On the Separation of Yeshiva and State

Editor’s note: This essay is part of an exchange with Michael A. Helfand. You can read Helfand’s essay here.

Should the United States keep the separation of church and state that has endured in the country since its founding? Or should we abandon that tradition in favor of a system in which the state funds parochial religious education, as is normal in countries with established state religions?

That’s the real question at issue in Carson v. Makin that the justices will decide in June—not religious liberty. The petitioners want the state of Maine to pay their children’s tuition at the evangelical Christian school they attend because the state pays for secular private education for kids in remote districts where there is no public school. The state says, basically, that it may choose not to fund religious education to protect separation of church and state—the way essentially every school district in the country has done since the invention of public schooling in the nineteenth century.

As a small minority in a mostly Christian country, American Jews have historically believed that robust separation of church and state protects their equality as citizens. The logic isn’t hard to see. Bringing religion into the public sphere and directing taxpayer dollars to religious training and worship tends to make religion more, not less, relevant to citizens’ public standing. Tax dollars raised from Jews (or Muslims, or Hindus, or any other minority) might well end up cross-subsidizing Christian teaching with which Jews might not agree.

Then there are the lessons of history. Jews’ experience with established religions in Europe was, shall we say, fraught. In contrast, the Jewish community in the United States is the freest and safest and best established and most equal to others in two thousand years of diaspora. The idea that this extraordinary equality has nothing to do with America’s separation of church and state is too absurd to be contemplated seriously. Small wonder that all the Jewish Supreme Court justices to have served in the era of church-state jurisprudence have been strongly pro-separation, with no exceptions.

In keeping with this broadly shared view of the value of separation, American Jews have long supported civil society organizations that go to court in defense of it. Americans United for Separation of Church and State was originally called “Protestants and other Americans United for Separation of Church and State,” and those others were mostly Jews. The ACLU, avowedly secular, has always benefitted from Jewish American support. The ADL filed a friend of the court brief in the Maine case saying the Constitution doesn’t require the state to fund evangelical education.

Enter a (relatively) new player in American Jewish legal advocacy: the Orthodox Jewish movement. Its lawyers, including Professor Helfand, take the opposite tack. In case after case, they argue not only that the state may fund religious educational institutions but that it must do so—that failing to fund religious education is a form of religious discrimination that violates the free exercise clause of the First Amendment.

Politically, this divergent position grew from the Orthodox alignment with Protestant evangelicals and conservative Catholics on a wide range of issues, from gay rights to family values to (some) foreign policy. Orthodox Jews tend to be Republicans, and the Republican party today favors state funding of a range of private religious functions.

Financially, Orthodox Jews stand to benefit much more than other Jews by state funding for religious schooling. They are far more likely to send their children to religious Jewish day schools and yeshivas than are Jews who belong to other denominations or no denomination. The same goes for institutions of higher learning. Haredi men are especially likely to attend yeshivas rather than secular universities, yeshivas that can benefit from state money.

Culturally, Orthodox Jews tend to be unworried about being marginalized from mainstream society via increased public salience of religion. Haredi Jews already publicly and proudly distinguish themselves from the mainstream with their distinctive clothes, institutions, and lifestyle. Modern Orthodox Jews tend to be strongly self-identified and frequently experience themselves as accepted (to the extent they want to be) by their coworkers and neighbors.

Conceptually, Orthodox advocates have borrowed the argument made by American Catholics on and off since the 1830s: that the state treats them unequally when it makes them pay taxes for public schools to which they would prefer not to send their children. The modern version of this argument adds, with considerable justification, that the reason states like Maine have never funded sectarian education is that they didn’t want to fund the Catholic Church.

It is certainly true, as I showed two decades ago in Divided By God: America’s Church-State Problem and What We Should Do About It, that the elected officials of the nineteenth century (at the time, Republicans) who pressed hardest for barring state funds to religious schools were anti-Catholic. It is also true that, through much of the nineteenth century, the Catholic Church officially rejected the idea of the liberty of conscience as “deliramentum”—that is to say, a delusional heresy. The deeper, complex truth is that the history of the state-by-state decision not to fund religious education was both a manifestation of anti-Catholicism and, at the same time, an affirmation of the critical importance of separating church and state.

In the Carson case, the Orthodox advocates’ immediate target is a doctrine developed by Chief Justice John Roberts in a 2017 case, Trinity Lutheran Church of Columbia, Inc. v. Comer. The background to the Trinity Lutheran case was a 2003 decision, Locke v. Davey, in which the late chief justice Willian Rehnquist wrote for the court that although states were permitted by the Constitution to fund religious education indirectly, via school vouchers, they were also permitted to decide not to fund religious education if they wanted to protect separation of church and state.

