The Play’s the Thing: A Revolutionary New Haggadah

I teach at Bard, a small liberal arts college that is proud of its old-fashioned classroom culture. While I scratch out phrases on the blackboard, my laptop-free students sit among piles of dog-eared books, write with pen on paper, and share their reading and writing with the rest of the class. In our rapid transition to online courses, we have not managed to reproduce these classroom dynamics, which, along with the performance art of campus life, have suddenly gone into a bewildering springtime quarantine. As it turns out, intellectual discourse is not just a pristine mixing of minds. Thinking with others requires proximate people and things—the very components that allow COVID-19 to propagate.

Unfortunately, the same is true of the Passover Seder, which is Judaism’s liberal arts classroom. This is not just an academic point about the extent to which the Seder was or was not modeled on Greco-Roman symposia. It’s also evident in the messy mise en scène of our contemporary Seders. Here, too, participants crowd around a table, argue, declaim, spill drinks, and learn loquaciously. The matza, the bitter herbs, and the Seder plate prompt the leader, focus the bored, and engage everyone’s senses.

One may have thought that [one can fulfill the obligation of telling the Exodus story] from the first of the Month [of Nissan]…Therefore the Torah teaches “on account of this,” . . . when the matzah and bitter herbs are placed before you [so you can point at them].”

But the most important prop at the Seder, of course, is the Passover haggadah itself. More than a device to convey the content of the Exodus narrative, it is a cherished object for families and collectors. Even with such devotion, the embedded presence of the haggadah as a dynamic artifact in Jewish life is often ignored. The publication history of the haggadah has been written and rewritten, yet the story of its uses, abuses, wine spills, and matzah crumbs, remains mostly untold.

Passover haggadot have taken on a great parade of forms: ultra-Orthodox, Modern Orthodox, Conservative, and Reform; nondenominational, postdenominational, and, of course, predenominational; secular, socialist, and antisocialist; mass-produced versions printed on cheap paper and luxurious specimens lovingly copied onto vellum; Holocaust-era haggadot defiantly scribbled out in the camps and DIY hippy haggadot pasted together on the commune. Many of the most historically and aesthetically significant haggadot can now be beheld in liquid crystal display with a few clicks. The National Library of Israel, for instance, has this impressive virtual exhibition, and more than a thousand fragments of the hand-written haggadot that accumulated over the centuries in the dusty annex of a Cairo synagogue dwell currently in the purer ether of the Friedberg Genizah Project.

And yet, as I type these words from the confines of a walk-in-closet-converted-study during the COVID-19 crisis, I find the digital plenum available from my ergonomic chair both comforting, and discomfiting. If any Jewish book resists entombment behind a barrier, whether of museum glass or digital password, it is the haggadah, a text that is only fully manifest when it is a stage property on our tables.

Among the dozens of haggadot published this year, Unbound: The Recreated Haggadah speaks most to our present need for a truly social haggadah, even if this year we must restrict our socializing to immediate family.

