Israel’s Northern Border and the Chaos in Syria: A Symposium

In the four-plus years since the Arab Spring, a great deal has changed, to say the least. Regimes have fallen, alliances have shifted and re-shifted, and new (and terrifying) actors have appeared on the scene. The diplomatic and strategic assumptions of several decades seem to have been upended. Nowhere is this more dramatically apparent than across Israel’s northern border. For much of Israel’s history, Syria was the country’s most formidable foe, but now it is in the midst of a seemingly interminable and shockingly brutal civil war. Indeed, one wonders whether there will be a country called Syria when it all ends, or if it will all end. For the past four years, Israel has managed to avoid getting sucked into the Syrian crisis, but how long will this be possible with Assad’s forces, Hezbollah, Iranian Revolutionary Guards, ISIS, and the al-Qaeda-affiliated al-Nusra Front on the border? And how does the terrible and extraordinary flow of refugees affect the strategic equation in this chaotic new Middle East?

Should Israel rethink its current defensive policy and do what it can to topple the evil but increasingly shaky Assad regime? Should it seize the opportunity to deal a fatal blow to what is now the weakest link in the “axis of resistance” of Iran, Syria, and Hezbollah? Or should it refrain from action, lest it inadvertently strengthen the hand of the regime’s enemies, who might prove even more dangerous to Israel than the Assads?

We asked these questions of three distinguished analysts who have been thinking about the Israeli-Syrian relationship for a long time and who have all also been active, in different ways, in shaping it. Elliott Abrams is a senior fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations and served, most recently, as deputy assistant to the president and deputy national security advisor in the administration of President George W. Bush. He is the author of Tested by Zion: The Bush Administration and the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict. Itamar Rabinovich was Israel’s ambassador to the United States in the 1990s as well as chief negotiator with Syria between 1993 and 1996. He has written six books, including The View from Damascus: State, Political Community and Foreign Relations in Modern and Contemporary Syria. Major General (res.) Amos Yadlin has had an extraordinary career in the IDF (he was one of the pilots selected to bomb Iraq’s Osirak nuclear reactor in 1981) and served as the head of the Israeli Military Intelligence Directorate. He is currently the director of the Institute for National Security Studies at Tel Aviv University.

—The Editors

The View from the Northern Border

BY ELLIOTT ABRAMS

In early May I stood on Israel’s northern border, chatting with two extremely relaxed observers (one Canadian soldier and one Finn) from UNTSO, the UN’s Truce Supervision Organization. For many years the UN’s Golan observer force has been a relaxing assignment, because the Assads, father and son, chose to keep the border quiet—and keep Syria frozen in unchanging tyranny.

No longer: Syria is a graveyard now, with more than 200,000 dead, and a base for jihadis. The humanitarian crisis is greater than most acknowledge: There are four million “registered” refugees, but the true number is certainly larger, and half the Syrian population has now been driven or fled from their homes. This places immense burdens on Jordan and Lebanon: How does a small country handle 1.5 million refugees? Moreover, the sheer number of refugees has demographic and therefore political implications. Lebanon was, just a few years ago, thought to have a Shi’ite majority, and Jordan a Palestinian majority. No longer—not if we are counting the people actually living there now. And given the slaughter in Syria they are not going home, because their homes are gone.

This humanitarian situation affects Israel, as wounded refugees make it across the border seeking medical help—which they receive. But the numbers are small, and the burden is not great. What is great is the risk that Israel now faces because its northern neighbor has fallen apart.

Bashar al-Assad is slaughtering Sunnis. His regime’s base is in the Alawite community, only about 12 percent of the population in that 74 percent Sunni country, so he keeps power by sheer brutality. That population imbalance should have led to his defeat already, but he is supported by Hezbollah and Iran. Hezbollah fighters and Iranian Revolutionary Guards are on the ground in Syria—a Shi’ite expeditionary force. Sunnis from around the world have reacted by enlisting in the struggle: Assad’s mass murder is the best recruiting tool ISIS has. Syria is now a battleground between Assad and his Iranian and Hezbollah backers, the various jihadi groups affiliated either with ISIS or al-Qaeda, and a third and weaker group of rebels the United States supports with an anemic, almost pathetic train-and-equip program.

