosophy and Kafka is a collection of essays, edited by Brendan Moran and Carlo Salzani, that view Kafka from a diverse array of philosophical viewpoints, from Socrates to French Theory, and (almost, but not quite) everything in between. My First Kafka is the quirky Hasidic writer and game designer Matthue Roth’s attempt to bring Kafka to children without giving its young readers “unsettling dreams,” for which he enlists the ornate black-and-white illustrations of Rohan Daniel Eason. One of these volumes may change the course of Kafka studies forever, and the other will lull your children to sleep. But which is which?

Roth’s child-friendly adaptation of Kafka’s best-known story, The Metamorphosis (Die Verwandlung), has a daunting task: to make a 90-page anti-novella appropriate for story time in both length and content. Gregor’s first agonizing attempt to get up, which in the original requires several pages of Kafka’s endless sentences, is abridged thusly:

Gregor tried to leave his bed.

It was harder than he thought

to move all his small legs

at once.

If he moved one,

all the others

wanted to move as well.

Those familiar with the style and tone of Kafka’s less-verbose sentences (e.g., “For we are like tree trunks in the snow,” or “Denn wir sind wie Baumstämme im Schnee”) will recognize that Roth has worked hard to make Kafka’s famous longer sentences read like his shorter ones. To the tone, Roth has granted The Metamorphosis only the tiniest bit of extra gentleness—tiny, because something Kafka readers often overlook is the rather unnerving gentle touch—or at any rate lack of pathos—of Kafka’s German, in stark contrast to the gruesomeness of the story’s content. In the original (my translation), even in the story’s most violent scene, as Herr Samsa pelts his grown son with apples, Kafka writes with a surprisingly measured tone:

A weakly thrown apple grazed Gregor’s back but skidded off harmlessly. But another one, thrown immediately thereafter, drove hard into Gregor’s back. Gregor wanted to drag himself away, as if he could make this surprising and unbelievable pain disappear with a change of location; alas, he felt instead as if he were nailed to the floor, and lay stretched out in complete confusion of all his senses.

Roth’s version removes all difficult clauses and longer words, but retains both the melancholy and the gently-narrated violence, made just slightly more gentle:

One hit his back

and fell off.

Another dove into

Gregor’s back very hard.

The apple felt like it

had been nailed there.

Granted, this is still on the darker side of children’s literature, and the stories that can be made even this child-appropriate are limited—rebranding Kafka’s famous story about a torture machine as In the “Tickle Colony,” for instance, would be a stretch—but what Roth has done, with The Metamorphosis in particular, actually accomplishes quite a literary feat: It grants a startling primacy to Gregor’s infantilization and helplessness, which are brought to life in Eason’s whimsical, intricate illustrations. Yes, Kafka famously forbade the depiction of Gregor to his publisher Kurt Wolff. But if Wolff had offered Gregor as a series of interconnected, art deco zigzags and curlicues, with an antenna mustache and his insect legs poking into whimsically askew Oxford dress shoes, laces undone, Kafka might have changed his mind.

Further, Eason’s forbidden illustrations completely dismiss the impulse to read The Metamorphosis as modern (or postmodern) metaphor, forcing children—and us—to view Gregor as literal and accept the consequences. (No one reads their children bedtime stories about “late capitalism” or the self-loathing inherent in the “becoming-animal”—or at any rate no one should.) Distilling Kafka down to his child-version—to his barest and gentlest essence—reminds us of the literary qualities that make him great, especially his macabre whimsy and his flair for the impossibly literal. These are also the qualities that make him the enduring subject of grown-up literary criticism.

Indeed, grown-up academics Brendan Moran and Carlo Salzani write that the purpose of Philosophy and Kafka is to “indicate some ways in which Kafka’s writings are a rich nexus for considering various conceptions of the relationship of literature and philosophy.” The result is more than a dozen chapters that cover a great deal of territory, from Socrates to the 20th-century political philosophers Hannah Arendt and Hans Kelsen, to a healthy representation of the French Theory that I keep hearing (and hoping) no longer dominates literary study.

Several of the readings are illuminating. Andrew Russ, for instance, argues that Kafka’s work has a haunting ability to dramatize the absurdity of a philosophical outlook by taking it literally. The post-Kantian intellectual world, in which Kafka and all other 20th-century German-speaking intellectuals were participants, was plagued with dualism, the miserable effect of barricading those things we can know through empirical experience from the noumena we cannot: “God, world, soul, unity, freedom, purpose, etc.”

