Second-Hand Jew: A Self-Portrait in Scenes

In the summer semester of 1982 I used to go to the English Garden in Munich rather than my seminar on Thomas Mann. I got up late, showered, and cycled to the Eisbach canal. The others would be there already. We listened to Heaven 17 on our Walkmans, we discussed Bret Easton Ellis’s first novel, and the beads of sweat on the girls’ arms dried quickly in the sun. In the afternoon I sat at my desk at home, closed the window, which I had covered with newspaper, and wrote a few pages. Three months later I’d finished: two hundred pages, my first novel. I took it to Israel with me so that my sister could read it, and when a suitcase bomb exploded twenty meters away from me at the Munich airport I shielded the manuscript with my body. My sister didn’t read it until just before I left. Then she said: “I thought Thomas Mann was dead. Anyway, if you ask me, he’s not a good example.”

One of the girls I met at the Eisbach was the daughter of Joachim Kaiser, as important a literary critic as Marcel Reich-Ranicki. Another of the girls was the daughter of George Moorse, the Jewish poet and film director from Brooklyn, who in 1971 made Lenz, a sad, wild film with a great deal of tearless silence at the end. There were also the two daughters of the gallerist Heiner Friedrich, who went to New York one day to be a Sufi dancing dervish and get rid of all his memories of Germany. And for a while Laure also came, the asymmetrically beautiful daughter of a Swiss banker with a scar from an accident on her long, sun-bronzed back. I had approached her with a bold grin in the cafeteria in Schellingstrasse where the students of German language and literature met—and to my astonishment she hadn’t run away from me.

What did Laure see in me? Probably the same as the others. The Friedrich girls thought I was cute, they said, because I was just like Woody Allen. I didn’t understand that. I was tall, lean, played football, and did not turn every conversation into dialogue for a movie comedy. And I would never have thought anyone could think me cute. I was with Kiki, George Moorse’s unloving daughter, for three short months. We usually went to her place, where she lived with her mother and brother in Römerstrasse in the Schwabing district, and the three of them were always so happy and yet also sad in my presence as if I wasn’t me at all but their Jewish American father and husband who had left Römerstrasse long ago.

After Kiki had broken up with me and I had broken up with Laure, and the Friedrich girls had moved to be with their father in New York, the only one of the girls I still saw was Henriette. We were friends, or almost, and she soon told her famous father about me. What did she say, I wonder? “Papa, I know this boy who comes from Prague, his parents come from Russia, and he says he wants to win the Nobel Prize for Literature.” Or maybe, “There’s this boy at the Eisbach with black curly hair who talks as fast as you do.” Or, “Would you like to read something by a friend of mine sometime, Papa? I don’t know his stuff, but he’s Jewish.” It will have been something like that. Why else did Henriette tell me one day that her father would like to read my novel? Like to read my novel? Joachim Kaiser? Why not read Böll or Handke? Why not a rediscovered manuscript by James Joyce?

At the beginning of the eighties, there were two kinds of Jews in Germany. Jews who didn’t live there anymore, who had fled to Palestine and America, who were in the reference books. And Jews who were still there, a few inconspicuous businessmen, doctors, and their children, who appeared briefly on TV on November 9 every year, a small, dark group of people in front of a gigantic menorah or a slate tablet hung at a dramatic height and covered with barely legible Hebrew characters. It rained, and it was windy, and then they were blown away, and they didn’t have their thirty seconds on the news again until the next November 9.

Someone like me wasn’t foreseen in Germany. If asked what I was, I said, “I’m a Jew.” I said it because it was true, and I was surprised that other people were confused. I noticed they were confused because they immediately changed the subject, smiled as if moved by emotion and said, quietly, “I see.” It didn’t bother them; some of them were even interested. And it never stood in the way of friendship between them and me, their visitor from a time that, by the wish of 33 percent of Germans, had come to an end in January 1933.

I had discovered that I was a Jew and nothing but a Jew at home, from my Russian father who, in his youth, had idolized Lenin like a god. Then Stalin’s men threw him out of the party in 1949—because he was a Jew—and to be a Jew, which he had never been before, became his religion, although a religion minus prayer shawl and synagogue. He passed some of that on to me. I am a Jew and nothing but a Jew because, like all Jews, I believe only in myself; I don’t even have a God to be angry with. I am a Jew because almost all my family before me were Jews. I am a Jew because I don’t want to be a Russian, a Czech, or a German. I am a Jew because even at the age of twenty I was telling Jewish jokes, because the chance of catching a cold frightens me more than a war, and because I think sex matters more than literature. I am a Jew because one day I noticed how much I enjoy bewildering other people by pointing out that I’m a Jew. So the Friedrich girls weren’t so very much mistaken.