Israelis are not, or not yet anyway, very afraid of what’s happening in Syria. They are more focused on Hamas in Gaza, with which they have fought several wars; on the Iranian nuclear program and the likely (and in their view dangerously inadequate) deal between the United States and Iran; on Hezbollah, Iran’s great ally and proxy, with over 100,000 missiles and rockets trained on Israel; and of course on their own internal politics, with Netanyahu having just formed a government that has only a one-vote margin in the Knesset. Military officers are almost laconic in noting that projectiles of various kinds—shells and rockets from the fighting across the border—land in Israel regularly, but appear to be by-products of the Syrian war rather than attacks on the Jewish state.

True enough—for now. And if the Islamic State’s gains in Iraq and Syria are reversed—by American bombing, Shi’ite militias backed by Iran, the Iraqi Army, the Kurdish Peshmerga, Syrian rebels, or the combination of this motley set of forces—the barbarous organization may never look south. Perhaps and, then again, perhaps not. Perhaps ISIS will survive and thrive in Iraq and Syria, and then start thinking about Al Quds. Perhaps reverses will come, but they will lead ISIS to reinforce its Syrian redoubt and seek more recruits and more fame by taking on the Jews.

That’s the new risk up north for Israel. And the old risk remains: the well-equipped and well-trained forces of Hezbollah in Lebanon. Hezbollah’s willingness to do Iran’s work in Syria, where it has lost by most estimates over 1,000 men, suggests that it would indeed start a war with Israel should the Israelis strike the Iranian nuclear sites. That would be a major conflict, dwarfing Israel’s effort nine years ago in the summer of 2006. The price for Lebanon and for Israel would be high. I did not find the Israelis quaking about this. I found them very, very Israeli: If it will come, it will come, several generals told me.

Much has been written recently about the new “objective alignment” between Israel and the Sunni states: Jordan, Egypt, and the Gulf monarchies. They all oppose Iran’s growing power, they are all fighting al-Qaeda and ISIS, and they all worry about what they see as a decline in American power and willingness to act. The risk to Israel of a conventional war with an Arab state is next to zero today. Nor are Israelis worried greatly about Palestinian terrorism. It continues, but Hamas has something to lose in Gaza and seems not to want another round, while in the West Bank the Palestinian Authority glorifies dead terrorists but opposes new violence. All that would mean a real improvement in Israel’s security situation, were it not that its northern border has moved from quiet to shaky. The forces on the other side of the Syrian border cannot be deterred the way a state, or even Hamas, can be. That they might be killed slipping into Israel is not ideal from their perspective, to be sure, but there are plenty of recruits still appearing in the form of Muslim youths from Tunis and Milwaukee and Lahore and Riyadh and London. And think of the glory in confronting the Jews!

It has not happened yet. Those UNTSO officers drank their tea and didn’t even bother to look across the border through their very large binoculars. But when you fly over northern Israel, you see plenty of preparations for the day when the Syrian slaughter gives birth to cross-border attacks. The Israelis appear as relaxed as the UN guys. But they aren’t.

The Enemy of My Enemy

BY ITAMAR RABINOVICH

Of Syria’s five neighbors, Israel has been the least involved in the turmoil that is devouring the country and the least affected by it. Turkey and Jordan have supported different factions of the Syrian opposition. Hezbollah, the Lebanese Shi’ite party militia, terrorist organization, and Iranian proxy, has conducted much of the fighting on behalf of Bashar al-Assad’s regime. ISIS, the jihadi organization, has assumed control of large swaths of land in western Iraq and eastern Syria. But Israel has engaged only in limited skirmishes along the ceasefire line in the Golan and a few pinprick attacks on weapon systems about to be delivered to Hezbollah. While Turkey, Jordan, and Lebanon have taken in millions of Syrian refugees, Israel has opened its borders to supply largely unpublicized humanitarian aid to people who remain enemy civilians.