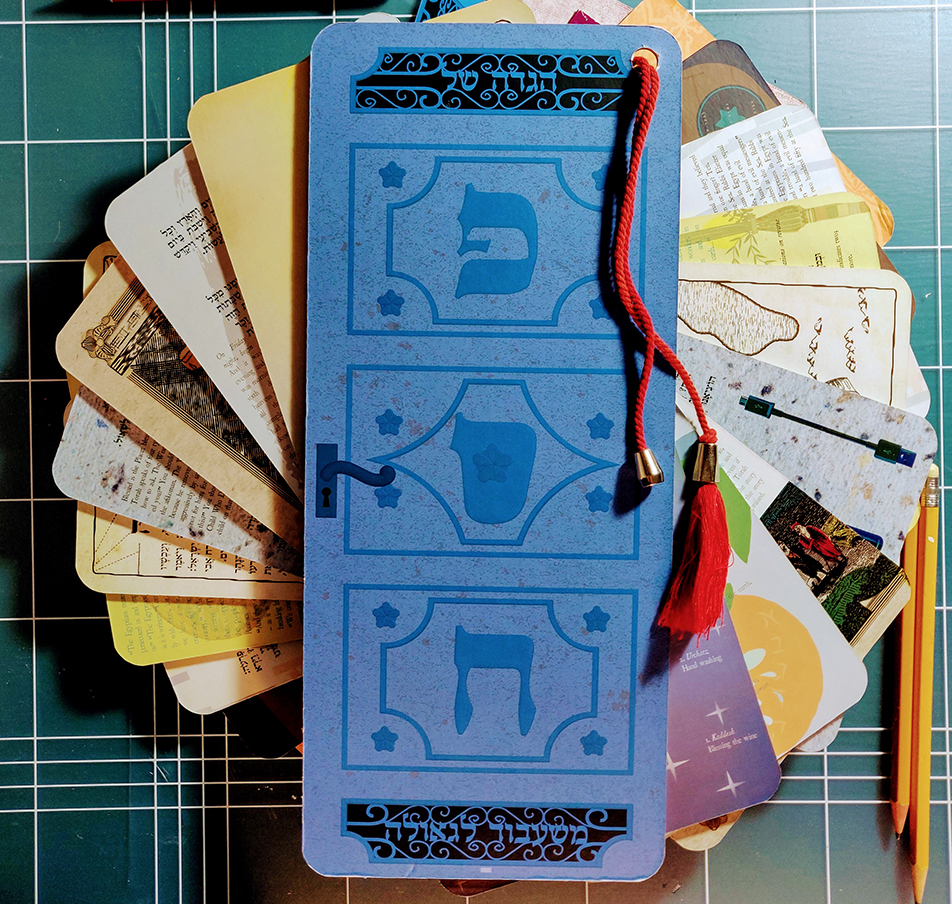

Like many great haggadot, from the Washington Haggadah (a 15th-century illuminated masterpiece named for its current home at the Library of Congress) to David Moss’s elegant haggadah, Unbound is a work of art. Its creator, Eli Kaplan-Wildmann, is a young NYU-trained theater director and designer based in Jerusalem, and his Unbound is thoughtful about its place in the history of this great Jewish book. Kaplan-Wildmann openly positions his haggadah as a performative, rather than a protected, artifact, the most important prop in the play. Apart from a thick, blood-red tassel looped through the top-right corner of its 12 cardboard planks, Unbound is literally not bound, not a book. Consequently, it invites users to engage with the text in unconventional ways, perhaps handing out individual parts to fellow Seder participants for recitation, playfully using them to construct commemorative pyramids, or, even more blasphemously, serving as big coasters for the four cups (each double-sided “page” is 5.5 inches by 13 inches, and thicker than a piece of Streit’s matza).

Unbound’s brick-like cardboard planks, saturated with color and images, have a decidedly low-tech, almost toy-like feel. While the text contains only Hebrew and English translation and lacks conventional commentary, it does not lack for ideas, which it expresses in a contemporary visual idiom while being critical of our modern technologically driven lives. The depiction of the 10 plagues takes the form of iPhone icons, so that darkness is a dead smartphone battery, and the cattle plague button has a picture of a meat delivery truck with the smokestacks of what must be a processing plant behind it. Most daringly, the death of the firstborn is drawn as the virtual demise of a person being deleted from one’s phone contacts.

For the four sons section, whose four-fold template of “wise,” “wicked,” “simple,” and “unable to ask” has served as a canvas for illustrating societal values down the ages, Unbound includes an image of a finger pointing to a line of Talmud, another finger swiping down on a smartphone, a hand holding a paintbrush, and another propping up a rifle. The novelty is that Kaplan-Wildmann has cleverly placed these prints on a rotating wheel, allowing the reader to make her own value decisions. Is the talmudist the wise child, the screen addict the simpleton, and the rifleman a wicked school shooter, or could the scheme be reimagined to celebrate a sensible Israeli soldier, critique the simpleminded Israeli haredi insistence of only pursuing Talmud study, and lament how our wired age has made us all into “the child who does not know how to ask”?

Indeed, Unbound’s visual language throughout is suggestive rather than didactic. The first page of the haggadah, devoted to the traditional search for unleavened bread, is darkly shaded in hues of black and deep purple, save for a beautifully rendered luminescent flame placed in the center of the frame. Perhaps the fire corresponds to the eternal flicker of the soul and points to the Hasidic reading of the Passover-eve chametz hunt as a ritual of self-examination. Or perhaps not.

On other pages, Unbound visually quotes some of the odd imagery of historic haggadot, including a subtle reference to the hares who have curiously sprinted across the pages of some Ashkenazi haggadot. Although there is a collage-like feel to Kaplan-Wildmann’s art, which often turns on surprising juxtapositions of style and content, his sensibility gives it a unified feel. While some of the drawings are, to my mind, less compelling, they always invite discussion. These are images that can be handed across the table or dealt like playing cards. Unbound is a truly social haggadah, using its unbound pages to embrace people in conversation, even during this “time to refrain from embracing.”

Suggested Reading

Redemption in Catalonia and Bosnia: The Sarajevo Haggadah

What does the most celebrated haggadah in the world tell us about exile and redemption?

Ink and Blood

Arthur Szyk may well be the only great Jewish artist whose work countless people recognize simply because they have attended a Passover Seder. Less well known are the explicit connections between the Egyptian pharaoh and Hitler that Szyk had embedded in his original version of the haggadah he created in the 1930s.

Pour Out Your Fury

When the Bavarian government confiscated thousands of books from monasteries in 1803, among them was an utterly unique haggadah.

Passover on the Potomac

As the holiday of freedom approaches, we explore two haggadahs—one old and one new—from our nation's capital, and think about the "audacious hope" of redemption.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In