I don’t know what kind of book the famous Joachim Kaiser expected me to have written when he opened my novel at the first page. But there wasn’t a single Jew in it. There was a young man who has to decide whether he wants to be a writer or not; there was a young woman so beautiful that he almost betrays his art for her sake; and there was a hysterical, hectic, artistically minded Munich that never existed in that form.

After a few weeks I heard from Henriette that her father had liked my book. I was very happy. Then I heard nothing for a long time, and then we spoke on the telephone.

“A fine book,” said Kaiser quickly, evidently concentrating.

“Thank you very much,” I said.

“Carry on like that.”

“I will.”

“But read a little less Thomas Mann.”

“I’ll remember that.”

“And keep me up to date.”

“I will.”

What? Wasn’t he going to give my book to Siegfried Unseld? Wasn’t he going to ask me to write something about the problems of artists in the Süddeutsche Zeitung? Wasn’t he going to invite me to his house to discuss Jacob and His Brothers with me?

Now the only person I could talk to about all this was Rachel, my doctor Benno’s sister. I took the manuscript to her dark little apartment in Schwindstrasse, and since we hardly knew each other, I left again at once. Rachel had black hair, black eyebrows, and she was ironic in an absolutely nonironic way. You didn’t expect to meet people like her in Germany in the early eighties. She wouldn’t accept that, and instead of assimilating or hiding, like most other Jews, she decided to publicize her origins. She opened a Jewish bookshop in Munich and later another in Berlin, and for a while it looked as if she had found what for her was the right way of being German and Jewish at the same time.

A week later Rachel said I could look in again, although she didn’t have much time. We sat on a couple of large Thonet chairs in her entrance hall and discussed my book. We also talked about the bookshop she was just opening in Fürstenstrasse, and she told me about her many sleeping partners in the business, none of whom were Jews. Each of them had given her ten thousand marks to start it up, and I thought: this is rather like the Christians of Lodz or Fürth giving Jews money to build a new synagogue. And then I thought: rather a good idea.

Why didn’t Rachel Salamander like my novel? Because there were no Jews in it? She didn’t say so, and perhaps she didn’t even think so. But if someone tells you he doesn’t know why you are telling him a story in which you yourself don’t feature, then that person’s meaning is clear. When I left, Rachel didn’t tell me to keep her up to date. She gave me back my manuscript, smiled in her ironically nonironic way, and said she had left a sheet of paper with some notes of her own in the manuscript, perhaps I’d read them. At home I just skimmed the notes quickly, because I was still feeling annoyed with her, but there was one sentence that I couldn’t ignore: “If you’re going to use paranoia, lay it on thick. Think of Kafka!” Kafka, not Thomas Mann. I was making progress.

Hermann Geduldig was an anxious, aggressive man with the face of a melancholy sailor. I was sitting in a small basement room, in his seminar on the literature of exiles, and sitting next to me was Nini with her bobbed hairstyle and the fresh, dark complexion of a young woman who would be said, in Germany, to look as if she came from the south of France. Nini and I were talking to each other nonstop while Professor Geduldig was speaking, quietly and with a stutter, about Remarque and Döblin. Once, in midsentence, he asked me to leave the room and he went pale. Even when I was listening attentively, the pupils of his eyes darted about as he checked up on me. And when I said, in my paper on Feuchtwanger, that Feuchtwanger had been the Karl May of the educated, an idealist who had known how to make a million, first in Germany and then in America, out of writing books, Professor Geduldig shouted at me, “What do you know about it? Have you any idea what it means if you have to begin your whole life over again? And you go talking about literature!”

Nini and I once spent a weekend together in my large, cold room in Solln. I had two mattresses, my desk was an old cupboard door laid over two piles of crates that had once contained mineral water, but I had a real Bechstein grand. I sometimes played to Nini on it. Or we watched TV together and kissed. Or I told her how my parents had begun their whole lives over again twice, once in Prague, once in Hamburg, and Nini told me about her odd relationship with Professor Geduldig. After that I sat down again at the piano, which had been brought from Eger to Deggendorf on a handcart fifty years ago. Its owners wanted a new one, but they were afraid of what their Sudeten German grandmother would say, so they put an advertisement in the evening paper and lent me the old piano. Now I played the jazz version of “Mein Schtetele Belz” on it.

