Dusting Off the Old Stories

There is one shelf in the somewhat neglected corner library of my synagogue’s kiddush room that I like to think bears the implied label “Americana,” spelled out in invisible Hebrew letters. Here one finds some of the classic centuries-spanning surveys, such as Howard M. Sachar’s dense and stylishly written A History of the Jews in America, clocking in at a breezy one thousand pages, as well as books I mentally file under “Jews in odd places and times”—that is, in the American context, anywhere west of the Appalachians or anytime before 1880. Carrying titles like Pioneer Jews and Our Southern Landsman, these volumes tell and retell a familiar set of just-so stories of literally path-making Jewish frontiersmen and peddlers-turned-impresarios. Some boast of Jewish contributions to the Confederacy, a point of communal pride back when the conciliatory narratives of the post-Reconstruction era still held sway, now a source of embarrassment. Largely unburdened by footnotes, these midcentury books were meant to showcase Jewish contributions to our early national history—to stake an unimpeachable claim to having long been part of the great American pageant. Despite a plethora of better and deeper books in recent years, these stories remain foundational to what many of us think we know about early American Jewish history.

Take the Revolution. Many of those twentieth-century works celebrated the vastly overstated contributions of Jewish patriots like Haym Salomon, whose brokerage of war bonds and occasional personal loans to founding fathers like James Madison (who acknowledged to an associate, somewhat condescendingly, “the kindness of our little friend”) were later transformed into outrageously exaggerated claims that Salomon was “the financial hero of the Revolution.” It’s a story long grown stale, not least, as historian Adam Jortner writes in A Promised Land, because it bolsters rather than undermines certain age-old canards—specifically, “the mythology of Jews as moneylenders whose cash represents the sum total of their worth as allies.”

Dusting off the old stories, grounding them in better evidence, and adding a great many new ones, Jortner’s book makes the provocative and largely convincing argument that Jews in the early United States, though few in number (there were no more than three thousand across the thirteen colonies), were among both the most eager participants and the prime beneficiaries of the American Revolution.

Though hard numbers are impossible to come by, Jortner contends that most Jews in the colonies had more to gain than lose in joining the incipient rebellion against the Crown. Although royal officials demanded pledges of faith in Christianity from voters and officeholders, the ranks of the Patriot forces were open to colonists of any religion. Jews benefited from the social upheaval of the period, which allowed common people to have a say in public affairs for the first time. “As the patriots took control,” Jortner writes, “those who had been on the outside were now holding the reins of power.” In Savannah, Georgia, Mordecai Sheftall ran the ad hoc revolutionary committee that ended up serving as a provisional government. The royal governor of Georgia dismissed the rebels in his province as “a Parcel of the Lowest People, chiefly Carpenters, Shoemakers, Blacksmiths, etc. with a Jew at their head.”

Jews immediately recognized how good they had it in the United States under the new regime. When the Constitution was ratified in 1788, Richmond’s Jewish community held a banquet to celebrate the occasion. As one of the toasts put it, “May the Israelites throughout the world enjoy the same religious rights and political advantages as their American brethren.” At the grand procession in Philadelphia that summer to cheer the ratification of the new document, Jacob Raphael Cohen, the unofficial rabbi of the city’s Mikveh Israel congregation, marched arm in arm with other clergymen, and a feast at the end of the parade included a table of kosher food. Non-Jewish supporters of the Constitution in New York pushed their own celebration back by a day so as not to conflict with Tisha b’Av.

It is not the case, however, that all American Jews immediately backed the Revolution, were fully welcomed into its ranks, and applied its principles of equality from which they themselves benefited to others. Rather than sweep less pleasant aspects of his story under the rug, Jortner goes out of his way to address such inconvenient truths and fold them into his larger narrative.

