The Quality of Rachmones

In 2012, two years after The Finkler Question won the Man Booker Prize, Howard Jacobson published a comic romp called Zoo Time. Its randy, grumpy protagonist, a Jewish novelist named Guy Ableman, complains that literary fiction is dead and that the public favors plot-driven page-turners over good writing: “Reading should be like sex,” he declares. “The ending is written in the beginning, so just lie back and enjoy the journey.” Zoo Time, sniped The Guardian’s reviewer, is a “400-page tantrum” directed at reading groups, Amazon reviews, vampire novels, Kindle, and so forth. Considering Jacobson’s Man Booker, the critic continued, “You’d think conspicuous success might have softened his attitude to the reading public.” How, in other words, dare this inflexible arriviste, newly admitted to the pantheon of English lit, act with such coarse ingratitude?

Touchy Simon Strulovitch, had he read the review, would have doubtless taken umbrage. Strulovitch is the title character’s Anglo-Jewish doppelgänger in Jacobson’s sparkling new novel of resentment and revenge, Shylock Is My Name. The book is one of a series of contemporary adaptations by top-flight novelists commissioned by the Hogarth Shakespeare project. Jacobson, in press interviews, claimed he’d asked for Hamlet but was typecast to do The Merchant of Venice, a one-liner echoing his shtick about wearying of the label “English Philip Roth” and preferring “Jewish Jane Austen.” The opening scene of his Shylock takes place in a graveyard, a location suggesting that Hamlet will haunt this book too, and it’ll be all about ambivalence as well as anti-Semitism.

“It is one of those better-to-be-dead-than-alive days you get in the north of England in February,” reads the first line, yet this is “a stage unsuited to tragedy.” We think at once of “All the world’s a stage” from As You Like It, but the more immediate allusion is to Antonio’s lines at the outset of The Merchant of Venice (which is classified as one of Shakespeare’s comedies): “I hold the world but as the world, Gratiano, / A stage, where every man must play a part, / And mine a sad one.” Shylock Is My Name is dead serious and very funny, high criticism and low comedy.

At the cemetery, two men mourn at two Jewish graves: the late mother of one, the long-deceased wife of the other, both named Leah. The first, “a man of middle age,” is Simon Strulovitch, “a rich, furious, easily hurt philanthropist with on-again off-again enthusiasms,” an art collector with “a passion for Shakespeare,” and “a daughter going off the rails.” This counterpart to Shylock’s renegade daughter Jessica is a sexually precocious teenager named Beatrice with a yen for Gentiles, currently a dopey soccer player twice her age whom Strulovitch refers to, more than once, as a “chthonic arsehole,” in an exquisite Jacobsonian meld of F.R. Leavis and Lenny Bruce.

The second gentleman, “here long before Strulovitch,” is Shylock, who is “also an infuriated and tempestuous Jew, though his fury tends more to the sardonic than the mercurial.” His Leah has been dead for more than four hundred years—she was dead even before Act I of The Merchant of Venice. This Leah is “buried deep beneath the snow,” in Manchester at the moment, since “Long ago is now and somewhere else is here.” Her husband is a wandering Jewish archetype, ubiquitous as Elijah, uxorious to a fault. He talks to her and reads to her, and she talks back and he listens: “‘Imagine that,’ Shylock says to Leah. ‘Imagine what, my love?’ ‘Shylock-envy.’ Such a lovely laugh she has.”

Yes, the ending is written in the beginning. The title Shylock Is My Name augurs that Strulovitch will become Shylock. It also reminds us, as if we needed reminding, that Jacobson, the joyful contrarian, identifies with Shylock, the silver-tongued kick-ass Jew. As described by the novel’s narrator, Shylock “is less divided in himself than Strulovitch but, perhaps for that very reason, more divisive. No two people feel the same about him.” Indeed, critics and scholars have been arguing for centuries over Shylock as villain, tragic hero, anti-Semitic stereotype. As John Gross wrote in his indispensable study Shylock: A Legend & Its Legacy, Shylock is “a familiar figure to millions who have never read The Merchant of Venice, or even seen it acted . . . There are times when one might wish it were otherwise, but he is immortal.”