Also welcome is Kevin Sweeney’s “‘You’re nobody ’til somebody loves you’: Communication and the Social Destruction of Subjectivity in Kafka’s Metamorphosis,” which addresses an issue that even non-academic Kafka readers find paramount: Is Gregor Samsa still human under there? Sweeney gives us three competing definitions of “human”: Social constructionists say our peers define our humanity; the “Lockean-Cartesian” view requires both self-awareness and successful communicative ability; the behaviorist view classifies our acts, and thus us, as “human” or “animal.” The brilliance of The Metamorphosis, Sweeney argues, is its willful ambiguity in all three of these characterizations.

Equally fascinating are the two strongest political essays in the volume: Isak Winkel Holm’s “The Calamity of the Rightless: Hannah Arendt and Franz Kafka on Monsters and Members” and Paul Alberts’ “Knowing Life Before the Law: Kafka, Kelsen, Derrida.” Holm is gripped by Arendt’s description of The Castle’s K. as a “despised pariah Jew,” and this inspires him to view Kafka’s rather unorthodox portrayal of his role as sometime manager of the Prague Asbestos Factory through Arendt’s famous description of rightlessness (a combination of contingency, inhumanity, inequality, and speechlessness). Although Kafka’s canon is viewed in some scholarship as eerily prophetic of the totalitarian horrors to come, Holm instead concentrates on Kafka’s unsettling description of dehumanizing the factory’s all-female workforce.

Whereas Arendt is a household name, Alberts introduces us to the world of the legal philosopher Hans Kelsen. Kelsen’s fascinating account of the law, which Alberts describes as “a given normative system empowered with its own logic and backed by believable threats of sanctions against contraveners,” is revelatory about Kafka. For Kelsen’s system depends upon a “Basic Norm” (Grundnorm), “a single deep underlying norm that operates as the implicit ground or foundation for all other normative legal statements.” And, further, this Basic Norm “cannot be articulated—for any articulation of a ‘deepest principle’ would itself require another deeper norm stating that it should be obeyed or considered binding.” Like the Law of The Trial, its defining characteristic is that one can never have access to it.

While Philosophy and Kafka contains many valuable insights, however, rather than offering the philosophical novelty Moran and Salzani promise, many of the contributions offer the same French Theory-influenced interpretation that has, if not dominated, at least populated literary studies since its ascent half a century ago. Any reader not currently completing a dissertation on Deleuze is likely to find much of this volume’s contents about as intelligible as Kafka’s Explorer finds the writings of the Penal Colony’s Old Commandant: “a labyrinthine criss-cross of lines.” Peter Schwenger, for example, relies on Emmanuel Levinas’ treatise on darkness (which is “filled with the nothingness of everything”) to elucidate, as it were, the relationship between Kafka’s writing and his well-documented insomnia (“I spent half the night not sleeping and the other half awake,” he once lamented). What results is about two pages of analysis of The Castle as an example of insomniac “circular thought,” another half page working with an obscure Kafka fragment called “At Night,” and eight pages volleying between Levinas, Maurice Blanchot, and other theorists whose parlance will alienate anyone outside the Theory club.

The illuminating moments of Philosophy and Kafka will reward curious fans of Kafka’s work. However, its Frenchly frustrating passages remind me why so much academic literary discourse is destined to be not wholly unlike The Trial’s Law, inaccessible to anyone not already in its official echelons. Given the choice between Moran and Salzani’s anthology and Roth’s children’s introduction, even the most bookish non-specialists will probably choose the latter.

However, it is unfair to compare Philosophy and Kafka with My First Kafka in this way, as these are works in vastly different categories. One is a philosophically original exploration of often underrepresented aspects of Kafka’s oeuvre that may have a lasting impact on the genre—and the other is a book of critical essays.

Suggested Reading

Which Religious Zionism—and Which Cliff? A Response to Hillel Halkin

The ripple effects of the recent Israeli elections and their outcome are being felt throughout Israeli society. Hillel Halkin raises many valid concerns about the consequences of the election, but…

Cynthia Ozick: Or, Immortality

Ozick is as marvelously demanding, harrumphing, and uncompromising as she has always been.

A Harem of Translators

Singer insisted that all foreign-language translations of his work be based on the English versions. And most of them were done by young women who closer to typist-editors than true translators.

Cognitive Dissonance

Gordis replies to his critics and outlines his positive vision for the future. His proposal may surprise you.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In