Blessing and Rebuke

Many great and humane poems have been written since, and even about, Auschwitz, Theodor Adorno’s famous dictum notwithstanding. But none written in German, or by a Holocaust survivor, has approached the greatness of Paul Celan’s strongest poems. The trauma of the war years ultimately cost Celan his life. He ended it in 1970, at age forty-nine, drowning himself in the Seine in Paris, where he had chosen “to live out to the end the destiny of the Jewish spirit in Europe.” But writing poems was almost always possible for him. Even in what Celan later referred to as “the so-called labor camps in Romania” and later, between his final bouts of madness and hospitalization, he continued to write and translate.

Now in paperback, the two volumes of Pierre Joris’s bilingual edition of Celan, which gather together for the first time in English all nine of his published volumes, testify to the possibility of translating Celan into English, although the challenge is considerable and the losses inescapable. No translation can wholly recover the uncanny resonance of Celan’s German. “Reachable, near and not lost, there remained in the midst of the losses this one thing: language,” he told a German audience in 1958 in Bremen:

It, the language, remained, not lost, yes in spite of everything. But it had to pass through its own answerlessness, pass through frightful muting, pass through the thousand darknesses of deathbringing speech. It passed through and gave back no words for that which happened; yet it passed through this happening. Passed through and could come to light again, “enriched” by all this.

Hitler’s “Thousand-Year Reich” lurks in Celan’s “thousand darknesses” and “enriched” (“angereichert,” in shudder quotes), as his biographer and translator John Felstiner noticed. Celan has “no words for that which had happened.” Instead, his words bear the mark of their passage through history in a way no language could, other than German, his mother tongue and the language of his parents’ murderers.

“Deathfugue” (“Todesfuge”), Celan’s most famous poem and his first to appear in print, is the one exception to this wordlessness. Drafted as early as 1944, shortly after he escaped or was released from the camps as the Soviet Army moved west, “Deathfugue” is the most overt poem Celan ever published. It depicts the Nazi practice of forcing Jews to perform music even as they dug their own graves, a horror that brings to mind Psalm 137: “For they that carried us away captive required of us a song.” Relentless and incantatory from start to finish, “Deathfugue” opens with the recurring lamentation of a choral “we” nurtured only by death and liberated only by incineration:

Black milk of morning we drink you evenings

we drink you at noon and mornings we drink you at night

we drink and we drink

we dig a grave in the air there one lies at ease

Other strains emerge in the fugue’s counterpoint: the shouts of a death-camp commandant and a vision of a man writing in a house—“he plays with the snakes”—and dreaming of Margarete from Goethe’s Faust (who blurs, in a plangent stroke of genius, with the beloved Shulamit of the Song of Songs):

He calls out play death more sweetly death is a master from Deutschland

he calls scrape those fiddles more darkly then as smoke you’ll rise in the air

then you’ll have a grave in the clouds there you’ll lie at ease

Black milk of dawn we drink you at nightwe drink you at noon death is a master from Deutschland

we drink you evenings and mornings we drink and drink

death is a master from Deutschland his eye is blue

he strikes you with lead bullets his aim is true

a man lives in the house your golden hair Margarete

he sets his dogs on us he gifts us a grave in the air

he plays with the snakes and dreams death is a master from Deutschland

your golden hair Margareteyour ashen hair Shulamit

The most famous phrase in all of Celan is his thrice-repeated refrain, “Tod ist ein Meister aus Deutschland”: “death is a master from Germany” or “death is a master from Deutschland,” as Joris renders it, leaving the name of the German nation untranslated. Celan would never use the word again in a poem.

No doubt many admirers of “Deathfugue” have been baffled when turning to Celan’s other poems. In the poems he began writing in the late 1950s in particular, it can sometimes seem as if all context has vanished, leaving words stranded on the page, beyond interpretation. Lamentation and elegy remain, but their explicit subject is pushed into the white space that surrounds Celan’s text, like an invisible force field. For instance:

The snowbed under us both, the snowbed.

Crystal after crystal,

meshed timedeep, we fall,

we fall and we lie and we fall.

Or:

A stillness came, a storm too came,all the seas came.

I dig, you dig, and the worm too digs,

and what sings over there says: they dig.

O one, o no one, o noone, o you:Where did it lead, as it led nowhere?

Even in translation, the reader can see some of the challenges presented by Celan’s originals. Newly minted words like “snowbed” (Schneebett) and “timedeep” (zeittief) sound more studied in English than in German, a language in which compound nouns and modifiers abound. In the final stanza above (from “There was earth inside them”), Joris takes the additional liberty of creating a compound word in English—“noone”—where Celan merely employed the common indefinite pronoun niemand, usually translated as “nobody” or “no one.” (Felstiner and Michael Hamburger, by contrast, both render the line, “O one, o none, o no one, o you.”)

Joris takes a similar approach to “Psalm,” Celan’s most well-known poem after “Deathfugue”:

NoOne kneads us again of earth and clay,

noOne conjures our dust.

Noone.

Praised be thou, NoOne.For your sake we

want to flower.

Toward

you.

A Nothingwe were, we are, we will

remain, flowering:

the Nothing-, the

NoOnesRose.

Withpistil soul-bright,

stamen heaven-desolate,

the corona red

from the scarlet-word, that we sang

above, O above

the thorn.

Orphaned and imprisoned by the Nazis, while never ceasing as a poet, Celan knew what it was to sing “above, O above / the thorn.” As Joris observes in his extensive notes, “Psalm” draws not only on the image of God forming man out of clay in Genesis but also, most crucially, on Psalm 103:15: “As for man, his days are as grass: as a flower of the field, so he flourisheth.” To the beauty and brevity of that flourishing, Celan adds an uncanny vulnerability: body and soul exposed, proffered like the reproductive organ of a flower to a godforsaken sky.