Between 2003 and 2017, conservatives became more aggressive in their pursuit of judicially mandated funding for religion. The Trinity Lutheran case involved state funding for rubber playground surfaces. Roberts wrote the majority opinion, holding that if the state funded any playground resurfacing for private schools, it had to include church preschool playgrounds.

But Roberts, who clerked for Rehnquist, did not want to overturn his old boss’s Locke v. Davey opinion. So he reasoned, talmudically, one might even say, that there was a difference between the state refusing to fund a religious purpose, like religious education, and refusing to fund a religious institution’s secular conduct. The state could protect separation of church and state by not funding religious teaching but could not “discriminate” against religious schools when funding playground resurfacing.

Roberts’s distinction was rejected by Justice Neil Gorsuch, who ridiculed the idea of distinguishing a religious institution’s purpose from its secular undertakings. Echoing Gorsuch, Helfand and others now argue that Judaism itself proves his point: there is no way, they say, to distinguish an Orthodox Jew’s secular conduct from what is religiously demanded of him by halakha.

There are two ways to respond to this claim. The first would be to insist that as a matter of US constitutional law—not of halakha, by which the Supreme Court is not bound—it is actually fairly simple to distinguish religious purpose from secular conduct. To be sure, Moses Maimonides said that everything a Jew does in his life should serve the higher purpose of loving God. But the Supreme Court could defensibly conclude that this sweeping Aristotelian conception of Judaism isn’t required by the Constitution. Torah study is Torah study. Playgrounds are playgrounds. As a matter of constitutional law, we need not say that recess in the yeshiva has a religious purpose.

The other response is simply to concede the limitations of Roberts’s distinction between purpose and conduct while concluding that Locke v. Davey was correct and that states should therefore be allowed to refuse to fund even the secular conduct of religious institutions. If the distinction doesn’t hold water, it shouldn’t follow that the state must fund religious teaching but that the state should be able not to fund playground resurfacing at religious schools. That, in fact, was the tradition in the US from the founding until 2017.

This analysis reveals the far deeper trouble with treating the states’ ongoing refusal to fund religious schools as a form of religious discrimination: if the Orthodox advocates’ view were somehow correct, it would follow that the separation of church and state must itself be a form of religious discrimination. Consider that the state ordinarily may promote cultural or scientific ideas and institutions it holds dear. If the state funds the library and the ballet and the laboratory, then it must be discrimination for it not to fund the yeshiva and the cloister and the school attached to the megachurch. If it pays the salaries of public school teachers, it must be discrimination not to pay rabbis, preachers of the Gospel, nuns, and imams to inculcate their truths.

That is, in fact, what the Orthodox advocates want, alongside their evangelical and Catholic allies: to effectively end the separation of church and state so the government may fund their synagogues and churches and schools and pay the salaries of their respective clergy who teach religious truths.

Their view represents a fantastically transformative account of church-state relations in the US. For it to prevail at the Supreme Court, which seems increasingly like a certainty, would mark an instance of what Nietzsche called the transvaluation of values. Religious liberty, once conceived as inextricably linked with liberal separation of church and state, will have been flipped on its head to serve as a justification for mandatory state support for religion.

Would this, will this, be good for the United States? In my view, the answer is a clear no. Religion has flourished in the United States for centuries without state aid. Even if the government’s role as patron of religion doesn’t end up compromising the independence of religion itself, the extra infusion of state support is wholly unnecessary. What is more, widespread religious education seems unlikely to promote national unity in a time of intense polarization. The Constitution should be interpreted to mandate separation of church and state, not mandate the dissolution of the separation. If the democratic majority prefers not to fund religion, it should certainly not be forced to do so by the courts under a discrimination theory.

Will it be, you should pardon the expression, good for the Jews? Again, my answer is no. Certainly not for the majority of American Jews who want their Jewishness to be irrelevant to their public standing as citizens. And not even, in the long run, for those Orthodox Jews who now believe their interests will be served by state funding for Torah learning.

The Orthodox community has benefited mightily from the work done by earlier generations of mostly non-Orthodox Jews to help create a public culture in the United States that is inclusive with respect to religion. The normalcy associated with Joe Lieberman’s Orthodoxy when he ran for vice president and with Jared and Ivanka Kushner’s Orthodoxy while working in the White House is the product of a separationist political culture, not one in which religion is front and center.