Professor Geduldig’s mother had been the photographer Anne Dessauer, Alfred Eisenstaedt’s best pupil. His father was an art dealer, first in Flechtheim in Berlin, then in Basle, where the family had gone to escape the Nazis. When I wasn’t a student anymore, I happened to find a book by Anne Dessauer in the Amalien bookshop and bought it for five marks. She had photographed them all: Feininger, Umbo, Xanti Schawinsky, herself half-naked, Max Beckmann laughing. In her photographs the world was black and white, fast and Jewish—as Jewish as Central Europe itself before the war. It was all different after the war: Central Europe wasn’t Jewish anymore, Anne Dessauer was no longer a photographer. She just photographed her children now and then, and one of the photos showed little Professor Geduldig. He was hugging his teddy bear, looking sad and bewildered—a caricature of the eternal emigrant child.

Professor Geduldig didn’t behave strangely to me because of Nini. Or yes, perhaps he did, a little. But above all he saw himself in me—and that was all wrong. I should be going through his trials, but I was lucky enough to be a young emigrant in a better time. Whatever exactly it was about me that annoyed him, at the end of the semester he gave me my certificate with bad grace, and after that he didn’t speak another word to me.

Fifteen years later, by which time I had published two books of stories, Hermann Geduldig gave a lecture in the twilight of Hall 1 of the Ludwig Maximilian University on Jewish characters in German literature since the war—and it was all the same as ever. I came with Sonja; I was talking to her the whole time, and Sonja, whose parents are Iranian, looked very much as if she came from the south of France. Professor Geduldig had large damp patches under his armpits from the start; he glanced nervously at me; he explained apologetically several times that he was only deputizing for someone else, so he had not prepared properly; and then, in midsentence, he turned to me and said, in too loud a voice, “So what do you think? Is there any Jewish character in a German novel with whom a German reader can identify? Does such a thing exist?”

“I really don’t know,” I faltered quietly. “I’ve no idea.” And now I was the confused emigrant child.

Yesterday I was at the flea market on Ankonaplatz. I’ve been living in Berlin for eight years, and for eight years I’ve been going to the flea market in Ankonaplatz almost every Sunday. I never really buy anything, now and then a vase for five euros, an old Rowohlt paperback because of its attractive cover, or for my daughter a bracelet that comes to pieces after a few days. Yesterday I almost bought some silver cutlery, but then the saleswoman said it dated from the thirties, so of course it had been used, and I said I’d think about it. I don’t really want to eat with knives and forks once used by Nazis.

I always thought I didn’t care one way or another about Nazis. When I’m sitting opposite an old man in the tram, I don’t see him as a Roland Freisler or a member of a Wehrmacht execution squad. Films about concentration camps showing mechanical diggers pushing the bodies of dead Jews bore me quickly, and I switch over to CNN or Who Wants to Be a Millionaire? And I don’t keep asking myself when the Fourth Reich will be coming along; I’m more likely to worry about some crazy politician popping up one of these days to abolish private health insurance.

It could be that I’m pretending to myself. Or that something’s different now. However, in the summer of 1982 I really didn’t bother much about the Nazis. All that interested me was that I was a Jew—and because of that, my first novel never came to anything. And yet the papers I wrote in my seminars were full of Jews. I wrote about Jewish associations in the nineteenth century and their depressing struggle to gain recognition in German society; I wrote about Moritz Heimann, the most outstanding prewar editor at the publishing house of S. Fischer, whose disappointment led him away from assimilated Judaism to Zionism; I wrote about Thomas Mann’s nervous aversion to Jews. And in one seminar, on medieval history, I even managed to rustle up a pope who was Jewish, which landed him with a lot of trouble and an antipope.