Keeping Israel out of the fray is certainly the wish of the Assad regime and its patrons, Iran and Hezbollah, that have, on the whole, been careful not to provoke the Jewish state into taking strong action. They know full well that Israel could weaken the regime’s air force and armored units enough to expose them to defeat by the opposition. Iran’s calculus has also been affected by its own nuclear ambitions. It no doubt fears that a major clash in Syria or Lebanon could lead to an Israeli attack on its nuclear installations or at least have a detrimental effect on its negotiations with the P5+1 nations.

Israel, for its part, has looked at the Syrian crisis through two lenses. The first is focused on Syria itself. While Israel has fought several costly wars directly with Syria and has faced Syrian-supported Hezbollah forces in southern Lebanon, it has also, since 1991, conducted round after round of serious negotiations with the Assad regimes. Five Israeli prime ministers have conveyed to Hafez and Bashar al-Assad their hypothetical, conditional willingness to come down from the Golan Heights in return for a satisfactory peace and security package. Indeed, up until the eve of the civil war, Benjamin Netanyahu was party to a mediation effort conducted by the American diplomat Fred Hof. When the demonstrations against the Assad regime turned into a full-fledged rebellion in 2011, Israel had to decide what it preferred: the Syrian regime’s survival or a rebel victory.

Two schools of thought quickly crystalized: The first argued that “the devil we know” was preferable to the prospect of an Islamist takeover. The second, more optimistic school of thought envisioned the prospect of significant change for the better in Syria and Lebanon and advocated intervention on behalf of the rebels. Netanyahu’s government chose the former course. It drew redlines and strove to impede the transfer of advanced weapon systems to terrorist organizations, first and foremost Hezbollah, by carrying out several (officially unacknowledged) surgical air strikes against such deliveries. It also retaliated against every shot fired across the Syrian-Israeli ceasefire line in the Golan and initiated limited (also unacknowledged) tactical cooperation with jihadi groups along that line to prevent their shared enemy, Hezbollah, from extending its zone of confrontation with Israel.

Netanyahu’s prudence was in tune with the general conservatism his government displayed in dealing with other matters related to national security. It was also, of course, a reflection of what Israel has deduced from its failed attempt in 1982 to shape the politics of a neighboring Arab country. Of course, even the optimistic school of thought had to admit that Israel’s options were always limited in the Syrian arena. If Israel wished to support a secular, moderate opposition in Syria (when it seemed that one did exist), any signs of such assistance would have been seized upon by the regime as proof that the rebellion was not an authentic movement but rather a conspiracy hatched by the United States and Israel.

But, of course, the second lens through which Israel views the Syrian crisis is the wider one that encompasses Israel’s overall interests and place in the Middle East. Israel had an understandably difficult time sizing up the long-term significance of the Arab Spring in 2010 and 2011. Was it a wave of viable democratic reforms that would create a different, ultimately more hospitable region, or was it a fleeting moment that would produce pressures on Israel (from the Obama administration, for one) to take dangerous risks? Soon enough, however, the Arab Spring gave way to a somber winter—in Syria more than anywhere else.

Syria also became the arena for a proxy war between Iran and its regional rivals. Israel has a major stake in the outcome of this conflict. It realizes that Assad’s fall could be the prelude to a change in Lebanon and to a weakening of Hezbollah that would constitute a blow to its most threatening regional enemy: Iran. If this were to occur, it would be worth the price of an ISIS presence on Israel’s border, undesirable as that might be.

The more aggressive policy recently adopted by Saudi Arabia and the greater degree of coordination among Saudi Arabia, Turkey, and Qatar—and their proxies among the rebels—seem to be having an effect. Several victories in the field make it conceivable that the Syrian regime might be near defeat. At the same time, Hezbollah has been making a more aggressive effort to establish itself in southern Syria. If these two trends persist and intensify, they could break the deadlock in the country and confront Israel with new choices. Under such circumstances, Israel’s best bet would be to adhere to the successful policy of the past four years and watch from the sidelines as Saudi Arabia and Turkey defeat Iran in their proxy war. Whether that will be possible is another question.