As a walk-up to the book’s publication, Jacobson starred in a BBC documentary, aired in October 2015, called Shylock’s Ghost. Here the irrepressible author, who early in his career taught English literature and co-authored a critical work called Shakespeare’s Magnanimity: Four Tragic Heroes, Their Friends and Families, proves he’s done his homework. He glides past the Rialto in a gondola, visits a synagogue in the old Venice Ghetto, and chats collegially with academic experts about Shylock’s probable antecedents. Renaissance man Stephen Greenblatt cites the cruel eponymous avenger of Christopher Marlowe’s play The Jew of Malta, as well as the sad case of Roderigo Lopez, Queen Elizabeth’s converso physician, who was hanged, drawn, and quartered in 1594 for allegedly plotting to kill her. (Greenblatt speculates that Shakespeare watched the public execution.) James Shapiro, author of the definitive Shakespeare and the Jews, confirms Jacobson’s hunch that the pound of flesh has much to do with circumcision, perhaps the Pauline “circumcision of the heart” that supersedes the literal Jewish version.

Shylock is bereft of his only daughter, who has stolen the turquoise ring Leah had given him, eloped with the Christian Lorenzo, and traded the ring for a monkey. Jacobson refreshes our memory of the play: “Jessica the pattern of perfidy. Not for a wilderness of monkeys would Shylock have parted with that ring.” A monkey, as Marjorie Garber observes in Shakespeare After All, is “the emblem of licentiousness.” True, and in Zoo Time, Guy Ableman’s first novel is called Who Gives a Monkey’s?, “an elegantly profane novel” featuring a chimp named Beagle with “a blazing red penis.”

For Shylock, Jessica’s purchase of a monkey “was a profanation of her ancestors and education, everything he and Leah had taught her since she was a child.” In the cemetery, Strulovitch sees Shylock reading to Leah from an old, unidentified paperback. Later that day, he asks Shylock—by now a houseguest in his baronial art-filled manse in Mottram St. Andrew, outside Manchester—which book it was. “You should be able to guess,” Shylock replies; Strulovitch guesses the Bible. No, she prefers novels, they’ve just done Crime and Punishment and have now moved on to Portnoy’s Complaint. You’d think, given Jacobson’s ceaseless protestations, that it would be anyone other than Roth, but Shylock Is My Name is likewise fixated on the Jewish member, on circumcision as covenant, as carnal evidence of difference. And let us not forget that the Dulcinea of Alexander Portnoy’s profanation is named Mary Jane Reed, also known as The Monkey.

“Shylock,” Harold Bloom has said, “is one of those Shakespearean figures who seem to break clean away from their plays’ confines.” His language, his rage, his timelessness, burst the seams of Shakespeare’s romantic comedy and Jacobson’s satirical remodeling, too. “I will feed fat the ancient grudge I bear him,” Shylock says in Act I, with Antonio nearby. “To feed, like a cannibal, your ancient grudge,” he says in the novel, inserting a one-word clue that Shakespeare drew on anti-Semitic fantasies of Jewish barbarism and ritual murder. The hatred runs deep, both ways. The melancholy Venetian merchant Antonio, who spat on him and called him a dog, now needs the Jew’s money to help his very dear friend Bassanio court the heiress Portia, the jaded belle of Belmont, the play’s locus of fairy-tale frivolity. Shylock’s famous retort: “Should I not say, / ‘Hath a dog money? Is it possible / A cur can lend three thousand ducats?’” Shylock proposes the “merry bond”: If Antonio fails to pay by the appointed date, Shylock may claim a pound of his flesh. Was he serious? Strulovitch, four centuries later, demands an answer:

“Then let me ask you: did you hope that Antonio would fail to meet his bond so you could harm him?”

“At the very moment of the jest, maybe not.”

“Then when?”

“As the tale unfolds, so does intention.”

Pages of talk unfold, rehearsing Jacobson’s preoccupations. Shylock says:

“In the eyes of Christians and Muslims we have never been warlike enough. We are emasculated men who bleed like women. That’s what makes it so hard for them to forgive us when we do strike tellingly back. To lose to Jews is to lose to half-men.”

Strulovitch asks:

“Do you wish you’d not been stopped?”

“Stopped?” Shylock narrowed his gaze . . . “I wish, for all the good it does me, that I had not been thwarted.”

“From taking his heart?”

“From finding out whether or not I could have done it.”