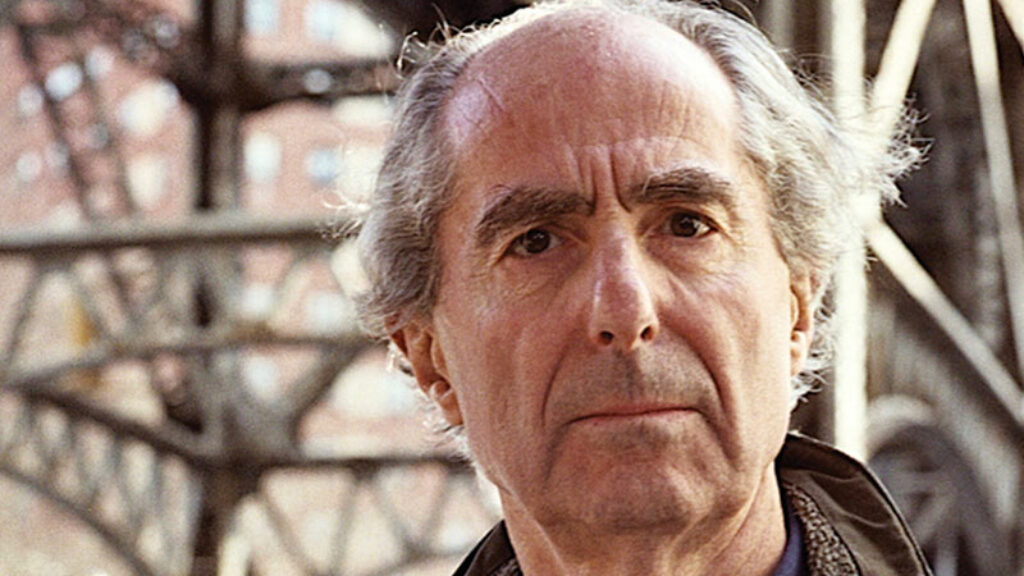

Was I being naive or egocentric? Did I really not notice that what is Jewish is always defined by its opposite, by the non-Jewish, by antisemitism, by Nazis? I didn’t—and if I did, it bored me, because after my history classes at the Kaiser Friedrich high school in Hamburg, I had heard quite enough about Nazis. But no one talked about Jews—or at least, not live ones. Then I discovered Philip Roth.

I first hear about Philip Roth in Israel. I think it was my sister’s husband, Neil, who lent me Portnoy’s Complaint. Neil came from Toronto, he’d headed an anarchist splinter group at Brandeis in the sixties, and he’d even made a two-minute television appearance on NBC. But Neil was also religious. He didn’t answer the phone on the Sabbath, he stood in a dark corner of their apartment in Herzliya and put the tefillin on, he swore when I mixed up the crockery for milk dishes and the set for meat dishes. For Neil, the Torah was the first book of the Enlightenment, and Spinoza, Marx, and Kropotkin came only after it—and before them Philip Roth’s dirty jokes, which made him laugh so loud and freely that it might have been a kind of primal-scream therapy.

Now I was lying on Herzliya beach, reading Portnoy’s Complaint and laughing. I couldn’t believe it. There really were other people in the world who were just as edgy, witty, and tyrannical as my own family, and books were written about them. Now and then I let the book slide down to my belly because I was so worked up, and I closed my eyes. I listened to the people around me speaking Hebrew; there was a radio playing somewhere, Arik Einstein singing “Ruach, Ruach,” and the sound of the matkot players striking the ball with their racquets was like a never-ending salvo of shots. Now I understood what Rachel and my sister meant when—each in her own way—they said that my novel was only words, not reality. I thought of the explosion in Munich minutes before my flight took off for Israel, and suddenly I couldn’t help laughing as much as Neil did when he told me about Alex Portnoy’s attempts to bring himself off with his sister’s bra. Five people had been severely injured, and if we hadn’t been delayed, then the bomb hidden in the suitcase would have exploded in the plane, and Mediterranean fish would now be nibbling my bones. Just after the detonation, when everyone was running about the departures lounge screaming, I had felt mortal fear for the first and only time in my life. But when I arrived at Ben Gurion Airport half a day late, my sister hardly listened to my story and told me about her own troubles instead. Outside the building where she lived in Herzliya, an old Peugeot had burned out that morning because of a hole in the fuel tank, and she had been sitting in her living room ready to wet her panties. A scene that could have been straight out of Philip Roth. Why didn’t I write about something like that?a

After Philip Roth came the other books on the shelves in Neil and my sister’s apartment, the ever-melancholy Bernard Malamud; Saul Bellow, far too intellectual for a writer; Joseph Heller, who was even funnier and more forthright than Roth and who almost came to eat borscht with my parents and me a few years later; the gloomy Henry Roth; Meyer Liben, now forgotten; Norman Mailer, not particularly Jewish at all; and Mordecai Richler with his addictive novels, always about a little boy from Jewish St. Urbain’s Street in Montreal who almost gets to be a great Canadian writer, until an antisemite reminds him who he really is—or until he tries to seduce a nursemaid.

