Tragedy and Comedy in Black and White

Lately it seems to be the season of haredim on screen. My immersion in this very particular oeuvre began with Shtisel, the 2013 runaway hit Israeli TV series, which depicts a haredi family in Jerusalem in all of its complicated, charming dysfunction. (The first two seasons are now available with English subtitles on Netflix.) More recently, Autonomies (2018) presents a dystopian division of Israel into separate secular and religious states. In the United States, two recent documentaries showcase radically divergent ways of understanding the New York Hasidic community and the experience of marginal figures within it. Haredi Jews are not always interchangeable with Hasidic ones, and Israeli soap operas are different than American art-house documentaries. Yet in considering all of these offerings, certain patterns inevitably emerge. Counterintuitively, the more serious offerings in this genre are the ones with a lighter touch.

The 2017 U.S. documentary One of Us follows the paths of three young Hasidic individuals who left the insular community in which they were raised. With brooding music and a disturbing storyline, the filmmakers paint a picture of a repressive, backward society nestled within multi-cultural Brooklyn. One plot line concerns a young mother who tragically loses custody of her seven children after she leaves her community. In another, Luzer Twersky, a struggling actor with a kind of retro-Borscht-Belt manner (“It affects my image, not that I have an image, but if I did it would affect it”) calls his mother to tell her that he is no longer religious. Her answer is “ok,” but then they do not speak for seven years. The stories are devastating, but we are never told of the existence of ex-Hasidim who have warmer relationships with their families. Luzer, for one, seems to have reconnected with his family since the documentary aired.

The film opens with some unsubtle narrative: “To separate themselves from others, [Hasidim] dress like their ancestors and speak mostly Yiddish.” As Shayna Weiss argues in a review on In geveb, language doesn’t really work that way. Hasidic Jews speak Yiddish because they are part of a dynamic culture that has evolved over centuries and continues to change. The filmmakers themselves seem to have neither the interest nor the tools to paint a more layered portrait of this community.

A refreshing contrast is offered in Paula Eiselt’s 2018 documentary 93Queen. The film depicts the trials of an all-female ambulance corps in haredi Brooklyn, focusing on their dynamic leader Ruchie Freier. With a lively and evocative soundtrack, itself the product of a Hasidic alt-rocker Perl Wolfe, 93Queen deals with a less conservative subset of the haredi community than does One of Us and a considerably less fraught situation. Still, there are no simple answers.

The women of 93Queen embrace their roles as mothers and homemakers yet crave the opportunity to serve the public. Freier comes off as an ambitious mover and shaker who is motivated less by the duties of a medical volunteer than she is by the prospect of pulling off a spectacular professional coup (she recently became a New York City criminal court judge). Unlike One of Us, 93Queen is able to explore these subtleties because it does not paint the community as a monolith—rather, it is a real landscape upon which human life, in all of its variety, can play out. To get more lit-critical, One of Us plays as tragedy while 93Queen is a comedy; plenty may be askew, but people live within imperfect reality. Tragedy moves us, but comedy is a lot more like real life for most people.

Israeli cinematic treatment of Hasidic culture is often in the comic spirit, both as a genre and in terms of actual laughs. Shtisel, for example, is hysterical. Who can forget the joy of the grandmother when she gets a television installed in her room in a Hasidic nursing home: “Master of the Universe, today there is everything!”? The new series Autonomies follows a more tragic line. In the future, haredi political power results in a theocratic police state that is perpetually at odds with, but also a shallow reflection of, its secular, free Jewish counterpart. The extremist Rebbe and political leader receives secret shipments of Thucydides, which presumably influences his warmongering. Meanwhile the sympathetic haredi protagonist abandons his family to have an affair with a jazz musician on the secular side of the sociopolitical divide. This projection of a dystopian zero-sum conflict between those who are “in” and those who are “out” turns both sides into shallow simulacra of each other.

On my last flight from Tel Aviv to New York an Israeli haredi man arrived at the narrow seat next to me and my baby seated on my lap. For a moment I wondered if he would call a stewardess over and demand to change seats in order to avoid sitting next to a woman. Instead, he sat down, asked permission to tickle my baby, and watched the in-flight television screen for the bulk of the trip. While our meals were being served—mine the regular El Al kosher fare, his the more heavily wrapped mehadrin version—I asked him what he thought of the new crop of Israeli haredi TV shows. He said Shtisel got it almost right, but Autonomies was a miss. “It’s just off,” he said. Perhaps by way of explanation, he continued, “You know I am haredi on the outside but not on the inside, do you know what I mean?” I think I know what he meant, and it’s not the sort of anguished bifurcated double-consciousness some would like to imagine.

Shtisel is apparently undergoing a renovation for American audiences. Appearing under the name Emmis, the Yiddish-inflected Hebrew word for truth, the new show will take place in Brooklyn rather than Jerusalem, under the direction of the comedy writer Etan Cohen. I’m curious to see how Cohen will present haredi society to a non-Jewish American audience—and how it will be received. I understand the temptation of over-dramatizing ultra-Orthodox culture. It is rather dramatic: the stark black and white costumes, the religious rituals, the gender roles. And, of course, as time goes on the contrast with the surrounding American culture becomes ever more pronounced. Yet, as 93Queen and Shtisel remind us, language and culture are mediums through which the interesting and varied stories of life play out. Audiences are moved most deeply by those stories, not merely the forbidding shadow of their black and white backdrop.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

Remembering Walter Laqueur

Like the man himself, the pieces Laqueur wrote for JRB contain enormous insight and breadth.