A few lines later, Strulovitch persists: “Would you have done it?” Shylock launches into a monologue:

“And one more time—I don’t know. I have no more taste for blood than you do . . . My hatred for that superior, all-suffering, all-sorrowing, sanctimonious man boiled in my veins . . . I stood for order, he for chaos . . . He dealt in false obligation . . . I could not function in a universe as raw and haphazard as his . . . So yes, it’s possible—all right, more than possible—that in that fuming rage I would have found the wherewithal, the joy, the obligation—as though answering a commandment from a furious God—and as a long-owed return on those centuries of despising, as a requital of the slander, and as a perfectly ironic eventuation of all their baseless fears . . .”

He runs on and on, eventually asking Strulovitch if he has answered his question. “But Strulovitch is asleep in his chair, worn out by too much anger and frustration, too much alcohol, and not impossibly too many questions.” Speech segues to Shylock’s rumination:

This Strulovitch has a profound moral reluctance to stay awake, he thinks.

This Strulovitch asks but he doesn’t want to know the answer.

Jews are sentimental about themselves, and this Strulovitch, though he can’t decide if he’s a Jew or not, is no different. A Jew, by his understanding, is not capable of what non-Jews are capable of. A Jew does not take life . . . Good Jew—kicked. Bad Jew—kicks . . .

These famous ethics of ours have landed us in a fine mess, Shylock would like to say to his wife. If we cannot accept that we might murder as other men murder, we are not enhanced, but diminished.

This is Finkler territory, but the urgency has increased since then. In 2013, Jacobson delivered a riveting lecture in Jerusalem under the auspices of B’nai B’rith, with the title “When will Jews be forgiven the Holocaust?” It is available for Kindle devices as an essay and audio file, wherein he fumes against an insidious iteration of Holocaust denial:

The latest strategy—dear to the hearts of liberal intellectuals and to my mind the most heinous—accepts the enormity of the Holocaust without demur, but accuses Jews of not emerging from it as better people: the proof of that failure being the occupation, Gaza, the settlements, etc.

Jacobson rejects his father’s warning of “shtum’s the word” and asks “instead of Never Forget, must our motto be Never Mention?” His dystopian J: A Novel is set in a society where the past is not to be discussed and some unspecifiable catastrophe can only be referred to as “WHAT HAPPENED, IF IT HAPPENED.” (J was reviewed by Ruth R. Wisse in our Spring 2015 issue.)

In The Merchant of Venice, Shylock’s scenes—there are, astonishingly, only five of them—fasten on existential questions, expressed in heightened poetic form. “To reduce him to contemporary theatrical terms,” says Harold Bloom, “Shylock would be an Arthur Miller protagonist displaced into a Cole Porter musical, Willy Loman wandering about in Kiss Me Kate.” In the novel, Jacobson’s dilations and digressions, the inner lives of Shylock and Strulovitch, the long Socratic exchanges between them—the beating heart of the book—interrupt the often hilarious narrative, slow it down, frustrate impatient readers, perhaps even put them to sleep. The author of Zoo Time could not care less. He “doesn’t give a monkey’s . . . ,” as they say across the pond.

Jacobson re-imagines Shakespeare’s frivolous Belmont in the wealthy precincts of the Golden Triangle, where Strulovitch, heir to a car-parts fortune, lives uneasily among Gentiles. It’s a world apart from the Jewish Manchester of Jacobson’s brilliant, blistering Kalooki Nights. To house his art collection, he wants to create the Morris and Leah Strulovitch Gallery of British Jewish Art in the posh town of Knutsford. His adversary is D’Anton, a well-born importer of objets d’art. D’Anton blocks Strulovitch’s ambitions, arguing at the Cheshire Heritage planning meeting that such a gallery belonged at a “more culturally apt place, by which Strulovitch took him to mean Golders Green or the Negev.”

Strulovitch bristles at this “ancient imputation of interloperie,” but stops short of attacking D’Anton as an anti-Semite:

How, sociopathologically, it had become a foul to cry foul, Strulovitch didn’t know. But that was the state of things. No longer was it the hater who was unhinged; the real madman was the person who believed himself to be hated. Better, Strulovitch thought, when our enemies wore their loathing on their sleeves, called us misbelievers, infidels, inexecrable dogs, whipped us, kicked us, dishonoured, disempowered, dispossessed us, but at least didn’t deliver the final insult of accusing us of paranoia . . . That, anyway, with no expectation that anything would occur to change it, was the state of Strulovitch’s feeling towards D’Anton, in the period before Shylock showed up.