Although he celebrates the self-chosen exodus of many Jews from New York as British forces took it over in the summer of 1776, Jortner also notes that many did not flee. At least fifteen New York Jews not only made their peace with living under armed occupation but rejoiced in “loudly announcing their loyalty to the Crown.” Readers may be familiar with the story of Shearith Israel’s hazzan, Gershom Mendes Seixas, carrying the synagogue’s Torah scrolls into exile, first to rural Connecticut and then to Philadelphia. Jortner rightly calls the tale both “heartwarming and uplifting” and “also a little schmaltzy.” Indeed, there’s more to the story:

Shearith Israel was not an empty storefront. The synagogue had two Torahs. One headed to Connecticut, the other stayed in New York: a patriot Torah and a tory Torah. Some Jews chose to struggle on under British occupation.

On one occasion, Seixas himself snuck back into redcoat-patrolled New York to officiate at a Jewish wedding.

For some Jews, life under British occupation was anything but a struggle. Rebecca Franks, from a prominent family in Philadelphia, was the star of the city’s social scene under British rule. Known around town as “the Jewess”—she had a Jewish father but a Christian mother and was said to love ham—Franks was toasted as the belle of every Philadelphia ball. “You can have no idea of the life of continued amusement I live in,” she wrote at just the moment, Jortner observes, when the Continental Army “shivered miles away at Valley Forge.” Franks’s father, a wealthy trader, was tried for treason when the British abandoned Philadelphia and the Americans returned. The celebrated Jewess was expelled.

Then there were the fierce headwinds with which all Jews in the period, even the most devotedly patriotic ones, had to contend. (Jortner insists on describing the bigotry of the time as “anti-Semitism”—a phrase coined a full century after the period in question—but it seems contesting this anachronistic usage may be a losing battle.) Resisting the urge to lapse into the old-style triumphalism, Jortner emphasizes that Jews in the early republic had to constantly fight to keep the gains they secured in the Revolution. There was a perpetual back-and-forth, with years of promise and progress suddenly challenged by a fresh upsurge of prejudice.

In a foreshadowing of the outbursts that accompanied future conflicts, especially the Civil War, the hardships and setbacks of wartime fueled accusations of Jewish perfidy and treason. A letter in a South Carolina newspaper blamed Jews for amassing “ill-got wealth” as well as for “dastardly turning their backs upon the country, when in danger, which gave them bread and protection.” After the war, a pamphleteer in Georgia argued that Jews entered politics only to pursue “their pecuniary interest, the principle of lucre being the life and soul of all their actions.” During the debate over the Constitution, one anti-Federalist opponent warned that if someday there were a Jewish president, “our dear posterity may be ordered to rebuild Jerusalem.” A new state constitution for Pennsylvania ratified in 1776 reaffirmed the colonial requirement that all officeholders take an oath expressing belief in the “divine inspiration” behind both the Old and New Testaments.