Undermining Assad

BY AMOS YADLIN

Any analysis of the Syrian cataclysm must begin with a somber acknowledgement of the human tragedy that is still unfolding on the other side of our border. With over 200,000 Syrian fatalities already, including some 10,000 children, the Syrian civil war is as ghastly a conflict as any that has occurred in our time. How can the world allow such things to go on?

Much like its Western allies, however, and conscious of the limits of its power and influence, Israel has so far chosen what is basically a policy of non-intervention in Syria. It fires when fired upon, provides humanitarian assistance to those crossing the border, and prevents the introduction of advanced weapons systems from Syria into Lebanon. This policy has proven militarily effective, serving Israel’s security over the past few years.

For decades, the al-Assads’ Syria was Israel’s main military threat. With a vast inventory of chemically tipped missiles, well-trained and sizable special forces, and cutting-edge Russian air-defense systems, Syria dictated much of Israel’s force structure and posture. In pure military terms, the threat is now significantly reduced. The Syrian Army has suffered a great number of losses and defections, and, for several years now, a near total cut-off of training and new conscripts. Assad’s extensive SCUD missiles inventory has been largely depleted through attacks on his own people and cities, not Israel. Joint Russian-American action has destroyed or removed the bulk of his chemical arsenal. In fact, the Syrian armed forces are now so decrepit, that if it weren’t for Hezbollah, Iran, Iraqi Shi’ites, and Russia’s support, they would probably have already gone down in defeat. This is a major development as far as Israel is concerned, one that enables it to direct the lion’s share of its military assets and resources elsewhere. We can now focus more resources on long-range strike capabilities, missile defense, and cyber-warfare, not to speak of non-military goals that have important social and economic ramifications.

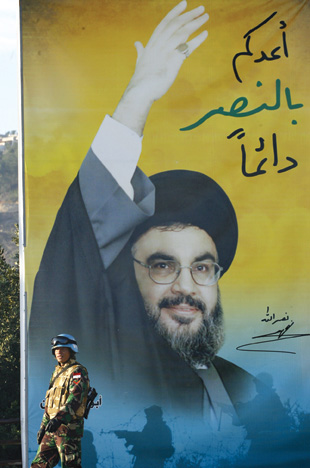

Next to the Syrian Army, Israel’s most immediate adversary is the terrorist Shi’ite militia Hezbollah. Soon after the breakdown of the civil war in Syria, Hezbollah made the strategic choice (with strong Iranian encouragement, of course) to side with Assad. That decision has had significant impact on its stature both regionally and in Lebanon. Hezbollah’s leader Hassan Nasrallah was once regarded as a heroic leader in much of the Arab world, especially after he led the 2006 conflict against Israel. He is now rightfully regarded throughout the Sunni Middle East as a senior partner in Assad’s bloody massacre of his own people.

Even within its base of support in Lebanon, Hezbollah’s decision to side so strongly with Assad has raised many criticisms, since it seemed to be at odds with its longstanding claim to be above all the “defender” of Lebanon against Israel. The unceasing flow of Sunni refugees from Syria is fueling sectarian tensions within Lebanon. Hezbollah has increasingly become Lebanon’s guardian against Sunni jihadi threats and no longer those supposedly emanating from Israel. For an Israeli observer, it is hard to assess the strategic significance of this sectarian rivalry. Perhaps Hezbollah will avoid another major conflict with Israel that could invite massive retaliation, one that would further erode its domestic position. On the other hand, it could just as well result in a Hezbollah decision to regain its raison d’être by attacking Israel.

ISIS and the al-Qaeda-affiliated al-Nusra Front now on the other side of our border are really third-order threats. Despite the alarm that these organizations have caused in the West, Israel has a long history of facing the threat of terrorism and has extensive experience in how to deal with it.

ISIS’s scare tactics, for example, are hardly likely to be effective, given the difficulty of penetrating the border. Israel’s deep familiarity with Syria and its intelligence coverage of the country, and especially the parts that are closest to Israel, make it very hard for such terrorist groups to harm Israel strategically, even if localized terrorist attacks occur. In addition, if we keep in mind the local interests of small militias, tribes, and groups in this vicinity, we can significantly reduce any incentive they might have to attack Israel or facilitate nefarious Iranian activity. Conventional wisdom aside, the Jewish state is not the primary concern of most residents of Syria, which is one reason the border has been quiet.