Populated by analogues to the Merchant, Jacobson’s convoluted plot maintains its own manic logic. The older D’Anton is fond of young Gratan, the thick-witted soccer player with an “appetite for Jewesses.” The wealthy, blithely anti-Semitic Plurabelle—“Daisy Duck mouth, golden tresses,” “a Scandinavian weather girl’s figure”—is the presenter of a fatuous cooking-and-chat show on TV. As a favor to D’Anton, she procures the rebellious Beatrice, a “performance studies” major at North Cheshire Institute, for Gratan. Meanwhile Plurabelle’s suitor Barnaby, who is another protégé of D’Anton’s (they first met at a pig roast), wishes to woo her with a painting. But, of course, the desired artwork was recently purchased by Strulovitch, who bears a grudge against D’Anton and won’t part with it.

Strulovitch is an utterly secular Jew and no Zionist—except when he reads The Guardian—but he is obsessed with Jewish continuity. “Judeolunacy,” his Jewish wife Kay would call it. One night he dragged his daughter home by her hair; Kay suffered a stroke soon thereafter. When Beatrice hooks up with Gratan, Strulovitch lays down the law: They can stay together only if—as Shylock has slyly suggested—he agrees to be circumcised. Beatrice is horrified, Strulovitch despondent. Shylock intervenes:

“Have you explained to her just what the rite of circumcision is? What it stands for? What it portends? How it’s the very rejection of barbarism? Why it’s a passage out of savagery into refinement? . . . Try sitting her down and reading to her.”

“She doesn’t go a bundle on Maimonides.”

“It doesn’t have to be Maimonides. Do you have any Roth on your shelves?”

“Joseph, Cecil, Henry, Philip? I have walls of Roth.”

“Philip will do. Do you have the one where everyone is leading someone else’s life?”

“That’s all of them.”

Here again, midway through the story, a second citation of Roth. The unnamed book is not the extravaganza of doubleness, Operation Shylock: A Confession, but rather, in the words of Jacobson’s Shylock, “the one where Roth lets the anti-circumcisionists have it with both barrels. Circumcision, he or someone like him argues, was conceived to refute the pastoral.”

Shylock is referring, it turns out, to the last section of The Counterlife, entitled “Christendom.” Zuckerman is in a London church with his English wife: “I am never more of a Jew than I am in a church when the organ begins. I may be estranged at the Wailing Wall but without being a stranger.” As the chapter progresses, mention is made of Jane Austen, Henry James, Trollope—and then, in Roth’s grand summation:

Circumcision is startling, all right, especially when performed by a garlicked old man upon the glory of a newborn body, but then maybe that’s what the Jews had in mind . . . Circumcision is everything that the pastoral is not and, to my mind, reinforces what the world is about, which isn’t strifeless unity.

“What in God’s name,” demands Strulovitch, “does refuting the pastoral mean?” Shylock retorts:

“You ask me that! You who venture into your own garden as though it’s snake-infested. Do you even own wellingtons? My friend, you are a walking refutation of the pastoral.”

Roth/Zuckerman:

Quite convincingly, circumcision gives the lie to the womb-dream of life in the beautiful state of innocent prehistory, the appealing idyll of living “naturally,” unencumbered by man-made ritual.

Jacobson/Shylock:

“You were circumcised in order that you shouldn’t, in the first days of your life, when you were still in a womb-swoon, mistake life for an idyll.”

This playful recourse to Roth may suggest that the Anglo-Jewish condition is too troubling to tackle alone. In The Finkler Question, Jacobson skewered Jewish anti-Zionists and probed the parameters of Jewish identity. Here, inspired by Roth, his Shylock anatomizes the question at its anatomical root:

“Look. The mohel’s knife acts mercifully, to save the boy from the vagaries of nature. I don’t just mean the monkeys. I mean ignorance, the absence of God, the refusal of allegiance to a people or an idea—especially the idea that life is an obligation as well as a gift. The mohel’s knife symbolises what we owe . . . We can’t be saved from nature a little bit . . . It’s all or nothing, it’s human values or the monkeys.”

