Qutb’s Milestones

In recent years, Sayyid Qutb has become infamous as the intellectual godfather of al-Qaeda. Indeed, as John Calvert writes in Sayyid Qutb and the Origins of Radical Islam, a “consensus has emerged that the ‘road to 9/11′ traces back to him.” In their attempts to explain the movement he helped to spawn, Gilles Kepel, William Shepard, Lawrence Wright, and others have already limned the contours of Qutb’s life and thought. Calvert, however, offers the first truly comprehensive biography. Building on the work of his predecessors, he offers new insight into Qutb’s early writings as well as details of the dark days he spent in Nasser’s prisons. What emerges is a more nuanced portrait, not only of the historic Qutb, but also of the process of transformations that eventually produced Qutbism.

Qutb was born in a small Egyptian village in 1906 to a middle-income, land-owning family. He was fascinated at an early age by his country’s newly emerging group of liberal, middle-class effendis, several of whom taught at his school. “Everything about them—their outlook, appearance, and life experiences—seemed connected to an exciting new world of change, movement, and intellectual liberation,” Calvert writes. Aspiring to join them, the teenaged Qutb left home for Cairo to study at a secular teachers college. Upon graduation he found employment in the Ministry of Education and embarked on a literary career. His early writings included novels, essays, poems, and various autobiographical pieces. He would later dismiss these as unimportant, apart from having helped him to develop an elegant prose style, and it is doubtful that they had much influence on his later works. Nevertheless, they were well received in Egyptian liberal-modernist circles, and brought him into contact with leading intellectuals such as Taha Hussein and eventual Nobel laureate Najib Mahfuz.

Although he remained deeply religious, Qutb was still a liberal nationalist at this point in his life. However, in the late 1930s and 1940s, as Egyptian political movements became more ardently opposed to Western imperialism, Qutb’s views began to evolve. His writings from these years reveal frustration, even disgust, with Western civilization, which he denounced for seeking “to destroy all that humanity has produced in the way of spiritual values, human creeds, and noble traditions.” Like other Egyptian intellectuals of his generation, he began to look for more “authentic” sources of inspiration. The transformation was gradual, but by the late 1940s this meant Islam and Islamism, albeit of a reformist rather than revolutionary nature. Nonetheless, Qutb continued to express nationalist sentiments and remained committed to working within the existing nation-state system. In fact, as Calvert suggests, Qutb probably would have “accepted an Islamized version of the existing monarchical-parliamentary system . . .”

Qutb’s Islamist views seem to have taken a more radical turn durng his year as a student in the United States in 1949, which left him railing against the entire country as a sea of primitive depravity. Calvert, however, puts less emphasis on this visit than have previous authors, who often cite his horrified descriptions of the hedonism and superficiality of postwar America, especially his shock at the institution of church dances. He is inclined to suggest that the trip did more to solidify Qutb’s preconceived notions about America than it did to shape them.

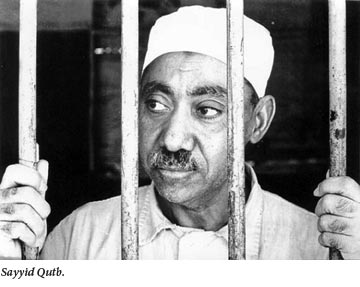

Qutb’s writings made him a favorite of the Muslim Brotherhood, and a trusted intermediary between them and Gamal Abdel Nasser and the officers who overthrew the monarchy in 1952. A few nights before the coup, these officers visited Qutb’s home, where they met with a contingent of high-ranking Muslim Brothers. The alliance did not last. Shortly after the coup, it broke up over disagreements concerning the role of Islam in the state. In 1954, Nasser had all the leading Brothers, including Qutb, arrested and put on trial. Qutb was sentenced to fifteen years of hard labor. Along with other Muslim Brothers, he was also brutally tortured.

Languishing in the Egyptian prison where he had been deposited by the regime he helped bring to power, Qutb considered what had gone wrong. Until this point, Qutb’s Islamism had been colored by Egyptian nationalism and firmly rooted in third world anti-imperialism. But now, incarcerated and abused by a nationalist and militantly anti-imperialist regime, he began to develop the uncompromising ideology that would eventually be called Qutbism. As Calvert skillfully shows, it was based on the premise that the only legitimate form of Islamic government is one in which sovereignty (hakimiyya) belongs solely to God. He decried all nationalisms as un-Islamic and unnatural divisions of the one true community of Muslims. Consequently, there was not a single Islamic state in the entire world. Every existing society was, therefore, in a state of barbaric ignorance (jahiliyya). Qutb’s solution, outlined in books he wrote and published while still in prison such as the revolutionary manifesto, Milestones, and his Qur’anic commentary, In the Shade of the Qur’an, was the formation of a revolutionary vanguard who would work to overthrow the existing barbarism and reestablish true Islam.