Perhaps paradoxically, the collapse of the Syrian state has reduced the number of threats Israel now has to face on its northern border. The four-decade-long state of “no war” on the Israeli-Syrian border may have seemed peaceful, but Israel often had to pay a high price in Lebanon whenever Syria used Hezbollah to attack it. The apparent quiet on the Golan front hid a military balance of deterrence between two heavily armed foes. Now, it is true, we experience minor provocations, including mortar fire, rifle rounds, and IEDs, but we have tools with which to counter such threats, which do not place Israel’s strategic assets in jeopardy.

Moving forward, Israel will have to choose between continuing its status quo policy, which has so far enhanced its security, and taking a more active approach in trying to weaken Assad and his regime. For many years my view has been that Assad must go, even at the cost of a takeover of the Syrian state by radical Sunni organizations. Four years ago, a takeover by more moderate forces such as the Free Syrian Army was also possible. Most importantly, Assad’s departure would deal a serious blow to the Iranian-led radical axis, which is currently Israel’s primary strategic concern. Any Sunni terror organization that could seize control of Syria would find itself responsible for a country and therefore could be deterred from taking wild actions against us. Nasrallah himself repeatedly stated that Assad’s fall would be a great victory for Israel and the United States and an existential threat for Hezbollah. Moreover, in this endeavor, Israel shares strong interests with potential allies in the Arab Gulf, which could serve to deepen regional cooperation.

Assad’s demise and the collapse of the radical axis is the best strategic outcome Israel could expect. Iran’s support of Assad with tens of billions of dollars is not accidental and represents an understanding in Tehran that its influence in Syria is strategically important.

The IDF could likely defeat Assad’s forces overnight, but doing so would risk getting us directly involved in a protracted battle. There are, however, more subtle means of accelerating Assad’s exit that Israel and America could promote, such as humanitarian corridors, no-fly zones, and targeted air assaults against Assad’s air forces. In the short-term, Israel is better off with its enemies fighting one another, rather than focusing their power against the Jewish state. In the long run, however, it would better serve Israel’s interest to team up with the United States, Turkey, and Saudi Arabia to bring Assad’s hold on Syria, and its horrific civil war, to an end.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

A Different Kind of Hero

The Nazis may have blamed Herschel Grynszpan for Kristallnacht, but he prevented them from using him in a show trial.

The Great Non-Miracle Rabbi of Prague

A new biography of Ezekiel Landau (the Noda Biyehudah) makes a controversial claim about his views on Kabbalah.

The Quality of Rachmones

Howard Jacobson's Shylock Is My Name is dead serious and very funny, high criticism and low comedy.

The Statesman

Israel's president writes a biography of that country's first prime minister.

ralph levitt

In ancient Imperial China, their prominent foreign policy approach was "let barbarians kill barbarians." This can be found in various places for thousands of years.

Obama, an abysmal President and person as well as being a silly Nobel Peace Prize winner, has nonetheless been the most effective prominent American politician on

the subject of the Syria/Iraq situation-----let the barbarians kill barbarians.

ISIS kills Hizbollah, Al-Nusra, Shia militias. Hizbollah kills ISIS, Al-Nusra and

so on, in a kaleidoscope of murder and terror between flavors of Islamic fascism.

Let barbarians kill barbarians.

andyoram

Quite reasonable analyses of the forces currently arrayed in the Middle East, reflecting a time of deadly conflict. All these commentators are comfortable making assessments and predictions with the assumption of an irreconcilable state of war among factions. When conflicts die down and enemies start to talk to each other, the same commentators find themselves lost, and might well have to give up their jobs. At the moment, compromise seems impossible, so talk of this type is safe. But various initiatives--such as the Arab peace proposal--offer the glimmer of a different kind of future, where the confident assessments being made currently would crumble.

blue1972

Not all are barbarians and some belong to very decent ethnic groups, who do the best they can. An excellent example are the Kurds, who rescued a large number of Yazidis from the clutches of ISIS.