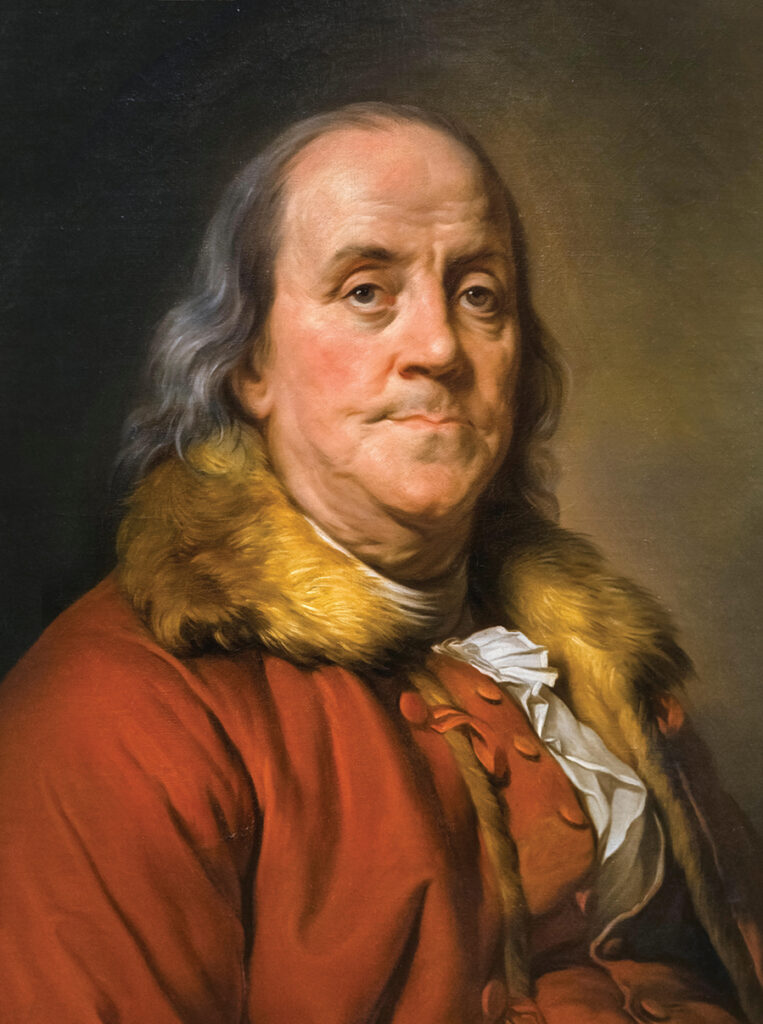

Incidents like these challenge Jortner’s case, but he carefully unpacks and contextualizes them. For example, the Pennsylvania provision was pushed by conservatives like Lutheran theologian Henry Muhlenberg, against the opposition of revolutionaries like Benjamin Franklin (who later recalled his side had been “overpower’d by Numbers”). “It was not an auspicious beginning for Jewish freedom at the dawn of the Revolution,” Jortner concedes, before noting that Muhlenberg possessed less-than-stellar credentials as a patriot and pledged allegiance to the British when they took Philadelphia the following year.

Jews in Philadelphia worked tirelessly, yet always delicately, to overturn the state constitution’s religious restrictions—“a stigma upon their nation and their religion,” as Seixas put it—and finally succeeded in 1790. By then, of course, the new US Constitution had been drafted and adopted, forbidding such requirements at the national level. This episode ends up affirming perhaps the strongest of Jortner’s claims, the one that separates his nuanced narrative from more simplistic treatments: Citizenship was not simply handed to Jews either as compensation for backing the Revolution or in the inevitable unfurling of its stated ideals. Rather, “they fought to make themselves citizens.”

But not necessarily to make everyone a citizen. Jortner is attentive to the long-overdue need to fold slavery back into American Jewish history, while careful at the same time not to let it overwhelm the largely positive story he wants to tell. Echoing the Harvard historian Jane Kamensky, Jortner wishes to highlight how the American Revolution at once “stank of blood and festered with unrealized expectations” and also in “real and concrete ways . . . expanded freedom.”