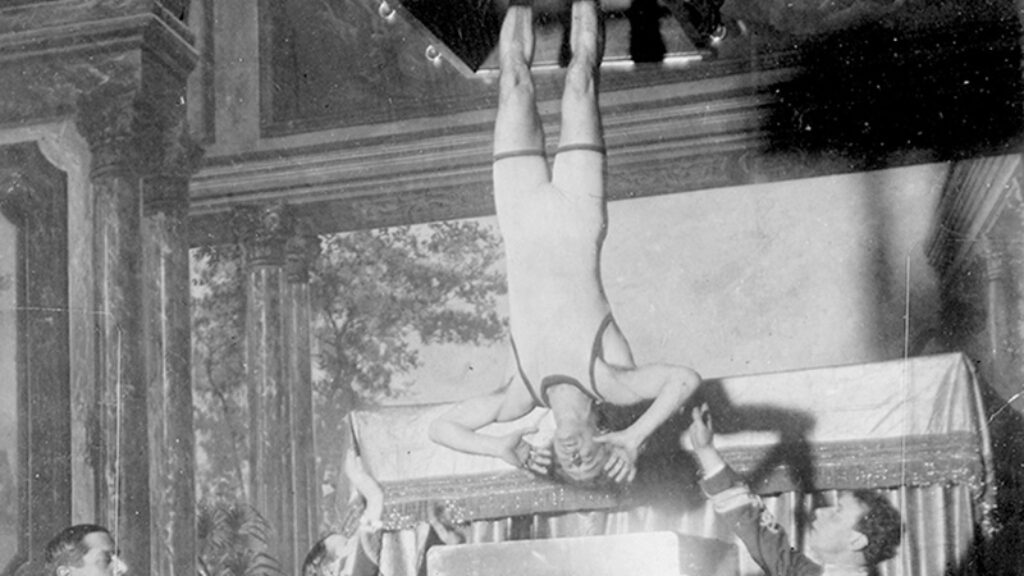

An Entrepreneurial American

“Houdini created his illusions and handed them down to his brother Hardeen, Hardeen sold them to the Amazing Dunninger, and Dunninger sold them to—my father,” writes Jerry Muller in his review of Adam Begley’s new biography of the great Jewish escape artist.

To Whom It May Concern: Mordecai Kaplan the Diarist

The father of Reconstructionist Judaism left behind a towering legacy, and seventy-seven years of personal Journals—a tightly scrawled window into his mind.

Hasidism, Jung, and the Jewish Spiritual Crisis

Carl Jung said that the great “the Hasidic Rabbi whom they called the Great Maggid” anticipated his entire psychology. He learned that from his Jewish student Erich Neumann, whose Roots of Jewish Consciousness was never published until now.

asmith

test

maurice yacowar

Thanks for that interesting intro to that scene. I was so impressed at Shtisel that I wrote an episode-by-episode analysis, Reading Shtisel (available lulu.com, amazon), along the lines of my similar study of The Sopranos 20 years ago. It's in the Jewish tradition of closely reading a text for meaning and guidance.

But I had a disturbing experience on two Shtisel chat sites on Facebook. For presuming to analyze the drama I was expelled. On Shtisel: Let’s Talk About It, the two administrators complained my pieces were too long, too many and they prevented others from reaching their own conclusions. So I was formally given a cherem: I was excommunicated for violating the principles of the community. When I insisted on analyzing the fiction the way fiction is intended to be analyzed, I was officially banished.

So I joined Shtisel Addicts. Again, my readers’ feedback was usually appreciative. But not the administrator: “Sometimes I have no idea what you’re talking about.” Then “How many times a day do you say ‘patriarch’?”

“I’ve stopped using it in my marriage," I replied. "But it comes up when I’m discussing Shtisel.” The central figure is a lying, selfish patriarch who has ruined his children’s lives. I contend that his abuse of his authority focuses the drama on abuse in suppressive systems.

But this site administrator also assumes he's the usual loving father and devoted husband. Ignoring the mass of contrary evidence reduces this fascinating failure to cliche Nice Dad. As I cited my evidence, the admin pounced: “I know where you’re going with this. Stop it.” Later: “What did Shulem ever do to you? Get off him.”

Finally: “You have an agenda.” Of course, I replied, it’s to celebrate with thought a brilliant TV drama, to try to understand as well as to enjoy it. She expelled me too.

Basically, the site admins aren't reading the story as story but as real people, to be forgiven not interpreted. They ignore the details we're given and speculate wildly over what the writers omitted.

My banishment for intellectual content is worrying. Are we not supposed to think analytically about what we’re told? If not in literature, then how will we manage in public debate, in politics, where the stakes are higher? Will our protective bubbles only admit confirmation of our prejudices? Of our misinformation? Do we really believe that an unsupported opinion is as good as a supported one? Apparently America's cultural/political split extends down to Facebook discussions of a brilliant Israel TV drama. That's tragic.