Shylock Is My Name may be read as a midrash on a canonical text, a fictional meditation on anti-Semitism oddly akin to Freud’s Moses and Monotheism. After Hamlet, Merchant is the second most-performed Shakespearean play of all time. At the same time, as Harold Bloom states, “one would have to be blind, deaf and dumb not to recognize that Shakespeare’s grand, equivocal comedy The Merchant of Venice is nevertheless a profoundly anti-Semitic work.” Indeed, in the 1930s there were 50 separate productions in Nazi Germany. Would the Jewish people have been better off if the play had never been written? Not at all, insists James Shapiro: It teaches us what we are up against. The play illuminates “irrational and exclusionary attitudes” and “cultural fault lines,” which is why “censoring the play is always more dangerous than staging it.” But after the Holocaust, as John Gross grimly concludes, “the play can never seem quite the same again. It is still a masterpiece, but there is a permanent chill in the air.” It serves Jacobson well to begin his retelling in a frozen cemetery.

The prolific Hollywood screenwriter and Jewish polemicist Ben Hecht, who died in 1964, left behind an unfinished book called “Shylock, My Brother,” which speculated that Shakespeare, like the unfortunate Dr. Lopez, was a crypto-Jew. (Strulovitch puckishly “entertains a passing fancy” that Shakespeare’s ancestors, “to be on the safe side,” changed their name from Shapiro.) In a chapter entitled “Should ‘The Merchant’ Be Suppressed?” Hecht emphatically answers no:

Censorship of a classic can only belittle the censors . . . The plot of The Merchant is not the gloat of anti-Semitism, but the pain of its victim . . . The Jewish complaints against The Merchant would never, I am certain, have been made by Shylock himself were he in the audience and not on the stage.

Hecht might have been reacting to then-recent events in the New York theater world. In 1962, the New York producer Joseph Papp wanted to inaugurate his free Shakespeare in Central Park with a production of Merchant, but, as reported by Time magazine, “the New York Board of Rabbis loudly protested.” In the lofty language of a prominent Reform rabbi, the offending play was “a drama which has been demonstrated beyond peradventure of a doubt as a breeding center for those destructive forces which eventuated in the disasters of the 1930s and 1940s.” Papp, added Time, “raised an Orthodox Jew, went ahead with his performance,” which starred George C. Scott as Shylock.

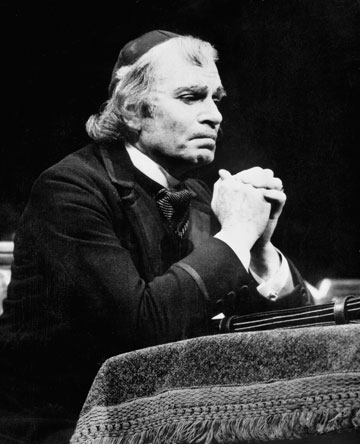

In 1974, ABC-TV aired a filmed version of the British National Theatre’s production, starring Laurence Olivier in well-tailored Victorian garb and a big black yarmulke. Prior to the broadcast, Olivier issued a statement describing the play as a “harsh portrayal of prejudice and revenge” and assured the public that he took the subject “too seriously to allow Shylock to be either sentimentalized or caricatured.” Yet as viewed today on YouTube, Olivier’s performance veers from stunning virtuosity to the brink of kitsch: Enter Jewish friend Tubal, kissing the mezuza. Shylock grieves for his daughter and the jewels she stole. When Tubal says that Antonio has lost his ships, Olivier breaks into a joyful little jig: “I’ll plague him, I’ll torture him.” Tubal reports Jessica’s trade of Leah’s turquoise ring for the monkey. Shylock cannot bear it, he weeps, opens a drawer, takes out a tallit, kisses it as he utters the hateful words: “I will have the heart of him.” Hooded in his prayer shawl, he ends the scene: “Go, Tubal, and meet me at our synagogue.” One can only gasp. Small wonder the Anti-Defamation League expressed its “grave apprehensions” to ABC.

The ADL also complained about a 1981 PBS broadcast of a BBC production: “The vicious stereotype is emphasized still further in the gratuitous use by actor Warren Mitchell of a broad, middle European accent, while the other characters speak in a cultivated English manner.’’ The director, Jack Gold, defended Mitchell’s Yiddish delivery to The New York Times: “‘We wanted to show a Jew not ashamed of being the sort of Jew he was.’’