From all of them I learned to be myself. Of course it was easier for them to be themselves, because Jews in America were Jews without a Holocaust. They didn’t have to grow up with fathers and mothers whose bad dreams took them back to the camps every night. And the non-Jews they met might or might not be antisemites, but none of them had to be ashamed because of Auschwitz or felt angry that the place had been closed down before its work was done. All of that made American non-Jews pleasantly unneurotic; they were not dangerous. For American Jews, being Jewish was simply interesting, exciting, and a cause of nervous stress. They didn’t have to show consideration for anyone in their writing or their lives, not their enemies and not their friends. If pain and hatred are not an existential factor, I thought, the whole business of fouling your own nest doesn’t loom so dramatically either.

When Philip Roth’s first book appeared in America in 1959, people told him he described Jews so well that their enemies might like his stories. Philip Roth just shrugged his shoulders and was happy to accept the National Book Award for Goodbye, Columbus. When Goodbye, Columbus appeared in German in 1982, Philip Roth wrote a short preface for German readers. He was sure, he wrote, that there were no Nazis in Germany anymore. And if there were it was all the same to him; he didn’t feel like letting them influence his imagination and his intentions. Exactly, I thought, it’s the same with me. That was my first mistake.

Suggested Reading

Harold Bloom: Anti-Inkling?

It’s a bit surprising to come across Harold Bloom’s confession that the literary work that has been his greatest obsession is not, say, Hamlet or Henry IV, but a relatively little-known 1920 fantasy novel.

Not a Nice Boy

To every author who seemed too cautious—which was nearly every author he knew—Roth gave the same advice. “You are not a nice boy,” he told the British playwright David Hare. His friend Benjamin Taylor’s memoir is . . . nice.

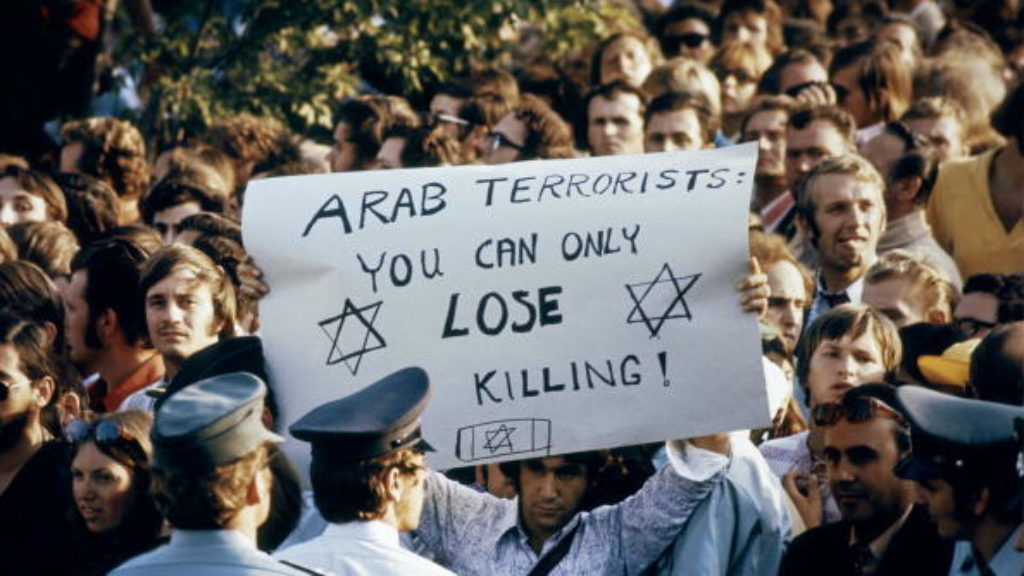

Black September

Organizers of the 1972 Olympic games were determined to avoid recalling Munich's Nazi past—which inadvertently facilitated the bloody massacre of Israeli athletes.

Something Off

There was a sense of oddness about Bruno Shulz that German-Jewish writer Maxim Biller exploits in his new novella, Inside the Head of Bruno Schulz.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In