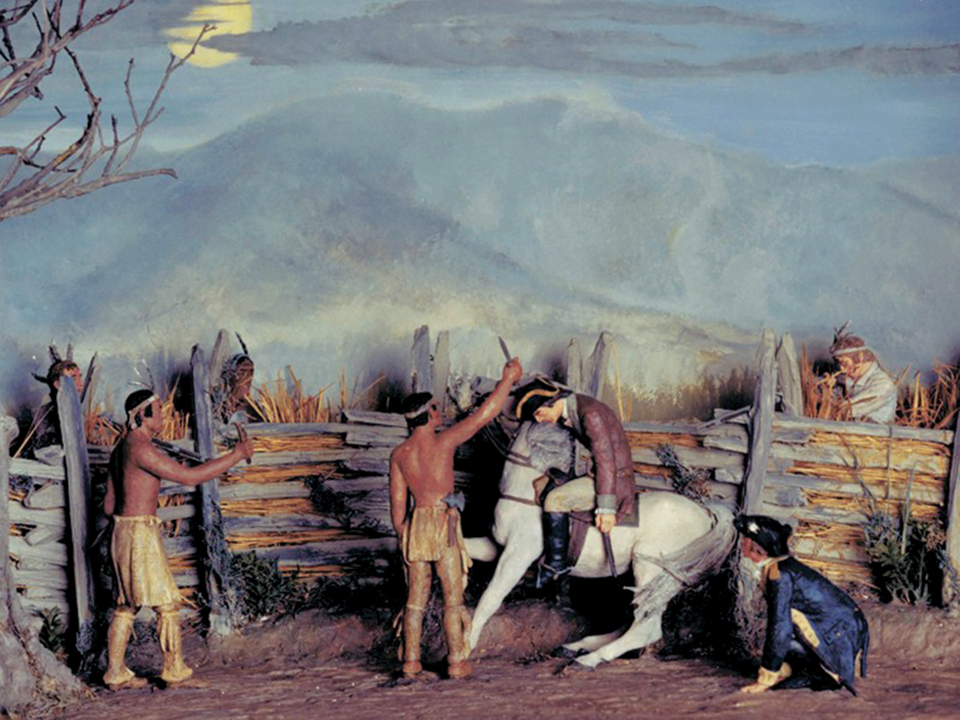

Many of the Jewish patriots whose contributions the book celebrates owned slaves before the Revolution and continued to do so afterward. Jortner is at times careful to note these connections but sometimes misses them entirely. Consider Francis Salvador, the first Jewish patriot to die in battle (he was ambushed and scalped by a party of British-aligned American Indians in July 1776). Salvador has long been a fixture of feel-good accounts of Jewish participation in the Revolution. Jortner describes him as someone who “lived in the South Carolina backcountry”—which he did, in the words of historian Morris U. Schappes, as “the owner of 7000 acres and many slaves.”

Yet just when one begins to suspect Jortner guilty of sequestering his slavery material and avoiding the way in which tragic aspects of American Jewish history are inextricably intertwined with the heroic, he draws out a startling connection between the two. Writing about the patriot leader Mordecai Sheftall’s imprisonment “amongst the drunken soldiers and negroes” after the British captured Savannah, Jortner pointedly wonders “if Sheftall, who was himself a slaveholder, learned anything about the justice of human bondage.”

A rich, absorbing, meticulously researched book, A Promised Land has one persistently frustrating flaw, which is Jortner’s tendency to make grand, sweeping claims that often don’t pan out. His introduction says the story of Jewish patriots “rises in the mountains of New Mexico.” Color me intrigued. Only, nearly thirty pages later, all we get is a brief mention of supposed evidence of crypto-Jewish practices in twentieth-century Santa Fe. Later, he insists on describing Philadelphia’s Mikveh Israel—initially founded in 1740, it was rededicated, with a more democratic constitution, in 1782—as American Jews’ first “national organization” because its wartime members included exiles from British-occupied New York and Charleston. Yet he is unable to cite a single one of them saying anything of the kind, and most of the exiles, as Jortner shows, went back where they had come from after the war. There, they likewise democratized their own synagogues, prompting Jortner to contend that “the American revolution likely had a greater immediate effect on Judaism than on any other religious group in America.” It’s a bold but reasonable interpretation. Why overdo it by adding that, therefore, “Judaism may well have been the first truly national American religion”? What does that mean?

As his narrative leaves the Revolution proper and moves into the pivotal 1780s, Jortner baldly asserts that “Jews and Judaism were front and center as the debate over the federal Constitution stirred the nation.” But all he can summon to support this are a few stray mentions in pamphlets and convention debates. Jews were a negligible topic in the ratification struggle. Why pretend otherwise? “No Jews were elected to the ratifying conventions,” Jortner admits—but people who knew Jews were! Forced to confront the paucity of proof for his claim, the author grants that “Jewish rights were an issue in ratification, but they were certainly not the issue.” Even that overstates things considerably.