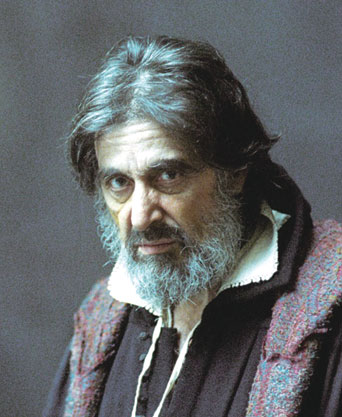

In the 2004 movie version by the British director Michael Radford, Al Pacino’s Shylock is unmistakably the wronged party, raging against an anti-Semitic society. The ADL declared this version kosher and even screened it at its winter confab for big donors held at the fabulous The Breakers Hotel in Palm Beach. The Breakers had refused Jewish guests until 1965, when it was sued by the ADL, whose meetings are now held there each year. Jacobson’s Shylock would be proud.

As the trial scene of Merchant commences in Act IV, the Duke challenges Shylock to take some money and spare Antonio’s flesh: “We all expect a gentle answer, Jew.” The ungentle Jew counters with the thrilling “gaping pig” speech:

So can I give no reason, nor I will not,

More than a lodged hate and a certain loathing

I bear Antonio, that I follow thus

A losing suit against him. Are you answered?

Portia, disguised as a man, urges Shylock to be merciful, but he refuses: “I crave the law . . . I have an oath in heaven.” Portia outwits him; he may have the flesh but not a drop of blood. Antonio is saved, and Shylock must forfeit half his wealth to Antonio and bequeath the other half to “his son Lorenzo and his daughter,” and—the ultimate humiliation—“presently become a Christian.” Portia asks: “Art thou contented, Jew? What dost thou say?” Shylock replies: “I am content.” (In Pacino’s case, he mumbles unintelligibly.) Four lines later, the Jew exits the play, deprived of closure and with an unresolved religious status.

Did he or didn’t he? Shakespeare’s ambiguity is a boon for Jacobson. Shylock sits in Strulovitch’s garden in the morning cold, making jokes with Leah about the baptism that never took place. Strulovitch: “So when you declared yourself ‘content’ to be converted you didn’t mean it?” Shylock: “‘[C]ontent’ I would never have been. Do I strike you as a contented man?”

The ending is written in the beginning, or even before. Jacobson’s dedication reads:

To the memory of Wilbur Sanders

How it is, that over many years of friendship

and teaching Shakespeare together we never

discussed The Merchant of Venice, I cannot

explain. It is a matter of deep regret to me that

we cannot discuss it now.

On completing the book, the reader wonders whether the co-authors of Shakespeare’s Magnanimity, two gentleman scholars, one of them Jewish, were so generous to one another that they dared not speak of English anti-Semitism. Shylock, for his part, has grown weary of England:

Shylock folded himself deliberately into an armchair next to Strulovitch’s. Both chairs had views of Alderley Edge on which a light snow was falling. Living here was like living in a snow globe, Shylock thought. Art or no art, he suddenly wanted to be gone. He missed the heat and the commotion of the Rialto. The brutality, too. This was no place for Jews. He had said as much to Leah. They live with their nerve-ends exposed in this country, he’d told her. You can maim with a look, in this place. You can kill with a word. Our friend Strulovitch has lost the robustness native to our people. He could be the spinster sister of a country clergyman, he is so sensitive to slights. And as a consequence of that, he cannot judge what’s worth going to war for. So he goes to war, mentally, over everything.

For Simon Strulovitch, the Jew of Venice has been a brother-in-arms, a spirit guide, a provocateur, even (as Shylock incredulously informs Leah) a “role model.”

He would miss Shylock when he went. He needed a black-hearted friend. Jews had grown so careful now. If you wrong us, shall we not revenge? No, we shall not. We shall take it on the chin and be grateful. Unless we’re in Judea and Samaria, where we’re accused of being Nazis. Coward or Nazis—which was it to be? The Rialto was not Samaria, but it too had bred a tougher Jew, Strulovitch thought. If he had, on pain of death, to be a Jew in Samaria, the Rialto or the Golden Triangle, he wouldn’t have chosen the Golden Triangle.