Unsurprisingly, Celan’s original is at times untranslatable. As Felstiner noted, Griffel (pistil) can also mean “stylus,” a utensil for writing—a redolent double-meaning for which neither Felstiner nor Joris have a satisfying solution. And there is the insoluble problem of entgegen, which Joris translates as “toward”: “For your sake we / want to flower. / Toward / you.” But entgegen can also mean “against” or “in spite of,” as in Felstiner’s version:

Blessèd art thou, No One.

In thy sight would

we bloom.

In thy

spite.

Celan, of course, wanted both meanings, and so both Joris’s and Felstiner’s versions are inaccurate or insufficient, as any English translation will be. Only Celan’s original is perfectly natural and perfectly poised between invocation and repudiation—blessing and rebuke—as it turns both toward and against “Niemand.”

Alhough he didn’t make their task easy, Celan would have appreciated the efforts of his translators. He began translating French, English, and Russian poems into German in his early teens, and during his nineteen months of forced labor, he made translations of Shakespeare’s sonnets and poems by Verlaine, Housman, and Éluard. He later translated Apollinaire, Baudelaire, Rimbaud, Valéry, Andrew Marvell, Lewis Carroll, Kafka (into Romanian), Dickinson, Frost, Yeats, Marianne Moore, Mandelstam, and Yevtushenko, among others. He considered his extensive translation of Mandelstam’s poems to be as important as his own work. Even “Celan” is a translation of sorts: a Frenchified anagram of “Ancel,” the

Romanian spelling of his family name, “Antschel” (it appeared for the first time in his poetic debut, a Romanian translation of “Deathfugue,” which he oversaw).

Joris suggests in his introduction that composition itself was a form of translation for Celan, from German into a hitherto nonexistent tongue: an “invented German” encompassing archaisms, dialect, specialized vocabularies, nonce words, neologisms, multilingual puns, etymological wordplay—even Hebrew. Etymologically, to translate is “to carry over,” which is often how Celan characterized his relationship to language. Language must survive a passage, must be rescued. “To save the word,” he wrote in “The Sluice,” it had to be carried “back / to and across and over the saltflood” (the word in question turns out to be yizkor).

The word’s journey from author to reader is also perilous, particularly in translation, and even in Celan’s invented German. He famously said in his Bremen speech, “A poem can be a message in a bottle, sent out in the—not always greatly hopeful—belief that somewhere and sometime it could wash up on land, on heartland perhaps.” But my favorite of Celan’s metaphors for poetry is almost the opposite of a message in a bottle. In an untitled lyric from his most beautiful collection, NoOnesRose (1963), he envisions his poem as a boomerang, tossed into the void with such craft and velocity as to promise a perfect return to the consciousness of its maker, even if no one else can catch its meaning:

A boomerang, on breathroutes,

as it wanders, the wing-

mighty, the

True. On

star-

orbits, kissed by

world-splinters, by time-

kernels scarred, by timedust, co-

orphaned . . .

displaced and discarded,

by itself the rhyme,—

thus it comes

flying, thus it comes

again and home

Suggested Reading

No Simple Return

“I stepped into the air.” Hilde Domin wrote, “and it carried me.”

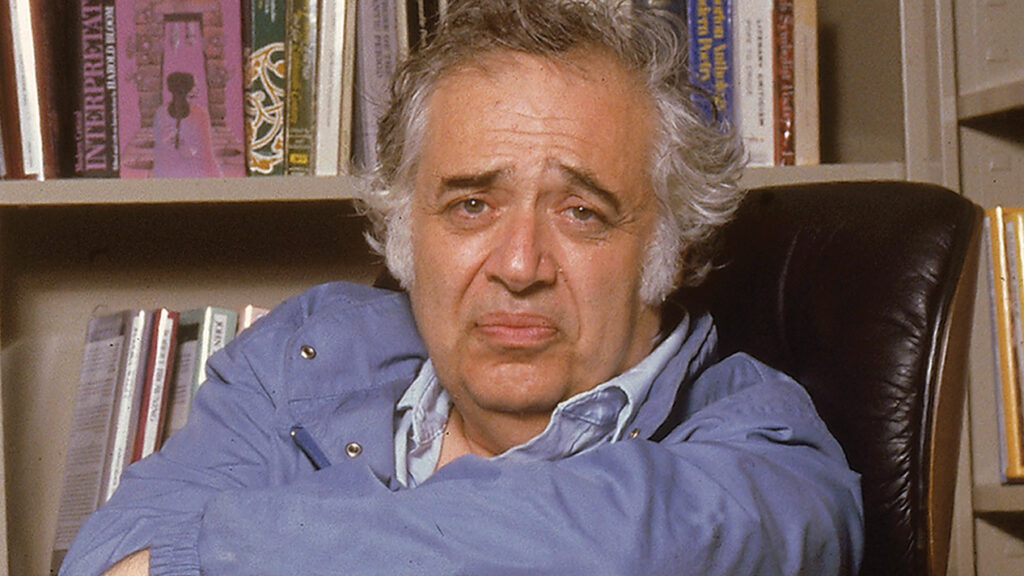

Remembering Harold Bloom

As Harold Bloom's student, I wanted to be transported to the heights of the literary sublime where he always seemed to reside, whatever the cost (it seemed considerable).

Dust-to-Dust Song

Nelly Sachs was 50 years old when she fled the Nazis with her mother in 1940. Few would have perdicted that she would receive the Nobel Prize for Literature twenty-six years later.

Funny How a Poem Can Get Under Your Skin

On Celia Dropkin’s avant-garde Yiddish break-up poem and a political insight.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In