In the end, A Promised Land offers not so much a corrective to those tidy tales that fill the midcentury works on the shelf at my shul as it does a rigorous deepening and complicating of the historical argument for Jewish belonging in the United States. Perhaps most pertinently at this moment, Jortner shows how descriptions of the American founding as inherently Christian have no basis in fact and, indeed, were developed only decades later by ideologues with little direct experience of the Revolution. George Washington insisted on using nonsectarian language to describe his conception of God—as a general he credited a seemingly miraculous shift in weather to “Providence or some unaccountable something.” When asked directly, as president, to identify himself as a “disciple of the Lord Jesus Christ,” he instead invoked “the Great Author of the Universe.” Alexander Hamilton successfully argued a New York court case in the 1790s that rejected a bid to exclude a Jewish man’s testimony because of his religion. These and other examples show that the Revolutionary period offers far more support for the idea that the founders intended the new republic to be open to people of all religions, even those who subscribed to none. Thomas Jefferson, ever contradictory, known to have written both positively and negatively about Jews, reflected in a late autobiographical fragment that American protections for religious freedom were meant to include “the Jew and the Gentile, the Christian and Mahometan, the Hindoo, and infidel of every denomination.”

Museum of Kahal Kadosh Beth Elohim.)

More subtly, Jortner’s book challenges twentieth-century Progressive historians who, citing the persistence of class conflict in the early republic, contended that not much changed in America after the Revolution as well as more recent chroniclers who cite constitutional protections for Southern slavery to make the same point. While not discounting those continuities, Jortner sees the gains that Jews consolidated after 1776 as conclusive evidence for what Gordon Wood has called “the radicalism of the American Revolution.” Jews enjoyed liberties in the United States that they had not in British North America—and wouldn’t in England and much of Europe for decades or longer.

Even if religious freedom was not an explicit goal of the world-shifting colonial uprising, it ended up being one outcome of the era’s broader upheaval. “The revolution was not all heroics and noble sacrifices and untrammeled victories,” Jortner writes. “But neither was it all just talk.” The experience of American Jews is ample proof.

Suggested Reading

A Savannah Poet

The Civil War cut short many lives, and in a book that blends the genres of history and memoir, Jason K. Friedman sets out the resurrect the memory of one of those lives.

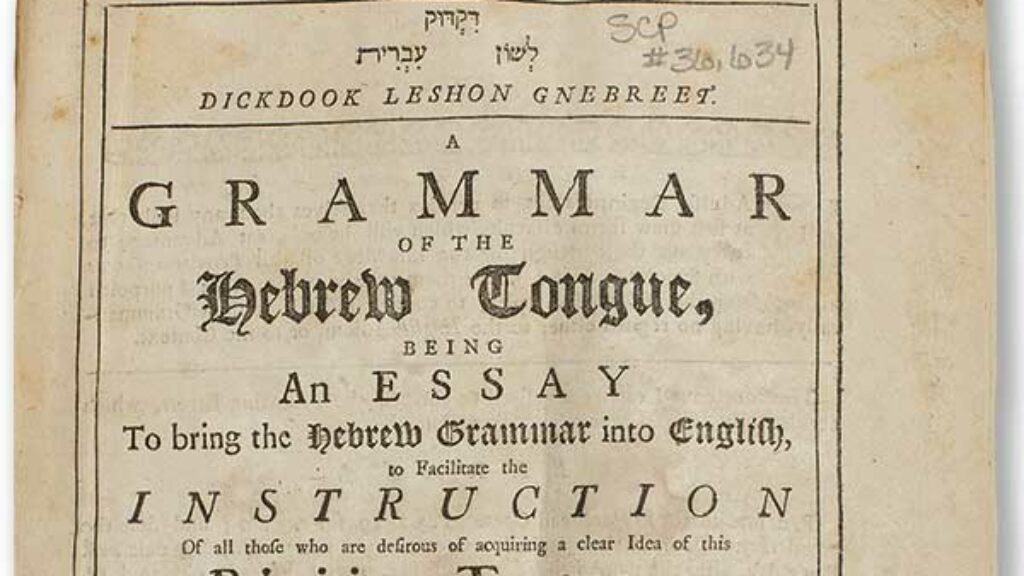

Inventing American Judaism

Unlike the Jews of Venice, whose charter was anxiously renegotiated every decade or so, American Jews participated in civic life, confidently building themselves a future.

Israel on the Hudson

An ambitious, new three-volume work attempts to tell the story of New York's Jews from the days of Peter Stuyvesant to the present.

No Greater Love

The Israeli music scene is bringing together world-class Israeli jazz and classic Sephardic liturgical music. Voilà!: the jazz piyyut.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In