Act V of Shakespeare’s play reverts to idyllic Belmont, where, in the words of Harold Bloom, “the only crucial question is whether to stay up partying till dawn or go to bed and get on with it.” Jacobson’s novel winds up quite differently, juggling critical questions till the tricky end. Its 23 chapters lead to a finale called “Act Five.” Plurabelle is now preparing to throw a champagne bris on her front lawn; D’Anton is due to be snipped as a surrogate for Gratan, who is on the lam in Venice with Beatrice. Strulovitch is out for blood, and now it is Shylock, channeling Portia, who seeks to deter him with a magnificent “quality of mercy” speech: “Who shows rachmones does not diminish justice. Who shows rachmones acknowledges the just but exacting law under which we were created. And so worships God.” But Strulovitch has “deafened himself” by filling his mind with “every slight, every exclusion, every bad thing done to him and every bad thing he had done. It was more than a match, in its malignancy, for Shylock’s honeyed peroration.” Plurabelle, meanwhile, is swept away. She never dreamed Shylock “capable of such humanity,” such “Christian sentiments.” Shylock reacts with anger:

“It is wrong not to know where you got your sweet Christian sentiments from . . . Charity is a Jewish concept. So is mercy . . . How dare you think you can teach me what I already know, or set me the example long ago set you? It is a breathtaking insolence, an immemorial act of theft from which nothing but sorrow has ever flowed. There is blood in your insolence.”

“That’s what you call telling them,” says Leah. “Though I wish you’d shown a little of your rachmones to that poor girl.” “Ach, I wouldn’t worry for her,” replies Shylock. “She fucking loves me.” Shakespeare, perhaps né Shapiro, couldn’t have put it better.

It would not be cricket, as they say in Albion, to reveal how everything works out. “Victory and defeat were alike absurd,” muses Strulovitch. “On it stretched, backward and forwards, the line of risible time—all the way from the conversion of the Christians to the conversion of the Jews.” Elegant words, a civilized finish, but for Jacobson overplaying Shylock is the best revenge.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

On Old Stones, a Black Cat, and a New Zion

There is a legend that Prague’s Altneuschul was built on a foundation of stones from the ancient Temple in Jerusalem.

Thoughtlessness Revisited: A Response to Seyla Benhabib

In The New York Times, Seyla Benhabib took issue with Richard Wolin’s critique of Hannah Arendt. Wolin responds.

Stirring the Pot

A rejoinder to Jack Wertheimer, David Biale, Edieal Pinker, and Erica Brown.

Freethinker

Melanie Phillips had stumbled into the culture wars by, as she herself describes it, “the staggering tactic of actually observing what was going on.”

h_silverman

I have just finished reading the novel, and found it vintage Jacobson. His stye is polished, his humor sly, his familiarity with the sources deep. He deals so profoundly, yet humorously, with questions that engage me every day -Jewish identity, our place in the wider culture of which we're part, ever-present anti-Semitism.

There's no-one who deals with these issues better than Mr. Jacobson, who is so funny and transgressive. There's no-one whose writing I admire more.

I have read him with great pleasure for many years, always waiting impatiently for his next novel. BRAVO!

gwhepner

WEARY OF THE LABEL “ENGLISH PHILIP ROTH”

Weary of the label “English Philip Roth,”

Howard Jacobson would prefer “Jewish Jane Austen.”

“Bellowing British Behemoth,”

would link him Chicagoan who retired in Boston.

[email protected]

gwhepner

RECALLING SHYLOCK WITH BEWILDERNESS

Compared with Adam Eve was like a monkey,

declares the an aggadata in Bava Batra.

In the wilderness where I'm a poetic stutterer,

a Yekke who's anan Ostyid too, but not a Hunkie,

I recall how Shylock said he would have given

a wilderness of monkeys for his late wife's ring.

Mine's still alive, my eshet hayyil of whom I now sing,

hoping that my pounds of flesh will be forgiven,

verses that with great bewilderness I write,

which, though they don't match the sonnets of the gentile Bard,

have not caused me to be out-Portia'd and discard,

as Shylock, poor shit, was compelled, my Yiddishkeit.

I add a rhyming couplet for the sake of sonnetry,

praising her for whom my love is hardly monetary.

[email protected]