Languishing in the Egyptian prison where he had been deposited by the regime he helped bring to power, Qutb considered what had gone wrong. Until this point, Qutb’s Islamism had been colored by Egyptian nationalism and firmly rooted in third world anti-imperialism. But now, incarcerated and abused by a nationalist and militantly anti-imperialist regime, he began to develop the uncompromising ideology that would eventually be called Qutbism. As Calvert skillfully shows, it was based on the premise that the only legitimate form of Islamic government is one in which sovereignty (hakimiyya) belongs solely to God. He decried all nationalisms as un-Islamic and unnatural divisions of the one true community of Muslims. Consequently, there was not a single Islamic state in the entire world. Every existing society was, therefore, in a state of barbaric ignorance (jahiliyya). Qutb’s solution, outlined in books he wrote and published while still in prison such as the revolutionary manifesto, Milestones, and his Qur’anic commentary, In the Shade of the Qur’an, was the formation of a revolutionary vanguard who would work to overthrow the existing barbarism and reestablish true Islam.

In 1964, Qutb was released from prison at the behest of the Iraqi President, Abdul Salam Arif. He soon became the center of a small group of Islamists that began stockpiling weapons and considered using them against Nasser’s regime. They were, however, soon arrested, and Qutb was hanged at a military prison in 1966.

Hassan al-Hudaybi, the General Guide of the Muslim Brotherhood in the 1950s and 1960s, wrote an influential book entitled Preachers, Not Judges, which criticizes Qutb’s radical diagnosis of Egyptian society without ever mentioning his name. Nonetheless, Qutb’s radical ideas made inroads throughout the Islamic world. Within the Brotherhood, some accepted Qutb’s theories and developed small militant groups. One of these groups, the Egyptian Islamic Jihad, was responsible for the assassination of President Anwar Sadat in 1981. Other Qutbists went on to form terrorist groups, such as Takfir wal Hijra and eventually al-Qaeda. But the rank and file of the Brotherhood, while holding Qutb in high regard, have rejected his most radical ideas. In particular, they have continued to accept the framework of the nation-state system, and their ideology has remained firmly tied to the broader nationalist, anti-imperialist cause.

Calvert lives up to his promise of presenting Qutb with “empathy, not necessarily sympathy.” He gives the reader a real sense of how the world looked to Qutb, but this approach has its dangers. Sometimes, Calvert appears not just to have recapitulated Qutb’s narrative but to have succumbed to it. For instance, he appears to accept Qutb’s declarations of innocence in the plot against Nasser in 1954, writing “it is difficult to judge the validity of the regime’s case against Qutb.” Yet, one does not have to sympathize with Nasser’s brutal government to see that Qutb had declared it illegitimate, called for its destruction, and was in the process of stockpiling weapons. Moreover, Qutb was, by this point, a member of the Muslim Brotherhood, which had already assassinated one Egyptian prime minister and had attempted to assassinate Nasser himself. Later, Calvert even seems to glorify what he describes as Qutb’s “martyrdom.”

If Calvert seems to have misjudged Qutb’s propensity for violence against Nasser, he doesn’t fail to recognize the intensity of his loathing for Jews, although he may explain it away too easily. He argues that Qutb’s anti-Semitism should be understood in the context of the colonial oppression that left Egyptians “aware that their nation’s destiny was in the grip of others—the British, the Americans and the economic elite, many of the latter with roots outside the country, who, directly or indirectly, were connected with the monarchical-parliamentary regime.” He further notes that Qutb believed that “the Jews stand behind an entire range of modern-day calumnies, including Freudian psychology and Marxist socialism,” but he fails to note where Qutb got such ideas. As Jeffrey Herf has shown, Qutb’s book Our Battle with the Jews and other similar works were strongly influenced by wartime Nazi propaganda. That Calvert has chosen to gloss over Qutb’s absorption of some of the worst strains of European anti-Semitism is unfortunate.

With the renewed prominence of the Muslim Brotherhood in post-uprising Egypt, Sayyid Qutb may be more relevant than ever before. Over the past three decades, the Egyptian Brothers have done a good deal to separate themselves from Qutb’s legacy, most recently in their willingness to cooperate with secular groups in the protests at Tahrir Square and afterwards. In fact, the Muslim Brotherhood now finds itself in a position very similar to the one it occupied over half a century ago during the Free Officers Revolution, in which Qutb played a key role. It enjoys widespread support and is aligned with a broad array of political movements. But how long will this last? Now that Mubarak is gone, the Brothers, and Egyptians in general, will have to decide not what they are against, but what they are for. If they refrain from turning to Qutb, Egypt will be much closer to the democracy and freedom that it deserves.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

I’m Still Here

Tuvia Reubner has said he has no homeland except perhaps his poetry. A new book expands that homeland's borders.

Us or Them

It all started with a tweet: “Curious about your whiteness? Come to our meeting.” Edelman was curious.

The Nation of Israel?

The case for an Israeli—not Jewish—republic.

Brother Daniel, Sister Ulitskaya

Ludmila Ulitskaya's fictionalized version of the Brother Daniel case asks us all to turn the other cheek.

ifrane

Everybody knows that Nasser betrayed Qutb,he used him to overthrow the government and then went his own way and neglected the promises he did to Qutb to give Islam a place in the Egyptian constitution and governmental law. Furthermore, it is not strange to have anti-western thoughts, if you lived your youth in a country torn by kolonialism and English supression. This, we must not forget. So to link Qutb to Al Qaeda is disrespectful in my view.