It is perfectly understandable—albeit historically unprecedented—for Orthodox Jews to make common cause with evangelicals and the Catholic Church. Yet it must be remembered that the alliance is contingent on the existence of mutually fulfillable claims to state resources. If zero-sum politics were to enter the picture, Orthodox Jews would immediately be the losers given their numbers relative to Christians in America. And zero-sum religious politics is exactly what many right-wing evangelical Christians believe is their spiritual duty.

People who sincerely attest that there is no salvation outside their preferred true church are not, on the whole, committed to religious equality out of respect for nonbelievers. Some may well be genuine devotees of the doctrine of the freedom of the soul. But a world in which the state funds the teaching that nonbelievers are going to hell is not a world in which the equality of all humans, regardless of religion, is likely to be conventional wisdom for long.

I am as willing as the next diasporic Jew to entertain the theory that the best collective Jewish political strategy is for at least some Jews to be on both sides of every major issue. That way, whoever wins, Jews will have some representation and voice. Through this lens, Orthodox Jewish Republicanism can be seen as a communal hedging strategy. Given that the conservative Supreme Court is poised to change the nature of the separation of church and state in the name of religious liberty, the argument might go, there should be some Jews urging the justices to do just that.

But any such pragmatist view should be able to recognize that some issues are just too important to the equality of Jewish Americans to be left to the divide-and-survive calculus. The separation of church and state is the archetypal example. An America that does not separate church from state will not be a multireligious pluralist utopia. It will be a Christian nation—by virtue of its Christian majority.

The value of Torah learning is beyond rubies. But Jews can and will and do learn Torah in America without the taxpayer footing the bill. It is manifestly much better for American Jews to be equal citizens of a state with no religion than to be second-class citizens in a Christian nation. State funding for yeshiva learning is not worth buying at that price.

Suggested Reading

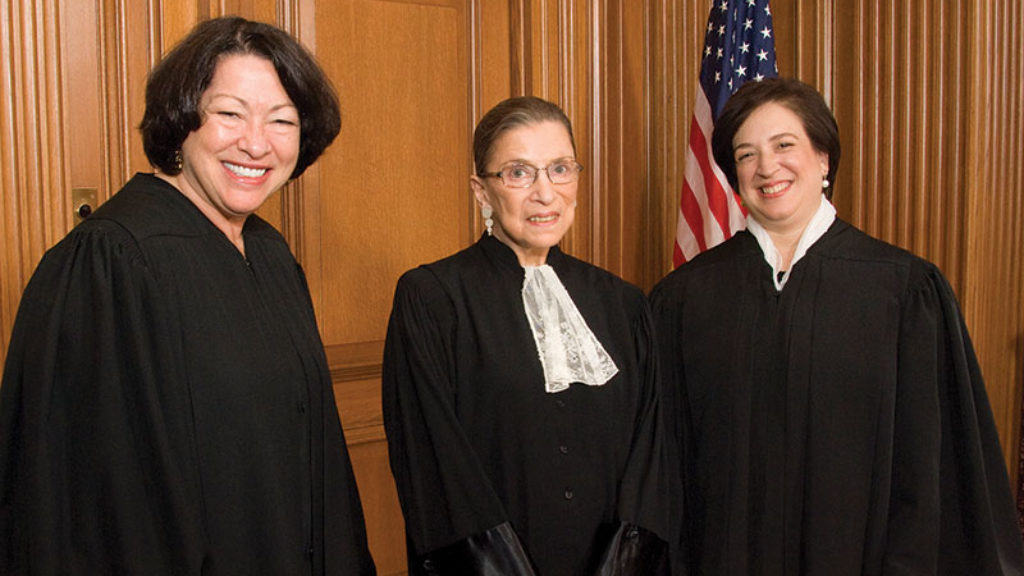

Great Jews in Robes

If Merrick Garland had been successfully confirmed for the seat now occupied by Neil Gorsuch, Jews would have been just one vote shy of constituting a majority on the court.

Why I Defy the Israeli Chief Rabbinate

Everyone knows that the Israeli Chief Rabbinate is often capricious, needlessly adversarial, and hopelessly bureaucratic. Actually, it’s worse than that. It can’t be abolished any time soon, but its power should be radically diminished.

Ireland and the Promised Land

Why isn’t Israel more like America, Jews from that country wonder. In his ambitious new book, Alexander Kaye instructively raises the question of why Israel isn’t even less like the United States.

Culture and Education in the Diaspora

After 1948, Ben-Gurion strongly urged young American Jews to make aliyah. In 1951, Hayim Greenberg, head of the Jewish Agency's Department of Education and Culture, came to Jerusalem to argue for the dignity of Jewish life in the diaspora—in Yiddish.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In